Parliamentary elections in the Czech Republic: Babiš on the verge of returning to power

ANO, the party led by the oligarch and former Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, is the clear frontrunner in the upcoming elections to the Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Republic, scheduled for 3–4 October. Since ANO is likely to be an indispensable partner in any post-election parliamentary majority, a coalition built around the party is expected to replace the centre-right government of Petr Fiala, which has been in office since late 2021. Should Babiš form an alliance with extremist parties, the new cabinet would likely focus on domestic policy, including increases in social spending. In foreign affairs, ANO has promised to adopt a more assertive stance towards the EU while maintaining a clearly pro-Western orientation. The Czech Republic is likely to step back from its role as one of the key providers of assistance to Ukraine, but it will remain sympathetic towards that country in its war against Russia.

One of the key factors that will influence the outcome of the elections is whether the ruling centre-right parties will be able to mobilise their former electorate, which has become disillusioned with the current government, particularly after it broke its promise not to raise taxes. These parties do not face any major challengers, but a significant share of their supporters, though unlikely to vote for the opposition, may choose to stay at home on election day. As a result, the ruling camp has focused its campaign on reactivating this voter base, with billboard slogans claiming that ‘everything is at stake’ in the upcoming elections.

The international dimension

The elections to the Chamber of Deputies will determine whether the Czech Republic remains at the forefront of efforts to support Ukraine and maintains its openness to refugees from that country. Even before Russia’s full-scale invasion, the centre-right had pledged a tougher stance towards the Kremlin; after the war broke out, the Czech Republic, alongside Poland, was among the first countries to send tanks and attack helicopters to Ukraine.[1] The Czech government also launched the so-called ammunition initiative with the aim of uniting and coordinating Western efforts to speed up deliveries of artillery shells to the Ukrainian army.

At the same time, the Czech Republic’s hospitality towards Ukrainian refugees has resulted in the highest number of Ukrainian arrivals per capita among the EU member states – 35 per 1,000 inhabitants.[2] On the one hand, this has reinforced public awareness of the reality of war in a country that does not directly border the conflict zone. On the other, it has exacerbated tensions, for example in the housing market. This has led to seemingly contradictory polling results regarding attitudes towards Ukraine and Ukrainians: a majority of Czech citizens support taking in more refugees, but they also believe that their country has admitted more than it can manage.[3] The Czech Republic is also the EU member state with the highest proportion of residents opposing Ukraine’s accession to the EU – 64 per cent, including 40 per cent ‘strongly’ opposed to this prospect.[4]

As public sentiment continues to shift, support for Ukraine and Ukrainians has emerged as one of the central issues of the election campaign. The government, drawing on Václav Havel’s foreign policy legacy,[5] emphasises that the country is standing ‘on the right side’. It also argues that this position has generated additional benefits in the form of contracts for domestic arms manufacturers and the prospect of Czech companies participating in Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction. In addition, the country’s strained labour market has benefited from a new source of labour through the influx of refugees.

The opposition, for its part, insists that the state should primarily focus its efforts on its own citizens. ANO, which is topping the polls at 30.5–33 per cent, has expressed this demand in a softer form, stressing the need to increase social spending for Czech citizens while also promising ‘zero tolerance for illegal migration’. Its leader has drawn on the ‘America First’ slogan, at one point even wearing a red cap similar to Trump’s, bearing the inscription ‘Strong Czechia’. Figures from the far-right alliance running on the ticket of Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD), currently polling at 10–14 per cent, have used much harsher language, pledging to deny ‘foreigners’ access to any benefits and to review residence permits for Ukrainian nationals.

Contrary to the alarmist rhetoric of the ruling camp, the Czech Republic’s foreign policy orientation is unlikely to undergo any fundamental change after the elections, although the country’s policy towards Russia and China will probably become more passive. Members of ANO, led by Babiš, have insisted that accepting the country’s continued membership in the EU and NATO is the ‘red line’ in their talks with potential coalition partners. This is a signal to prospective allies, namely SPD, which has called for a referendum on EU membership, and the communist-led alliance (Stačilo!, meaning ‘Enough!’, polling at 6–9 per cent), which also wants to ask citizens about whether the country should remain a member of NATO. SPD has already begun preparing its voters for a climbdown, admitting that under current conditions its demand should be seen as unrealistic. Beyond the political context (ANO’s opposition), another obstacle to its plans is the need to adopt a so-called constitutional law enabling such a referendum (the legal and in particular the constitutional aspects are discussed in more detail below). In an effort to increase the party’s chances of entering government, SPD officials have even suggested nominating ‘experts’ as ministers instead of their own highly controversial activists.

An ANO-led government would probably scale back assistance to Ukraine and adopt a more confrontational stance towards mainstream policies in Brussels. Babiš has repeatedly criticised the ammunition initiative and has called for pursuing more narrowly defined Czech interests under a ‘pragmatic’ foreign policy.

