The economies of the Baltic states: recession, stagnation and acceleration

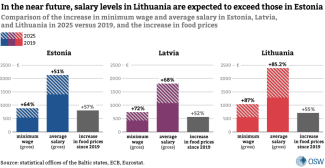

The economies of the Baltic states have in recent years experienced a series of shocks, triggered by the global pandemic and the outbreak of the full-scale war in Ukraine. Nearly four years of turbulence have led to a reshaping of regional economic relations. The long-standing view of Estonia as the fastest–growing and most advanced Baltic economy is gradually becoming outdated. A fourth consecutive year of recession, combined with the absence of an effective reform agenda, has rendered the country progressively less competitive. Lithuania has assumed the position of regional leader in terms of economic growth, modernisation, and the rising attractiveness of its labour market. Vilnius has successfully adapted to the changing circumstances, including by integrating its economy more closely with that of Poland. By contrast, Latvia – mired in stagnation and lacking comprehensive reforms – is emerging as the poorest of the three Baltic states. In the longer term, each of the region’s economies will require the implementation of a broad set of reforms: to restore growth trajectories in the case of Estonia and Latvia, and to sustain them in the case of Lithuania.

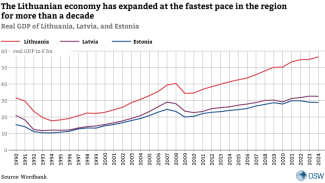

Over the past decade and a half, the economies of the three Baltic states expanded at broadly similar rates; however, from 2020 onwards, their growth trajectories have begun to diverge markedly. Lithuania has emerged as the frontrunner, with its real GDP increasing by 12.5% between 2019 and 2024, while Latvia recorded growth of approximately 7.6% over the same period. Estonia’s economy, by contrast, following a period of recession, is currently only 0.7% larger than in 2019.

Lithuania’s dynamic economic expansion has resulted in its GDP at current prices (2024) being almost twice as high as that recorded by Latvia and Estonia. These developments reflect not only the short-term shocks of recent years, but also the structural transformation of the Baltic states’ economies.

Difficulties in the north and acceleration in the south

The slowdown in the growth of the Estonian economy began in late 2021, with a sharp decline in economic activity persisting until the end of 2023, when GDP fell by approximately 3%.[1] In 2024, the negative trend began to ease gradually, with GDP declining by only 0.3%. Modest signs of recovery emerged only at the beginning of last year; however, despite growth in the first two quarters, the economy is unlikely to exit the phase of stagnation this year.[2] Estimates by the Bank of Estonia indicate that economic growth in 2025 will not exceed 0.6% of GDP.[3]

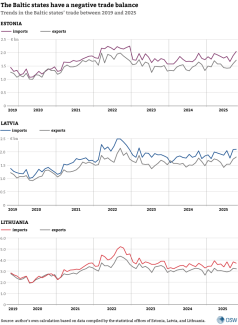

Estonia’s difficult economic situation is the result of a so-called ‘polycrisis’ triggered by the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and the full-scale war in Ukraine. The primary driver of the recession was a decline in exports, particularly to key trading partners, Sweden and Finland. According to data from Statistics Estonia, the total value of exports peaked in 2022 at €21.7 billion; since then, a pronounced decline has been recorded, with exports falling to €17.4 billion in 2024.

Domestic demand also remains weak, as Estonian households have curtailed consumption of goods in response to rising production costs, which have translated into higher prices.[4] This is a consequence of rising electricity tariffs and persistently high inflation, which reached approximately 20% in 2022, declined to 10% in 2023, and fell to just under 4% in 2024. An additional factor weighing on economic activity is the lack of coherence in the fiscal policy pursued by the government in Tallinn, manifested in successive – and often mutually offsetting – tax reforms. A prime example of this policy incoherence was the attempt to introduce a defence levy in December 2024. The legislation adopted at that time envisaged increases of 2 percentage points in VAT, corporate income tax, and personal income tax, to be implemented in stages: the VAT increase was to take effect in mid-2025, while the CIT and PIT rises were scheduled for 1 January 2026. Ultimately, the increases in personal and corporate income taxes were suspended in May 2025.[5] Vague and frequently changing regulations have also affected the taxation of internal combustion engine vehicles.[6]

