Sky-high ambitions of the Orbán government: Budapest’s air cargo boom

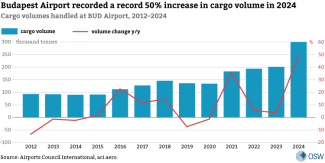

In recent years, Hungary has seen significant growth in air freight. In 2024, Budapest Ferenc Liszt International Airport handled nearly 300,000 tonnes of cargo, recording an annual increase of 50% and establishing itself as one of the key hubs in the region. Since 2018, the airport’s private operator has invested €80 million in developing cargo infrastructure, leading to the opening of the BUD Cargo City terminal in 2020. This expansion increased the airport’s handling capacity to 420,000 tonnes. In 2024, the airport was also partially renationalised, with the state regaining an 80% stake after almost two decades. In July 2024, the Ministry of National Economy announced plans to modernise and expand the facility through its co-owner, the French company VINCI Airports – one of the global leaders in airport management. This is expected to further boost efficiency, and according to recent reports, there are also plans under consideration to build a new cargo airport, which would become the largest such hub in the region.

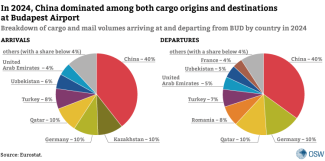

The Hungarian government has become increasingly explicit about its air transport ambitions. These are reflected in growing freight volumes, particularly from one direction: more than 40% of cargo arriving in Hungary originates in China. Budapest is becoming a key component of the emerging ‘Air Silk Road’ concept. However, further development of its role as a cargo hub will depend on EU–China trade relations and on Hungary’s ability to broaden the composition of handled cargo beyond the low-value segment.

Operations and infrastructure

Budapest Ferenc Liszt International Airport (IATA code: BUD) is Hungary’s most important airport. The country also has four significantly smaller facilities handling international traffic – in Debrecen (DEB), Sármellék (SOB), Pér (QGY) and Pécs (PEV). The capital’s airport is located around 16 km south-east of central Budapest, near the M0 ring road, which links the M1, M7, M6, M5, M4, M31, M3, and M2 motorways that extend in different directions across the country. Covering an area of 1515 hectares, it has two terminals and two runways, and its infrastructure enables it to accommodate and service wide-body and cargo aircraft. The airport serves as a base for Hungary’s private carrier Wizz Air – one of the major players in the low-cost airline market. It previously served the now-defunct national carrier Malév, which ceased operations after declaring bankruptcy in 2012. The airport is one of the region’s key transport hubs – it offers around 150 passenger connections to 49 countries and handles more than 80 cargo flights per week.

Freight is transported both as belly cargo (carried in the holds of passenger flights) and through dedicated cargo services operated by a wide range of carriers – the so-called integrators (courier companies offering door-to-door services), namely DHL, UPS, and FedEx, as well as airlines such as Qatar Airways Cargo, Turkish Airlines Cargo, Air China, Cargolux, China Cargo Airlines, Longhao Airlines, Sichuan Airlines, Hongkong Air Cargo, SF Airlines, YTO Airlines, Fly Meta, Ethiopian Airlines, China Southern, RomCargo, Atlas Air, Uzbekistan Airways, Georgian Airways, and Hungary Airlines. The absence of a national carrier and the liberalisation of the domestic aviation market allow foreign operators – including Chinese ones – free access to the airport. Hungary also benefits from bilateral agreements that enhance cargo operations by allowing for broader connection networks. The implementation of the Airport Cargo Community System (ACS) has digitised cargo handling operations, creating a platform accessible to all stakeholders in the supply chain – carriers, freight forwarders, ground handlers, and customs authorities. Although the majority of cargo processed at Budapest Airport consists of small e-commerce parcels, the airport is also working to gain the capabilities and certifications necessary to handle specialised goods, particularly those linked to domestic industrial production. Since 2021, it has held the CEIV Pharma certification issued by the International Air Transport Association (IATA), confirming compliance with standards for transporting pharmaceuticals. It is currently seeking CEIV Lithium Batteries certification, which would confirm its ability to handle electric vehicle battery components. No European airport has yet received this designation.

