Dialogue from a position of strength: China’s EU policy

The year 2025, marking the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the European Union and the People’s Republic of China, is also going down in the history of their mutual relations as the period when Beijing is exerting the greatest political and economic pressure on Europe. In April, China employed its strongest instrument of leverage to date – imposing export restrictions on rare earth metals and permanent magnets – and on 9 October it announced an unprecedented tightening of these regulations. China’s export controls may slow both the modernisation of Europe’s defence sector and the development of its industry. Furthermore, China continues to refuse to make concessions in the two main areas of dispute with the EU: its support for Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and its pursuit of an expansionist industrial policy that threatens the competitiveness of the European economy.

Consequently, despite the deterioration of transatlantic relations, the scope for cooperation between the EU and China is also narrowing and is becoming increasingly limited to specific areas. Although most EU member states share the assessment of the threats China poses, there is no consensus on concrete measures to counter them, which gives the issue a relatively low priority in the external policies of member states. This enables China to effectively exploit individual interests, foster divisions within the EU, and obstruct the initiatives of the European Commission – the main driving force behind the bloc’s assertive policy towards China.

Beijing is becoming increasingly convinced of Europe’s weakening international position. The return of Donald Trump to the White House, along with his critical stance towards the United States’ allies – including the European Union – has reinforced this perception. Although in recent months there have been signals suggesting a possible softening of China’s approach to Europe, the Chinese government has ultimately adopted a strategy based on projecting strength. Consequently, they show no readiness to make concessions on key contentious issues: their support for Russia’s war effort and their industrial policy undermining the EU’s competitiveness.

In the long term, EU–China relations are burdened by an ever-deepening strategic divergence – both in the security and economic dimensions. The assistance provided to Moscow holds fundamental importance in Beijing’s eyes: it believes that a Russian defeat in the war against Ukraine would inevitably lead to increased NATO pressure on China. Meanwhile, China’s export expansion[1] is a consequence of domestic overcapacity and weak internal demand. China seeks to ensure that foreign economies – including that of the EU – absorb the internal imbalances of its own economy. This poses the risk of displacing local production within the EU, increasing the trade deficit, and leading to higher unemployment and debt. Thus, by developing instruments to protect the EU market from Chinese pressure,[2] the European Commission under the leadership of Ursula von der Leyen has become a symbol of a more assertive policy towards China.Beijing has made the neutralisation of Europe’s role in the growing US–China rivalry its main political objective with regard to the continent. From its perspective, it is particularly important to prevent both the consolidation of NATO and the pursuit of a coherent transatlantic technological policy. In the short term, it seeks to avert Trump’s creation of a ‘cordon sanitaire against China’. To achieve this goal, the US intends to include provisions reflecting policies that run counter to Beijing’s interests in its bilateral and multilateral agreements with partners, including the EU. China’s main economic objectives towards Europe include maintaining broad access to the European market, which is vital for absorbing China’s industrial overcapacity. For this reason, the removal of tariffs on electric vehicles produced in China remains a symbolically important issue for Beijing in its relations with the EU.

China’s primary tools for achieving its objectives are economic and regulatory pressure on Europe. Beijing consistently instrumentalises existing economic interdependencies, using them to pit EU member states against one another, extract political concessions, and weaken the cohesion of the bloc’s policy towards China. Manifestations of this tactic include the introduction of export controls on rare earth metals and magnets, the initiation of anti-dumping and anti-subsidy proceedings, and the selective restriction of the access which European companies have to the Chinese market. China’s current policy towards the EU is characterised by increasing pressure and coercion, while the traditionally employed ‘charm offensive’ is on the wane.

Rare earths as a weapon

The strongest instrument of pressure so far which Beijing has used against the Western states – including the European Union – consists of export restrictions on rare earth metals and the permanent magnets produced from them. In this sphere, the world remains heavily dependent on China, which accounts for approximately 70% of global extraction and 90% of refining.[3] These substances are of critical importance to both the military sector (being used, among other applications, in radar systems, missile guidance, sensors, communications, and precision drives in advanced weaponry) and the civilian sector (including wind turbines, the automotive and electromobility industries, and consumer electronics).

