A blow to Russia’s influence in Central Europe? US sanctions target Russia’s oil sector

The sanctions imposed by the United States on Russia’s two largest oil companies on 22 October carry significant consequences for those Central European countries that have maintained their energy ties to Russia. Although the EU has substantially reduced its imports of Russian oil since 2022, Slovakia and Hungary still obtain the majority of their crude from Russia, having secured exemptions from EU restrictions intended to grant them additional time to diversify. Russia’s Lukoil owns considerable assets in the region, including refineries in Bulgaria and Romania.

The US sanctions, along with forthcoming EU legislation aimed at further curtailing energy cooperation with Russia, have generated momentum for long-delayed efforts to increase supplies of non-Russian oil and to implement ownership changes. These measures could diminish Russia’s energy leverage, and consequently its political influence, in Central Europe. However, the determination of individual states to act in this regard varies significantly. In particular, Viktor Orbán’s government has been striving to delay the phaseout of Russian supplies and will only cease these imports if it is forced to do so. Therefore, the United States’ resolve in enforcing the sanctions will be a key factor.[1] Washington has already granted exemptions to Bulgaria (until April 2026) and Hungary, although the scope of the latter remains unclear.

The future of Russian oil assets in Bulgaria and Romania

In the Central European region, Russian capital has its strongest foothold in the oil refining sector in Bulgaria. Its most significant asset in the country is the refinery in Burgas – the largest facility of its kind in the Balkans, with a processing capacity of approximately 7 million tonnes of crude oil per year. It is also the only major refinery in Bulgaria, accounting for around 80% of the country’s fuel consumption. The facility is operated by Lukoil Neftochim Burgas, whose shareholders include Lukoil subsidiaries Litasco SA, registered in Switzerland (holding 89.97%), and Neftyanaya Kompaniya ‘Lukoil’ (with 9.88%). Lukoil Neftochim Burgas ranks first among Bulgarian companies in terms of revenue. It also controls more than 220 petrol stations and nine oil storage facilities within the Bulgarian market.

The traditionally strong position of Russian energy companies in Bulgaria has weakened markedly following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Since Russia suspended gas supplies in 2022, Bulgaria has secured its gas needs through long-term contracts with alternative suppliers, chiefly Azerbaijan, Greece, and Turkey. It has also taken steps to curb Lukoil’s dominance in the market. The company operating the refinery has lost its licence to use the Rosenets offshore oil terminal[2] (though it can continue to manage it in exchange for payments to the state) and has been hit with a 60% tax on its profits.

Under pressure from the Bulgarian government and EU sanctions (Bulgaria’s derogation expired in 2024), the refinery has also ceased imports of Russian crude; however, shipments of this crude may still be reaching the country via ‘shadow fleet’ vessels[3] and indirectly through Kazakhstan. The restrictions imposed on Lukoil have drawn criticism from segments of the Bulgarian political class, among them President Rumen Radev, who advocate maintaining energy cooperation with Russia. In 2024, Lukoil Neftochim Burgas reported its first loss in three years, amounting to €107 million.

In 2023, reports emerged of Lukoil’s attempts (so far unsuccessful) to sell its assets in Bulgaria under pressure from its government and the EU. Potential buyers reportedly included Hungary’s MOL, Kazakhstan’s KazMunayGas and, more recently, the Azerbaijani–Turkish consortium, including SOCAR and Cengiz Holding. In response to the US sanctions, the Bulgarian government established a state-appointed trust administration over the refinery to assume operational control and, under recent legislative amendments, to negotiate its sale. Washington has welcomed Bulgaria’s actions, granting four Lukoil subsidiaries operating in the country an exemption from the sanctions until 29 April 2026.

In Romania, Lukoil does not play as prominent a role as it does in Bulgaria, although its position within the country’s oil market remains notable. The company’s assets include the refinery in Ploiești, in which it holds approximately 99.8% of shares through Litasco SA, and a network of 320 petrol stations owned by Lukoil Romania SRL, which is wholly owned by Litasco SA. The refinery in Ploiești, one of four in the country, processes around 2.4 million tonnes of crude oil per year, accounting for roughly 20% of the market. Of the remaining three, two are owned by Rompetrol (controlled by Kazakh and Romanian capital), while the third belongs to the Romanian–Austrian company OMV Petrom. At the same time, the number of petrol stations owned by Lukoil makes it the second-largest operator in Romania’s retail fuel market, behind OMV Petrom, which operates around 500 stations.

