Closing ranks: Russia-China energy cooperation amid escalating confrontation with the West

Cooperation in the energy sector, which has long been a key pillar of Russia-China economic relations, has assumed even greater importance since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. For the Kremlin, the sale of fossil fuels to China provides a vital source of foreign currency and, indirectly, of budget revenues. From Beijing’s perspective, these fuels offer a cheaper and more secure alternative to supplies from other directions. The prolonged lack of access to alternative markets for hydrocarbons has left Russia dependent on trade with China under unfavourable terms dictated by Beijing.

Despite the complementarity of their economies and the convergence of their strategic objectives, Russia and China face real obstacles to extending their energy cooperation. This is demonstrated by the decline in Russian oil exports to China following the imposition of US sanctions in 2025 and by the protracted negotiations over the Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline. The Kremlin’s desperation may be growing, but it has not yet abandoned its efforts to secure favourable pricing terms. At the same time, China is rapidly expanding its domestic energy sources and continues to diversify its foreign supplies, while maintaining caution in the face of new Western restrictions. Overcoming these limitations and taking further steps to strengthen energy cooperation would send a clear signal that China is adopting a more confrontational stance towards the West and that Russia is willing to accept its growing dependence on China as the de facto leader of the anti-Western bloc.

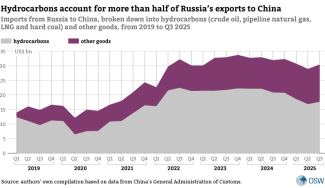

Fossil fuels as the cornerstone of bilateral trade

In 2024, the three key fossil fuels – crude oil, hard coal and natural gas (supplied via pipelines and as LNG) – accounted for two-thirds of Russia’s total exports to China, amounting to $85 billion.[1] Chinese purchases became a crucial source of funding for Russia’s war machine after most Western markets closed themselves off to its energy resources in late 2022. Since then, China has purchased nearly half of all Russian hydrocarbons sold abroad. India has also emerged as a major buyer, accounting for around one third of Russian oil exports. Without China’s willingness to increase its imports, Russia would have faced the need to make more substantial production cuts, affecting budget revenues, the financial performance of energy companies and the economy as a whole, as the so-called fuel and energy complex accounts for 20% of Russia’s GDP.[2] Moreover, in 2024, tax revenues from the extraction and export of resources by oil and gas companies[3] reached 11.1 trillion roubles, representing 31% of total federal budget income.

In the context of Russia’s rising spending on its war effort, maintaining a steady stream of export revenue is of vital importance to the Kremlin, particularly as it ensures the inflow of foreign currency. Taxing the energy sector also allows the government to avoid shifting the costs of the war directly onto the population. Fearing public discontent, it is seeking to mitigate the impact felt by Russian citizens.

However, it is important to note that the export of individual hydrocarbons differs in terms of their political and economic significance. Crude oil sales are an indispensable source of federal budget revenues, while gas exports carry substantial political weight since they can be used as a tool to exert pressure on third countries. In contrast, hard coal exports are relevant only from the perspective of that industry and a handful of Russian regions, generating limited profits.[4]

For China, Russia is the largest foreign source of fossil fuels, but Chinese energy imports remain diversified and their role is rapidly diminishing as the country advances its green transition. In 2024, crude oil, natural gas and hard coal imported from Russia accounted for 20%, 23% and 25% of China’s total imports of these resources, respectively. However, when domestic production is taken into account, Russian supplies covered only a small share of China’s overall demand, ranging from just a few to a dozen or so per cent.