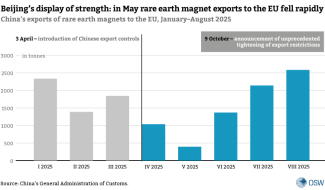

Since 4 April, seven of the 17 rare earth metals – samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium – along with permanent magnets, have been subject to export controls introduced by China’s Ministry of Commerce and General Administration of Customs. Under these regulations, sellers of such products are required to obtain licences from the state authorities. Among the requirements when applying for a licence information on the end user must be provided, as well as detailed data on the product’s intended use and technical specifications, a declaration confirming the non-military end use must be submitted, and the technical documentation must be shared. In this way, Beijing gains knowledge of the final use of the exported raw materials and retains the ability to control their destination, while at the same time potentially acquiring sensitive technological and commercial information. These controls are accompanied by an intensive campaign aimed at preventing the re-export of rare earth metals and permanent magnets by third countries (for example, South Korea, which holds reserves) to the defence sector – particularly that of the United States.[4]

On 9 October, China announced an unprecedented, extraterritorial tightening of the control regime. From December onwards, the requirement to obtain an export licence will apply to all products containing even trace amounts of rare earth metals of Chinese origin, or those produced using Chinese extraction and processing technologies. Earlier, from November, the list of metals subject to restrictions will be expanded to include holmium, erbium, thulium, europium, and ytterbium.[5] Under the new regulations, Chinese citizens will also be prohibited from participating in foreign projects related to the exploration, extraction and processing of rare earth metals or the production of magnets without prior government approval, in order to limit the transfer of knowledge abroad. The most serious consequences of the regulations concern defence: according to the announcement by China’s Ministry of Commerce, applications involving the use of rare earth metals and magnets in the military sector will be rejected.

In the past, China has repeatedly used export restrictions on rare earth metals as an instrument of pressure on foreign partners in matters it considers to be strategically important. It did so for the first time in 2010, when, following the escalation of a territorial dispute with Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, it limited the sale of these raw materials, formally citing environmental concerns. Between 2023 and 2025, Beijing systematically expanded its control over rare earth metals by introducing mandatory export reporting for gallium, germanium, antimony, graphite, tungsten and other elements. In 2023, it also banned the foreign sale of technology for the extraction and separation of these materials in order to slow the development of alternative supply chains outside China.[6]

The current situation differs from earlier ones both in scale and in the gravity of its consequences, as the new restrictions affect the entire European Union and encompass its strategic sectors, including defence and advanced industry. In the military sector, they may limit Europe’s ability to expand its defence capabilities – particularly in the context of the announced unprecedented increase in NATO member states’ defence spending to 5% of GDP by 2035.[7] Beijing has officially justified the introduction of the restrictions by citing the need to protect national security and interests, as well as to fulfil international obligations related to the prevention of weapons proliferation – emphasising that rare earth metals are widely used in the defence sector.[8]

In reality, however, these moves form part of a broader strategy of preventing the expansion of NATO’s military capabilities. China perceives this alliance as an instrument of US influence that could, in the future, be used in a potential confrontation in the Indo-Pacific region. Consequently, Beijing avoids actions that might contribute to strengthening NATO’s capabilities. In doing so, it supports Russia in its confrontation with the West and enables it to continue exerting military pressure on Europe.

In the industrial sphere, EU businesses – particularly German ones – have become the target of unprecedented pressure from China.[9] For example, in the automotive sector – which is already facing enormous competition from China, especially in the field of electromobility[10] – the export restrictions introduced in April led to significant disruptions in supply chains, resulting in the temporary suspension of production at some plants and assembly lines. As emphasised by the European Association of Automotive Suppliers,[11] between April and early June 2025, hundreds of applications for export licences were submitted to the Chinese authorities, but only approximately 25% of them were approved. EU companies assess the licensing process as non-transparent and inconsistent, because differences in how the regulations are enforced across Chinese provinces, together with unclear evaluation criteria, create regulatory uncertainty. Moreover, in some cases applicants are required to disclose information protected by intellectual property rights, which has raised serious concerns among European companies. The prolonged continuation of these practices could not only undermine the competitiveness of European industry but also affect the pace and cost of the EU’s energy transition, as the automotive sector – crucial to the development of electromobility – is one of the pillars of the green agenda.

The effects of the restrictions introduced in April are clearly visible in trade statistics: in March 2025, China exported 1,843 tonnes of permanent magnets made from rare earth metals to the EU, while in April – following Beijing’s introduction of the restrictions – exports fell by almost half (44%), to 1,035 tonnes, and then decreased further in May to 395 tonnes (down 62% compared with April). A rebound occurred in June (up 245% month-on-month, and 32% higher than in April), and by July foreign sales had returned to the levels recorded at the beginning of the year. Despite this improvement, the risk of another suspension or slowdown in licensing procedures remains realistic, meaning continued uncertainty for European industry over the supply of components essential for advanced manufacturing.