The airport is well connected not only to a dense road network – cargo transport is also facilitated by the nearby MAHART Container Center intermodal terminal, located adjacent to the airport, as well as by two similar terminals on the nearby Csepel Island: Rail Cargo Terminal – BILK and METRANS BUCS Terminal. Budapest’s potential as a regional hub is also recognised by logistics companies. The US firm UPS, for example, has opened a large logistics centre in the nearby town of Vecsés, while China’s Cainiao (which operates the Alibaba e-commerce platform) has designated Ferenc Liszt Airport as its principal European transport hub. To meet the needs of logistics operators, the airport’s operator began building a logistics base in September 2018 that would form an integral part of the airport. The BUD Cargo City project involved the creation of 21,600 m² of warehouse space, 11,000 m² of office space, and 32,000 m² of handling space, enabling the simultaneous servicing of two wide-body aircraft capable of carrying up to 130 tonnes of cargo (such as the Boeing 747).[1] Launched in 2020, the terminal was expanded three years later, increasing the airport’s annual capacity from 250,000 to 300,000 tonnes, and then in 2024 to 420,000 tonnes.

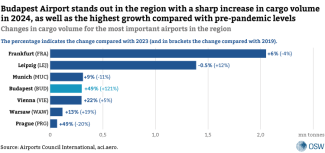

Hungary’s potential in a regional context

Budapest’s role is growing not only in cargo handling but also in passenger traffic. In both 2022 and 2024, Ferenc Liszt International Airport ranked first among European airports in the 15–25 million passenger category, according to the Airport Service Quality (ASQ) survey conducted by the Airports Council International (ACI), based on passenger feedback. In 2024, the Budapest airport handled 17.6 million passengers – a 20% year-on-year increase. In terms of passenger traffic, it does not lag far behind its regional competitors. That same year, Warsaw Chopin Airport served 21.3 million passengers (+15% year-on-year), while Václav Havel Airport in Prague handled 16.6 million (+18% year-on-year). However, the differences are far more pronounced when comparing freight volumes and the pace of growth in recent years.

In 2024, the airport handled 300,000 tonnes of cargo (70% of which were inbound shipments), marking a 49% increase compared with 2023. In contrast, Warsaw processed 117,000 tonnes (+13% year-on-year), although prior to the pandemic Budapest handled less cargo than Chopin Airport. Data from the first six months of 2025 indicate a further record year-on-year increase of 51%. When comparing Hungary’s air cargo potential with that of Poland, it is important to note that although Budapest Airport currently holds an advantage over Warsaw, the combined volume handled by Polish airports – particularly those in Rzeszów–Jasionka (39,000 tonnes in 2024),[2] Katowice–Pyrzowice (28,000 tonnes), Gdańsk–Rębiechowo (10,000 tonnes) and Wrocław–Strachowice (2,000 tonnes) – exceeds the total volume processed by Hungarian airports.

Figures showing a year-on-year increase in cargo volume of around 50%, and more than double that of the pre-pandemic period, are impressive not only in comparison with airports of similar size across the broader region. According to Rotate, an agency specialising in air cargo data analysis, the airport located near Budapest ranks 10th globally among the fastest-growing airports in terms of cargo volume – the only European airport to appear in the ranking.

Air cargo routes

Looking at the destinations and origins of air cargo to and from Hungary, China clearly dominates. In 2024, 40% of air cargo and mail arriving in Budapest came from Beijing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Changsha, Zhengzhou, Ezhou, Ningbo, Chongqing, Ürümqi, Chengdu, Shanghai, or Hong Kong. In turn, 35% of the cargo and mail dispatched from Ferenc Liszt International Airport was sent to one of these 12 cities.

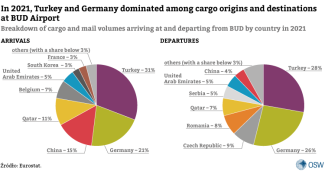

Among other air cargo routes in both directions, Germany’s high ranking comes as no surprise, given its status as Hungary’s main trading partner. Similarly, the significant shares of Turkey, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates are unsurprising, as their airports serve as major transport hubs in the Middle East. However, the notable presence of Kazakhstan (10% of arrivals) and Uzbekistan (6% of arrivals and 5% of departures) is less obvious. These countries are not among Hungary’s key trading partners – according to the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, their combined share of Hungary’s total foreign trade in 2024 was below 1%. Moreover, airports in Almaty, Astana, and Tashkent do not serve as major regional cargo hubs. This increased presence may be linked to the impact of economic sanctions on Russia. Both Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are part of a customs union with Russia, allowing them to facilitate transport between Russia and Hungary – a country that maintains good relations with the Kremlin. From Hungary, goods could then move further into the European market. Kazakhstan also plays an intermediary role in air cargo transport from China.

Comparable data from 2021 – before transport and trade restrictions were implemented – show that Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan did not appear as cargo origins and destinations for Hungary. Nor was China’s dominance as marked as it is today; it accounted for only 15% of outbound cargo and 4% of inbound cargo. At that time, Germany played a much larger role in both directions (21% outbound and 26% inbound), as did Turkey (31% outbound and 28% inbound).

