The NB8 group and other formats of security cooperation in the Baltic Sea region

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO, cooperation between the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) and the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) within the Nordic-Baltic Eight (NB8) has gained new momentum. Their growing alignment in recent years has been determined by shared interests in supporting Ukraine, imposing sanctions on Russia, strengthening regional security, enhancing energy cooperation, and shaping Eastern policy. Simultaneously, some differences remain in the field of defence, arising from NATO’s regional plans and the Nordic states’ focus on collaboration within their own formats, such as the Nordic Council and NORDEFCO.

The NB8 is likely to remain an exclusive format comprising the Nordic Five and the Baltic Three, bound by a shared self-perception as small countries and a desire to develop a joint Nordic-Baltic ‘brand’. Consequenly, the group has shown little interest in permanently opening itself to other countries. Poland can develop its relations with the Nordic-Baltic states by deepening bilateral ties, expanding military cooperation within NATO, and revitalising collaboration within the Council of the Baltic Sea States, in the NB8+PL format and in an expanded Bucharest Nine group that includes the Nordic countries.

Common ground within the NB8

Since 1990, the NB8 has evolved from a mechanism used by the Nordic countries to support the Euro-Atlantic integration of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia into a platform for coordinating actions and advancing shared interests, particularly in the areas of foreign and security policy.[1] The format is well-suited to small, like-minded countries in the region, enabling them to present a unified position on key issues.

Cooperation within the NB8 format intensified following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Over the past three years, Nordic-Baltic consultations have focused on issues such as supporting Ukraine and Moldova, tightening sanctions against Russia and its so-called shadow fleet, strengthening NATO’s north-eastern flank, countering hybrid operations, increasing resilience to non-military threats, expanding energy cooperation (the Nordic and Baltic states are interconnected through telecommunications and power cables as well as a pipeline) and coordinating actions towards Belarus and Georgia. The NB8 countries have also committed to jointly equipping and training a Ukrainian brigade.

The NB8 format currently includes summits of heads of government, meetings of foreign and defence ministers, state secretaries, and MPs, as well as joint visits to third countries. Each year, a different capital chairs the Nordic-Baltic cooperation; Copenhagen holds the presidency in 2025. The NB8 countries have also issued joint statements at the UN General Assembly and the UN Human Rights Council. Within this format, foreign ministers have visited Ukraine and Moldova. Consultations have also covered developments in the Middle East and the Indo-Pacific, the most notable example being a joint visit by NB8 foreign ministers to New Delhi in February 2024.[2] The NB8 has also engaged in ad hoc cooperation with other countries and groupings, including Poland, Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The process of planning such meetings often reflects the preferences of the presiding capital. In 2024, Sweden, which acted in this capacity and was keen to deepen security cooperation with Poland, invited the Polish foreign minister and prime minister to the NB8’s meetings.[3] Last April, the group held its first meeting with representatives of the Weimar Triangle at foreign minister level. Until 2021, annual meetings were also held between the Nordic-Baltic Eight and the Visegrad Group (NB8+V4).

Nordic-Baltic cooperation in the field of defence has been developing primarily on a bilateral basis and within NATO. Latvia and Denmark jointly operate the Multinational Division North (MND N) headquarters, which reports to the Multinational Corps Northeast (MNC NE) headquarters in Szczecin. MND N is responsible for NATO’s Forward Land Forces deployed in Latvia, including rotating Danish and Swedish battalions.[4] Estonia and Finland, for their part, have cooperated particularly in the maritime domain of the Gulf of Finland, focusing on the military dimension and the protection of critical underwater infrastructure.[5] Nordic companies have also been involved in the modernisation of the Baltic states’ armed forces. Major contracts include deliveries of Norwegian NASAMS ground-based air defence systems to Lithuania and Finnish Patria 6×6 armoured personnel carriers, assembled in Valmiera, Latvia, for the Latvian land forces. Sweden’s Saab is a key supplier to the Baltic states’ land forces, providing anti-tank grenade launchers and very short-range mobile air defence systems.[6]

The Nordic-Baltic protocol of divergences

The NB8’s united stance on Russia and the need to strengthen deterrence took shape only after February 2022, as the Nordic countries adopted the security assessment of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Previously, even in the face of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its growing aggressiveness, the Nordic and Baltic states lacked a unified position. Denmark had long dismissed the possibility of a Russian attack on the Baltic states, focusing on military operations outside Europe. Sweden was slow to rebuild its military capabilities and remained outside NATO. Militarily non-aligned Finland called for confidence-building measures with Russia and maintained extensive political and economic ties with it, particularly in energy and trade. All the Nordic countries also sought constructive cooperation with Russia within the Arctic Council.