In this spirit, he has condemned the current government’s anti-Chinese gestures as an unnecessary risk to the interests of Czech companies. He has also promised to place greater emphasis on economic diplomacy. At the same time, although his party’s election programme describes NATO as the key to ensuring the country’s security, his pledge to ‘support diplomatic efforts aimed at ending the war in Ukraine’ may signal an alignment with the policies pursued by Hungary and Slovakia. These two countries have typically used similar language to dilute initiatives aimed at supporting Ukraine.

Babiš’s relationship with Donald Trump can be described as ambivalent. The Czech politician has long sought to emulate the US leader and placed hopes in his efforts to mediate an end to the Russia-Ukraine war. He even used to call himself a ‘Trumpist’, but now he opposes the US president’s trade policy and insists he could persuade him that expecting NATO members to allocate 5 per cent of their GDP to defence is a fantasy.

In the EU arena, the Czech Republic will oppose the Green Deal more forcefully and place greater emphasis on migration issues. At the same time, the former prime minister’s plans to revive Visegrad cooperation may fail in the face of the gradual disintegration of the V4’s political dimension and the lack of prospects for agreements on sensitive issues dividing its members, notably their stance towards Russia.

On the other hand, the future Czech government can be expected to improve relations with neighbouring Slovakia – currently experiencing one of its worst periods since the dissolution of the common state – and with Hungary, governed by Fidesz, which belongs to the same European political family.[6] The new cabinet may take inspiration from some of these countries’ controversial domestic policies. One issue that has repeatedly surfaced in the Czech election campaign is the risk of curtailing the relatively high degree of autonomy that public media currently enjoy from politics. However, the strength of the country’s institutions and civil society should constrain any excessive ambitions of the future ruling camp in this respect.

‘Bread and circuses’

The ongoing campaign has been largely dominated by social issues linked to a sharp rise in the cost of living. This was felt most acutely in 2022, but in the following year the purchasing power of wages continued to decline year-on-year in every quarter. At that time, Fiala’s cabinet was slow to introduce compensation measures in response to soaring food and energy prices; the solutions it eventually implemented proved relatively modest. The overall situation has improved in 2024–25, though progress has been uneven across different groups of employees. For example, trade unions have highlighted the relative impoverishment of a significant share of public sector staff. The education sector provides the clearest example of this decline: between 2021 and 2024, teachers’ salaries fell relative to the average wage from 126 to 109 per cent, while those of non-teaching staff dropped from 69 to 63 per cent.

As a result, each of the main opposition forces – including the left-liberal Czech Pirate Party (now polling at 7–10 per cent), which left the ruling coalition a year ago[7] – placed proposals to raise citizens’ living standards at the very heart of their election programmes. Since 2022, Babiš has repeatedly described the current government as ‘anti-social’, pledging measures to reduce food, energy, and housing prices. He has also promised pay rises for teachers, non-teaching school staff, uniformed services, and employees in cultural institutions. His other pledges are aimed at pensioners, one of the most important groups among ANO’s electorate: they would benefit from ‘fair indexation’ of pensions to ensure a ‘dignified’ level of income and enjoy improved access to social services. Voters over 50 may be attracted by his promise to lower the retirement age to 65 (the current government has approved a mechanism for gradually raising it, partly in response to an ageing population) and to expand the range of professions entitled to early retirement. ANO has also appealed to families with promises of higher child benefits and a state programme to help young families with children repay mortgages.

In fact, housing also plays an important role in the programmes of other parties. The Social Democrats, running on the Stačilo! ticket, have even coined the slogan ‘Housing is our weapon’, using it to criticise what they see as the ruling camp’s excessive focus on modernising the armed forces. SPD intends to expand cooperative housing, make state-owned land available for this purpose, and simplify construction procedures. Passing legislation to ease the strained situation in this sector is one of the key points in the Pirates’ plan for the first 100 days after the elections.

The campaign has featured an unusually large amount of entertainment content, reflecting the spread of new channels and forms of communication with voters. Such content often focuses more on attracting attention than on delivering traditional political messages, although these are also sometimes conveyed in this way. Babiš set the trend after the 2021 elections, when he lost power despite securing the largest number of deputies in the lower house, by overhauling his political marketing team. As a result, ANO activists began flocking to TikTok to build support among younger sections of society, becoming the first politicians from a major party to embrace the platform.

In 2021, only 13 per cent of voters aged 18–34 and 15 per cent of those aged 35–44 cast their ballots for ANO, making it the third choice in both groups, compared with as many as 47 per cent among voters aged 65 and over.[8] By late August 2025, however, the party had become the top choice across all age groups. Among the youngest voters, those under 29, it is now tied with the Spolu (‘Together’) alliance, which forms the core of the current governing coalition.[9]

This trend has also been reflected in the unusual activity of the party’s leading figures. Former (and most likely future) finance minister Alena Schillerová once dressed up as a carton of French fries to draw attention to government measures unfavourable to working students. The party’s chief economic expert, Karel Havlíček, designated by Babiš as ‘prime minister of the shadow cabinet’, has frequently posted videos of his daily routines with his terrier in an effort to improve the image of this otherwise uninspiring politician and to appeal to Czech voters, who view themselves as a ‘nation of dog lovers’. Babiš himself has appeared with a purple Minion mascot intended to symbolise the ‘evil’ Prime Minister Fiala, as the Czech word fialový/-y means both ‘purple’ and ‘relating to Fiala’. He has also posted numerous reports from concerts where he mingled with the crowd, along with short clips suggestively arguing that ‘things were better under Babiš’.

