The three special cases: demographic processes in the South Caucasus

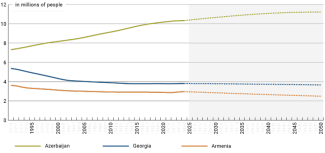

Over the past 35 years, the population of the South Caucasus has increased from approximately 15.7 million to around 17.2 million.[1]This growth is entirely attributable to Azerbaijan, where a relatively high fertility rate persisted until the mid-2010s. The number of residents has declined in the region’s two other states, though for different reasons: in Georgia, primarily due to the outflow of non-Georgian populations and the loss of control over Abkhazia and South Ossetia,[2] (these parastates are not included in Georgian statistics), and in Armenia, owing to emigration and a low fertility rate (see chart 4).

According to World Bank projections, current demographic trends in the South Caucasus are likely to continue over the next quarter-century, though in a more ‘flattened’ form. By 2050, Azerbaijan’s population is expected to grow slightly, while Georgia’s will decrease by a similar margin (Armenia’s decline is projected to be more pronounced). Each of these states thus represents a distinct ‘special’ case, and their particular demographic situations have been shaped largely by recent historical events, especially conflicts. This does not mean, however, that there are no regional trends. The most significant of these is a form of ‘homogenisation’: in all three countries, the share of titular nationalities has risen markedly (this also applies to the Abkhaz in the unrecognised Abkhazia). All states are also experiencing processes typical of wealthier European countries: an increase in the average age of the population as well as in life expectancy and divorce rates, along with a decline in fertility and the number of marriages.

Georgia – the last bastion of a multicultural Caucasus

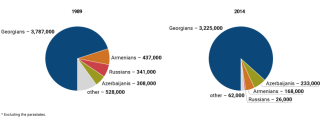

Georgia was – and remains, albeit to a far lesser extent – the most ethnically and religiously diverse country in the region. Shortly before the Soviet Union’s collapse, it had a population of 5.4 million, including 3.8 million ethnic Georgians (70.1%; by comparison, ethnic Armenians made up 93.3% of Armenia’s population, and ethnic Azerbaijanis accounted for 82.7% of Azerbaijan’s). Soviet Georgia was also home to Armenians (437,000; 8.1%), Russians (341,000; 6.3%), Azerbaijanis (308,000; 5.7%), Ossetians (164,000; 3.0%), Greeks (100,000; 1.9%) and the Abkhaz (96,000; 1.8%). Unlike the Ossetians, who were spread across various parts of Georgia, the Abkhaz were concentrated in their own autonomous republic.[3],[4]

In 1989, Abkhazia had a population of 525,000, including 93,300 Abkhaz (17.8%), 239,900 Georgians (45.7%), 76,500 Armenians (14.6%) and 74,900 Russians (14.3%). At the same time, South Ossetia’s population stood at 98,500, consisting mainly of ethnic Ossetians (65,200; 66.2%) and Georgians (28,500; 29%).

As a result of the wars in South Ossetia (1991–1992) and Abkhazia (1992–1993), as well as the Russo-Georgian war (2008), more than 200,000 Georgians left both separatist territories, in most cases relocating to areas of Georgia controlled by the authorities in Tbilisi (while a minority chose emigration). However, some Georgian residents remained in the de parstates. According to local statistics, which are difficult to verify, there were 46,600 Georgians residing in Abkhazia in 2021 (accounting for 17.9% of the population)[5], and 4,000 in South Ossetia in 2015 (7.4%).[6] In both cases, Georgians constituted the second-largest ethnic group after the titular nations. These communities – as with the other populations of the parastates – are not included in official Georgian statistics.[7]

According to the 2024 census, Georgia’s population stands at 3.9 million, although in reality it is likely 100,000–200,000 lower.[8] Regardless of the final figure, over the past 35 years the country’s population has decreased by around 1.5 million (it should be noted that the census did not include the parastates).[9] As of late June 2025, preliminary registry data had not yet provided information on Georgia’s ethnic composition. The last reliable figures in this regard come from the previous census conducted in 2014. At that time, the population was 3.7 million, of which 86.8% were ethnic Georgians (3.2 million). The largest minority groups included Azerbaijanis (233,000; 6.3%), Armenians (168,000; 4.5%), and Russians (26,500; 0.7%).[10]

These figures show that while the country’s population shrank by over 45% between 1989 and 2014, the titular nationality was the least affected – the decline within this group was just under 19%. The share of Azerbaijanis decreased by around one-third, Armenians by more than one and a half times, and Russians by almost thirteen times (excluding the parastates and the later influx of Russian citizens evading mobilisation).[11] People from these ethnic groups typically migrated to their historical homelands – this was especially true of Russians. Despite these trends, Georgia – particularly its major cities, Tbilisi and Batumi – remains multi-ethnic and multicultural, in contrast, for example, to Baku.

