To už se nevrátí

I. Czechoslovakia – a state that fulfilled its historical mission

1. Czechs and Slovaks on the eve of the First World War

2. The background and reasons for establishing a common state

4. Unifying and dividing elements

5. The first and second dissolution of Czechoslovakia

1. Evolution of political relations

2. The most recent political crisis

3. Not only Babiš – Slovaks in Czech politics and Czechs in Slovak politics

5. Interpersonal relations and culture

Conclusion: a model divorce and close, though no longer strategic, relations

Introduction

The Czechs and the Slovaks are often perceived in Poland – and consequently in debates on Central Europe – as a pair of nations that have been linked ‘since time immemorial’. This perspective overlooks the fact that Czechoslovakia, now slowly fading from memory, was, in the context of the past millennium, a relatively short-lived entity. Established in autumn 1918, it lasted only 20 years in its initial democratic form. Following the Second World War, most of the more than 40 years of Czech–Slovak coexistence unfolded under the period of real socialism (1948–1989), preceded by only a few years of illusory hopes for a return to democratic rule. The opening of public debate in 1989 and the launch of a joint systemic transformation soon led to the Velvet Divorce.

Even under the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, the two nations belonged to different administrative spheres: the Czechs, alongside Galicia (with Kraków and Lviv), were part of the ‘imperial’ Austrian-controlled Cisleithania,[1] while the Slovaks came under the ‘royal’ Hungarian-administered Transleithania. This division created differences not only in political traditions but also in legal systems. As the newly formed Czechoslovakia largely retained pre-existing legal frameworks, Catholic citizens discovered, for instance, that divorce was legally permitted in the Slovak part of the country (a legacy of Hungarian law), but not in the Czech part, where the Austrian Civil Code of 1811 still applied. Such discrepancies had to be harmonised – in the case of divorce, this was achieved to a large extent as early as 1919.

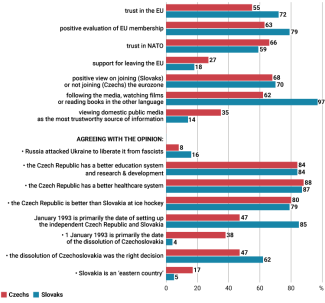

Legal disparities were compounded by socio-economic differences: within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the territory of today’s Czech Republic was far more industrialised, whereas Slovakia remained predominantly agricultural. After 1918, the Czech elites adopted a strongly anti-clerical stance, which under communism provided fertile ground for more effective efforts at promoting atheism. Over time, this deepened the contrast with Slovaks, who to this day display a markedly higher level of religious practice and attachment to the Catholic Church (although a significant part of their elite was Lutheran). These differences widened following the dissolution of Czechoslovakia. Slovakia remains the only Visegrád Group (V4) country to have adopted the euro, and in 2024 its citizens celebrated the 15th anniversary of using the common European currency. The distinct historical experiences of the two societies also shape their differing attitudes towards Russia.

At the same time, the two countries and nations remain bound by enduring cultural and linguistic closeness, reinforced by a significant number of mixed families and migrants from the other state – though this relationship is marked by a notable asymmetry, owing to the Czech Republic’s considerably stronger appeal. This closeness is further deepened by student exchanges, a partially shared readership market, and the cross-border activity of businesses, journalists, experts, and popular cultural figures. The relatively peaceful dissolution of Czechoslovakia facilitated such interaction, as it left neither side with traumatic experiences to process or a desire for revisionist claims.

Moreover, the absence of public consultation in the decision to divide the Czechoslovak state, together with the widespread surprise that accompanied this development, has contributed to the enduring image of a country divided not by mutual animosity but by the political ambitions of individual leaders. Yet, as this analysis has shown, claims of harmonious coexistence between the two nations did not always reflect reality. Even today, some artists and journalists write of a country taken from them against the will of the majority – or rather two majorities – since a truly unified Czechoslovak society never came into being.

These factors have shaped the perception of ‘above-standard’ relations between the two states, including in the political sphere. Their successive leaders have upheld this image by making the other country the destination of their first foreign visit, rarely engaging in open criticism, and frequently coordinating positions on European policy. This cooperation has not always been smooth, and especially in Prague, debate about Slovakia often includes concerns over political developments – particularly since Robert Fico’s left-nationalist government came to power. There is also occasional ‘envy’ of certain Slovak political figures, most recently of former President Zuzana Čaputová, who from 2019 to 2023 stood in sharp contrast to her Czech counterpart, Miloš Zeman. At times, a sense of paternalistic sympathy arises in response to the actions of the ruling camp in Bratislava. Nevertheless, media interest in the neighbouring country remains markedly higher than in most other bilateral relationships.

Understanding the unique bond between the Czech Republic and Slovakia – and the constraints that accompany it – can help in accurately interpreting the dynamics of broader regional coordination. This is all the more important, given that one of the largest armed conflicts since the Second World War is taking place just beyond the eastern borders of Poland and Slovakia. Hungary’s divergent position on the war has, in effect, led to a collapse of political cooperation within the Visegrád Group. These divisions within the V4 on such a crucial geopolitical issue were further deepened by the change of government in Slovakia following the autumn 2023 elections. The rhetoric of Robert Fico’s cabinet regarding the war even led to the cancellation of Czech–Slovak intergovernmental consultations planned for spring 2024. As a result, relations between Prague and Bratislava have fallen to one of their lowest levels since 1993.

This study consists of two main parts, focusing respectively on the shared state and on contemporary Czech–Slovak relations following its dissolution. The first part explores the origins and character of Czechoslovakia, outlining both the elements that supported harmonious coexistence between its nations and the factors that created division. This section also includes a chapter analysing the country’s two dissolutions. The second part examines the evolution of political relations after the Velvet Divorce, with particular attention to interactions between the two governments in recent years. The following chapters investigate economic ties between the Czech Republic and Slovakia, as well as relations among their citizens and within the broader spheres of culture and education. The analysis covers basic demographic data and includes sections on mixed families and complex identities, mutual perceptions, student exchanges, and the intermingling of media and sport. The entire work is supplemented with numerous text boxes that provide deeper insight into selected issues.

Theses

- The exceptional nature of political relations between the Czech Republic and Slovakia is reflected in the disproportionately high level of mutual interest and the precedence given to visits by leading political figures. This stems from the legacy of their former shared state, linguistic kinship, and strong interpersonal ties. The foundation of close Czech–Slovak political relations over the past three decades has been the orderly and peaceful completion of the dissolution of their shared state. The Velvet Divorce was possible because the Czechs – as the larger partner – chose not to forcibly retain the smaller Slovakia. Moreover, the border between them was not a source of dispute, and their shared history is not burdened by armed conflict.

- Despite their overall closeness, Czech–Slovak relations have not always been without difficulties. Since 1993, there have been two periods of particular tension. The first lasted from the dissolution of Czechoslovakia until 1998, when the term of the Vladimír Mečiar’s cabinet in Bratislava came to an end. His administration pushed the country into international isolation, a trend compounded by authoritarian tendencies and numerous domestic political scandals. This situation significantly affected relations with Slovakia’s western neighbour.

- The most serious crisis in bilateral relations in recent years occurred in March 2024, when the Czech government, led by Prime Minister Petr Fiala, cancelled the intergovernmental consultations – a tradition partly initiated by his Slovak counterpart, Robert Fico. The Czech side cited differences in perspectives on key foreign policy issues. Czech–Slovak relations have been significantly affected by the diverging outlooks of the centre-right government in Prague and the left-nationalist bloc that has held power in Bratislava since autumn 2023, particularly regarding support for Ukraine and the rhetoric surrounding it. These tensions are further compounded by differences in political culture (with Czech politics being more moderate) and public opinion (with Slovak society tending to be more pro-Russian), which may hinder rapprochement even after the anticipated change of government in Prague in autumn 2025. The suspension of consultations is not merely a symbolic manifestation of the crisis – it also generates a range of practical problems. These frictions have highlighted the mistake of failing to establish various forms of sectoral cooperation. For example, the Czech Republic and Slovakia lack institutionalised cross-border collaboration, and without political impetus – especially following the cancellation of intergovernmental consultations – it is difficult to advance progress on numerous practical matters.