Amid growing concerns over potential disruptions to maritime routes due to armed conflict and increasingly frequent shipping interruptions – from the ‘Ever Given’ incident in the Suez Canal to Houthi attacks in the Red Sea – overland routes are gaining prominence as more stable and secure alternatives to maritime transport, which is more vulnerable to hostile actions. However, the Chinese government’s priority is to expand domestic energy sources rather than to increase imports from the relatively reliable Russian direction. This policy reflects Beijing’s simultaneous pursuit of several objectives: enhancing self-sufficiency, accelerating technological development and industrial modernisation, and stimulating economic activity.[5] The electrification of additional sectors of the economy, including transport, combined with slower GDP growth in recent years, has reduced China’s demand for fossil fuels. Electricity, produced almost entirely from domestic sources such as coal and renewables, already accounts for around 30% of China’s final energy consumption, compared to just over 10% in the early 2000s. This share now exceeds that of both the United States and the European Union. The domestic production of fossil fuels is also steadily increasing, covering over 25% of China’s oil demand, around 60% of its gas needs and more than 90% of its coal consumption.

Oil – a strategic commodity for both sides

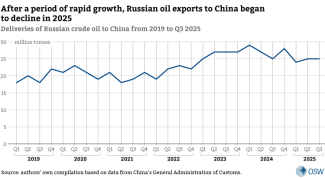

Crude oil is the most important component of Russia’s exports to China. In 2024, it accounted for 48% of the total value of Russian sales to the Chinese market, amounting to $62 billion. For Russia, the ability to sell crude oil in such volumes is invaluable, given the critical role of oil revenues in the federal budget. In 2024, taxes on oil extraction constituted 85% of all income generated by the oil and gas sector. The industry also contributes to the budget through other levies on its commercial activities; state-owned Rosneft is the single largest taxpayer to the federal budget.

Chinese buyers account for half the volume of Russia’s total crude oil exports. In 2024, sales of Russian oil to China reached nearly 2.2 million barrels per day. Based on Russia’s overall oil production, it can be estimated that nearly one in every four Russian barrels ends up on the Chinese market, either as crude or refined product. As with other commodities, the sharp increase in oil shipments came after Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and redirected a large share of its exports from Western markets to China. While in 2021 the volume of crude oil shipped to China stood at just under 80 million tonnes, by 2024 it had soared to 108.5 million tonnes.

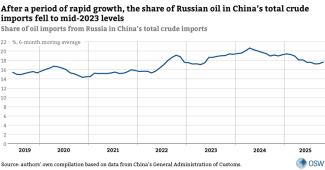

Although China ranks as the world’s fifth-largest oil producer, imports cover more than 70% of its demand. The country remains dependent on foreign supplies, but a strategy of diversification has helped it avoid excessive reliance on any single partner. In recent years, Russia has accounted for 15-20% of China’s oil imports; since 2023, it has been China’s largest supplier of crude. From Zhongnanhai’s perspective, this situation offers three main advantages. First, purchasing oil from Russia bolsters a China-friendly regime. Second, Russian supplies are relatively inexpensive due to Western sanctions. Third, they offer greater stability and security, as deliveries are primarily made through two overland routes (the ESPO pipeline linking Siberia with north-eastern China and a pipeline running through Kazakhstan) and port infrastructure in the Russian Far East, thereby avoiding the need to transit the Strait of Malacca or the Taiwan Strait.

Since the second quarter of 2024, Chinese customs data has shown a decline in crude oil imports from Russia, following two years of rapid growth. Initially, this drop coincided with a broader reduction in purchases from other sources, which had begun a few months earlier. However, since March 2025, deliveries from the rest of the world have seen a marked increase, while imports from Russia have risen only marginally. As a result, Russia’s share of China’s total crude imports fell from a peak of 20% in early 2024 to 17% in the third quarter of 2025. This decline was driven by two rounds of US sanctions, announced in January[6] and October . The latter targeted Russia’s two largest oil and fuel companies, Rosneft and Lukoil, prompting some Chinese buyers to suspend crude imports from Russia due to concerns over potential secondary sanctions.[7] It remains unclear how long this situation will persist.