Latvia is facing a similar, albeit less adverse, trajectory. Following the pandemic lockdown, the country recorded a strong economic rebound, with GDP growing by 4.8% in 2021. The slowdown coincided with the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. While the Latvian economy still recorded moderate growth in 2022 (1.8%), it has remained in stagnation since 2023, hovering on the brink of recession.

Against the backdrop of the other Baltic states, the Lithuanian economy has demonstrated markedly greater resilience to the long-term effects of successive crises over the past five years. Data from Lithuania’s national statistical office indicate uninterrupted growth, sustained even in the most challenging years for the region – 2020 and 2023 – when real GDP expanded at a rate of approximately 0.5%. In 2024, growth accelerated significantly, reaching 2.6% and exceeding earlier forecasts by 0.2 percentage points. From a medium-term perspective, this trend is likely to become entrenched, with growth in 2025 potentially reaching as much as 3%.

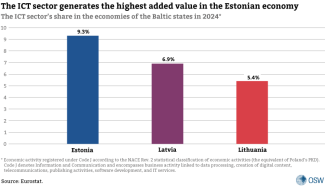

Several structural factors have contributed to the success of the Lithuanian economy. Of key importance have been greater sectoral diversity and the diversification of foreign trade. Lithuania’s economy is underpinned, among other sectors, by the chemical and petroleum industries (notably the refinery in Mažeikiai), as well as transport, financial services, and information and communications technology (ICT). By contrast, Estonia’s economic profile is narrower, with a stronger concentration on ICT, business services, and start-ups, while the timber and chemical industries play only a moderate role. Latvia, in turn, has developed sizeable financial services, transport, and ICT sectors, and also hosts smaller-scale metallurgical, food-processing, and mechanical engineering industries.

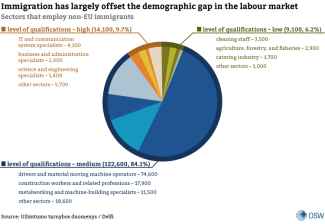

In recent years, Lithuania has effectively curtailed trade with Russia and Belarus, while simultaneously expanding its economic relations with partners within the European Union. The markets of Poland and Germany have gained particular importance, as demand for Lithuanian goods and services has risen in both countries.[7] Consequently, over the course of five years, Poland has replaced Russia as Lithuania’s most important trading partner. The relatively swift containment of inflation has helped to sustain steady levels of domestic consumption. At the same time, construction activity in the largest cities has expanded dynamically, while the labour market has remained stable, in part owing to inflows of migrants from Belarus, Ukraine, and Asian countries.[8]

The Lithuanian marathon

Unlike the other two Baltic states, Lithuania has achieved a significant infrastructural leap over the past decade, while Latvia and Estonia have relied to a greater extent on previously established drivers of growth – such as digitisation and transit – developed as recently as the late 1990s. A core element of Lithuania’s development strategy has been investment in transport infrastructure. Of particular importance has been the construction of a standard-gauge railway line from Kaunas to the Polish border, forming part of the Rail Baltica project. In parallel, road connections have been expanded as part of the Via Baltica corridor, with sections leading to the Polish border that were scheduled for completion in 2025. However, the most important measures have been those undertaken in the field of energy security, notably the development of electricity interconnections with Poland and the acquisition and expansion of the LNG terminal (FSRU) in Klaipėda,[9] which significantly enhanced the country’s energy independence.