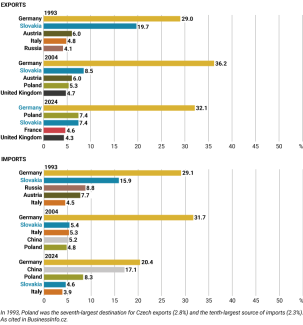

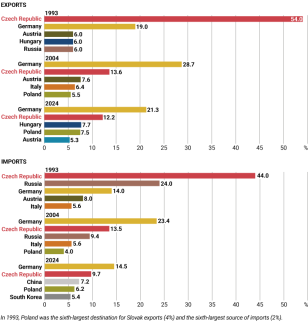

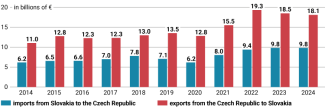

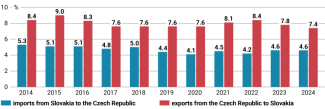

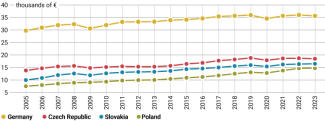

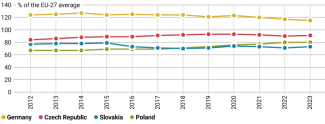

- Asymmetry is a key characteristic of Czech–Slovak relations at various levels. In economic terms, this refers to a disparity in capacity and wealth, which makes the Czech Republic more appealing to Slovaks seeking employment and enables Czech companies to cut costs by operating in their neighbour’s territory. In 2023, real GDP per capita in the Czech Republic was 12% higher. However, Slovakia has managed to narrow the gap from 38.5% in 2005, and its labour productivity – the highest in the Visegrád Group – offers promising prospects for convergence with the Czech Republic. Trade between the two countries continues to grow in absolute terms and remains significant, particularly given the size of their economies. Nonetheless, since the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, they have become less important trading partners in relative terms. This is the result of gradual trade diversification. Between 1993 and 2024, Slovakia’s share in Czech imports and exports dropped by 11–12 percentage points to 5–8%, while the Czech share in Slovak imports and exports fell by 34 and 42 percentage points, to 10 and 12% respectively. Since 1993, economic ties with Germany have become especially important for Prague.

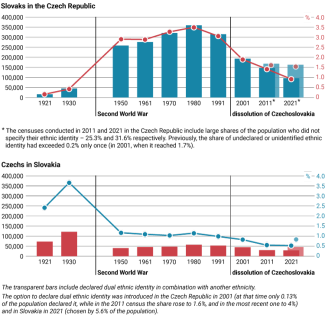

- In terms of people-to-people dynamics, inequalities concern not only the intensity of migration but also the potential for cultural influence. The Czech Republic exerts significantly greater pull, which is why the number of Slovaks moving there clearly exceeds movement in the opposite direction. Many remain in the Czech Republic after completing their studies – a result of generally higher university standards, favourable admission rules, and an overall better standard of living. By contrast, Czechs living in Slovakia are on average significantly older, and their population has been gradually declining since the dissolution of Czechoslovakia. As a result, around 160,000 Slovaks live in the Czech Republic – three and a half times more than the number of Czechs in Slovakia. Although survey data show that the two nations still instinctively evoke positive associations with each other, the passing of generations who remember the shared state inevitably causes interpersonal relations gradually to lose their exceptional character.

- Czech–Slovak relations would probably not have been as intensive across so many areas, nor as positive for most of the period since their separation, without the legacy of Czechoslovakia. Paradoxically, the smooth division of the country also strengthened their ties, as it helped avoid the potentially destructive effects of a protracted disintegration of their shared statehood. In practice, that disintegration had already begun in mid-1992.

- In 1918, the unification of the two nations was primarily influenced by political and ethno-linguistic factors. Politically, the Czechs sought to strengthen their position vis-à-vis the German minority, while the Slovaks aimed to counterbalance the Hungarian minority and to secure protection against potential revisionist ambitions from Berlin (or Vienna) and Budapest. Centrifugal tendencies tended to intensify whenever the state failed to fulfil this protective role or when there were no perceived threats that could justify its existence as a safeguard. Such a situation arose in autumn 1938, when Prague yielded to the Munich dictate and Slovakia lost its southern territories to Budapest. In contrast, in the early 1990s, the absence of any perceived threat from Germany reduced Czech motivation to secure a stronger position within a larger state and even gave rise to concerns about becoming entangled in Slovak–Hungarian disputes.

- Despite their cultural closeness, Czechs and Slovaks have been and remain distinct nations. The assumption held by some proponents of Czechoslovakism – that years of living in a shared state would create a national monolith – proved to be misguided. At the time of Czechoslovakia’s founding, Slovaks were already almost fully formed as a national community, and sharing a state with the Czechs enabled them to complete this process. This union offered the Slovaks, who lacked a tradition of their own statehood, the opportunity to gain greater agency than would have been possible had they remained linked to Hungary. Among Slovaks, there was a discernible and natural drive – characteristic of every nation – to expand their role in governance and, over time, to establish a state of their own. These ambitions, and particularly the absence of autonomy for Slovakia as promised in the so-called Pittsburgh Agreement of spring 1918, arose as an issue almost from the outset of their coexistence. Efforts to forge even a secondary Czechoslovak identity were hindered by factors such as the 1938 decision to forgo war against Germany – a conflict that might have created a bond through shared sacrifice – and the long-standing Czech failure to grasp Slovak aspirations. Even in the 1980s, after decades of cohabitation, local sociologists maintained that it had not been possible to create a relatively unified Czechoslovak society.

- The fact that the shared state was dissolved twice demonstrates its ephemeral nature. After the first dissolution in 1939, Czechoslovakia was re-established in 1945, enabling the Slovaks to be counted among the victors of the Second World War, despite their earlier collaboration with the Nazis. The second dissolution occurred on 1 January 1993 and resulted from a series of negotiations between political forces elected in the June 1992 parliamentary elections. Until the final stages of the debate, the Slovak side had not clearly articulated a demand for independence. In the end, it was the Czechs who proposed the division, for which they considered themselves better prepared in terms of both human resources and economic capacity. For a long time, the Slovaks struggled to envisage such a separation, yet they gradually expanded their demands and crossed new thresholds, for instance by adopting the Declaration of Sovereignty.

- Czechoslovakia’s cohesion was undermined by differences between its two parts and the nations inhabiting them. While the Czech lands were already highly industrialised by 1918, Slovakia remained predominantly agricultural. This disparity affected levels of prosperity, and the gap was never entirely closed during the existence of the shared state. Among the arguments raised in the political debate following democratisation in 1989 was Czech reluctance to continue ‘subsidising Slovakia’.

- Immediately after the most recent division, it soon became clear that Slovakia was no longer as important for the Czechs as it had been in 1918. The Czechs turned towards the West, and this orientation was largely undisputed. Initially, Slovakia was perceived as a buffer separating the territory under Prague’s control from the unstable regions of Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. Czech elites widely promoted the idea that the Morava River, which flows between the two countries, marked a symbolic dividing line between East and West. The situation was influenced by Slovakia’s geopolitical ambiguity. In the 1990s in particular, the notion of Slovakia as a ‘bridge between East and West’ gained popularity, with the idea of maintaining military neutrality. This was intended to secure Slovakia’s advantageous position as a ‘gateway to the East’ while avoiding entanglement in conflicts among more powerful actors, over which, as a relatively small state, it would have had limited influence.

- In both Czech and Slovak public debates, the issue of the allegedly undemocratic nature of the dissolution regularly resurfaces. The separation was implemented by political forces that, at the time of their election, had not included such a proposal in their platforms, and the population was not consulted via a referendum. However, this line of argument overlooks several important constraints. The first relates to the difficulty of framing a suitable referendum question, as each side envisaged Czechoslovakia differently: the Czechs favoured a strong federal state, while the Slovaks aspired to the loosest possible union. The second constraint was that, following the mid-1992 elections, the state had, in practice, already showed signs of ceasing to function as a federation. Decisions taken by the central government in Prague were increasingly difficult to implement in Slovakia. Postponing the separation would only have aggravated these issues, heightening the risk of disorder or bilateral disputes.