As the sanctions regime imposed on Russia continues to tighten, the country is increasingly seeking to disguise the origin of its crude exports.[8] Some Russian oil may now be reaching China labelled as ‘Malaysian’ – that is, as a product originating from a country which for years has concealed the true origin of sanctioned barrels from Iran and Venezuela in its official trade statistics.[9] Imports from Malaysia surged at the turn of the first and second quarters of 2025, but in recent months they have been gradually displaced by shipments ‘from Indonesia’.

The volume of oil deliveries from Russia and other sources to China is ultimately determined by the current demand and the pace of strategic stockpiling. China’s oil consumption is expected to reach its peak around 2027 as a result of the accelerating electrification of its economy (including the widespread adoption of electric vehicles) and slower GDP growth.[10] In the following years, demand will mainly be sustained by the petrochemical sector. As in 2020, China took advantage of falling prices in 2025 to accelerate the build-up of its oil reserves. According to Bloomberg estimates, between January and August of this year, China purchased around 150 million barrels (worth approximately $10 billion)[11] in excess of immediate consumption; in the second quarter alone, it accounted for nearly 90% of the global increase in stockpiles.[12] This decision may have been driven by lower prices, growing concerns over supply disruptions and a desire to diversify reserve assets – in other words, to use oil as a partial alternative to US Treasuries.

Gas pipelines – a political signal with uncertain prospects

From a political standpoint, perhaps the most significant component of this energy relationship is the sale of Russian natural gas to China, as long-term contracts and the accompanying infrastructure projects will bind the two countries together for decades to come. For Gazprom, China represents the single most important export market, due to its capacity to take on large volumes of gas. The company redirected its gas supplies eastward as a necessary measure following the loss of its market share in Europe due to the Kremlin’s political decision.

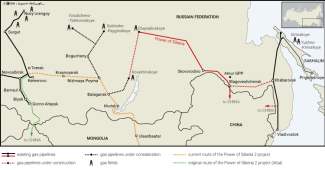

In 2024, China accounted for 35% of Gazprom’s total natural gas exports. These shipments have so far relied on the Power of Siberia 1 pipeline, which became operational in 2019 and reached its full capacity in 2024. According to forecasts, it will deliver around 40 bcm of gas to China in 2025. This volume is projected to increase by a further 10 bcm in 2027, when gas supplies from Sakhalin via the so-called Far Eastern route are scheduled to begin.

From an economic perspective, natural gas plays a smaller role in China than other fossil fuels. It accounts for just under 10% of primary energy supply, compared with over 50% for coal and nearly 20% for oil and petroleum products. It nevertheless serves an important function as a transitional fuel, replacing the most carbon-intensive sources in heating and industry and helping to stabilise the grid as the share of renewables increases. As a result, it improves the flexibility of the energy system, reduces emissions compared to coal-based generation and enhances energy security through diversified supply routes.

Domestic production meets around 60% of China’s gas demand. The remainder is imported either via pipelines (which accounted for 42% of imports in 2024) from Central Asia, Russia and Myanmar, or in liquefied form (58% in 2024), primarily from Australia, Qatar, Malaysia and Russia.[13] In 2024, Russia’s share of China’s pipeline imports reached nearly 40% (approximately 31 bcm). Gas delivered through the Power of Siberia 1 pipeline is the cheapest among all of China’s import routes. In addition, this overland logistical ‘arm’ shields gas supplies from potential disruptions that can affect maritime transport.

Map. Routes of gas pipelines from Russia to China

Source: ‘«Газпром» удваивает «Силу Сибири»‘, Коммерсантъ, 18 May 2020, kommersant.ru; gazprom.ru.

Russia has long been promoting the idea of further increasing gas export volumes to China. It aims to deliver future supplies primarily through the new Power of Siberia 2 pipeline with a planned capacity of 50 bcm/y. The project is intended to connect Chinese buyers with the West Siberian gas fields, which have so far primarily supplied the European market. Last September, Gazprom CEO Aleksei Miller announced that the two sides had signed a ‘legally binding memorandum’ concerning the pipeline, a step which he described as a breakthrough towards its construction. However, China is yet to officially confirm the existence of this document or to report any progress on the implementation of the project.