Latvia’s development model, hitherto based on acting as an intermediary in trade between East and West, began to lose momentum in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (2008–2009). The three Latvian ports, connected by rail and pipeline infrastructure to Belarus and Russia, recorded steadily declining cargo volumes from year to year, and their economic significance continues to diminish. At the beginning of the previous decade, this sector accounted for approximately 10% of Latvia’s gross value added (GVA), compared with just under 6% at present.[10] Ultimately, this model collapsed following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine and the introduction of sanctions restricting trade with Russia.

Estonia’s growth engine, based on digitisation and the development of the IT sector, is also losing some of its competitiveness, although it remains the backbone of the Estonian economy. It is founded on the creation of advanced digital products competing in global markets (such as Bolt or Pipedrive), as well as solutions in the fields of cybersecurity and the digitisation of public administration. Exports of ICT services account for nearly one third of total exports of services in 2024, generate 9.3% of gross value added in the economy, and employ approximately 5% of the labour force (approximately 37,000 individuals). The Estonian ICT sector remains more advanced than its Lithuanian or Latvian counterparts, as it continues to rely to a greater extent on the development of proprietary solutions rather than on hosting the services of multinational corporations. In recent years, however, Lithuania’s communications technology, internet services, and high-tech sectors have been developing at an exceptionally rapid pace, thereby narrowing Estonia’s longstanding advantage.[11]

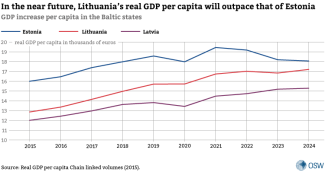

The prolonged recession in Estonia is contributing to the gradual emergence of the Lithuanian economy as the strongest in the region. Although Lithuania had already been nominally larger than the Estonian and Latvian economies, this was largely attributable to the size of its domestic market. Historically, Latvia and Estonia were regarded as more modern economies, as the processes of modernisation in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries reached them first, whereas Lithuania was characterised by a more peripheral profile, with a significant share of the agricultural sector.[12] At present, this trend is being reversed. Lithuania is witnessing rapid development in modern branches of the economy – such as cybersecurity, laser technologies, and biotechnology – including investments in high value-added technologies that until recently were largely the domain of Estonia.

The scale of this acceleration is substantial: in 2024, Lithuania’s nominal GDP reached a level equivalent to 98% of the combined size of the Estonian and Latvian economies, compared with approximately 80% a decade earlier.

A Lithuanian, a Latvian, or an Estonian – which is wealthier?

Lithuania’s faster economic growth and the likely attainment – or even surpassing – of Estonia’s net wage levels in 2025 will not automatically translate into greater societal prosperity. The populations of Lithuania and Latvia face a markedly more pronounced problem of income inequality than Estonia.[13] According to Eurostat data, income inequality in Estonia remains the lowest in the region and deviates from the European average by only 1 percentage point. In the other two Baltic states, the level of inequality is significantly higher, with Lithuania recording one of the highest rates in the European Union.[14]

Estonians also continue to be in a more favourable position in terms of the risk of poverty, with this indicator nearly 4 percentage points lower than in Lithuania.[15] Despite less favourable indicators of poverty and social stratification, wages in Lithuania nonetheless offer the greatest purchasing power.

The overall level of prosperity and quality of life remains highest in Estonia, despite the ongoing recession. According to the OECD Better Life Index (2023),[16] which compares 11 key aspects of well-being, Estonia continues to outperform Latvia and Lithuania. Similarly, the Human Development Index (HDI) developed by the United Nations, as well as its inequality-adjusted variant (IHDI), remain most favourable in Estonia.[17] However, the advantages over the other Baltic states that worked in its favour a decade ago are gradually diminishing; according to data from 2023, this trend is clearly visible.

Significant differences remain evident in individual components of the quality-of-life indicators compiled by Eurostat. In 2024, despite adverse economic trends, Estonia continued to record the lowest share of households experiencing difficulties in balancing their monthly budgets.[18]

Outlook: searching for new drivers of growth

Current trends suggest that the existing growth drivers of Latvia and Estonia have been exhausted and that both economies are in need of new ones. Long-term investment is also required in order to address the challenges they currently face. A common task for all three Baltic states is to boost productivity and maintain competitiveness in the face of rapidly rising labour costs. While this issue is of moderate importance at present, it is likely to intensify in the future.