I. Czechoslovakia – a state that fulfilled its historical mission

Although Czech and Slovak national ambitions grew steadily throughout the 19th century, at the outset of World War I, the idea of a shared state remained difficult to imagine for most leading politicians of either nation. Czech aspirations rarely extended beyond a desire to achieve parity with the Hungarians within the Habsburg monarchy. One key expression of this was their repeated pressure on Emperor Franz Joseph I to formally accept the crown of Bohemia. Though he promised to do so – twice, in fact, in September 1870 and again the following year – many Czechs were left with lasting bitterness, as these promises were ultimately unfulfilled. The Austrian ruler was unwilling to set a precedent that might embolden other national groups within the monarchy. At the same time, he did not wish to alienate the German population living in the Czech lands, who comprised around one-third of their inhabitants. Taking the Bohemian crown would have inevitably complicated his relationship with that community. This was because the oath taken by a Bohemian king – last sworn in 1836 by Ferdinand the Benign – included a promise not to diminish the lands of the Bohemian Crown and to seek their expansion.[2] This pledge was fundamentally at odds with the key demand of local Germans, who – recognising that it was no longer realistic to make Bohemia a fully German territory – instead called for the region to be divided along ethnic lines. It was this logic that underpinned the German minority’s opposition to Franz Joseph I accepting the Bohemian crown.

The stance of Czech politicians echoed the ideas promoted in the 19th century by František Palacký, the founder of modern Czech historiography, still remembered as the ‘Father of the Nation’. For a long time, he regarded the Austrian monarchy as the most suitable framework for the Czech nation and its lands, provided that Czech lands – taken as a whole – were granted the broadest possible autonomy. He famously remarked, ‘If Austria did not exist, we would have to create it”,[3] and dismissed concerns about being absorbed into the German sphere with the words, “We were here before Austria, and we will be here after it”.[4] This made the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 and the creation of the dual monarchy all the more disappointing to him, as he had hoped for a structure comprising several equal parts, not one privileging only two.

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk held similar views at the outbreak of World War I. He earned his place in the Czech national pantheon only during the conflict and in its aftermath. Before then, he had criticised the programme for Czech statehood, arguing that a state in which more than one in three citizens spoke German, and which was surrounded by German influence – which he termed the ‘German plague’ – would struggle in future to defend itself or root itself in Czech traditions. In this view, the monarchy served as a buffer protecting the Czechs from ‘chauvinistic’ Germans on one side and ‘Russian autocracy’ on the other.

The weakness of the independence movement was largely a result of a deeply rooted belief in Bohemia in the continuity of Czech statehood under Habsburg rule. Until the first half of the 19th century, coronations of Bohemian kings still took place, often some time after the emperor had received his imperial regalia.[5] The prevailing voices called only for the restoration of full rights within that framework. The rapid economic and social development of the region, especially between about 1870 and 1914, further discouraged revolutionary change.[6] At the same time, however, this period of growth and prosperity enhanced the Czechs’ sense of self-worth and strengthened their national aspirations. Combined with the relative freedoms they enjoyed within the monarchy – particularly in comparison with the Slovaks – this meant that, while they were not yet seeking independence in 1914, Czech elites and society had matured sufficiently in the preceding years to be prepared for it. In fact, the only political group at that time openly calling for independence from the monarchy was the Radical Progressive Party, founded in 1897, which occupied a marginal position on the Czech political scene.[7] Its members were regarded as ‘too radical’ even by Masaryk.[8]

The situation was more difficult for the Slovaks, for whom attaining the level of self-government enjoyed in the Czech lands would have represented a major achievement. The autonomy within the Hungarian part of the Habsburg monarchy was demanded by their main – and until 1913 the only – political organisation, the Slovak National Party (SNS).[9] However, their limited political strength,[10] and the Hungarians’ firm resistance to ‘dividing the Crown of Saint Stephen’, meant that in practice the Slovaks had to place their hopes primarily in external factors. Above all, they looked to the prospect of a European conflict in which Russia would side against Austria-Hungary. They followed closely Russia’s actions in the Balkans, which had played a decisive role in securing autonomy or independence from the Ottoman Empire for various nations in that region, and they hoped a similar scenario might unfold within the Habsburg monarchy.

Great hopes were placed in the heir to the Viennese throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who had presented a vision of the federalisation of the state based on ethnic boundaries. Though the plan was largely unrealistic, the Slovaks were one of the few national groups to support it. This political vision came to an end in 1914 with the Archduke’s assassination in Sarajevo, an event that may have contributed to the prolonged passivity of leading Slovak activists following the outbreak of war, as they waited to see how events would unfold.

The Slovak elite was smaller in number and politically weaker than its Czech counterpart, partly due to the ongoing process of Magyarisation. This led some Slovaks – who had not yet fully developed as a modern nation and lacked a tradition of statehood – to identify with the Hungarian state. At the same time, the position of Czechs – still largely calling only for autonomy within the Habsburg monarchy – offered little basis for the Slovaks to seriously consider forming a common state. As late as 1915, leading Slovak National Party figure Svetozár Hurban-Vajanský, often referred to as ‘the Patriarch of the Slovaks’, reacted to the first ideas of such a union by calling it ‘absolute madness’.

- The background and reasons for establishing a common state

Cooperation between Czech and Slovak activists during World War I, particularly abroad, laid the foundations for a Czecho-Slovak state. This cooperation was facilitated by linguistic proximity and financial support from émigré communities, especially those in the United States[11]. Czech–Slovak military units formed in Entente countries also played an important role, later helping to secure the borders of the newly established state. An external factor was equally decisive: the collapse of Austria-Hungary, brought about by the empire’s wartime defeat and growing centrifugal forces within the multi-ethnic Habsburg monarchy. The final efforts to preserve it failed – the manifesto by Emperor Charles I of 16 October 1918 (To My Faithful Austrian Peoples), which proposed transforming the monarchy into a federation of national states, found little support.

The last days of October 1918 proved crucial from both the Czech and Slovak perspectives. On 28 October, the establishment of the new state was proclaimed in Prague, and two days later the Slovaks confirmed their intention to join it through the Martin Declaration. The immediate trigger for declaring independence came with a note issued on 27 October by the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister, Count Gyula Andrássy the Younger, in which he accepted the terms of an armistice set by Washington. In it, he explicitly endorsed only the American stance on the ‘rights of the peoples of Austria-Hungary, especially the Czechoslovaks and the Yugoslavs’. While the author likely did not intend this as recognition of full independence, it was interpreted as such in subsequent reports and helped set in motion a chain of events.

In the following days, Hungary’s new liberal-left Prime Minister, Mihály Károlyi, offered the Slovaks autonomy within Hungary. However, the offer came too late. This did not, however, mean a straightforward abandonment of the territory known in Hungary as Upland (Felvidék). Until mid-1919, Budapest made unsuccessful attempts to reclaim the area militarily. The heaviest fighting occurred in May and June 1919, after the communist coup in Hungary and the country’s suspension of hostilities with Romania. Carpathian Ruthenia also severed its centuries-long bond with Hungary. On 8 May 1919, the Central Ruthenian National Council expressed support, in the so-called Uzhhorod Memorandum, for joining Czechoslovakia. However, it was not the clashes with Hungary that constituted the first military engagement of the newly formed state. Those had already taken place in January 1919, when conflict erupted with Poland over the division of Cieszyn Silesia. One of the main reasons why Prague launched an attack in that area was its intention to secure access to the only railway connection between the Czech lands and eastern Slovakia – the Košice–Bohumín Railway.

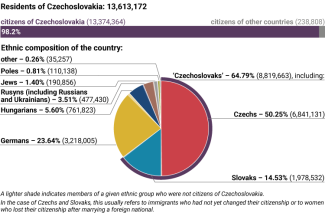

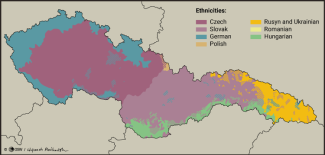

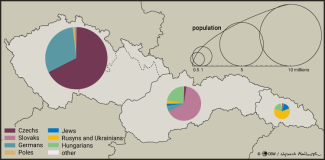

The joint state with the Slovaks allowed the Czechs to achieve the goal articulated by Masaryk: escaping encirclement by German influence. The concept of a Czechoslovak nation was developed to secure a dominant position for the ‘Czechoslovaks’. According to the 1921 census, this artificially constructed nation comprised just under 65% of the population of Czechoslovakia. This framing helped gain Entente support for the new state – an outcome less likely had the Czechs been presented as the sole national core (see Chart 1 and Map 1). It also justified designating the Slovaks (nearly 2 million) as a constituent nation, while the far more numerous Germans (around 3.2 million) were classified as a minority (hence their use of the term Volksgruppe – ‘ethnic group’ – rather than ‘minority’). Moreover, it placed the Czechs (6.8 million) in a politically more comfortable position than they would have had in a state where nearly one-third of the population consisted of an unfriendly or even hostile German-speaking community (see Map 2).