So far, in its relations with Europe, Beijing has mainly tested the effectiveness of economic coercion against individual states. The most illustrative example here is Lithuania, against which China applied unprecedented economic pressure following the opening of the Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius. The experience of that crisis – as well as the economic pressure from the United States during Trump’s first term – prompted the European Union to develop tools allowing a partial response to these actions, including the instrument to counter economic coercion by third countries. However, these mechanisms have not yet been used against China, even though it has introduced export restrictions on rare earth metals and magnets. This move would require a qualified majority vote in the EU Council, which – given the current divisions among member states, visible for instance during the debate on tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, and the rebound in rare earth metal and magnet imports – remains unlikely. Moreover, considering China’s global dominance in the rare earths market and the lack of easy alternatives, the EU, being too heavily dependent on supplies from China, is not currently in a position to respond by applying a ‘tit for tat’ approach. Instead, it is focusing on measures outlined since 2024 in the Critical Raw Materials Act: diversifying sources of supply, building up reserves, developing recycling, and investing in new technologies to reduce its dependence on third countries. Nevertheless, China’s export restrictions remain in force and may be used arbitrarily against the EU, depending on the prevailing political situation.

‘Divide and rule’ in a new version

Beijing continues to employ tried-and-tested instruments of influence against the European Union, basing its actions on the assumption that, if it wishes to gain concessions from Brussels, it needs to adopts a ‘divide and rule’ strategy, which involves exerting pressure on individual member states and mobilising European business circles that have significant economic interests in China or which are linked to the Chinese market, whether through exports or imports.

For China, three countries are currently the key players on the European stage: Germany, France and – more recently – Spain. It is pursuing a ‘carrot and stick’ policy towards them, focusing its pressure primarily on the industrial and agri-food sectors. It counts on these industries lobbying to persuade governments to soften the position of the European Commission, especially in three areas: 1) strategic – limiting the EU’s role in the US–China rivalry, 2) security – preventing NATO’s consolidation and the development of a coherent transatlantic technological policy, and 3) economic – maintaining broad access to the EU market for Chinese goods. In addition, China continues to cultivate its traditionally good relations with Hungary, which is becoming a key foothold for Chinese manufacturing investments within the EU,[12] although it is aware of Budapest’s limited influence on the mainstream of EU politics.

The German automotive industry, which is heavily dependent on the Chinese market, is suffering in particular due to the export restrictions on the rare earth metals and permanent magnets essential for production. Just before the EU–China summit in July, Beijing additionally lowered the threshold for classifying cars as luxury vehicles (entailing higher taxation), targeting German premium brands such as Mercedes-Benz (43% of the segment) and Porsche (18%). With France, it has employed a combination of pressure and concessions. On the one hand, it imposed five-year tariffs on brandy (chiefly French cognac) – widely interpreted as retaliation for EU tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs). On the other hand, it partially exempted some producers of this beverage from the higher tariffs on condition that they sell at an agreed minimum price. At the same time, China is actively expanding cooperation with France and Germany in advanced industry, including joint investments in battery technologies and technological partnerships with European automotive companies.

The Spanish agri-food sector, meanwhile, became the target of Chinese pressure ahead of the EU vote on tariffs on EVs from that country. As part of a series of anti-dumping and anti-subsidy investigations, pork (a key Spanish export to China) was also included. At the same time – as part of balancing these pressures – Beijing signed two trade protocols with Madrid concerning the sale of new product categories, including pork stomachs and cherries. Consequently, Spain abstained from voting on the tariffs, while Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez became the first European leader to visit China after the Trump administration tightened the customs policy in April 2025. The cases of Germany, France and Spain show that Beijing tailors its instruments of pressure according to the economic sensitivities of individual member states, but pursues a single goal – to weaken the cohesion of the EU’s position towards China.

At the political level, China is likewise pursuing a two-track policy towards the European Union, combining formal institutional channels with intensive bilateral diplomacy. Foreign Minister Wang Yi combined the high-level EU–China dialogue held in Brussels in June with his visits to Berlin and Paris, clearly demonstrating where Beijing sees its levers of influence. Nevertheless, in order to balance its pressure with gestures of goodwill – it lifted the sanctions imposed in 2021 on former MEPs. These actions, however, remain purely tactical and do not indicate any real willingness on China’s part to make concessions on key issues. Its policy towards the EU is evolving in a more assertive direction – marked by growing pressure and coercive measures, and diminishing incentives.