Since 2022, the Russian oil giant has faced increasing pressure from the government in Bucharest, which has sought to reduce, or even eliminate, its presence in the market. The company has been excluded from public tenders, and the vast majority of institutions that previously sourced fuel from it – including the police and armed forces – have opted not to renew their contracts. Consequently, by late 2022 and early 2023, it began signalling its intention to sell its Romanian assets. Hungary’s MOL has reportedly expressed interest on several occasions, but no agreement has yet been reached. This apparent failure seems to have stemmed mainly from the Romanian government’s reluctance to transfer strategic assets to a company linked to the Hungarian state. Industry publications have frequently suggested that potential buyers could include KazMunayGas, Azerbaijan’s SOCAR, or Poland’s Orlen, although none of these companies have confirmed any such interest.

Lukoil’s attempts to sell its Romanian assets are complicated by the fact that they generate limited and unstable profits. Moreover, the Ploiești refinery is outdated and in need of investment. In recent years, the facility has frequently recorded substantial losses, amounting to €95 million in 2022 alone. Meanwhile, Lukoil Romania’s petrol station network posted a net loss of approximately €28.5 million in 2024.

The last strongholds of Russian oil in the EU: Slovakia and Hungary

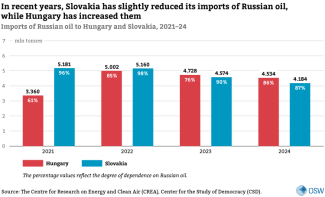

Hungary and Slovakia remain the only EU member states that continue to import Russian oil overland, owing to exemptions from the EU sanctions in force since 2023. Despite the EU’s policy of phasing out raw materials from Russia and the recurring disruptions to supplies via the Druzhba pipeline, both countries have been slow to diversify, striving to maintain imports from Russia at all costs. From the start of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine to the end of 2024, Russia delivered oil worth a total of €12.4 billion to Hungary and Slovakia. The two Central European countries are also connected in this sector through ownership ties: Slovakia’s largest oil company, Slovnaft, is owned by Hungary’s MOL.

Hungary is the only EU member state that has not merely failed to reduce its dependence on Russian oil imports since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, but has in fact increased it – from 61% in 2021 to 86% three years later. It has likewise maintained its reliance on Russian natural gas supplies. Taking advantage of the temporary exemption from EU sanctions, MOL continues to import crude oil from Russia via the southern branch of the Druzhba pipeline to supply its two refineries in Hungary and Slovakia, which require 8.1 million and 6.1 million tonnes per year, respectively. MOL and Lukoil have been cooperating since 2003; in 2019, they signed their most recent supply contract, which remained in force until the end of June 2025. The US-sanctioned Russian oil giant is currently supplying MOL with approximately 200,000 to 300,000 tonnes of crude oil per month. According to Argus, deliveries to the Százhalombatta and Bratislava refineries in Q4 2025 are estimated at 177,000 barrels per day.

Until mid-2024, Lukoil was the largest supplier of Russian oil to Hungary and Slovakia, accounting for roughly 40% of crude supplies and meeting approximately 30% of local demand. Its role has diminished since Ukraine imposed sanctions in June 2024, prohibiting the company from transiting oil through Ukrainian territory[4] and thereby forcing it to suspend deliveries via the Druzhba pipeline to both countries. MOL managed to maintain continuity of supply in two ways: by increasing purchases from other Russian suppliers (Tatneft and Rosneft) and by purchasing crude oil from Lukoil at the Ukrainian–Belarusian border, assuming responsibility for its transit across Ukraine. Short-lived supply disruptions also occurred in August 2025[5], when Ukrainian drones struck sections of the Druzhba infrastructure three times within a month, temporarily halting the flow of Russian oil to Hungary and Slovakia.