The Czechs also drew on Swiss and American models. The latter was explicitly referenced in the so-called Washington Declaration of 18 October 1918, which proclaimed the creation of Czechoslovakia. The declaration was widely publicised in the United States and received a highly positive response from the American public.[12] At the same time, the unitary structure of the future state distinguished it from the USA and Switzerland. The failure to honour promises of a looser confederal or federal arrangement later led to disappointment among some Slovaks. Among the disillusioned was the Slovak diaspora in North America, which had generously supported Masaryk and his associates during the war, expecting that Slovakia would be granted autonomy. For Masaryk himself, references to the above-mentioned state models primarily meant embracing democratic principles and the assumption that the political nation would be formed by all citizens, regardless of the language they spoke.

Chart 1. Ethnic composition of Czechoslovakia in 1921

Source: author’s own study based on the 1921 census and data from national statistical offices.

Map 1. Ethnic groups dominant in various regions of Czechoslovakia

Source: based on a map prepared by the Military Geographical Institute (Vojenský zeměpisný ústav) in Prague in 1931, which was based on the results of the 1930 census. The division of the ‘Czechoslovak nation’ into Czech and Slovak components is delineated using a map derived from the same census and published in 1938 by Verlag Karl H. Frank.

Map 2. Ethnic composition of the individual parts of Czechoslovakia

Source: based on the 1921 census results; supplementary data from: ‘Czech Demographic Handbook – 2022’, Czech Statistical Office, 23 November 2023, csu.gov.cz; G. Šamanová, ‘Národnost ve sčítání lidu v českých zemích’, Centrum pro výzkum veřejného mínění, 2005, cvvm.soc.cas.cz; Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic, scitanie.sk.

Following the collapse of Austria-Hungary – a large, multi-ethnic state – there were widespread concerns among the victorious powers (as well as among the Czechs and Slovaks themselves) about the ability of smaller political entities to survive on their own. The Allies also sought to avoid excessive instability in the region. France, in particular, aimed to create a network of substitute alliances to fill the void left by Russia, which had plunged into chaos. This was one of the reasons why Czech representatives at the Paris Peace Conference (and beforehand) lobbied for the creation of a state that would include not only the traditional Czech lands. In his most ambitious plans, Masaryk even envisioned broader regional consolidation through the creation of a corridor linking Czechoslovakia with Yugoslavia.

One of the major successes of the young state’s diplomacy was convincing the Allies to preserve the broadly understood historical borders of the Bohemian Crown (excluding the most contentious areas, raised mainly to create room for negotiating concessions – such as Lusatia and the Kłodzko Land – and without part of Cieszyn Silesia), even though the frontier lands were largely inhabited by Germans. Masaryk argued that without the industrial plants concentrated in those areas, the country would be economically fragile, and the loss of those regions would weaken its defences. As a result, Czechoslovakia inherited about 70% of the industry of the former monarchy, despite absorbing only around 25% of its population and 20% of its territory.[13] At the height of its interwar economic strength, it ranked among the wealthiest countries in Central Europe (see Map 3), with GDP per capita 12th on the continent (almost equal to Italy’s) and 18th in the world. Economic and security arguments were essential complements to references to Czech statehood traditions, particularly given that, at the same time, Hungarian historical claims to Slovakia were being firmly rejected.

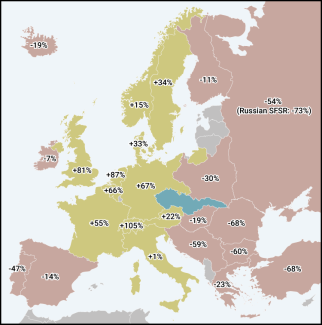

Map 3. Real GDP per capita of Czechoslovakia in 1929 compared to other European countries

Source: author’s own estimates based on data from the Maddison Project (University of Groningen).

For the Slovaks, who had no tradition of their own statehood, union with the Czechs offered a greater degree of political agency than they had experienced within the Hungarian state. This was especially true after the creation of the dual monarchy in 1867, when Budapest pursued an approach to minority policy that was markedly different from that of Vienna. While in the Austrian half of the empire citizenship was understood as loyalty to the authorities regardless of ethnicity, and language questions constituted no major issue, the Hungarian half witnessed the advance of Magyarisation. Between 1875 and 1918 – roughly two generations – there were no secondary schools teaching in Slovak. In 1875, the Hungarian authorities banned the national cultural organisation Matica slovenská, which had been established only 12 years earlier. The development of a Slovak national elite was therefore severely constrained, and by 1918 such elites remained relatively small in number. This increased the role of nationally conscious Slovak emigrants in discussions with the Czechs, particularly those in North America – cities such as Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Chicago probably hosted the largest Slovak communities in the world at the turn of the 20th century.[14] In this context, a joint state with the Czechs created opportunities to cultivate broader elites, notably through the reintroduction of education in the Slovak language and the establishment of cultural institutions. In 1919, Matica slovenská resumed its activities, a university was founded in Bratislava, and the following year the Slovak National Theatre was created. The Czechs largely replaced the Hungarians in public administration and other key sectors of society, as the Slovaks lacked a qualified workforce in sufficiently large numbers.

Thanks to diplomatic efforts, the Slovak part of the new state was extended to include territories with a predominantly Hungarian population. The Allies were persuaded by arguments about the importance of access to the Danube and the use of Europe’s second-longest river as a natural border. As a result, Hungarians made up 22% of the population in Slovakia. For many months after the end of the First World War it was far from certain that Pressburg – renamed Bratislava only in 1919 – would be included in Slovak territory. The city, which after internal debates became the capital of Slovakia as an administrative unit of the First Czechoslovak Republic, was inhabited at the outbreak of the war by only 15% Slovaks, with Hungarians and Germans accounting for 42% and 41% of its population respectively. The first post-war census showed Slovaks comprising barely one-third of the population, with Germans forming the largest group. This shift likely reflected changes in identity rather than large-scale migration. Slovaks educated in the Hungarian system under the former state had often advanced by remaining loyal to Budapest. Many did not possess a strongly developed national consciousness, and fluency in at least two languages was common. Some have even argued that in 1918, had a referendum been held, a majority of Slovaks might have opted to remain part of Hungary.[15]

Regardless of the favourable historical circumstances, it is difficult to imagine the birth of Czechoslovakia without two men who played a decisive role in its creation – Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and Milan Rastislav Štefánik. Both were born under the Habsburg monarchy, in areas close to today’s Czech–Slovak border, just 50 kilometres apart.

Masaryk was born directly by that border, which in this region follows the course of the Morava River. He would later be elected to the country’s highest office four times and serve as president for a record 17 years. He was exceptionally well placed to think beyond the framework of a nation state. He had grown up in a multi-ethnic kingdom. His father, Jozef Maszárik, was Slovak (Tomáš changed the family name to the Czech form, Masaryk, during secondary school), and his mother, Terezie, spoke German more fluently than Czech. The future statesman came from the Slovácko region, sometimes referred to as ‘Moravian Slovakia’, which was culturally closer to western Slovakia than to Prague. In this regional sense of identity, he described himself as a Slovak, and the idea of a single Czechoslovak nation may have felt particularly close and natural to him.

He was the one who, as early as September 1914, put forward the concept of a joint state for Czechs and Slovaks. Over time, he gained the support of Czech and Slovak émigré organisations, as well as that of the domestic Czech anti-Austrian underground group, which consistently backed him and later became known as the Maffia. Masaryk’s emergence as the leading figure in the independence movement is all the more remarkable, considering that after the last pre-war elections to the Austrian Imperial Council in 1911, he was the sole representative of his own formation – the Czech Progressive Party – which, even among Czech political entities, ranked only 11th, receiving a mere 0.4% of the vote in the Czech lands (where it was also outperformed by eight German parties and two Polish ones). Especially towards the end of the war, Masaryk succeeded in gaining access to US President Wilson and influencing his decisions. This contributed to Wilson’s eventual abandonment of the idea of preserving Austria-Hungary – in his famous Fourteen Points, announced in January 1918, he had initially called only for the autonomous development of the empire’s ethnic groups.

