Bosnia and Herzegovina in limbo: 30 years since the Dayton Agreement

Thirty years after the signing of the Dayton Agreement, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) remains a state mired in persistent institutional crises. The country’s existing political and constitutional model is a direct legacy of the constitution imposed during the Dayton negotiations. While the agreement brought long-awaited and lasting peace, it also established an exceptionally complex and inefficient system of governance. To date, all attempts to reform it have failed, as the ethno-nationalist elites have exploited the Dayton framework as a lucrative mechanism for appropriating state resources. As a result, three decades after the war, BiH remains a country whose genuine development continues to be obstructed by its own elites; it is also the least prepared candidate for EU membership. Moreover, nearly half of its citizens have emigrated.

Peace above all

On 21 November 1995, a peace agreement was negotiated at the US military base in Dayton, Ohio, bringing an end to the bloody three-and-a-half-year war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Earlier mediation efforts, undertaken from 1993 onwards, had failed to resolve the conflict. The international community intensified its engagement in response to the shocking events in the latter half of 1995 – the genocide in Srebrenica and the massacre at the Markale marketplace in Sarajevo. A turning point came in September of that year, when NATO's Deliberate Force operation effectively neutralised the Bosnian Serbs’ air defence systems, disrupted their main supply routes and destroyed key production facilities and arms depots. The shifting battlefield dynamics – particularly the retreat of Serb forces and the Croatian counteroffensive – paved the way for a ceasefire and the commencement of peace negotiations.

The United States was the principal initiator and host of the Dayton negotiations. Its objective was to bring the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina to an end and to develop a vision for a future Bosnian state in which the previously warring nations could coexist. US diplomacy undoubtedly succeeded in achieving the first of these objectives: ending a bloody conflict that had claimed more than 100,000 lives and displaced two million people, either as refugees or internally displaced persons. The NATO-led Implementation Force (IFOR) assumed responsibility for maintaining peace and implementing the military provisions of the Dayton Agreement. At its peak, it comprised as many as 60,000 troops, although its presence was gradually reduced over time.

The difficult process of state-building

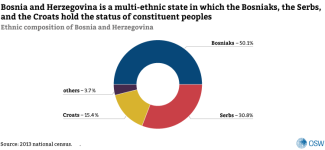

Implementing the vision of shared statehood proved far more challenging than enforcing the military component of the agreement. This largely stemmed from the divergent political objectives of the three constituent nations of Bosnia and Herzegovina – the Bosniaks, the Croats, and the Serbs. The civilian component of the agreement concerned the organisation and functioning of the state. These matters were primarily governed by Annex 4, which contained the text of the new constitution establishing a distinctive constitutional order. Critics of the Dayton Agreement focus particularly on this externally imposed constitution, arguing that it does not reflect the will of the citizens, as it has never been approved by any of BiH’s parliaments nor endorsed through a referendum. Moreover, the binding version of the document was drafted in English.[1]

The US negotiators envisaged the agreement as a temporary solution that would defuse ethnic tensions by separating the warring parties and lay the groundwork for Bosnia and Herzegovina to develop its own state institutions over time. From the outset of the Dayton negotiations, it was assumed that BiH would require international oversight on its path towards building a post-war order. This led to the establishment of the Office of the High Representative (OHR). Originally conceived as a monitoring and advisory body, the OHR’s mandate was expanded two years later due to insufficient progress in implementing the peace agreement and developing central institutions. It was granted the so-called Bonn Powers, which authorised successive representatives of the international community to take measures aimed at establishing the most basic attributes of statehood, such as a flag, a national anthem, a common currency, and vehicle registration plates.

As a result of this expansion of the High Representative’s powers, the first decade following the Dayton Agreement saw significant progress in building shared institutions, such as the Central Bank (established in 1997) and the Indirect Taxation Authority (2005). During this period, the central government acquired greater powers, expanding from only three ministries to nine – a number that remains unchanged to this day. The international community became deeply engaged in efforts to centralise the country’s security forces. Ten years after the war, the previously warring armies were merged into the Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina, placed under the authority of the central Ministry of Defence. A state-level Intelligence and Security Agency and a joint border police service were also created. While the police forces have not been fully unified,[2] the central State Investigation and Protection Agency (SIPA) has established itself as a trusted institution.