Although the era of Nordic-Baltic divergence on security is now a thing of the past,[7] the Nordic countries continue to prioritise intra-Nordic defence cooperation within NORDEFCO. Following the accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO, Nordic defence cooperation is expected to evolve into a militarily integrated, regional pillar of the Alliance within its defence planning for Northern Europe.[8] This includes measures such as developing the capacity to carry out joint operations, enhancing host nation support and military mobility, and strengthening interoperability through joint exercises and coordinated procurement of armament and military equipment. In particular, large-scale advanced Arctic Challenge air force exercises have become the hallmark of Nordic military cooperation. Finland and Sweden have actively sought inclusion in NATO’s regional defence plan for Northern Europe, which already covers the other Nordic countries.[9] The NATO Joint Force Command (JFC) in Norfolk, USA, will be responsible for implementing the plan. Currently, both new member states fall under JFC Brunssum in the Netherlands – alongside Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Germany – but they have already received approval from the NATO Military Committee to be reassigned to the command in Norfolk. A combined air operations centre for the Nordic region and the High North will be established in Norway, while Finland will host NATO’s multi-corps land component command under JFC Norfolk, based on the Finnish Army Command in Mikkeli.

The boundary between the assigned areas of operations of JFC Norfolk and JFC Brunssum will run across the Baltic Sea. NATO’s task will be to integrate the defence plans for the northern and south-eastern parts of the region within a single operational theatre.[10] The Baltic states, particularly Estonia, have occasionally voiced their concerns over Finland and Sweden’s efforts to shift their position within NATO’s command structure, regarding it as a move that could compartmentalise the region, diminish Nordic engagement in their defence, and reinforce inward-looking tendencies among the Nordic countries. Therefore, the Nordic and Baltic states are discussing how to deepen cooperation within NATO’s Defence Planning Process (NDPP) and in the area of integrated air and missile defence.[11]

A regional crucible of cooperation

NB8 is one of many platforms for cooperation in the Baltic Sea region, where several overlapping political-military formats are employed. Among these is the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF), which comprises the United Kingdom, the Nordic and Baltic states, and the Netherlands. Established in 2014, the JEF was designed as a multi-domain rapid reaction force of like-minded nations, capable of deploying up to 10,000 troops. Although originally intended for crisis response operations beyond Europe, today its geographical centre of gravity lies in the Nordic and Baltic region, the North Atlantic, and the Arctic. The JEF has conducted regular military exercises in the Baltic Sea area.[12] Its operational response mechanism was first activated in November 2023, following damage to the Finnish-Estonian Balticconnector gas pipeline. The JEF countries have also expressed interest in expanding their cooperation with Ukraine; in May, they extended an invitation to Kyiv to form an ‘enhanced partnership’ with the JEF.[13]

The United Kingdom also leads the Northern Group, launched in 2010 as a forum for consultations among the defence ministers and chiefs of staff of the UK, the Nordic and Baltic states, the Netherlands, Germany, and Poland, focused on security issues in Northern Europe, including the Baltic Sea region.[14] These meetings also serve to coordinate positions within NATO. Copenhagen hosted the most recent gathering in November 2024, which was attended by Ukraine’s Minister of Defence and Minister of Strategic Industries. The discussions focused primarily on continued military support for Ukraine and cooperation with its defence industry.[15]

Some countries in the region – namely Poland and the Baltic states – also participate in the Bucharest Nine (B9), a forum for consultations between the leaders of NATO’s eastern flank ahead of the Alliance’s summits. In June 2024, the Prime Minister of Sweden and the President of Finland attended a B9 meeting for the first time. Owing to the positions of Hungary, Slovakia and, to some extent, Bulgaria on Russia and Ukraine, the security interests of the other B9 members are now more closely aligned with those of Stockholm and Helsinki than with Budapest and Bratislava. This raises questions about the future of the format.[16] With parliamentary elections approaching in the Czech Republic, the convergence of interests among the B9 members may continue to erode.