In 1915, the idea of a joint state was adopted by Štefánik – a former student of Masaryk in Prague and 30 years his junior. He quickly became a key Slovak figure in the still vague project. By early 1916, he had assumed the post of vice-chairman of the newly established Czechoslovak National Council, which by the end of the war the Entente powers recognised as the representative body of the future state. As a high-ranking officer in the French army (he rose to the rank of general), he brought invaluable contacts with leading French politicians to the cause. Štefánik played a decisive role in creating the foundations of the Czechoslovak army – for most of the conflict he organised Czecho-Slovak legions in Allied countries (France, Russia, Serbia, and Italy), and in the new state he became the first Minister of War. His brilliant career was cut short by a plane crash in 1919, shortly after the formation of Czechoslovakia.

Among the key figures who significantly contributed to the creation of Czechoslovakia were Edvard Beneš, Andrej Hlinka, and Vavro Šrobár. The first of these served as head of the Maffia, later becoming secretary general of the Czechoslovak National Council and a delegate to the Paris Peace Conference. Following the establishment of the independent state, he remained Masaryk’s closest associate. Masaryk ensured that, throughout his presidency at Prague Castle – until 1935 – no one else was entrusted with control of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Hlinka, meanwhile, played an important role in 1918 in persuading sections of the Slovak elite who did not fully identify with Štefánik, who had long lived outside Slovakia. It was largely under the influence of Hlinka – a politician, journalist, and priest revered as a martyr for the Slovak cause (having spent several years in prison before the war for speeches the Budapest authorities deemed ‘anti-Hungarian’) – that the underground Slovak National Council decided in May 1918 to back the Czecho-Slovak orientation. Hlinka openly advocated for this step, and his words at the time – ‘a thousand-year marriage with the Hungarians has failed’ and the two sides must part ways – became widely quoted. He was one of the signatories of the Martin Declaration, in which the Slovak elite endorsed the creation of Czechoslovakia. However, Hlinka’s initial enthusiasm soon gave way to disappointment over the lack of autonomy for Slovakia and his own political marginalisation. Despite being a co-founder and, from 1913 until his death in 1938, the chairman of the Slovak People’s Party,[16] he was not included in the new Czechoslovak government. His later attempt to advocate for greater Slovak political agency at the Paris Peace Conference – for which he travelled using a Polish passport issued under a false name – triggered a diplomatic scandal. Upon his return to Czechoslovakia, he was interned (despite holding a seat in parliament) on charges of treason, although he was released after regaining his parliamentary mandate. The party he led remained the largest political force in Slovakia throughout the First Republic and the principal advocate for its autonomy.

Šrobár was the only Slovak to sign the resolution declaring the independence of Czechoslovakia in Prague on 28 October 1918. As a member of the Executive Committee of the Slovak National Council, a body elected in Martin two days later, he acted as a liaison between the two nations during the formation of the new state. In its first government, he was one of only two ministers from Slovakia, alongside Štefánik.

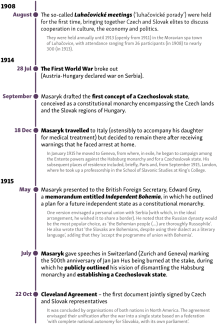

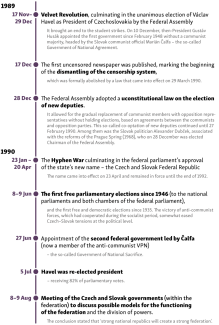

Timeline of the creation of Czechoslovakia

Political drivers

Czechs and Slovaks were primarily united by political and ethno-linguistic factors. Politically, the Czechs sought to strengthen their position in relation to the German minority, while the Slovaks aimed to do the same with regard to the Hungarian minority. Both also wished to safeguard themselves against potential revisionism from Berlin (or Vienna) and Budapest (see above). Whenever the Czechoslovak state failed to fulfil this function, or when such external threats were no longer perceived as pressing, centrifugal tendencies intensified. Such a situation occurred in autumn 1938, when Prague yielded to the Munich Agreement and, following the First Vienna Award, Slovakia lost its southern borderlands to Hungary. Separatist aspirations in Slovakia gained momentum, further fuelled by pressure from Nazi Germany. The Second Republic, formed at this time, adopted the name Czecho-Slovakia (with a hyphen – see box ‘The Hyphen War’), emphasising the distinct character of its Slovak component. Slovakia was granted long-awaited autonomy and, in March 1939, proclaimed independence, though in practice it became a satellite state of Nazi Germany. Nearly three decades later, during the crisis triggered by the Warsaw Pact invasion of post-war Czechoslovakia, Slovakia succeeded in pushing through formal federalisation from the beginning of 1969. After 1989, the two nations perceived external threats differently. The Czechs, following the post-war expulsion of Germans and the democratisation of their western neighbour, no longer felt insecure. The Slovaks were less confident in their position and for a long time sought to reconcile their desire for greater political agency with the preservation of a looser union with Prague (for example, in the form of a confederation). In particular, they were keen to maintain unity in defence policy.