Attempts to reform the constitution

A decade after the agreement was signed, both international institutions and local elites came to recognise that the Dayton framework had entrenched an inefficient and dysfunctional system of governance that was incompatible with fundamental democratic standards. The Bosnian constitution explicitly favours members of the country’s three constituent peoples; in practice, this has reduced public life to matters of ethnic affiliation alone. Those who do not identify with any of these groups face systemic discrimination: for example, they are barred from running for the country’s highest public office.[3]

In 2004, the High Representative, Paddy Ashdown, articulated the need for profound reforms, stating that the country had to move beyond its ‘Dayton phase’ and enter a ‘Brussels phase’.[4] Two years later, efforts by the United States and the European Union led to the drafting of the so-called April Package – a set of constitutional amendments intended to strengthen the central institutions and significantly improve the functionality of the state. Despite months of negotiations among the main political parties, the proposal fell just two votes short of approval in parliament, preventing the adoption of what would have been the first major constitutional revision. In the years that followed, further attempts to reform the country’s political system were undertaken, but these proved equally unsuccessful.

In hindsight, the failure of the April Package had far-reaching consequences: it stalled reform efforts and diminished international engagement, particularly from the United States. As a result, local elites were effectively relieved of pressure to pursue any meaningful change.

The EU takes the helm amid rising separatism

A decade after the war ended, the United States handed over leadership in Bosnia and Herzegovina to the European Union. NATO’s mission was transformed into the EU-led operation EUFOR Althea, and the High Representative also assumed the role of EU Special Representative, although the two functions were later separated. At that time, the OHR’s priorities were primarily focused on BiH’s integration with the EU.[5] However, Brussels lacked both the necessary experience and a coherent vision to advance the demanding process of state-building. The EU’s institutions and member states operated under the prevailing assumption that the bloc’s enlargement policy, which had proved effective in Central Europe, would on its own provide sufficient incentive to push the country’s nationalist elites towards implementing painful reforms. This belief proved misguided: the changes required ran counter to the interests of those in power, who preferred to consolidate their grip by fuelling ethnic tensions rather than consistently steering the country towards EU membership. Over the course of three decades, the system has favoured the largest ethno-nationalist parties: the Croatian Democratic Union of BiH (HDZ BiH), the Serb Alliance of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD), and the Bosniak Party of Democratic Action (SDA).

Following earlier progress in state-building, separatist forces began to increasingly assert themselves within one of the country’s constituent entities – Republika Srpska. Initially a moderate and reform-minded figure, the Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik embarked on a campaign to weaken the central institutions, including the unified judiciary, armed forces, and tax system. The EU, fearing an escalation of tensions and haunted by the spectre of renewed conflict, repeatedly made concessions to the isolationist politician. Although some EU member states called for a firmer stance and punitive measures against Dodik, no EU-wide restrictions have ever been implemented, as Hungary and Croatia have in recent years used their veto power to shield the Bosnian Serb leader. The United States has adopted a different approach. In 2017, it imposed sanctions on Dodik for obstructing the implementation of the Dayton Agreement, later expanding these measures to include his associates, their family members, and affiliated companies.

As a result of Dodik’s actions, Bosnia and Herzegovina has failed to resolve key issues, such as the ownership of state property, or to implement the much-needed reform of the judiciary.[6] Meanwhile, Dodik has brought most of Republika Srpska’s institutions under his control, taken over the media, and suppressed civil society, while also becoming one of the wealthiest individuals in the country.

The separatist tendencies fuelled by the Bosnian Serb leader reached their climax in 2025, when he lost a court case over his refusal to comply with the decisions of the High Representative – an institution whose legitimacy and legal authority he has long contested. As a result, the former president of Republika Srpska was barred from holding public office.[7] His punishment represented an important indication of the state’s growing institutional maturity. Despite the ban, however, Dodik continues to exert significant influence over the politics of Republika Srpska, owing to his control of its institutions and media. He has become particularly active in the lead-up to the forthcoming elections for the entity’s highest office, effectively running the ongoing campaign; the SNSD’s official candidate remains entirely under his control. Dodik’s informal position has been further strengthened by the recent decision of the Donald Trump administration to remove him, his associates, and affiliated companies from the US sanctions list.

A tactical Serb–Croat alliance

Croat leaders have also fuelled centrifugal tendencies. Dodik’s separatist moves have inspired Dragan Čović, the head of the largest Bosnian Croat party, who has identified an opportunity to push for a revision of the country’s administrative structure. The preferred outcome for the Bosnian Croats, who share the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) with the Bosniaks, is either to divide this entity into two parts – one with a Bosniak majority and the other with a Croat majority – or to establish a ‘third entity’ as a separate unit within BiH. Earlier efforts to build Croat autonomy, particularly in the early 2000s, were opposed by the international community, which regarded such initiatives as incompatible with the Dayton Agreement.