To date, the Hungarian government has not made any meaningful efforts to secure non-Russian oil. It has justified this by citing the country’s lack of direct access to the sea – despite Hungary’s connection to Croatia’s oil terminal – or by claiming that MOL’s refineries cannot be rapidly adapted to process other grades of crude, even though many European facilities have completed similar conversions within months. In 2022, MOL estimated that fully adapting its refinery near the Hungarian capital to process grades other than Urals would take between two and four years. According to its most recent statements, this process is now expected to continue until the end of 2026. This determination to maintain Russian supplies is also driven by price considerations. MOL has benefited from importing cheaper Russian oil, as sanctions have forced Russia to sell its crude at a discount relative to Brent – in October, the gap was nearly $12 per barrel. This has enabled the company to earn higher revenues than its regional competitors and gain a competitive edge. The Hungarian state budget has also benefited, as it receives revenue from a windfall tax levied on MOL’s profits.

In a sign that Hungary’s approach may be shifting, in October its government published a draft National Energy and Climate Plan, which explicitly identifies dependence on Russian oil imports as a risk that must be mitigated. This change in narrative is partly driven by the EU’s ongoing efforts to introduce legislation aimed at completely phasing out oil and gas imports from Russia. MOL has also indicated that Hungary should prepare for a possible interruption of supplies via the Druzhba pipeline. At the same time, however, the government continues to express its full commitment to maintaining energy cooperation with Russia and is exploring options to sustain the flow of Russian oil. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has openly criticised the sanctions imposed by the Trump administration on Russian oil companies; on 7 November, he travelled to Washington to request an exemption for Hungary. According to the Hungarian government, his talks with the US President resulted in a permanent derogation. However, both Western media reports citing White House sources and statements by US Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, indicate that the exemption was granted for one year. The US Treasury Department has yet to publish an official decision on this matter. Assuming that the latter scenario is accurate – which appears more likely given established US practice in similar cases – and taking into account the continued pressure from the EU, it is reasonable to conclude that Orbán’s visit to Washington did not yield a lasting solution. Consequently, Hungary will be compelled to take steps towards phasing out Russian oil.

For many years, Slovakia’s sole refinery – operated by Slovnaft, a subsidiary of the MOL Group – was supplied exclusively with Russian crude. As a result of measures implemented following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, this share fell to around 75% in 2024. The scheduled completion of adaptation works in 2026 is expected to significantly enhance the refinery’s ability to process crude from alternative sources. At present, the Bratislava refinery can allocate approximately half of its processing capacity to non-Russian oil. Russian crude supplies to Slovakia are delivered principally by two companies: Lukoil, which is now subject to new sanctions, and Tatneft, which remains unaffected. Temporary disruptions to Lukoil’s deliveries in 2024, resulting from Ukrainian sanctions[6], led to a sharp increase in Tatneft’s share of Slovnaft’s imports – from 53% in the first half of the year to 92% in July, according to Kommersant. The Slovak government has sought to postpone the phaseout of Russian oil while simultaneously preparing for such an eventuality. Prime Minister Robert Fico’s cabinet has suggested that efforts to secure derogations from US sanctions (according to Slovakia’s economy minister, the exemption negotiated by Hungary also applies to the Bratislava refinery owned by the MOL Group) may be linked to parallel talks with Washington on expanding the country’s nuclear energy sector. At the same time, the Slovak government has been lobbying the EU for a package of guarantees and compensation measures to offset the costs of eliminating all Russian hydrocarbons, as Slovakia continues to import also natural gas from Russia.

Alternative supply route via Croatia

Slovakia and Hungary have access to an alternative source of crude oil via the Adria pipeline, which connects them to the Omišalj oil terminal in Croatia. Until now, however, this route has been used only to a limited extent. MOL has signed several contracts for crude deliveries via the Adria pipeline – 2.2 million tonnes in 2023, 2.2 million tonnes in 2024, and 2.1 million tonnes in 2025 – but the actual volumes have been significantly lower: in 2023, they amounted to less than half of the contracted quantity. Long-standing disputes over MOL’s operations in Croatia, where it is the main shareholder in the local energy company INA, have negatively affected Croatian–Hungarian discussions on increasing oil flows. Hungary has criticised Croatia’s offer to expand oil deliveries to Hungary as ‘unreliable’, citing high prices and insufficient infrastructure capacity.[7]

The Croatian operator JANAF claims that the Adria pipeline can deliver between 13 and 16.4 million tonnes of crude oil to Hungary annually through the use of drag-reducing agents (DRA) – polymers that lower resistance during the flow of crude oil; the exact volume depends on the number of active pumps on each side of the pipeline. For comparison, the combined processing capacity of MOL’s refineries amounts to 14.2 million tonnes. However, in recent days, Fico has downplayed the importance of this route, stating that the full capacity of the pipeline has not yet been utilised on a regular basis (only test shipments have occurred) and that it remains unclear whether the pipeline can reliably meet the demand of countries located at the end of the supply route. In a further expression of Slovakia and Hungary’s long-standing distrust of Croatia, on 28 October Slovnaft publicly accused JANAF of suspending a delivery of 90,000 tonnes of crude oil for technical reasons, claiming that the interruption had ‘seriously jeopardised’ diversification efforts in Central Europe. JANAF rejected the accusation.