The Council of the Baltic Sea States (CBSS) is the only regional forum that includes all countries except Russia (the European Union is also a member), with foreign ministers playing a leading role in its activities. Russia withdrew from the organisation in May 2022, following its suspension by the Council in March that year. To date, the CBSS has focused on cultural and educational cooperation, ‘soft’ security issues – such as combating human trafficking – and sustainable development. Its permanent secretariat is based in Stockholm and operates on an annual budget of €2.5 million. It supports activities of CBSS working groups and manages more than a dozen projects. The Council’s agenda is set by a rotating one-year presidency held by successive member states. On 1 July this year, Poland is due to assume the CBSS presidency from Estonia.

Prospects for future cooperation in the Baltic Sea region

Nordic-Baltic cooperation is set to deepen further in the coming years. In all likelihood, the NB8 will increasingly function as a political ‘consortium’ of small countries working collaboratively to advance their interests and promote a distinct regional ‘brand’ through joint action, primarily in foreign policy, within international organisations, but also in interactions with major global actors. Relations with the United States offer a clear example: on the one hand, the NB8’s unified voice could serve as a useful instrument for persuading the White House to maintain US military presence on NATO’s north-eastern flank. On the other hand, the NB8 has offered Denmark a diplomatic channel of support in response to US claims concerning Greenland. At a time of intensive consultations on European security and the war in Ukraine, the NB8 format may increasingly serve as a ticket to the European decision-making table. One such example was the Paris summit of 17 February, where the Nordic and Baltic states were represented by Danish Prime Minister, Mette Frederiksen, owing to Denmark’s current presidency of the NB8. However, the group is unlikely to expand to include new members such as Poland, which is regarded as a medium-sized country whose inclusion could disrupt the group’s internal dynamics.

The CBSS, which is seeking a renewed purpose amid the war in Ukraine and the shifting security environment, may in future assume a greater role in regional cooperation to counter Russian hybrid activity, especially as it connects the Nordic and Baltic states with larger actors – Poland and Germany. The organisation could help strengthen cooperation and promote an integrated approach to addressing hybrid threats in the Baltic Sea region; however, this would require reformatting its current activities. Such a shift was proposed in a report on its future that was published on 16 May.[17] Its authors advocate transforming the CBSS into a “strategic forum for regional security dialogue” (which could function as a group of influence within the EU and NATO) and “first-response political grouping in the event of major regional security incidents”. In operational terms, it could evolve into a coordination body for countering Russian hybrid activity (see Appendix 1). In a declaration issued on 16 May, the Council’s foreign ministers endorsed the ’spirit of the report’, acknowledging the need to reform the organisation through enhanced security dialogue and cooperation.[18] A memorandum signed the same day by the ministers and the EU representative on the protection of critical underwater infrastructure in the Baltic Sea focuses on countering Russia’s ‘shadow fleet’ and enhancing the security of key infrastructural assets in the region (see Appendix 2).[19] Consequently, upcoming Poland’s presidency of the CBSS faces the task of initiating the organisation’s gradual transformation.

Regardless of the shape of the future participation of Hungary and Slovakia, the Bucharest Nine (B9) – which since 2015 has coordinated the positions of eastern flank countries ahead of NATO summits – may be broadened to include the Nordic dimension. On 27 May, Vilnius hosted a meeting of transport ministers from the B9 and Nordic (N5) countries, attended by EU and NATO officials. The discussions focused on dual-use critical infrastructure projects, cooperation in military mobility, and resilience to hybrid threats – including GPS signal jamming. The first B9 summit with the participation of all the Nordic countries at the level of heads of state and government is scheduled to take place in Vilnius on 2 June.

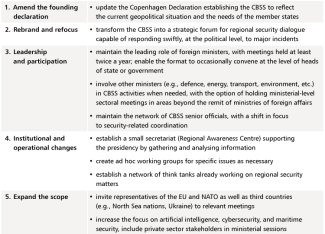

Appendix 1. Selected recommendations from the Ilves-Landsbergis report on the future of the CBSS

Source: The Future of the Council of the Baltic Sea StatesThe Future of the Council of the Baltic Sea States, op. cit.