Beijing is calling Europe’s bluff

The EU–China summit in July became a unique test for the European Commission’s assertive agenda towards Beijing, promoted by President von der Leyen. The attitude of the Chinese authorities was demonstratively cool: the event was moved from Brussels to Beijing due to Xi Jinping’s reluctance to travel to Europe (even though he had made a four-day visit to Moscow in May), and its format was shortened from two days to one. In addition, the Chinese media emphasised that the Xi–von der Leyen–Costa meeting took place before the official start of the talks, signalling a downgrading of the event’s importance (since 2020, Xi had regularly taken part in EU–China summits).

China’s approach to the summit reflects its open hostility towards the EU’s assertive agenda – which includes the introduction of protective mechanisms such as de-risking,[13] the anti-coercion instrument[14] and tariffs on Chinese-made electric vehicles[15] – as well as towards von der Leyen herself, whom the Chinese press portrays as an executor of US policy.[16] Beijing consistently avoided discussing the effects of its own industrial policy on the EU’s single market, particularly on sectors that are strategically important for the bloc’s green transition, such as electric vehicles, photovoltaics, and lithium-ion batteries. It limited its position to calls for the organisation to remain open to exports from China. In this context, Xi’s statement during the summit about the need for Europe to make ‘the right strategic choices’, along with Premier Li Qiang’s assertion that cooperation with China is ‘the only correct choice’, represent attempts to divert attention from the structural disputes in EU–China relations and to suggest that the EU should abandon its hard line towards Beijing amid growing uncertainty about the future of transatlantic relations under Trump.

Xi did not make a single direct reference to the war in Ukraine, merely issuing a general call for dialogue and for ‘addressing both the symptoms and the root causes of problems’ (倡导标本兼治). In doing so, he indirectly echoed the Russian narrative, which places the responsibility for the conflict on Western states.[17] Moreover, immediately after the summit, Beijing announced the introduction of countersanctions against two Lithuanian banks – UAB Urbo Bankas and AB Mano Bankas – in response to the EU’s decision to impose restrictions on two Chinese financial institutions (Heihe Rural Commercial Bank and Suifenhe Rural Commercial Bank) under the 18th sanctions package. This move was a signal that China is also making a ‘tit for tat’ response in the context of the war in Ukraine.

The meeting confirmed the absence of room for compromise, as the parties did not issue a joint final communiqué, and the only agreed document was a joint press statement on climate cooperation, prepared in connection with the 30th UN Climate Change Conference.

European dilemmas

The deadlock in EU–China relations seen during the summit raises the question for Europe of how to shape its relationship with China when the latter conducts dialogue from a position of strength. China today feels it has the upper hand over the West: in its view, the export controls on rare earth metals and magnets – which have proved an effective tool of pressure even against Trump – confirm the effectiveness of its coercive policy. This further reinforces the conviction among the Chinese authorities that Europe, weakened by the war in Ukraine and by transatlantic tensions, has found itself in a particularly difficult position.

Europe’s first step towards adapting to the current circumstances should be to recognise that the nature of Beijing’s relationship with the EU has fundamentally changed. China can no longer be viewed merely as a place of cheap production and an attractive market, but must be treated as a threat in both industrial and security terms. The second step is to acknowledge that Beijing actively engages in lobbying selected sectors – such as agri-food and automotive – to influence EU policy on China. Therefore, it should be assumed that the short-term interests of individual industries may conflict with the long-term interests of member states and of the EU as a whole. The third step is to recognise that, in the security sphere, China stands on the opposite side to Europe – through its supply of dual-use products, purchases of Russian raw materials, diplomatic support for Moscow, and acceptance of its attempts to undermine the existing international security architecture.[18] The perception of these three fundamental issues still varies among the member states, and achieving consensus on them is a necessary condition for developing a coherent and effective EU policy towards China.