Čović has adopted a different tactic from that used by Dodik: rather than open confrontation and threats of secession, he has relied on legal and institutional instruments, primarily by advocating electoral reform. HDZ BiH has called for changes to the method of electing the Croat member of the BiH Presidency; specifically, it seeks to create de facto separate electoral districts in which the Croats would constitute the majority of voters. Implementing such a mechanism would effectively fulfil their demand for a ‘third entity’, deepening ethnic divisions and reinforcing the overrepresentation of the Croat community, which comprises only around 15% of the population, but is allocated one-third of the seats in many key institutions. The Croats formally share the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina with the Bosniaks, yet they maintain a separate education system, their own media outlets, a postal service, and an energy distribution company serving Croat-majority areas. As part of their strategy to carve out a distinct unit, Croat leaders have also demanded full control over the planned gas interconnector with Croatia.[8]

Croatia has supported these efforts, citing its constitutional obligation to protect the rights of ethnic Croats living abroad. The Croatian leadership has leveraged the country’s membership in the EU and NATO to raise issues concerning the Bosnian Croats in both organisations.[9] Advocacy for the rights of compatriots in Bosnia and Herzegovina is a key element of domestic politics, helping to secure votes for the ruling HDZ. Croatia seeks to maintain its influence in Bosnia and Herzegovina, often impeding the integration of the Bosnian Croats into the state of which they are citizens. A telling example is a statement by the Croatian Foreign Minister, Gordan Grlić Radman, who has described the segregated education system in Bosnia and Herzegovina, known as ‘two schools under one roof’, as a good model of coexistence.[10]

Economic balance sheet

Despite a dysfunctional political system and repeated obstruction of reforms by local elites, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s economy has expanded significantly over the past three decades. It is important to note that the country embarked on a path of growth from a very low baseline compared with the other former Yugoslav republics, particularly those that remained at peace. The losses incurred during the Bosnian war were enormous. When the Dayton Agreement was signed in 1995, the country’s population was 23% smaller than just three and a half years earlier. The years of armed conflict caused industrial production to plummet by over 90%, while GDP per capita shrank by nearly 75% – from $1,900 in 1991 to around $500 in 1995.[11] According to World Bank estimates, direct war-related losses amounted to $15–20 billion.[12] However, the total cost of restoring production capacity, replacing lost national assets, and rebuilding infrastructure may have reached between $50 billion and $70 billion.[13]

The first post-Dayton years were marked by efforts to reconstruct the state with extensive international assistance. In 1998, Bosnia and Herzegovina introduced the convertible mark (BAM), initially pegged to the German mark and later to the euro. This arrangement has ensured nominal stability, but it has also limited the country’s capacity to respond flexibly to external shocks. During the 2008–09 global financial crisis, its GDP growth rate fell by 8.4 percentage points.[14]

As of 2024, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s GDP per capita was not far below that of other countries in the region, including those that had not experienced armed conflict. However, the country’s pace of growth could have been considerably higher had it not been for its flawed institutional system. The absence of a unified economic policy, disputes between the constituent entities, and regulatory discrepancies have hindered the functioning of the internal market and complicated the implementation of major foreign projects. Moreover, recurring tensions among political leaders continue to deter potential economic partners, who view Bosnia and Herzegovina as a high-risk investment environment.

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s economy is further burdened by an oversized bureaucracy. The public sector is bloated and inefficient, employing approximately 40% of all salaried workers.[15] Public sector wage expenditure, as a share of GDP, ranks among the highest in the world.[16]

On top of that, the country’s challenging demographic situation remains a serious constraint. Bosnia and Herzegovina is one of the fastest-depopulating countries in Europe, with nearly 50% of its citizens now living abroad. Emigration is driven not only by a substantial wage gap compared with Western countries, but also by non-economic factors such as inadequate education and healthcare systems, corruption, and the incompetence of the political elites. The mass exodus has imposed a tangible economic cost, contributing to a loss of up to 3% of GDP.[17]

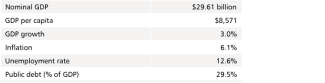

Table. Key economic indicators for Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2024

Source: The International Monetary Fund, imf.org.

A foggy path to Europe

Like the other Western Balkan countries, Bosnia and Herzegovina was promised a European perspective at the Thessaloniki Summit in 2003. However, it obtained candidate status only in December 2022, after nearly two decades of stagnation caused both by the country’s failure to implement reforms and by a deadlock in the EU’s enlargement process.