Changes in Georgia’s ethnic composition – and likely a slightly reduced share of ethnic Georgians in the overall population – may have been influenced by the abolition of short-term Schengen visas for the country’s citizens in 2017. This is evidenced by the significant growth of Georgian diasporas in EU member states, including Poland, in recent years.

The population increase recorded between 2014 and 2024 is closely linked to the fertility rate, which in recent years has hovered around 2. In 1989 it stood at 2.32, dropped to 1.55 by 2003, and rose again to 2.23 in 2016.[12]

Chart 1. Ethnic composition of Georgia in 1989 and 2014*

Source: author’s own estimates based on census data: the Soviet census of 1989 and the Georgian census of 2014 (a new census was held in Georgia in 2024, but as of August 2025 its full results, including data on ethnic composition, had not been published).

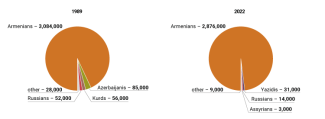

Armenia: a real and a virtual state

Armenia, which was already ethnically homogeneous in 1989, had become virtually mono-ethnic by 2022, when the most recent census was conducted: the share of ethnic Armenians had risen from 93.3% to as much as 98%.[13] This was driven mainly by the outflow of ethnic Azerbaijanis (as well as Kurds) as a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. It is estimated that around 186,000 Azerbaijanis fled to Azerbaijan (according to the 1979 census, over 160,000 members of this ethnic group lived in Armenia, with an upward trend due to high natural growth), together with around 18,000 Muslim Kurds and 4,000 Russians – a total of 208,000 people.[14]

In addition, some of the 330,000 ethnic Armenians who left Azerbaijan relocated to Armenia, while the rest emigrated to Russia or other countries. Those who formally remained in Azerbaijan resided in Nagorno-Karabakh, which was beyond Baku’s control. Following the dissolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh parastate in autumn 2023, its entire population – around 100,000 – fled to Armenia[15], although part of this group later moved on to Russia and Western countries. Nonetheless, the share of Armenians in the country may now be even higher, despite the arrival of roughly 110,000 Russians seeking to avoid mobilisation.[16]

Despite the influx of Armenians from Azerbaijan (and, to a lesser extent, from Georgia), Armenia’s total population has been steadily declining. Between 1989 and 2022 it fell by almost 400,000 (around 10%), from 3.3 to 2.9 million. This trend is the result of both low natural growth (since the mid-1990s, the fertility rate has remained well below 2, dropping to as low as 1.2 in the early 2000s)[17] and emigration. Armenians have been settling abroad for centuries, while maintaining ties with their historical homeland. Together they form a networked ‘virtual Armenia’, which continues to exert influence on Yerevan’s politics. Although the migration balance remains negative,[18] movement between Armenia and the diaspora flows in both directions. After the outbreak of the civil war in Syria, around 12,000 Syrian Armenians arrived in the country.[19] They settled mainly in Yerevan, giving the city a somewhat Middle Eastern character, as they did not speak Russian and often found employment in the catering sector.

Chart 2. Ethnic composition of Armenia in 1989 and 2022

Source: author’s own estimates based on census data: the Soviet census of 1989 and the Armenian census of 2022.

Azerbaijan – the Caucasian hegemon

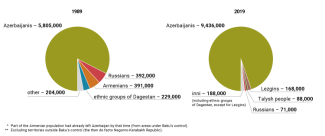

Between 1989 and 2019 (the year of the most recent census), Azerbaijan’s population grew from 7 to 9.9 million (it now stands at 10.2 million)[20] – an increase of nearly 3 million, or over 40%. The number of ethnic Azerbaijanis rose from 5.8 to 9.4 million, while their share of the country’s population increased from 82.7% to 94.8%.[21] This outcome stems primarily from a relatively high natural growth rate, although the long-term trend has been downward. Over the past three decades, the fertility rate has remained close to 2 (in 1989 it stood at 2.8, while in 2025 it is 1.96)[22]. Migration resulting from the conflict with Armenia played a much smaller role, as most displaced people came from Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding areas, meaning they remained within one state. In 1994, the total number of displaced persons in Azerbaijan was around 750,000, roughly 10% of the country’s population at that time.[23] Current statistics do not reflect the outflow of Azerbaijanis from Russia observed in the summer of 2025, triggered by worsening relations between Baku and Moscow. However, it cannot be ruled out that this trend could become more widespread in the coming months.[24]

At present, Azerbaijanis are the largest ethnic group in the South Caucasus, accounting for more than half of the region’s total population – even when Georgia’s breakaway territories are taken into account. This demographic potential underpins Baku’s political ambitions to dominate its neighbours. It seeks to achieve this through its resource policy (oil and natural gas exported via Georgia and Turkey to European states, including EU members, as well as to the Middle East) and through its alliance with Turkey.