The Hyphen War At various points during the coexistence of Czechs and Slovaks, the smaller of the two constituent nations sought to emphasise its distinctiveness through the specific spelling of the state’s name – Czecho-Slovakia instead of Czechoslovakia. The best-known episode of this dispute occurred in the spring of 1990 and has gone down in history as the Hyphen War. The episode is referred to as Pomlčková válka by Czechs and Pomlčková vojna by Slovaks, with pomlčka being the word for dash in both languages. Later, linguists pointed out that the term was actually a misnomer – what was at stake in these debates was not a dash, which serves other functions such as introducing interjections, denoting dialogue, or replacing repeated elements in a sentence, but rather a shorter graphic mark, called a hyphen or spojovník in Czech and Slovak, used to form compound words. Interestingly, while the original name became established and entered the historical record in both countries, the correct form is usually used in English speaking environments. Tensions over the state’s name can already be discerned in the linguistic duality of two key agreements signed by Masaryk in the United States before the formation of Czechoslovakia: the so-called Pittsburgh Agreement of 30 May 1918 (with representatives of Czech and Slovak organisations in the United States) and the Washington Declaration of 18 October 1918 (written in English and also signed by the Slovak Milan Štefánik, among others). The former used the term ‘Czecho-Slovak state’ (hyphenated), whereas the latter referred to a ‘Czechoslovak state’ (without a hyphen) and even mentioned a ‘Czechoslovak nation’. This was likely no accident: the first agreement was meant to win over Slovaks to the idea of a common state, while the second sought to convince the Entente powers that there was one large nation that would dominate the state, thereby avoiding the impression of creating a new version of the multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Martin Declaration adopted on 30 October 1918 by the Slovak National Council – the highest body representing the Slovak nation – referred to the Slovaks as part of the ‘Czecho-Slovak nation,’ which it claimed had the right to self-determination. The document used the spelling ‘Czecho-Slovak’ four times and ‘Czechoslovak’ once. There was no such ambiguity in the 1920 constitution of the First Republic, which consistently omitted the hyphen. Nevertheless, until that constitution was adopted, international communications generally used the hyphenated form – for example, it appears in both the English and French versions of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, the peace agreement signed on 10 September 1919 between the Entente powers and Austria. The first postage stamps – issued in December 1918 and designed by the renowned artist Alfons Mucha – were inscribed with ‘Czecho-Slovak Post’ (with a hyphen). In contrast, the authors of the provisional constitution of 1918 managed to avoid using the name of the state altogether in order to sidestep the controversy. The intensifying Slovak campaign for autonomy in the 1930s, together with the weakening of Czechoslovakia following the Munich Agreement (30 September 1938), marked a new chapter in its history. From 1 October 1938, when the first German units began occupying the borderlands, the state is already referred to as the Second Republic. After President Beneš abdicated (5 October) and most Slovak political parties proclaimed autonomy in Žilina the following day, Jozef Tiso became the prime minister of the new autonomous government (7 October). Formal constitutional amendments were adopted only on 22 October (some constitutional scholars argue this was unlawful), and from the following day the state was officially named the Czecho-Slovak Republic (Česko-Slovenská republika). It lasted until 15 March 1939, when Germany started to occupy the remaining Czech lands and Slovakia declared independence shortly beforehand. In order to distance itself from these events, while still evoking the legacy of the First Republic’s golden years, the government-in-exile used the non-hyphenated spelling. A uniform version of the name – with an added adjective (Czechoslovak Socialist Republic) – was also used during the era of real socialism, which can further be explained by the communist authorities’ desire to suppress centrifugal tendencies. Onomastic debates flared up again with renewed intensity after the opening of public discourse at the end of 1989. Whereas in Poland the constitutional amendment restoring the historical name Rzeczpospolita Polska (Republic of Poland) came into force on 31 December 1989, it took somewhat longer for the Czechs and the Slovaks to remove the word ‘Socialist’, associated with communism, from the country’s name. The debate was initiated by a speech in the Federal Assembly by President Václav Havel on 23 January 1990. He proposed that the country be renamed simply the Czechoslovak Republic (Československá republika; in both Czech and Slovak, only the first word of such names is typically capitalised). Czech deputies also supported dropping only the term ‘socialist’ and advocated the use of the established term ‘Czechoslovakia’. They invoked the negative associations linked to the hyphenated version used in the autumn of 1938. Slovak deputies agreed on removing the word ‘socialist’, but they viewed the entrenched name without a hyphen as a symbol against which their compatriots had long struggled. The Slovak government therefore proposed a spelling with a hyphen and capital letters (Federácia Česko-Slovensko or Republika Česko-Slovensko). Over time, Havel accepted the hyphenated version with only one capital letter (Republika česko-slovenská)and even submitted it as a formal proposal himself. At the same time, however, he also supported a rival parliamentary bill that used no hyphen (and included ‘federation’ in the name), which provoked outrage among the Slovaks. The heated debate unfolded not only in parliament but also in the media and on the streets. In Bratislava, some individuals even went on hunger strike until a version with a hyphen and capital letters was adopted. On 29 March 1990, the country’s name was finally changed, with the new title having two written forms: the Slovak version was Česko-slovenská federatívna republika (with a hyphen), while the Czech version omitted the hyphen. In international use, the latter became the standard. This was the result of a compromise reached when no unified proposal could secure approval. It was put forward by the rapporteur MP Miloš Zeman, who would later become Czech prime minister and president. Václav Havel, who had come directly from hospital, urged that the issue be resolved promptly ‘for international reasons’. This solution failed to gain unequivocal support and sparked further controversy among Slovak public. That same evening, a demonstration erupted in Bratislava. Protesters carried slogans such as ‘We want the dash and a capital S’, and labelled the MPs who had voted for Zeman’s proposal as ‘traitors’. The name thus lasted only 25 days. The day after the change was implemented, further negotiations began, and on 5 April Havel convened a meeting of leading politicians from both sides, along with linguists, at his residence in Lány. He solemnly declared that the doors would remain locked until an agreement was reached. The final agreement, proposed by the Slovak speaker of the federal parliament, Alexander Dubček, and in force until the dissolution of the common state, referred to the Czech and Slovak Federative Republic (with a spelling in capital letters that violated the rules of both languages). One might therefore say that the resolution to the Hyphen War turned out to be the conjunction ‘and’ (i in both Czech and Slovak). Nevertheless, in its abbreviated form, two names continued to circulate internationally in parallel: Czechoslovakia (used by Czechs) and Czecho-Slovakia (used by Slovaks), with translations reflecting the source language of the original. The intensity of debate on what was, in practical terms, a minor issue – both in parliament and among the general public – foreshadowed the imminent collapse of the joint state. While optimists tried to interpret the compromise as a positive sign, proof that a mutually acceptable solution could be found, these hopes quickly faded after the parliamentary elections in June 1990, which triggered a serious debate over the degree of centralisation in the country and the distribution of powers among its institutions. Years later, Milan Zemko of the Institute of History at the Slovak Academy of Sciences observed: ‘Czech politicians and the media were asking why we were arguing over a triviality, but they themselves were unable to give ground for a long time’. He added that for Slovaks the matter was of symbolic importance, since a name could either signal ‘the fundamentally unitary nature of the state or emphasise that it consists of two equal parts’.[17]

Cultural and linguistic cohesion

The cultural – and particularly linguistic – proximity contributed to the emergence of the idea of a single nation and language, which featured in certain strands of thought in what are now the Czech Republic and Slovakia during the 19th century. This idea most often took the form of viewing the Slovak language as a dialect of Czech and later – especially in the interwar period – as the notion of a Czechoslovak nation or language. These concepts were primarily widespread among Protestant communities in both countries. Slovak Evangelicals continued to use the Czech Protestant translation of the Bible – the Kralice Bible from the late 16th century – until the second half of the 20th century, and their liturgy was conducted entirely in Old Czech.

The idea that Czechs and Slovaks constituted a single nation was first articulated among exiled Czech and Slovak Protestants at the end of the 17th century, when they found themselves together in Saxony after one of the Habsburg-imposed waves of re-Catholicisation. From the 15th to the 19th century, the language of Slovak literature was a Slovakised form of Czech.[18] It was not until the 1840s that a clearly separate path was pursued, initially through the work of national activist and codifier of the Slovak language, Ľudovít Štúr, who rejected the ‘offer’ of Czech national revivalists to adopt their language as a common tongue. The unequal status of both languages in the shared state – particularly evident during the First Republic – sensitised Slovak elites to the signs of Bohemisation of their language. Earlier, Slovak linguistic circles had sought to distance themselves from Hungarian influences, in response to the experience of Magyarisation at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

After 1918, there were virtually no representatives of the Slovak elite who supported Czechoslovakism in an ethnic sense, although some indirect accounts suggest that Štefánik privately expressed such convictions. He is even said to have proposed naming the newly established country simply the Czech Republic.[19] A somewhat more resilient – though eventually also increasingly marginalised – approach in Slovakia accepted Czechoslovakism in a political sense (with Šrobár among its adherents). This concept, even in its ethnic interpretation, was quite popular among leading Czech figures. One of them was Beneš, Masaryk’s successor as head of state. As late as the 1940s, he insisted that ‘no one and never’ would convince him of the distinctiveness of the Slovaks as a nation, or of the Slovak language as anything more than a dialect (however, despite being raised mostly in Prague, the first post-war president of the country spoke fluent Slovak). A similar view was held by Ferdinand Peroutka, an influential interwar intellectual, who argued that only Czech should be used in written texts and formal situations.

Regardless, efforts to forge cohesion focused on highlighting past periods when the present-day Czech Republic and Slovakia (or their parts) constituted a single entity, as well as on individuals seen as bridging both nations. In both respects, options were limited. Apart from the Habsburg era, the shared past was primarily centred on the time of Great Moravia, which came to be portrayed in historiography as a kind of proto-Czechoslovakia. Interestingly, it lasted roughly as long as Czechoslovakia itself – founded in 833 and disintegrating by 907 – which, from a historical perspective, was a relatively brief period. Its actual relevance to Czechoslovakia was virtually negligible – not only due to its short duration, but also because of the gap of more than a thousand years. Moreover, for most of its existence, the core of Great Moravia encompassed Moravia and Slovakia, while the historical region of Bohemia was only incorporated around 888, and just six years later their paths diverged. According to some historians, the lands of the Vistulans tribe – largely overlapping with present-day Lesser Poland (with Kraków) – remained part of Great Moravia for significantly longer.[20]

In the shared mythology of the new state, the figures of Saints Constantine (Cyril) and Methodius served as a key reference to this historical period. The cult of the Thessalonian Brothers was revived in the second half of the 19th century in connection with the millennial anniversaries of their arrival in Moravia (1863), Cyril’s death (1869), and Methodius’s passing (1885). To mark the last of these events, Jan Matejko – the son of a Czech – painted a depiction of the missionaries, which still hangs in the basilica in Velehrad as a ‘gift from the Polish nation’. The brothers worked in the Great Moravian Empire, and between 869 and 885 Methodius also baptised the ruler of Bohemia, Bořivoj I. As apostles to the Slavs, they were ideally suited to promoting the harmonious coexistence of the two nations belonging to this ethno-linguistic group. Moreover, in the context of the First Republic – generally sceptical of the Catholic Church – their legacy was invoked e.g. by Masaryk and, centuries earlier, by Jan Hus, whom the president admired. Even after the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, the feast day of the missionaries (5 July) remains one of the relatively few non-exclusively religious public holidays observed by both successor states (see box ‘Disputes over the Holiday Act and the Marmaggi Affair’). The day is associated with the importance of acquiring knowledge, and in particular with cultivating care for one’s own language. Saint Cyril created the first Slavic script – Glagolitic – and, together with his brother, began translating the Bible and liturgical texts into the Slavic languages.

