Bosnia and Herzegovina’s European integration at an impasse

On 17 July, the European Commission informed the central government of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) that it would reduce the funding allocated under the EU’s Growth Plan for the Western Balkans. As a result, BiH has lost €108.4 million, which constitutes 10% of the amount initially earmarked for the country, though it may still receive up to €976.6 million. The Growth Plan is aimed at integrating the Western Balkans into the EU’s single market, deepening reforms and regional cooperation and boosting financial support to accelerate the region’s convergence with the EU. To receive these funds, whether in the form of grants or loans, countries must submit a comprehensive reform plan. The commission stated that if BiH fails to present such a plan by 30 September, it may lose a further 10% of the funds allocated under the plan.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is the only country in the region that has been unable to finalise its reform plan, owing to internal political tensions. Albania, Montenegro, Kosovo, North Macedonia and Serbia all managed to do so by the end of 2024. The ongoing paralysis of BiH’s central government could continue until the next elections scheduled for October 2026. Overcoming this deadlock will likely require pressure from the international community.

Commentary

- BiH remains mired in an institutional crisis that continues to stall its progress towards integration with the European Union. The enlargement process requires BiH’s authorities at all levels to harmonise domestic legislation with EU law – a demand that has faced strong resistance, particularly from Bosnian Serbs. Milorad Dodik, President of Republika Srpska (RS, one of BiH’s two constituent entities), opposes any reforms he views as leading to a greater centralisation of the country by shifting powers to the central government at RS’s expense. One of the main points of contention in the draft reform plan is the role of the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (see: ‘Dispute over the justice system in Bosnia and Herzegovina’). Brussels has called on the RS government to fill vacant judicial positions and implement the court’s rulings in the territory it governs. Political forces also remain divided on other key issues, including abolishing the veto rights of individual entities on the allocation of aid from the state (central) fund and aligning Bosnia’s visa regime with that of the EU.

- The constitutional framework established in Dayton continues to allow political actors to repeatedly paralyse BiH’s central government. The governing coalition at the central level included: three Bosniak parties known collectively as the ‘Troika’, the Croatian Democratic Union of BiH (HDZ BiH) and the Alliance of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD) led by Milorad Dodik. It collapsed earlier this year. The ‘Troika’ ended cooperation with the SNSD due to it obstructing legislation required by Brussels as part of the EU enlargement process. Another factor was Dodik’s secessionist rhetoric and legal troubles, including a first-instance conviction and an arrest warrant (see: ‘The Dodik trial: a test of strength against Serb separatism in Bosnia and Herzegovina’). Following an undisclosed agreement between Dodik, the central-level prosecution and the judiciary, the arrest warrant was withdrawn and the verdict of the second-instance court was postponed. The Bosnian media has speculated that Dodik could retire from politics in exchange for having his legal cases quietly dropped. The ‘Troika’ is now seeking to replace the SNSD in the coalition with three opposition parties from Republika Srpska, but the Bosnian Croats of HDZ BiH are opposed to this move. Dragan Čović, leader of the largest Croat party, remains in a tactical alliance with Dodik, seeing it as instrumental to achieving his own objective: a reform of BiH’s electoral law that would effectively result in the creation of a third, Croat entity and further deepen the country’s fragmentation.

- BiH’s lack of progress on its EU path reflects an impasse in the EU’s policy towards the country. BiH remains the least prepared EU candidate state; it has failed to make any significant progress in this regard since accession negotiations began in 2024. The EU has yet to devise a strategy capable of compelling the country’s ethno-nationalist elites to implement politically costly reforms that could ultimately drive them out of power. Another obstacle is the EU’s lack of consensus, particularly on the issue of imposing sanctions against Dodik, a deadlock that has prevented the bloc from exerting effective pressure on him. Hungary and Croatia are among the member states opposing punitive measures against this separatist leader of the Bosnian Serbs. As a result, the credibility of the enlargement process is eroding. The Bosnian population has historically been enthusiastic about joining the EU, but recently public support for accession has been falling: in 2024, 68% said they would vote in favour of the country’s EU membership, down from 76% in 2022. Moreover, according to IRI surveys conducted in 2022 and 2024, 42% of respondents now believe that the EU has no genuine intention of admitting the Western Balkan countries.