The concept of delivering gas from Western Siberia to China dates back to the late 1990s.[14] Despite the signing of several framework agreements, the two sides have so far failed to conclude a binding sales contract with a pricing formula, or to reach a decision on constructing the infrastructure and cost-sharing arrangements.[15] Estimates of the total cost of the project range from $13 billion to as much as $34 billion. However, it is worth noting that Power of Siberia 1, which is one-third shorter, may have finally cost as much as $60-70 billion, with the vast majority of that funding provided by Russia.[16]

Given Gazprom’s current negotiating position, which is far weaker than in previous years, it can be assumed that China is seeking to shift the full burden of the investment costs onto Russia, while also demanding a favourable pricing formula. In 2024, Russia sold gas to China via the existing Power of Siberia 1 pipeline at a price more than one-third lower than what European buyers were paying. According to media reports, China is now pushing to secure an even lower tariff for the new pipeline. Moreover, the fairly distant timeline for its commissioning (in the early 2030s at the earliest) further undermines the project’s profitability for Russia. Capitalising on Moscow’s limited room for manoeuvre, Beijing is effectively shifting the costs of future supplies onto its partner.

The terms of the contract would have to be exceptionally favourable to alleviate China’s concerns about increased dependence on a single supplier and the long-term sustainability of demand for Russian gas amid an advanced energy transition. Even assuming the full utilisation of Power of Siberia 2, total pipeline imports from Russia would reach around 100 bcm annually. Based on current forecasts that anticipate Chinese gas demand peaking at 600 bcm by 2040 and domestic production reaching approximately 310 bcm, Russia would account for a roughly 35% share of China’s gas imports and around 16% of its total consumption. While significant, these levels would not indicate an excessive dependence. However, these projections of demand may prove optimistic given the scale of China’s green energy transition. Rapid advances in electric vehicles, batteries and heat pumps, the fast-paced expansion of renewable energy sources and transmission infrastructure, as well as falling storage costs are all providing China with viable domestic alternatives to imported Russian gas.

The Russian statement regarding Power of Siberia 2, alongside the fact that China has not refuted the claim, should be seen primarily as a political signal directed at Washington. The mere announcement of the intention to build the pipeline has already affected the global gas market: potential new LNG projects aimed at supplying the Chinese market may be reconsidered in light of the prospect that Russian pipeline deliveries could meet China’s future demand. In this context, the actual implementation of Power of Siberia 2 would undermine the United States’ ‘energy dominance’, which is partly underpinned by its capacity to export domestic LNG and its strong presence in the global market. The US’s role in this area would be further diminished by the fact that the new pipeline, once operational, would likely enable Chinese companies to redirect LNG volumes from previously signed contracts to other countries and to compete directly with US suppliers in these markets.

Finally, the ongoing discussion around Power of Siberia 2 also serves as a symbolic indicator of the growing alignment between China and Russia that extends beyond the pursuit of mutual economic benefit. The prospect of concluding a long-term gas contract highlights the broad scope of the two partners’ potential and their willingness to act independently of Washington.

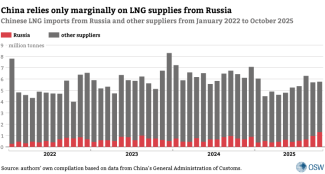

LNG – a test of the sanctions regime

Compared with crude oil and pipeline-delivered natural gas, LNG plays a much smaller role in Russia-China trade. In the first half of this year, China imported around 3 million tonnes of LNG from Russia, accounting for just under 10% of China’s total LNG imports and 21% of Russia’s LNG exports.