In light of the uncertain future of Russian oil supplies, Hungary has begun to demonstrate a somewhat stronger willingness to engage in talks with Croatia. At the same time, JANAF has shown increaseddetermination to expand crude oil deliveries to Hungary. US sanctions on Serbia’s NIS have forced JANAF to halt deliveries to the Pančevo refinery,[8] causing substantial losses for the Croatian pipeline operator, as transit to Serbia previously accounted for around 30–40% of its revenue. Increasing deliveries to Hungary is now seen as an opportunity to offset that shortfall. The Croatian government maintains that Hungary’s claims of inadequate pipeline capacity are unfounded; it has called for a new test of the Adria pipeline to be conducted in the presence of officials from MOL and the EU. The current contract expires on 31 December 2025, and negotiations on a new agreement are under way. Media reports have also suggested that MOL could acquire a minority stake in JANAF.

Outlook

The pace at which individual countries phase out their oil cooperation with Russia will primarily depend on how consistently the United States enforces its sanctions in this part of Europe. In some cases, such as its refusal to approve the sale of certain Lukoil assets to Gunvor, Washington has taken decisive action. In others, it has shown a willingness to make concessions: Hungary has already secured a promise of exemption from US restrictions. Regarding Hungary and Slovakia’s progress in reducing their dependence on Russian crude, a key factor will be the outcome of Hungarian–Croatian negotiations on increasing deliveries via the Adria pipeline to the refineries in Budapest and Bratislava.

US sanctions on Lukoil are likely to accelerate the sale of Russian assets in Bulgaria and Romania, although it remains unclear at this stage how this process will unfold. It is also possible that Romania will follow Bulgaria in securing a temporary derogation from the restrictions, similar to the arrangement applied to Russian holdings in refineries in Germany.[9]

At the same time, the example of Serbia shows that US exemptions are not open-ended and that inaction in this area can have serious consequences for the market. The determination of Central European countries to withdraw from energy cooperation with Russia will also be shaped by the progress of the EU’s legislative efforts aimed at fully phasing out imports of Russian hydrocarbons.

Map. Selected pipelines and refineries in Central European countries

Source: authors’ own compilation.

[1] I. Wiśniewska, F. Rudnik, ‘Trump’s first sanctions, the EU’s 19th sanctions package: the West increases the pressure on Russia’, OSW, 24 October 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[2] Ł. Kobeszko, F. Rudnik, ‘Bułgaria: ograniczanie rosyjskich wpływów w sektorze naftowym’, OSW, 28 July 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[3] This was revealed in an investigative report by Ukrainska Pravda. M. Tkach, ‘Russia continues to ship oil directly to the EU despite sanctions, investigation finds’, Ukrainska Pravda, 26 November 2024, pravda.com.ua/eng.

[4] OSW’s Central European Department, S. Matuszak, M. Menkiszak, ‘Hungarian-Slovak Dispute with Ukraine: Suspension of Lukoil Oil Supplies’, OSW, 26 July 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[5] ‘Pressure on Russia, pressure on Hungary: Ukrainian strikes on the Druzhba oil pipeline’, OSW, 27 August 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[6] OSW’s Central European Department, S. Matuszak, M. Menkiszak, ‘Hungarian-Slovak Dispute with Ukraine: Suspension of Lukoil Oil Supplies’, op. cit.

[7] I. Gizińska, P. Wankiewicz-Kłoczko, K. Dębiec, A. Sadecki, ‘Better from Russia than via Croatia: the future of oil supplies to Hungary and Slovakia’, OSW, 9 September 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[8] M. Szpala, F. Rudnik, ‘US sanctions against Serbian oil company NIS’, OSW, 21 October 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[9] M. Kędzierski, ‘Derogation of Rosneft’s German assets from US sanctions’, OSW, 30 October2025, osw.waw.pl.