Appendix. The specific features of the political system in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) is a multi-ethnic state whose current political system was defined in the 1995 Dayton Agreement, which ended three and a half years of bloody civil war. BiH’s constitution, which is one of the annexes to this agreement, provides for a specific system of government based on the principles of territorial autonomy, ethnic parity and veto powers that can be used to defend the interests of the country’s individual nations.

The political system

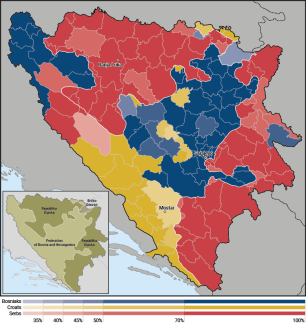

Bosnia and Herzegovina consists of two parts, the so-called entities: The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH), which is divided into 10 cantons, and the unitary and strongly centralised Republika Srpska (RS). The Brčko District is a separate, autonomous territorial unit due to its strategic location: it divides RS in half and borders Croatia.

There are three tiers of government in BiH: the centre (BiH), the entities (FBiH and RS) and the cantons (only in FBiH). At the central level, the highest office is the Presidency of BiH: this is the collective head of state, which consists of three representatives, one each for the Bosniaks, the Serbs and the Croats, who are elected for four-year terms in direct elections. At the central level, legislative power is vested in a bicameral parliament while executive power is exercised by the Council of Ministers, which has limited competences, mainly in foreign and security policy, fiscal and budgetary policy and the judiciary; it consists of nine ministries. Most of the powers relevant to the daily lives of people, that is those covering the areas of education, health care and infrastructure, are exercised at the entity level (RS and FBiH) or the cantonal level (in FBiH). Each of the two entities, FBiH and RS, also has its own president and a bicameral parliament; in the decentralised FBiH, assemblies and cantonal governments also exercise certain powers.

One of the pillars of the operation of consensual democracy in Bosnia and Herzegovina is the so-called principle of protecting vital national interests. In theory, it was supposed to ensure the equality of all the three constituent peoples in the country, the Bosniaks, the Serbs and the Croats; but in practice it has been used to block political initiatives undertaken by any given group’s opponents.

The role of the international community

One of the distinct features of political life in Bosnia and Herzegovina is the office of the High Representative (OHR), who has broad legislative and executive powers. His task is to implement the civilian provisions of the Dayton Agreement, while the ‘Bonn powers’ that were established in 1997 give him almost unlimited legislative and executive competences, including the power to dismiss officials in the country, enact legislation and enforce its implementation. In addition, the Constitutional Court includes three foreign judges who are appointed by the European Court of Human Rights. The European Union’s EUFOR Althea military operation also operates on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina with the goal of ensuring internal security in the country.

The main areas of dispute

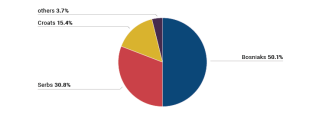

- The shape of Bosnia and Herzegovina: the Bosniaks (c. 50% of BiH’s population) support the idea of a centralised state (in the maximalist version, they call for the abolition of the territorial autonomy of RS and the cantons); the Bosnian Serbs (c. 31%) seek maximum self-governance for RS and have recently invoked the idea of the ‘original Dayton’, which guaranteed a high degree of independence for both entities, as they strive to maintain the broadest possible competences within RS: this has led to their boycotts of the central institutions and disputes over real estate; the Croats (c. 15%), for their part, demand the broadest possible representation at all levels of government, and in extreme cases, even the establishment of a third, Croatian entity.

- The role of the international community: the Bosnian Serbs call for an end to international oversight, including the removal of foreign judges from the Constitutional Court and the abolition of the OHR.

- Politics of memory: each of the three nations living in BiH nurtures its own attitude towards the events during the war of the 1990s, and often also towards World War II.

Chart. The ethnic structure of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Source: the 2013 census.

Map. Bosnia and Herzegovina: the dominant ethnic groups in individual municipalities

Source: the 2013 census.