The Chinese dragon lands in Budapest

The growing importance of China in Hungary’s air cargo sector in recent years reflects the close cooperation between Viktor Orbán’s government and Beijing in transport infrastructure and foreign direct investment. Since 2010, this cooperation has taken place under the banner of the ‘Opening up to the East’ policy, with Hungary becoming China’s largest partner in the region.[3] In 2015, Budapest became the first European capital to join the Belt and Road Initiative, under which China has launched a number of projects along the Danube to facilitate the flow of goods. These include the construction of the Budapest–Belgrade high-speed railway and the establishment of manufacturing and logistics facilities by Chinese technology and automotive firms such as Huawei, CATL, and BYD.

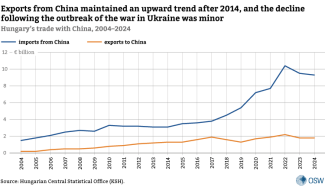

Before the full-scale war in Ukraine, Hungary was viewed as a country with the potential to become one of the key logistics hubs of the New Silk Road. This was due primarily to its strong rail connections with Adriatic seaports and the port of Piraeus, as well as the newly built East-West Gate intermodal terminal near the Ukrainian border. The facility has five pairs of tracks, enabling the simultaneous transfer of cargo from four 740-metre-long trains running on broad gauge to the European standard gauge.[4] However, the outbreak of war and EU sanctions on Russia and Belarus have limited the use of rail infrastructure. Routes linking Hungary with Russia are no longer available, and the only trains now arriving from China travel via the Middle Corridor. Since most cargo was previously transported by fast-growing maritime and air connections, the overall value of trade between Hungary and China has not declined after 2022 – although the trade balance remains heavily skewed in China’s favour.

The rapid development of air transport has been possible due to Hungary’s efforts, which have led to a series of agreements between Chinese airports and carriers and Ferenc Liszt International Airport. Regular delegations to China involving experts and trade diplomats, as well as the Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Péter Szijjártó, and the Minister for National Economy, Márton Nagy – both responsible within the government for relations with China – have helped Budapest airport multiply its cargo volumes in recent years. Currently, Budapest operates 37 direct cargo flights per week to cities across various regions of China, along with increased belly cargo transport now serving seven cities.[5] Direct connections of this kind are available to Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, and Ningbo, as well as Guangzhou and Xi’an (since June 2024), and Shenzhen (since August). This has brought the number of weekly flights between China and the Hungarian capital to 19, including seven from Shanghai and five from Beijing.

Source: author’s own analysis.

The high number of passenger flights is, of course, important for tourism and for supporting cargo transport. However, above all, it facilitates the continued development of business ties and provides essential logistical support for investments in Hungary – many of which involve the employment of Chinese labour. This is part of a broader framework of favourable conditions that the Hungarian state is seeking to establish to attract capital, often through significant concessions to China (such as the liberalisation of labour laws or environmental requirements). What makes locating factories in Hungary especially appealing to Beijing is the opportunity to avoid import tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles (and potentially on Chinese components, which are not yet subject to restrictions). This is particularly relevant in the context of possible anti-subsidy investigations and the imposition of additional duties on such vehicles. Another important factor in Hungary’s favour is the concentration of its automotive sector – including unhindered access to German car factories, which rely on Chinese components for electric vehicles – as well as the relatively low production costs compared with Western European countries.

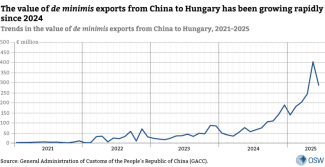

According to Eurostat, Hungary ranks among the top ten EU member states in terms of imports from China, and records the fastest growth rate. Electronic equipment and components for electric vehicles – particularly lithium-ion batteries imported from China – represent a key category by value. However, in terms of volume, low-value shipments dominate (under €150, falling within the EU’s de minimis threshold, which exempts them from customs duties). These account for around 40% of all goods arriving at Budapest Airport, approximately 90% of which are re-exported abroad. In value terms, this category has grown faster than total imports from China in recent years. In 2025, it experienced a pronounced boom – according to Chinese customs data, in May the value of de minimis goods reached a record high of over $400 million, reflecting the rapid expansion of Chinese e-commerce across the EU.