Today, there is no doubt that language – or more broadly, ethnic identity – draws the two countries and nations closer together. Czech and Slovak both belong (alongside Polish) to the group of West Slavic languages, and within it form the Czech-Slovak branch, also referred to as the southern branch. The similarity of dialects and customs is most evident along the border between the two countries, where the transition between dialects is fluid, creating a dialectal continuum. Eastern Moravian dialects, especially those of the Kopanice region, share many features with Slovak and are considered transitional. Some linguists even regard them as closer to Slovak. Their classification within a given language is also influenced by historical and political factors. Periods of shared statehood were marked by a strong influence of the Czech language – more widely used in the media and administration – on Slovak. This influence has not diminished following the division of Czechoslovakia. The reverse effect is much less common. Nevertheless, mutual passive bilingualism, particularly among middle-aged and older generations, remains widespread.[21]

Divergences and differences

Czechs and Slovaks were divided primarily by the fact that, despite cultural proximity, they constituted different nations – in defiance of attempts to deny this reality, first through a broad interpretation of the concept of the Czech nation and later by promoting the artificial construct of a Czechoslovak nation. At the time the joint state was established, the Slovak nation had already almost completed its process of formation, and sharing a state with the Czechs enabled the completion of the final stage of this development. The assumption held by some advocates of Czechoslovakism, above all Masaryk, that even if a Czechoslovak nation did not yet exist, it would emerge naturally through cohabitation within one state, proved unfounded. This did not occur and, as noted by Professor Jan Rychlík – a historian specialising in the history of Czechoslovakia and also an ethnologist – there are no known historical examples of two fully formed nations merging into one. By contrast, the reverse process can and does take place – for example, as a result of the division of a single nation into different states.[22] He argued that a natural phenomenon is the tendency for every nation to seek a degree of autonomy and eventually to pursue the establishment of its own state, as was also the case with the Slovaks.

That a relatively unified Czechoslovak society had not developed after decades of coexistence was a conclusion drawn even in the 1980s by local sociologists. In terms of structure and worldview, two clearly distinct components – Czech and Slovak – remained identifiable.[23] This, however, does not mean that under more favourable circumstances both nations could not have coexisted more harmoniously, or even developed a shared secondary identity (comparable with a European one). Such outcomes might have been encouraged, for example, by a joint military effort against Germany (which ultimately did not occur in 1938) or by greater Czech sensitivity to Slovak political aspirations.

Almost from the outset of coexistence within Czechoslovakia, Slovak ambitions for greater involvement in governance and the absence of autonomy for Slovakia – promised in the Pittsburgh Agreement signed by Masaryk in May 1918 – proved problematic. The latter, in particular, significantly eroded the trust of much of the Slovak elite towards Prague and was repeatedly cited as evidence that the state had been built on ‘a deception of the Slovaks’.[24] The Czechs initially talked about waiting for more stable times to address the issue, but later rejected the demand outright. They were driven by fears that granting autonomy would lead to similar claims from the German minority and, additionally, would expose the myth of the dominant ‘Czechoslovak nation’ as a fiction. While Slovak acceptance of Czechs holding administrative positions immediately after 1918 was initially met with understanding, by the 1930s – when a new generation of Slovaks emerged who were qualified to hold such roles – this state of affairs was increasingly resented. Czechs often interpreted the growing criticism as ingratitude. Similarly, Prague often failed to understand the swift articulation of new autonomist demands after 1989.

Slovak ambitions were only briefly and symbolically realised in 1969, when formal federation was introduced. It was the only substantial reform developed during the 1968 political liberalisation period – the Prague Spring – to come into effect. However, this occurred during the communist regime (1948–1989), a time when centralised governance intensified and centrifugal tendencies were actively suppressed. The ‘democratic centralism’ practised in communist states required unconditional subordination of lower administrative units to higher ones, effectively contradicting the principles of federalisation. While this state of affairs supported the continued existence of the unified state, it also fuelled Slovak disillusionment and discredited the idea of federation, which was increasingly regarded as yet another Czech manoeuvre to retain control over Slovakia.[25]

Differences in national identity are reflected in distinct historical memories and national symbols. The historical trajectories of the two nations are asynchronous: while the Czechs tended to look westwards, having for centuries been part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (with Prague even serving as its capital twice), the Slovaks oriented themselves more towards the south. From the first half of the 11th century until 1918, Slovak history was closely tied to Hungary. Between 1563 and 1830, eleven Habsburg rulers of Hungary were crowned in what is now Bratislava (then Pressburg), with only two coronations held elsewhere during that time.

As a result of these differences, key moments in Czech history – such as the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, which marked the end of the native nobility and the beginning of re-Catholicisation – held little significance for the Slovaks on the other side of the Morava River. Slovaks did not share the Czech reverence for the Hussite tradition.[26] Similarly, Catholic patron saints of the Czech lands such as St Wenceslas and St John of Nepomuk, meant little in Slovakia, where strong Marian devotion prevailed, and the cult of King Saint Stephen[27] had for years been promoted by Budapest. A symbolic reflection of these tensions was the prolonged debate over the form of the national holidays law, which was not adopted until 1925 (see box ‘Disputes over the Public Holidays Act and the Marmaggi Affair’).

To this day, Czechs and Slovaks interpret key figures of the common state differently. While Masaryk enjoys high regard in both nations, he is virtually untouchable only in the Czech lands. Slovaks generally view Beneš negatively, in contrast to the broadly favourable perception he retains among Czechs, despite ongoing debates about some of his political decisions. Conversely, Gustáv Husák – the leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia during the 1970s and most of the 1980s – ranked seventh in a nationwide public broadcaster poll for the greatest Slovak in history conducted in 2019. This can be attributed to memories of relative economic improvement during his tenure, his role in securing federalisation, and respect for his contribution to the 1944 anti-German uprising. However, only 10% of Czechs assess his legacy positively, while more than half view it negatively.[28] A wave of indignation and astonishment among Czech politicians and journalists followed the laying of flowers on Husák’s grave by Prime Minister Fico and the nationalist leader of his junior coalition partner in January 2024, marking the anniversary of his birth.[29]