The condition of the peripheral Baltic economies, which are based on a dependent development model, will be largely determined by economic developments in the larger states of the Baltic Sea region. In Estonia’s case, the pace of recovery will depend to a significant extent on the performance of the Finnish and Swedish economies, which in 2024 accounted for approximately 16% and 9% of Estonian exports, respectively. External influences on Latvia are less pronounced; nevertheless, the slowdown in Northern Europe also affects economic conditions there. An additional challenge for Latvia is the fact that it is currently becoming the poorest of the Baltic states.

The Lithuanian economy stands out from its Estonian and Latvian counterparts owing to a more diversified sectoral structure and a broader geographical distribution of development centres; unlike the other Baltic states, it is not concentrated in the capital region. Lithuania does not rely on a single dominant specialisation whose slowdown could lead to stagnation. Its current economic success stems from greater diversification and structural flexibility, as well as from the development of strong trade relations, primarily with Poland. In the coming years, this cooperation may prove decisive for the growth dynamics of the Lithuanian economy.

Lithuania’s success over the past five years should be viewed as a form of leapfrogging – an advance that has so far allowed it to circumvent problems that may affect the entire region in the near future. However, the existing growth drivers, based on exports, foreign investment, and labour cost competitiveness, are unlikely to deliver growth of the same intensity in the coming years as that recorded over the past three decades.

APPENDIX 1

APPENDIX 2

[1] K. Tabri, ‘The economy contracted by 3% last year’, Statistics Estonia, 1 March 2024, stat.ee.

[3] B. Oja, ‘Eesti Pank lükkas majanduskasvu ootuse uude aastasse’, ERR, 23 September 2025, err.ee.

[4] Eadem, ‘Jaekaubanduse müügimaht võttis augustis suuna alla’, ERR, 30 September 2025, err.ee.

[5] H. Wright, B. Oja, ‘Estonia scraps defense tax, makes VAT rise permanent’, ERR, 8 May 2025, err.ee.

[6] A. Whyte, K. Koppel, ‘Minister: Car tax in Estonia not likely to be abolished’, ERR, 17 September 2025, err.ee.

[7] D. Simėnas, ‘Lietuvos ekonomika 2024 m. išaugo 2,6%, pranokdama lūkesčius’, Verslo Žinios, 30 January 2025, vz.lt.

[8] In mid-2025, approximately 218,000 foreign nationals resided in Lithuania. Many originate from other former Soviet Republics, but there has also been an increase in the number of immigrants from countries such as India. ‘Migracijos departamentas: Lietuvoje šiuo metu gyvena 218 tūkst. užsieniečių’, Delfi, 23 January 2025, delfi.lt.

[9] ‘Symbol niezależności energetycznej Litwy: terminal LNG Independence w rękach państwa’, TVP Wilno, 6 December 2024, wilno.tvp.pl.

[10] J. Mauris, ‘Latvian transport sector. Long good-bye to the East-West transport corridor’, Macroeconomics, 20 May 2022, macroeconomics.lv.

[11] The Estonian ICT sector continues to rely more on developing new digital services rather than on providing support services.

[12] 25 years ago the agricultural sector employed up to 20% of the active workforce. Currently, this figure is below 5%.

[13] ‘People with a disability more likely to face poverty, social exclusion in Baltics’, Latvian Public Media (LSM), 19 August 2025, eng.lsm.lv.

[14] Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income, Eurostat, ec.europa.eu.

[15] Ibidem.

[16] Better life index, OECD, oecd.org.

[17] Human Development Index, UNDP, undp.org.

[18] Inability to make ends meet, Eurostat, ec.europa.eu.