Russian LNG supplies serve as a supplementary source for China, with actual volumes governed by fluctuating demand. Liquefied gas makes it possible to engage in price arbitrage – purchasing cargo at a lower price and reselling it at a higher one – and to rapidly cover any seasonal or unexpected spikes in demand along China’s coastline. Moreover, LNG imports are not perceived as ‘binding’ due to their inherently flexible nature: suppliers can respond to shifting demand and are far less dependent on long-term contracts. Russia views LNG exports in a similar way: expanding domestic liquefaction capacity and the resulting sales represent an opportunity to reduce its dependence on existing infrastructure and overcome political constraints.[17]

In the face of the Western restrictions imposed on Russian LNG after 2022, cooperation between Russia and China in this area has become a test of the integrity of the sanctions regime particularly from Washington’s perspective. In August 2025, China decided to accept a shipment from Russia’s Arctic LNG 2 liquefaction plant, which has been under US sanctions since November 2023. These measures had effectively blocked exports from the facility, owned by the energy giant Novatek, as potential buyers refrained from purchasing its LNG due to fears of secondary sanctions.

Despite the restrictions, on 28 August 2025 a shipment from Arctic LNG 2 was unloaded for the first time at China’s Beihai terminal, operated by the state-owned company PipeChina. Notably, US sanctions also apply to the vessel itself – the LNG carrier Arctic Mulan. Under the US sanctions framework, the mere act of accepting this shipment should have triggered serious repercussions: any entity involved in the transaction should have been added to the sanctions lists. Although the market registered heightened risk associated with future operations at Beihai,[18] the US administration did not respond with any new measures or comment on the breach of its restrictions. This marks a notable shift in US approach to enforcing sanctions. Under President Joe Biden, the US Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) actively penalised LNG tankers involved in the transport of cargo from the facility.

China’s decision to accept a ‘toxic’ shipment at a domestic terminal can be interpreted as a test of the Trump administration’s willingness to enforce previously adopted sanctions measures. The political dimension of this move is underscored by its timing: it came shortly after the US-Russia summit in Anchorage. According to media reports, the two countries have been engaged in a dialogue on energy cooperation. Russia may have concluded that this opening reduced the likelihood of a firm US response to sanctions violations.

The absence of a US response raises the possibility that actions of this kind could lead to the emergence of a ‘corridor’ for transporting sanctioned LNG outside the Western financial system. This scenario is further supported by the fact that additional shipments from the Arctic LNG 2 project were unloaded at Beihai in September and October. Consequently, the facility could become primarily orientated towards supplying the Chinese market. If both production trains reach full operational capacity and year-round navigation is secured, China’s LNG imports could increase by over 10 million tonnes annually. A growing Russian LNG presence in China would also reduce the competitiveness of other suppliers, including those from the United States.

Conclusions: deepening ties as a challenge to the West

Enabling Russia to redirect a significant share of its fossil fuel exports to China after 2022 was not driven solely by economic considerations – it also served as a demonstration of Beijing’s support for Moscow. The consistently high volume of trade indicates that the two countries have partially succeeded in shielding this area of cooperation from the Western financial system. Developing supply routes and alternative payment methods is critically important for the energy security of both countries. Furthermore, it serves as a propaganda tool showcasing an emerging alternative to the West that also encompasses the economic domain.

The extent to which China and Russia will be willing to openly challenge the sanctions regime remains an open question. While they appear prepared to breach restrictions in the LNG sector, the situation may be different with regard to oil. In the past, US sanctions on Russian oil exports have complicated China’s ability to receive these supplies. The sanctions announced by the Trump administration in October 2025, which require third countries to limit their imports of Russian oil, and China’s subsequent response, may prove particularly telling in this regard.[19] However, whether these measures are implemented effectively and impose real costs on Chinese entities will depend on Washington’s resolve and the progress of its negotiations with both Moscow and Beijing.