The sudden spike in de minimis exports from China to Hungary in May 2025 was partly a result of Washington’s decision to remove customs exemptions for shipments from China valued at under $800. This move by President Donald Trump aimed to reduce the presence of Chinese e-commerce platforms such as Temu, Shein, and Alibaba on the US market,[6] but it also had consequences for Europe. According to a report by Aevean, a consultancy specialising in the aviation sector, exports from such platforms to the US fell by 15% year-on-year between May and July 2025. A large share of these products was redirected to the European market, with Hungary emerging as the largest beneficiary of the tariff war, registering an annual volume increase of 21,000 tonnes.[7]

The conditions observed in global trade over the past few months have been particularly conducive for the inflow of Chinese air cargo into Hungary, thereby solidifying the country’s position as a European hub for e-commerce. The upward trend has been sustained, driven primarily by a growing number of air connections and the high level of activity by Chinese carriers at Budapest Airport. In 2024, a new player entered the market – Hungary Cargo Airlines – specialising in freight services for Chinese e-commerce platforms. The company had previously operated as the Hungarian commercial cargo carrier Universal Translink Airline Hungary, but more than half of its shares were acquired by Chinese businessman Wu Jiang, with control of the firm subsequently assumed by his compatriots.[8] As a state-owned entity, Air Hungary Szolgáltató Zrt. holds a 24.5% minority stake in the airline, and the company uses an Airbus freighter purchased by the Hungarian government. This led some domestic media outlets to report on the emergence of a new national carrier, although this claim is not reflected in the company’s ownership structure.

The government’s perspective: the sky is the limit

Ferenc Liszt International Airport was privatised under the Socialist government in 2005. At the time, 75% of its shares were acquired for €1.9 billion by the British company BAA International (which also operated Heathrow and Gatwick airports near London). Under the terms of the agreement, BAA obtained the right to manage the airport’s assets for 75 years. Fidesz, then in opposition, strongly objected to the move and made the repurchase of the airport one of its key campaign promises. In 2007, BAA sold its assets – with the consent of the Hungarian state and without any changes to the management agreement – to the international consortium Budapest Airport Zrt. This consortium consisted of the German airport investor AviAlliance (55.4%), the Singaporean investment fund Malton Investment (23.33%), and the Canadian pension fund Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (21.23%).

Following Fidesz’s landslide victory in the 2010 election – which gave Viktor Orbán’s party a two-thirds constitutional majority in parliament – the government began buying back previously privatised companies, most of which were in foreign ownership. The state-centric approach was reflected in increased government involvement in energy, banking, and telecommunications, under the slogan ‘strategic sectors in national hands.’ The government’s starting point was the belief that the existing economic model was in crisis and that the state should play a greater role, particularly as the guarantor of ‘economic sovereignty’ – acting not in the interest of multinational corporations, but in pursuit of the public good. In many cases, after reclaiming stakes, the state resold companies to domestic investors linked to the ruling party. Although the government successfully executed numerous major acquisitions (including the purchase of a stake in the energy giant MOL), it struggled for years to gain control of the airport. In fact, it completed the privatisation process in 2011 by selling the remaining 25% of shares – a surprise move justified by its limited influence over airport management due to its minority stake.

The plan to regain control of the airport had been postponed but has been revived in recent years. In June 2024, Viktor Orbán’s government announced the conclusion of over a year of negotiations for the purchase of shares in the consortium controlling Budapest airport. The state paid a total of €4 billion for an 80% stake in the holding, with the remaining shares going to co-investor, the French company VINCI Airports – one of the world’s largest private airport operators. The transaction was financed through the issuance of €1.75 billion in bonds. The Ministry for National Economy, which oversaw the takeover, framed the acquisition as a restoration of sovereignty after nearly two decades. In July 2024, Economy Minister Nagy announced plans to modernise and expand the airport in partnership with VINCI, with the aim of significantly boosting efficiency and ultimately transforming it into the largest transport hub in the region. Preliminary plans include the construction of a new terminal by 2032 and the expansion of the existing one. The government also decided to abolish the excess profit tax imposed on airlines (and seven other sectors of the economy) in mid-2022, which had earlier led to tensions between the Hungarian government and Ryanair. Its removal is expected to increase passenger traffic. The pro-government think tank Nézőpont estimated that existing investments in the airport would pay off within 25 years and that, by 2030, the airport will handle 30 million passengers annually.

The Orbán cabinet has also launched other initiatives aimed at stimulating air traffic. In June 2025, the Economy Minister confirmed the long-planned construction of a high-speed rail line connecting the capital to Ferenc Liszt Airport. The route will run between the airport and Kőbánya station and – unlike previous plans – will not only link the airport with the city centre but also integrate it into the national railway network. The minister also announced that, with Budapest Airport approaching its cargo capacity limit (approximately 450,000 tonnes), the government plans to build an entirely new cargo airport. Several locations outside the capital are under consideration. The facility could be developed using existing infrastructure or as a greenfield project. Key factors in the selection will include sufficient distance from residential areas (enabling night operations) and good connections to the transport network.