Disputes over the Public Holidays Act and the Marmaggi Affair Czechoslovakia adopted the Public Holidays and Commemorative Days Act in 1925. Earlier, in 1919, there had only been agreement that 28 October should hold a special place in the calendar as a commemoration of the founding of the state (and that 1 May should also be included as Labour Day). For comparison, around the same time, similar matters were regulated in Poland, where in 1919 the celebration of the anniversary of the 3 May Constitution was established (11 November – National Independence Day – became a statutory holiday only in 1937), and the holiday calendar, based on church feasts, was formalised between 1924 and 1925. The protracted debates on this issue in Czechoslovakia stemmed from differences in the perception of various figures, events, or church holidays between Czechs and Slovaks, as well as within Czech society itself. These divergences translated into the actions of political parties. As the state initially adopted Austro-Hungarian legislation and gradually amended it, the calendar in force at first remained that of the Habsburg monarchy. In the debates over its revision, the most contentious figures were St John of Nepomuk and Jan Hus. The former was one of the main patron saints of the Czech lands, whose feast day (16 May) had been a public holiday since the 1770s.[30] The latter was not commemorated with a holiday, yet he was counted among the most important historical figures by, for instance, President Masaryk. The link between John of Nepomuk and Hus was not accidental: especially from the 19th century, Czech elites increasingly believed that Vienna had promoted the cult of the former to marginalise the latter. In the early days of the First Republic, statues of the saint were sometimes destroyed as symbols of the previous regime. Attempts to introduce a holiday related to Hus failed twice (in 1920, proposed by Czech nationalists, and in 1923, by the left), in part due to opposition from Slovak MPs but also owing to the reluctance of Czech Christian Democrats, led by the Catholic priest Jan Šrámek (who headed the party in Moravia from 1919 and nationwide from 1922 to 1938). The act of March 1925 ultimately designated the following as official holidays (specifically, ‘memorial days’ of Sunday status, i.e. work-free) in the state calendar: the anniversary of the burning of Jan Hus (6 July), which was often regarded as a hostile gesture by Catholics – most commonly Slovaks , but also many Czech Catholics; the feast of St Wenceslas (28 September), a figure largely indifferent to Slovaks; and the feast of Saints Cyril and Methodius (5 July). The inclusion of the latter proved to be a well-judged decision – it addressed the need for references to the relatively brief shared history of these lands (Great Moravia), and invoked the Czech and Slovak national revivals of the 19th century, which were rooted to a great extent in the cultivation of their respective languages. The Thessalonian Brothers remain particularly revered in Slovakia and Moravia as the fathers of Slavic literacy, which laid the foundations for later identity, and 5 July is still a public holiday in both the Czech Republic and Slovakia. In addition to holidays clearly and exclusively associated with the Czechs – relating to Hus and St Wenceslas – 28 October carried a similarly problematic connotation for many Slovaks, as the Czechoslovak equivalent of an independence day. It commemorates events in Prague in which only one Slovak played a significant role (see Chapter 3 of this section), while its Slovak equivalent is the anniversary of the adoption of the Martin Declaration (30 October 1918), which was not included in the official calendar. An attempt to add this date was made in 1937 by Hlinka’s party, which was campaigning for Slovak autonomy. While Slovaks observed 28 October as a holiday nonetheless, for the Germans and Hungarians living in Czechoslovakia, the day – particularly in the early years of its existence – served as an opportunity to express opposition to state policy and their status as minorities. The exclusion, under the 1925 act, of Easter Monday, along with the days immediately following Christmas and Pentecost from the list of work-free days was also negatively received, not only in Slovakia. These were reinstated only through a regulation issued on 9 March 1939. The government in Prague, however, supported the commemoration of the anniversary of Štefánik’s death (4 May) in Slovakia, honouring a figure considered significant for Czechoslovakia. The Slovak State established in 1939 distanced itself from holidays perceived as overly Czech – state holidays commemorating Hus, St Wenceslas, and the founding of Czechoslovakia were removed from the official calendar, with only the feast of Saints Cyril and Methodius retained (and the anniversary of the founding of the Slovak state on 14 March added – a date still marked in extremist circles today). A key episode in the history of public holiday debates in interwar Czechoslovakia was the international dispute with the papacy sparked by the new law, known as the Marmaggi Affair. Francesco Marmaggi, the local apostolic nuncio, disapproved of the preparations for large-scale state celebrations of the first observance of the holiday commemorating Hus (6 July 1925), who at that time was regarded by the Catholic Church as a heretic who had defied the Pope. The final straw came when Masaryk flew a Hussite flag (bearing a chalice) over Prague Castle, which the nuncio interpreted as a provocation against Catholics, prompting him to leave the country in protest. Prague’s actions were criticised by Hlinka’s party, whose newspaper Slovák wrote of ‘the impudence of the Czech Hussites’ who ‘incited, insulted, and attacked the representative of the Holy Father’. The incident also met with disapproval from the German minority and from a significant portion of the Czech public – around 80% of whom still considered themselves Roman Catholic at the time. Although diplomatic relations with the papacy were not severed, they were downgraded to the level of chargé d’affaires. This situation persisted until January 1928, when a new nuncio arrived in the country. His appointment was made possible by a compromise under which Prague pledged not to extend patronage to celebrations commemorating Hus. In addition, the boundaries of Slovak dioceses were to be adjusted so that no part of the country would fall under Hungarian ecclesiastical jurisdiction. This was formally achieved only in 1977, although from 1921 to 1925 these areas were gradually placed under the administration of Slovak clergy answerable directly to Rome. Relations between Czechoslovakia and the Holy See remained cordial until the end of the First Republic, aided by the successful celebrations in 1929 marking the millennium of the death of St Wenceslas. Marmaggi himself went on to assume the nunciature in Poland in 1928. The dispute over Hus was finally laid to rest in 1999, when Pope John Paul II, speaking on behalf of the Church he led, apologised for the unjust condemnation of the Czech theologian, describing him as a ‘reformer of the Church’.

The cohesion of Czechoslovakia was undermined by the asymmetry between its constituent parts. While the Czech lands were already highly industrialised in 1918, Slovakia remained predominantly an agricultural region. This disparity translated into differences in wealth.[31] Moreover, during the 1920s, Slovakia’s specialisation in agriculture was deliberately reinforced, further widening the industrial gap between these two parts of the country. It was only in the second half of the 1930s, in connection with national defence preparations, that efforts began to close this divide – a process that accelerated significantly during the Second World War. In the first decade after the war, disproportionately large amounts were allocated to industrial development in Slovakia – primarily in heavy industry – exceeding what would have been expected on the basis of its share of the population or national income.[32] The promotion of industrialisation in Slovakia was regarded as a key tenet of the policy aimed at equalising living standards across Czechoslovakia, thereby contributing to the country’s faster development and more harmonious functioning. The proportion of the Slovak population employed in industry increased from 14% in the 1950s to 36% three decades later. This shift was accompanied by an improved standard of living:[33] national income per capita in Slovakia, which had amounted to just 57% of the Czech figure in 1948, rose to 73% in 1960, 78% in 1970, and 85% in 1983.[34]

Although the disparity in wealth between Czechs and Slovaks was alleviated during the era of real socialism, it was never fully eliminated by the end of the shared state. One of the arguments raised in the political reform debate that began after democratisation in 1989 was the Czech reluctance to ‘continue subsidising Slovakia’. It is important to remember that these discussions took place amid rapid political transformation, during which real GDP per capita initially declined. The drop hit Slovakia much harder, as it was less prepared for the transition – real GDP per capita fell by 23% there between 1989 and 1992 (compared with 9% in the Czech lands and 13% in Poland).[35] As a result, the narrowing wealth gap seen at the end of the 1980s began to widen again in the early 1990s. Slovak real GDP, which in 1989 had stood at 91% of the Czech level, dropped to 77% by 1992.[36]

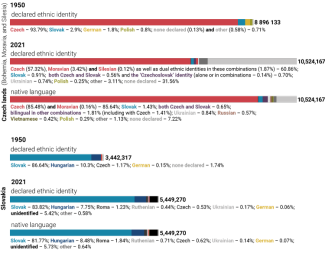

Czechs also outnumbered (and continue to outnumber) Slovaks. In 1918, there were more than three times as many Czechs as Slovaks in Czechoslovakia. Today, according to the 2021 population censuses in both countries, roughly twice as many people have Czech as their mother tongue as Slovak (see Charts 1, 8, and 9).

Czechoslovakia dissolved twice. The first dissolution occurred in 1939 as a result of the collapse of the Versailles order in Europe. The fragile Second Czechoslovak Republic did not survive for even half a year. By November 1938, owing to the Munich Agreement imposed by Germany, the First Vienna Award (regarding Hungary’s territorial claims), and the acceptance of an ultimatum from Poland (primarily concerning the Cieszyn Silesia region), the country had been stripped of 29% of its territory, 32% of its population, and around 40% of its industry. Although both Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia obtained autonomy within the reconfigured state, this paradoxically did not significantly improve interethnic relations. In the fluid and extremely complex international situation, mutual mistrust between the nations only deepened.

In autonomous Slovakia, the office of prime minister was assumed by Tiso. His party, the Hlinka Slovak People’s Party (HSĽS), dismantled political pluralism and began restricting civil rights. Amid a wave of anti-Czech sentiment, Czech teachers and administrative staff were expelled from Slovakia, often at the initiative of the ruling HSĽS. The party’s paramilitary wing, the Hlinka Guard, organised demonstrations against Jews (blaming them for the First Vienna Award) and, in the process, vandalised Jewish-owned shops and businesses. These actions foreshadowed the deportation of the Jewish population, which began in 1942. Over the course of the war, more than 70,000 Jews – approximately 80% of the Jewish population living in Slovakia in 1940 – were killed.

Relations between Czechoslovak President Emil Hácha and leading Slovak politicians were marked by significant tension. At a meeting in late 1938, Hácha accused them of seeking Slovak secession, a charge Tiso denied, even promising to exclude separatists from the Slovak government. However, by February 1939, during the formation of a new cabinet under the same leadership, the prime minister spoke extensively about building Slovak statehood and did not once mention Czechoslovakia. Hácha retaliated – in response to reports that Slovakia intended to declare independence on 10 March, he dismissed Tiso and his government the day before. On direct orders from Prague, Czechoslovak troops occupied Slovakia.