Chart 3. Ethnic composition of Azerbaijan in 1989* and 2019**

Source: author’s own estimates based on census data: the Soviet census of 1989 and the Azerbaijani census of 2019.

The region from a bird’s eye view

The logic of demographic processes occurring in each of the three South Caucasus states differs, though there are certain similarities, for example in the depopulation of Georgia and Armenia. In both countries, there was a mass outflow of national minorities. In Georgia, this took place mainly in the early 1990s, linked to the wider crisis and the nationalist policies of its first president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia. The same phenomenon also applies to Azerbaijan, although in this case the Armenian population left territories that Baku had not previously controlled – on a smaller scale in 2020, and on a massive scale in 2023. Labour migration from Azerbaijan (to Turkey or, increasingly rarely, to Russia) is usually temporary. Those who leave permanently are typically dissidents, whose number is estimated at several hundred to a few thousand.

At the regional level, a notable trend is a form of ‘homogenisation’. In every South Caucasus state and de facto entity, the share of the titular population is increasing. In Armenia (and to a lesser extent Azerbaijan), the process has gone so far that the country can already be described as mono-ethnic. Georgia remains the only state with a relatively sizeable proportion of minorities. This is a new phenomenon in historical terms, as South Caucasian states – and particularly the region’s major cities – were typically multi-ethnic and multi-religious. For example, as late as 1989, Armenians made up 10% of Baku’s population, and in the past their share reached as high as 20%. This shift encourages the strengthening of historical narratives centred exclusively on titular nations. While this may bolster national consolidation, it will almost certainly make it harder to integrate minority groups (particularly Azerbaijanis and Armenians in Georgia) and to foster dialogue with neighbouring states.

The South Caucasus is also experiencing processes typical of wealthier European and Western states. Across the region, the average age of the population has risen from 30.1 to 37.8 years over the past three and a half decades, while average life expectancy has increased from 67.4 to 74.4 years. At the same time, the fertility rate has fallen from 2.58 to 1.9.[25] The number of marriages is declining, while the number of divorces is rising.[26] Georgia offers an illustrative case. In 2024, there were 39,500 births (1.8% fewer than in 2023; in 1994 the figure exceeded 57,000) and 44,000 deaths (2.8% more than in 2023). The share of mothers under 25 has fallen, while that of mothers over 40 has increased.[27]

These trends – also evident in the region’s other countries – are linked to lifestyle changes resulting from greater openness to the West (especially in Georgia), rising affluence, and urbanisation. According to the 2024 census, 34% of Georgia’s population lives in Tbilisi, and more than 60% in urban areas overall.[28] Armenia’s urbanisation level is around 64%, with 37% of the country’s population living in Yerevan alone (by comparison, for Poland to have a similar ratio, Warsaw would need to have nearly 14 million inhabitants). In Azerbaijan, the urbanisation rate in 2020 exceeded 56%.

Chart 4. Population of South Caucasus states since 1991, with UN demographic projections

Source: World Population Prospects: The 2024 Revision, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, population.un.org.

An attempt at a forecast

The South Caucasus is currently undergoing a demographic ‘transitional period’, in which declining natural growth is accompanied by a significant increase in life expectancy, with these changes occurring most slowly in Azerbaijan. According to World Bank forecasts, by 2050 Azerbaijan’s population will reach 11.05 million (only slightly more than today), Georgia’s will fall to 3.5 million (a modest decrease), and Armenia’s to 2.6 million (a more pronounced decline).[29] The entire region (excluding Georgia’s breakaway territories) will thus be home to 17.1 million people – roughly the same as today – but two-thirds of them will live in Azerbaijan.

These projections point to a looming demographic crisis in all three countries over the next several decades, creating a need to develop distinct migration strategies. The first signs of this are already visible in the streets of Tbilisi, Yerevan, and – less frequently – Baku, where food delivery workers from more distant Asian countries, such as India and Pakistan, have become a familiar sight.

[1] Excluding Georgia’s de facto entities. When these are taken into account, the figure stands at approximately 17.5 million.

[2] During the Soviet era, South Ossetia was an autonomous oblast. However, in December 1990, Tbilisi abolished its autonomy. Since then, it has been officially designated the ‘Tskhinvali Region’ within the province of Inner Kartli. In practice, however, the historical name is still commonly used – usually to refer to the separatist Republic of South Ossetia.

[3] Abkhazia and Adjara have retained the status of autonomous republics within modern Georgia, a designation they also held during the Soviet era.