The total value of the two projects outlined above is estimated at around €2 billion. They would be carried out under a licence agreement by a foreign investor who has yet to be selected. According to Mr Nagy, a Chinese partner would be a logical choice, given that most cargo originates from China. From the perspective of the Hungarian authorities, it is crucial to ensure that the infrastructure and business environment are fully optimised for handling imports from China – particularly de minimis shipments from e-commerce platforms. According to data from the National Tax and Customs Administration (NÁV), 136 million low-value parcels underwent customs clearance in 2024, generating just over 40 billion forints (approximately €104 million) in VAT revenue for Hungary. For comparison, the total VAT revenue from imported goods amounted to 460 billion forints (roughly €1.20 billion), while customs duties generated 121 billion forints (around €314.6 million).

Summary and outlook

In 2024, Budapest Airport handled record cargo volumes, consolidating its position as a regional leader in air cargo and achieving results comparable to those of Munich and Vienna. The rapid growth in freight volumes – across dedicated freighters (so-called all-cargo services), courier companies (integrators) and belly cargo – has resulted from favourable structural conditions and an active state policy. The absence of a national carrier and a liberal regulatory framework provide broad market access for foreign airlines, while rapid infrastructure expansion and a growing number of connections have increased the airport’s attractiveness. A key role in this process has been played by the Hungarian government, which is pursuing a strategy to develop air cargo that is closely linked to enhancing trade relations with Beijing. The renationalisation of the airport and support through trade diplomacy fit into a broader model in which the state acts as a catalyst for growth.

Over the past two to three years, Ferenc Liszt Airport has become one of Europe’s main hubs for handling de minimis shipments from Chinese e-commerce platforms. Budapest has also benefited indirectly from trade tensions between the United States and China, which in 2025 contributed to the redirection of some cargo flows towards the EU market. Although lithium-ion batteries and electronics are also shipped to the Hungarian capital, in terms of tonnage the fastest-growing segment consists of low-value parcels sent by Temu, Shein, and AliExpress. This generates VAT revenue but not customs duties and, only to a limited extent, supports the development of advanced logistics services. This structure increases the model’s vulnerability to regulatory and political changes, particularly as it relies heavily on a single trade direction and a single type of cargo.

The Hungarian government has signalled an ambition to further strengthen cargo capacity. Following the completion of the airport’s renationalisation in 2024, plans were announced for its continued expansion and modernisation, the construction of a rail connection, and the creation of a new cargo terminal. The scale of the planned investments – estimated at around €2 billion – points to a long-term approach by the government but also raises the risk of overinvestment should demand weaken. If these projects are intended primarily to serve de minimis shipments from China, EU trade policy will be of critical importance. Any tightening of the approach to e-commerce from China or restrictions on the de minimis regime could quickly translate into a decline in cargo volumes in Budapest. In its current form, the Hungarian model remains highly effective in the short term, but its long-term stability depends on external factors and on its ability to diversify towards higher value-added cargo.

[1] The current warehouse space at Budapest Airport amounts to 40,000 m2 (by comparison, Warsaw Airport has 13,000 m2, which is set to increase to 26,000 m2 by the end of 2026).

[2] The performance of Rzeszów–Jasionka Airport is directly linked to the Russia–Ukraine war and to military transport operations.

[3] I. Gizińska, P. Uznańska, ‘China's European bridgehead. Hungary's dangerous relationship with Beijing’, OSW Commentary, no. 590, 12 April 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[4] J. Jakóbowski, K. Nieczypor, F. Tyszka, ‘Modernizacja suchego portu Záhony: węgierska próba przejęcia przewozów kolejowych z Chin’, OSW, 28 January 2021, osw.waw.pl.

[5] ‘Hungary operates seven direct flights from Budapest to Chinese cities’, About Hungary, 25 April 2024, abouthungary.hu.

[6] M. Kalwasiński, ‘Trade war 2.0. China responds to Donald Trump's tariffs’, OSW, 4 February 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[7] ‘US share of ex-China e-commerce declines to 15%, down from 31% in 2024’, Aevean, 21 August 2025, aevean.com.

[8] H. Siegmund, ‘Newcomer Hungary Airlines receives AOC’, CargoForwarder Global, 12 January 2025, cargoforwarder.eu.