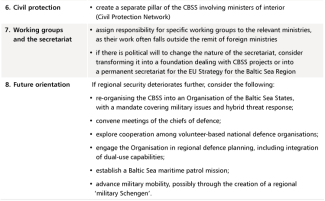

Appendix 2. Key Provisions of the Memorandum on the Protection of Critical Undersea Infrastructure between Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Sweden, and the European Union

Source: Memorandum of understanding the protection of critical undersea infrastructure in the Baltic SeaThe Future of the Council of the Baltic Sea States, op. cit.

[1] D. Szacawa, ‘Poland’s Northern Policy and Nordic-Baltic Cooperation’, IEŚ Commentaries, no. 1255, 19 December 2024, ies.lublin.pl.

[2] ‘The NB8 visit to India focuses on cooperation and trust’, Swedish Prime Minister’s Office, 24 February 2024, government.se.

[3] ‘Nordic-Baltic Summit and new partnership with Poland’, Swedish Prime Minister’s Office, 29 November 2024, government.se.

[4] As part of NATO’s forces in the Baltic states, a Norwegian company has also operated in Lithuania. J. Tarociński, J. Gotkowska, ‘NATO brigades in the Baltic states: new chapters in the long march toward deployment’, OSW, 23 October 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[5] ‘Finland and Estonia to intensify cooperation in protecting underwater energy transmission connections’, The Finnish Government, 27 September 2024, valtioneuvosto.fi.

[6] B. Chmielewski, J. Tarociński, ‘On the warpath: the development and modernisation of the Baltic states’ armed forces’, OSW Commentary, no. 594, 10 May 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[7] Although the Nordic countries, together with the United States and Canada, have been gradually resuming cooperation with Russia within the Arctic Council.

[8] J. Tarociński, J. Gotkowska, ‘Nordic countries: a common vision for the development of defence cooperation’, OSW, 8 May 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[9] K. Friis, ‘Reviving Nordic Security and Defense Cooperation’, Carnegie Europe, 2 October 2024, carnegieendowment.org.

[10] H. Kalm, ‘NATO’s Path to Securing Undersea Infrastructure in the Baltic Sea’, Carnegie Europe, 29 May 2024, carnegieendowment.org; J. Linnainmäki et al., ‘NATO’s new northern direction: The evolving role of the alliance in Europe’s north’, FIIA, April 2024, fiia.fi, pp. 38–40.

[11] ‘Jens Stoltenberg to write report on Nordic-Baltic security and defence cooperation’, Swedish Prime Minister’s Office, 15 January 2025, government.se.

[12] E. Arnold, The Joint Expeditionary Force and its Contribution to European Security, RUSI, 9 December 2024, rusi.org.

[13] This could include Ukraine’s participation in the JEF’s military exercises and meetings, more advanced training support for the Armed Forces of Ukraine, intensified mutual exchange of knowledge on the modern warfare and technological innovations, as well as preparations for Ukraine’s involvement in the JEF’s future activities. The Joint Expeditionary Force Leaders’ Summit Joint press statement, The Government of Norway, 9 May 2025, regjeringen.no.

[14] J. Gotkowska, P. Szymański, ‘Spotkanie Grupy Północnej w Helsinkach’, OSW, 15 November 2017, osw.waw.pl.

[15] ‘Declaration from the Defence Ministers of Northern Group’, The Ministry of Defence of Sweden, 21 November 2024, government.se.

[16] A. Kotseva, K. Nikolov, ‘Bulgarian president blocks common Bucharest Nine position on Ukraine’, Euractiv, 12 June 2024, euractiv.com.

[17] In January, the Estonian CBSS presidency entrusted drafting the report to former Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves and former Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis. The need for such a report had already been identified in 2024 during Finland’s presidency. The report was produced with the support of the Estonian think tank ICDS; it was funded by the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. T.H. Ilves, G. Landsbergis, The Future of the Council of the Baltic Sea States, ICDS, May 2025, icds.ee.

[18] 2025 Vihula Declaration, The Council of the Baltic Sea States, 16 May 2025, cbss.org.

[19] Memorandum of understanding the protection of critical undersea infrastructure in the Baltic Sea, The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania, 16 May 2025, urm.lt.