[4] The data predating the collapse of the Soviet Union – both here and elsewhere in the text – are drawn from the 1989 census (as cited in: A. Maryański, Przemiany ludnościowe w ZSRR, Warsaw–Kraków 1995, pp. 185–191). For the South Caucasus, this census provides the most reliable point of reference, as it reflects the situation prior to the armed phase of the conflicts in Georgia and Azerbaijan and the mass population movements they entailed. However, by that time, a large-scale exodus of Armenians from Azerbaijan – as well as of Azerbaijanis from Armenia and from the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast within Soviet Azerbaijan – was already under way.

[5] 2021 – Национальный состав наличного населения, State Statistics Committee of the Republic of Abkhazia, 31 December 2023, cgsra.org.

[6] Итоги всеобщей переписи населения Республики Южная Осетия 2015 года, Republic of South Ossetia State Statistics Department, Цхинвал 2016, ugosstat.ru.

[7] In 2021, the population of Abkhazia was reported to be 244,200 – a figure the Georgian authorities consider inflated – of whom 125,400 were ethnic Abkhaz (51.4%). The increase of roughly 32,000 in the Abkhaz population over three decades (more than 30%) can be attributed to a relatively high natural growth rate and the arrival of Abkhaz from abroad, including from former Ottoman territories such as Turkey, Syria, and Jordan. At the same time, Abkhaz who left the republic – particularly for Russia – typically retained their citizenship, maintained ties with Abkhazia and continued to be included in local statistics. In South Ossetia, the number of ethnic Ossetians in 2015 was estimated at 48,100 (89.9% of the de facto state’s total population of 53,500), representing a decline of 17,000 (over 35%) since 1989. This decline was primarily the result of large-scale migration to North Ossetia, which is part of Russia, often for the purpose of family reunification. In such cases, contact with South Ossetia tended to cease almost entirely (see footnotes 5 and 6).

[8] According to the adopted methodology, the census covered not only all Georgian citizens (including those residing abroad) but also foreigners present in the country at the time, regardless of the duration of their stay. This provision therefore also applied to Russians who left their country to avoid mobilisation (see Census 2024, census2024.geostat.ge/en).

[9] Ibidem.

[10] Geostat Releases Final Results of 2014 Census, 28 April 2016, census.ge.

[11] In autumn 2022, 112,000 citizens of the Russian Federation were present in Georgia (‘Migration from Russia 2022-2023: Patterns, Adaptation, Relations’, Social Justice Center, 26 February 2024, socialjustice.org.ge). A similar number – around 100,000 – were reported to be in Armenia at that time (see: А. Агаронян, ‘Точка сохронения’, Новая газета, 21 October 2024, novayagazeta.ru. Far fewer Russians found refuge in Azerbaijan).

[12] Georgia Fertility Rate (1950–2025), Macrotrends LLC, macrotrends.net.

[13] The Main Results of RA Census 2022, Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia, armstat.am/en.

[14] W. Górecki, The Gordian knot of the Caucasus. The conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, OSW, Warsaw 2020, osw.waw.pl.

[15] Idem, ‘Exodus of Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh’, OSW, 3 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[16] ‘Армения назвала число переехавших в 2022 году россиян’, РБК, 16.03.2023, rbc.ru.

[17] Armenia Fertility Rate (1950-2025), Macrotrends LLC, macrotrends.net.

[18] See, for example ‘Около 80% прироста населения Армении – за счет миграции: официальная сводка’, Sputnik, 8 February 2024, am.sputniknews.ru.

[19] ‘Cирийские беженцы в Aрмении’, Deutche Welle, dw.com.

[20] Population of the Republic of Azerbaijan, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, president.az.

[21] The data can be accessed via the website: stat.gov.az.

[22] Azerbaijan Fertility Rate (1950–2025), Macrotrends LLC, macrotrends.net.

[23] А. Юнусов, Миграционные процессы в Азербайджане, Баку 2009, p. 28.

[24] W. Górecki, M. Bartosiewicz, ‘Another stage of the crisis between Baku and Moscow’, OSW, 2 July 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[25] Author’s own estimates based on UN data and statistics from the region’s individual countries.

[26] ‘"Каспий": Государства Южного Кавказа на стадии демографического перехода’, Oxu.Az, 22 June 2024.

[27] ‘В 2024 году в Грузии снова снизилась рождаемость: прирост населения остается отрицательным’, Новости Грузии, 28 March 2025, newsgeorgia.ge.

[28] ‘Уровень урбанизации в Грузии: в городах живет более 60% населения’, Новости Грузии, 25 June 2025, newsgeorgia.ge.

[29] Population, databank.worldbank.org.