Further steps to extend cooperation between China and Russia in this area – such as the actual launch of construction on the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, or regular violations of the sanctions related to the sale of Russian oil or LNG – would serve as an overt signal of the two countries’ hardening anti-Western stance. In particular, a decision to build a pipeline delivering gas to China from deposits traditionally supplying Europe would represent a major strategic move. Demonstrative actions aimed at undermining the Western sanctions regime would signal that China is decisively breaking with the EU and abandoning its efforts to weaken transatlantic ties to instead focus on consolidating the Chinese-Russian bloc in anticipation of a more intense confrontation with the US-led camp.

This analysis is part of the China-Russia Dashboard, a collaborative research effort of the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW), MERICS, and the Swedish National China Centre (NKK) and Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies (SCEEUS) at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs (UI). Explore the project here.

[1] The share of hydrocarbons in China’s imports from Russia declined in 2025, driven mainly by falling commodity prices, particularly crude oil.

[2] ‘Новак: доля ТЭК в ВВП России в 2024 году составила порядка 20%’, TASS, 30 January 2025, tass.ru.

[3] Although foreign sales are not taxed directly, fiscal revenues are closely tied to export volumes, as tax rates are calculated based on the export price.

[4] Despite the steady flow of coal from Russia to China, the authors of this commentary decided not to examine this sector, given the relatively limited importance of hard coal to the Russian economy and federal budget, particularly in comparison to crude oil. For a more detailed discussion, see: F. Rudnik, ‘Russian coal on the global market: difficulties and weak prospects’, OSW Commentary, no. 661, 23 April 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[5] See: M. Kalwasiński, ‘China on the road to ‘green’ energy security’, OSW Commentary, no. 605, 7 June 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[6] See: F. Rudnik, ‘Sanctions on Russia: the Biden administration’s parting blow’, OSW, 13 January 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[7] R. Wei Neo, S. Cheong, ‘Fear of Sanctions Stymies Russia-to-China Oil Flows for Now’, Bloomberg, 18 November 2025, bloomberg.com.

[8] T. Wilson, ‘The Iranian connection: how China is importing oil from Russia’, Financial Times, 20 August 2025, ft.com.

[9] S. Cheong et al., ‘The Clandestine Oil Shipping Hub Funneling Iranian Crude to China’, Bloomberg, 19 November 2024, bloomberg.com.

[10] ‘China oil demand to peak in 2027, up 100,000 bpd this year, state researcher says’, Reuters, 8 September 2025, reuters.com.

[11] China’s oil reserves are estimated at approximately 1.3 billion barrels, equivalent to nearly three months of domestic crude consumption.

[12] J. Blas, ‘Why is China stockpiling oil so much?’, Bloomberg, 18 September 2025, bloomberg.com.

[13] In the first nine months of 2025, the shares of LNG and pipeline gas in China’s imports were nearly equal. This was the result of expanded transmission capacity on the Power of Siberia 1 pipeline, combined with a 17% year-on-year decline in LNG imports.

[14] S. Kardaś, ‘The ‘new’ arrangements in Russian-Chinese energy cooperation’, OSW, 19 November 2014, osw.waw.pl.

[15] Speculation about progress on the project has been fuelled by reports that Gazprom is preparing to issue bonds in China and that a Chinese credit rating agency has awarded it an AAA rating, paving the way for the sale of securities denominated in renminbi. See: C. Leng, ‘China paves way for renminbi fundraising by Russian energy giants’, Financial Times, 7 September 2025, ft.com.

[16] S. Kardaś, ‘Wątła Siła Syberii: uruchomienie pierwszego gazociągu z Rosji do Chin’, OSW Commentary, no. 315, 5 December 2019, osw.waw.pl.

[17] F. Rudnik, ‘The effect of the sanctions: the Russian LNG sector’s problems’, OSW Commentary, no. 578, 7 March 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[18] ‘LNG market mulls potential fallout from Russian cargo discharge in China’, S&P Global, 1 September 2025, spglobal.com.

[19] F. Rudnik, I. Wiśniewska, ‘Trump’s first sanctions, the EU’s 19th sanctions package: the West increases the pressure on Russia’, OSW, 24 October 2025, osw.waw.pl.