The starting point for conducting an effective policy towards China is to recognise that disputes in the two main areas – security and industrial policy – stem from Beijing’s long-term strategic objectives, which the EU can neither change nor ignore. These objectives are clearly subordinated to the logic of preparing for a confrontation with the United States – both through support for Russia and through an expansionist industrial policy. Under these conditions, only limited, issue-specific cooperation between the EU and China remains possible, for example in the fields of non-proliferation and preventing Russia’s use of nuclear weapons, or in supporting the return of Ukrainian children abducted by Russia. However, these initiatives carry inherent risks: Beijing participates in dialogue but avoids formal commitments, treating it primarily as a tool for portraying itself as a champion of peace, while failing to exert any real pressure on Russia.

In the industrial sphere, it would be a constructive solution for Chinese companies to invest in manufacturing plants in Europe – essentially on the basis of EU regulations requiring that the largest possible share of supply chains be located on EU territory. No regulations of this kind have yet been adopted, although their creation is a prerequisite for reducing the risk of the EU market being further flooded with Chinese production surpluses. This approach, however, requires that Europe should not be reduced to the role of an assembly base for Chinese products, but should instead acquire technologies – just as China drew them from Europe in previous decades.

[1] M. Kalwasiński, ‘A two-speed economy. China on the eve of a trade war’, OSW, 12 March 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[2] P. Uznańska, ‘De-risking in low gear. The way forward for the EU’s economic security agenda’, OSW, 26 January 2024, osw.waw.pl; idem, ‘Right of retaliation: the EU rolls out a tool to protect itself against economic blackmail’, OSW, 12 December 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[3] Mineral Commodity Summaries 2025, U.S. Geological Survey, 31 January 2025, pubs.usgs.gov.

[4] ‘China pledges concrete measures to prevent illegal outflow of strategic minerals’, Xinhua News Agency, 13 May 2025, english.scio.gov.cn; R. Arcesati, A. Junusova, ‘Beijing’s rare-earths export licensing system: delays by design?’, Mercator Institute for China Studies, 1 October 2025, merics.org.

[5] ‘商务部公告2025第61号 公布对境外相关稀土物项实施出口管制的决定’ (Communiqué by the Ministry of Commerce no. 61 from 2025: Decision on the introduction of control of the export of rare earth metals abroad), Ministry of Commerce and General Administration of Customs of the People’s Republic of China, 9 October 2025, mofcom.gov.cn.

[6] ‘商务部 海关总署商务部 海关总署公告2023年第23号 关于对镓、锗相关物项实施出口管制的公告 公告2023年第23号 关于对镓、锗相关物项实施出口管制的公告’ (Communiqué no. 23 from 2023 by the Ministry of Commerce and General Administration of Customs on the introduction of export control of goods containing gallium and germanium), Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, 3 July 2023, exportcontrol.mofcom.gov.cn.

[7] P. Szymański, J. Gotkowska, ‘NATO summit in The Hague: Trump’s return and a two-component 5% of GDP on defence’, OSW Commentary, no. 675, 26 June 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[8] ‘商务部 海关总署公告2025年第18号 公布对部分中重稀土相关物项实施出口管制的决定’ (Communiqué by the General Administration of Customs no. 18 from 2025: Decision on the introduction of export control of some goods linked to medium and heavy rare eath elements), op. cit.

[9] A. Kozaczyńska, ‘At the monopolist’s mercy: Germany’s dependence on Chinese rare earth elements’, OSW Commentary, no. 692, 6 October 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[10] S. Płóciennik, ‘Fear of retaliation: Germany’s concerns about punitive tariffs on electric cars from China’, OSW Commentary, no. 568, 5 February 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[11] ‘Urgent action needed as China’s export restrictions on rare earths disrupt European automotive supply chains’, CLEPA, 4 April 2025, clepa.eu.

[12] I. Gizińska, P. Uznańska, ‘China’s European bridgehead. Hungary’s dangerous relationship with Beijing’, OSW Commentary, no. 590, 12 April 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[13] P. Uznańska, ‘De-risking in low gear. The way forward for the EU’s economic security agenda’, OSW, 26 January 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[14] Idem, ‘Right of retaliation: the EU rolls out a tool to protect itself against economic blackmail’, OSW, 12 December 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[16] ‘Von der Leyen's 'de-risking' not a pragmatic approach to Europe-China relations’, Global Times, 2 April 2023, globaltimes.cn.

[17] ‘Ukraine was just the beginning. Russia’s REAL reason behind the war’, OSW, 5 February 2024, youtube.com.

[18] ‘China-Russia Dashboard: a special relationship in facts and figures’, Mercator Institute for China Studies, merics.org.