It was the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 that prompted the EU to revise its policy on admitting new members. As a result, Bosnia and Herzegovina was first granted candidate status and subsequently opened accession negotiations. Since then, however, it has made little progress on its path towards EU membership. According to the European Commission’s most recent reports, it remains the least prepared of all the candidate countries.[18]

The ongoing political crisis has made it impossible to implement the reforms required for EU accession. In early 2025, the central-level governing coalition – composed of the three Bosniak parties known as the ‘Troika’, HDZ BiH, and Dodik’s SNSD – collapsed owing to the SNSD’s obstruction of legislation required by the EU as part of the enlargement process, as well as the secessionist rhetoric and legal troubles of its leader. As the law does not provide for early general elections at the state level, the coalition has been paralysed since January. Consequently, progress on implementing EU integration-related reforms has stalled, and the country has lost access to part of its pre-accession funding.[19]

The future of the government remains uncertain. While the SNSD has signalled its willingness to return to the ‘European path’, the ‘Troika’ prefers to cooperate with three opposition parties from Republika Srpska that oppose Dodik’s policies. The situation is further complicated by the fact that the Bosnian Croat party remains in a tactical alliance with Dodik. Given the current political dynamics, the most likely scenario is the preservation of the status quo until the elections scheduled for October 2026.

Outlook

Despite the strong separatist tendencies of the past 30 years, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s statehood, for all its flaws, has become firmly established. Although the country continues to face major governance challenges, a clear majority of the population (74%) state that they are proud of their citizenship.[20] This contradicts the narrative promoted by Dodik, who claims that BiH is an ’impossible state that must break apart.’ At the same time, there is widespread recognition that the post-Dayton order has served political elites rather than ordinary citizens. In a 2022 survey, a striking 88% of respondents stated that the country’s constitution should be amended or completely rewritten, while over 70% expressed the view that the current constitution hinders the country’s development to a greater or lesser extent.[21]

However, comprehensive reform remains a distant prospect. It would require both the political will of the local elites and the active support of the international community. The mechanisms of consociational democracy enshrined in the country’s constitution are often used instrumentally, while fuelling ethnic tensions often serves as a substitute for genuine policy programmes and as a means of diverting attention from government failures, corruption, and abuses. Given the EU’s long-standing policy of concessions and the recent decision by the US administration to lift its sanctions against Dodik, systemic change in the country appears unlikely.

The status quo in Bosnia and Herzegovina is far from neutral, as it benefits leaders who pose a threat to the country’s cohesion. The prolonged political deadlock enables them to weaken the central institutions, normalises their secessionist rhetoric, and supports efforts to further undermine the constitutional order. While a full secession by Republika Srpska or an armed conflict still appear unlikely, the growing polarisation of the political landscape heightens the risk of incidents that could be exploited to inflame ethnic tensions and obstruct reform efforts.

APPENDIX

Specific characteristfics of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s constitutional system

Political system

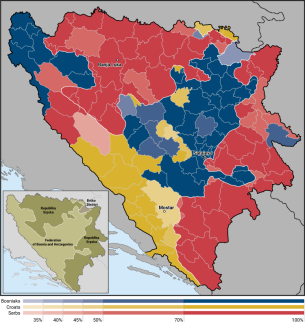

Bosnia and Herzegovina consists of two entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH), which is subdivided into 10 cantons, and the unitary, highly centralised Republika Srpska (RS). In addition, the Brčko District (BD) functions as a separate autonomous territorial unit owing to its strategic location, dividing RS into two parts and bordering Croatia.

The country operates under a three-tier system of governance: the state level (BiH), the entity level (FBiH and RS), and the cantonal level (applicable only in FBiH). At the state level, the highest office is the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which serves as a collective head of state composed of three members – one Bosniak, one Serb, and one Croat – directly elected for a four-year term. Legislative power rests with a bicameral parliament, while executive authority is vested in the Council of Ministers (comprising nine ministries), which exercises limited competences in areas such as foreign and security policy, fiscal and budgetary matters, and the judiciary. Most powers affecting the daily lives of citizens – particularly in education, healthcare, and infrastructure – are vested in the entity or cantonal authorities. Both entities, FBiH and RS, have their own presidents and bicameral parliaments. In the more decentralised FBiH, cantonal assemblies and governments also exercise specific powers.

One of the pillars of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s consociational democracy is the so-called principle of protecting vital national interests. In theory, it was intended to guarantee equality among the country’s three constituent peoples – the Bosniaks, the Serbs, and the Croats – but in practice, it has frequently been used to block political initiatives proposed by opponents.

The role of the international community

One of the defining features of political life in Bosnia and Herzegovina is the Office of the High Representative (OHR), which holds extensive legislative and executive powers. Established to oversee the civilian implementation of the Dayton Agreement, it was granted sweeping legislative and executive authority through the Bonn Powers adopted in 1997. These include the authority to dismiss domestic officials, enact legislation, and enforce its implementation. In addition, the Constitutional Court includes three foreign judges appointed by the European Court of Human Rights. Furthermore, the European Union’s EUFOR Althea military operation remains active in the country, tasked with maintaining internal security.

The main areas of dispute

- The structure of BiH. The Bosniaks (approximately 50% of the population) favour a centralised state. In the maximalist version, their demands include abolishing the territorial autonomy of RS and the cantons. The Bosnian Serbs (approximately 31%) seek the maximum degree of self-governance for RS. Recently, citing the concept of the ‘original Dayton’ which guaranteed broad autonomy for both entities, they have been campaigning to preserve the widest possible powers within RS, leading to boycotts of central institutions and disputes over property ownership. The Croats (approximately 15%) demand the broadest possible representation at all levels of government; in extreme cases, they have even called for establishing a third entity.

- The role of the international community. The Bosnian Serbs seek to end international oversight, notably by removing foreign judges from the Constitutional Court and abolishing the OHR.

- Politics of memory. Each of BiH’s three constituent peoples promotes its own interpretation of the events of the 1990s war, and frequently of the Second World War as well.

Map. Dominant ethnic groups by municipality in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Source: 2013 national census.

[1] S. Latal, ‘Sporazum u svom labirintu’ [in:] A. Kapetanović, J. Illerhues (ed.), Naslijeđe mira. Bosna i Hercegovina 20 godina poslije dejtonskog mirovnog sporazuma, Sarajevo 2015, pp. 19–33.

[2] Each entity has its own police force.

[3] This refers to the Sejdić-Finci case, which concerned the exclusion of citizens who do not belong to any of the country’s constituent peoples from running for the Presidency and the House of Peoples of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In its 2009 ruling, the European Court of Human Rights found this restriction discriminatory and required the state to implement reforms.

[4] T. Judah, ‘From Dayton To Brussels’, European Stability Initiative (ESI), 1 November 2005, esiweb.org.

[5] ‘Note of the Main Elements of the Dayton Agreement for Bosnia and Herzegovina’, The European Parliament, 28 September 2005, europarl.europa.eu.

[6] P. Wankiewicz-Kłoczko, ‘Dispute over the justice system in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, OSW, 12 February 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[7] P. Wankiewicz-Kłoczko, ‘The Dodik trial: a test of strength against Serb separatism in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, OSW, 6 March 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[8] P. Wankiewicz-Kłoczko, ‘Bosnia & Herzegovina: gas disputes along ethnic lines’, OSW, 6 April 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[9] B. Zawadewicz, ‘Pogróżki prezydenta Chorwacji dotyczące blokowania rozszerzenia NATO’, OSW, 17 May 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[10] On the subject of the so-called educational apartheid in Bosnia and Herzegovina, see: P. Wankiewicz-Kłoczko, ‘Historia służy polityce. Bośniacka szkoła była podzielona’, Nowa Europa Wschodnia, 21 October 2025, new.org.pl.

[11] A. Efendić, A. Hadžiahmetović, ‘Post-war economic transition in Bosnia and Herzegovina – A challenging transformation’ [in:] S. Keil, V. Perry (ed.), State-Building and democratization in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Ashgate, 2015, p. 109.

[12] Shaping a prosperous future for Bosnia and Herzegovina, The World Bank, 2024, thedocs.worldbank.org.

[13] G. Nedic, Financial and Technical Assistance in the Reconstruction and Development of Post-Conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina, The wiiw Balkan Observatory Working Paper, no. 73, September 2006, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, wiiw.ac.at.

[14] ‘GDP growth (annual %) - Bosnia and Herzegovina’, The World Bank, data.worldbank.org.

[15] ‘Improving Governance for Better Public Services in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, The World Bank, 16 May 2024, worldbank.org.

[16] Ibid.

[17] P. Wankiewicz-Kłoczko, ‘The vanishing Balkans. The region’s demographic crisis’, OSW Commentary, no. 647, 5 March 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[18] Bosnia and Herzegovina 2025 Report, The European Commission, 4 November 2025, enlargement.ec.europa.eu.

[19] P. Wankiewicz-Kłoczko, ‘Bosnia and Herzegovina’s European integration at an impasse’, OSW, 25 July 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[20] J. Kalenović-Đapo, J. Brkić-Šmigoc, Values in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Overview of the main findings of the 2019 European Values Study, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung BiH, Faculty of Philosophy in Sarajevo, 24 August 2020, library.fes.de.

[21] ‘Istraživanje: Šta građani i građanke misle o Ustavu BiH’, Građanke za ustavne promjene, 18 April 2022, gradjankezaustavnepromjene.wordpress.com.