Other parties had long refrained from imitating this strategy, but once its success became evident, they began to emulate it. For example, SPD has recorded a catchy reggae-style song, which now plays at its rallies despite the party’s xenophobic views. Its chairman, in a manner similar to Argentina’s chainsaw-wielding President Javier Milei, appeared with a tool he used to symbolically cut what he considers unnecessary state expenditure – though in this case it was a strimmer. The leader of the Pirates, in a video highlighting housing problems, suddenly appeared in the bed of a young couple. Meanwhile, the chairwoman of the Social Democrats produced a series of ASMR videos in which she repeated the party’s main slogans in a hushed voice. Finally, even Fiala, who had previously cautioned against Chinese threats, opened a TikTok account, although his aides insisted he used a separate phone for this purpose owing to security concerns.

The specifics of Czech elections and key legal aspects

In the Czech version of the parliamentary-cabinet system, securing a majority in the Chamber of Deputies makes it possible to form a government and to pass ordinary legislation (laws that do not require any special procedures), regardless of opposition from the president or the upper house. A statutory majority of the Chamber’s deputies (101 out of 200) is enough to override the Senate’s objections. The same applies to a presidential veto, which clearly distinguishes the Czech system from that of Poland. Therefore, any cohabitation between an ANO-led government and President Petr Pavel, who is generally more aligned with the current centre-right cabinet, should not result in legislative paralysis. However, this does not mean that disputes will not arise in other areas, such as the appointment of the prime minister, ministers, or ambassadors.

At the same time, even an overwhelming majority in the Chamber of Deputies is not enough to amend the constitutional order, a safeguard intended to protect the system from radical transformations. To revise the constitution or adopt one of the so-called constitutional acts – in the past, for example, related to the earlier referendum on EU accession or the regulation of border issues – both houses of parliament must adopt identical provisions with a qualified majority of three-fifths of the statutory number of deputies and senators. Therefore, this process is far more dependent on the composition of the Senate than in Poland, where constitutional amendments require only an absolute majority of votes.

The upper house is currently controlled by the ruling centre-right (60 of 81 seats), and its membership is renewed periodically, with one-third elected every two years (the next elections will be held in a year’s time). This means that extremist parties calling for referendums on leaving the EU or NATO are unable to deliver on these promises. Beyond the opposition from ANO, the largest partner in any potential coalition, the situation in the Senate also works against them, as a qualified majority is required there to pass constitutional acts. The party structure of this chamber is unlikely to change significantly in the near future; the majority electoral system used to select its members also makes it easier to shut out radical candidates. Moreover, the Senate’s opposition cannot be overridden in the case of legislation amending the electoral law.

The rules governing party coalitions have emerged as a contentious issue in the public debate in the run-up to the elections. Formally, such alliances must clear higher thresholds than the basic 5 per cent – 8 per cent for two parties and 11 per cent for three or more. In practice, however, it is common for blocs of parties to run on a joint list without formally declaring a coalition, thus eliminating the need to clear the higher threshold. These thresholds were set in 2021, when the Imperiali formula was introduced into the first stage of converting votes into seats, a change that strongly favoured larger parties.

The governing alliance Spolu represents the only list that must clear the higher national threshold – specifically 11 per cent. It includes Fiala’s right-wing Civic Democratic Party (ODS), the liberal TOP 09 and the Christian Democrats of KDU-ČSL. The alliance was first formed ahead of the 2021 elections and now protects ODS’s smaller partners, which rarely poll above 5 per cent, from losing votes were they to run independently. Spolu is not taking much of a risk, as it is currently polling at about 20 per cent. Nevertheless, this represents a significant drop compared with the more than 27 per cent of votes it secured four years ago.

Controversy surrounding the inclusion of multiple parties on lists qualifying for the basic threshold relates to SPD, whose list also features activists from other far-right parties (Trikolora, PRO, and Svobodní); the communist-led Stačilo!, which includes leading Social Democrats and representatives of smaller groups such as the Moravians; and the Czech Pirate Party, which has offered slots on its list to the Greens. Regional courts reviewing complaints on this issue have often questioned the practice but rejected motions to invalidate the lists, arguing that such a step would amount to excessive judicial interference in the electoral process. They have also cited earlier practice that tolerated so-called hidden coalitions. Consequently, a coalition is treated as such only if it formally classifies itself in this way. However, a shift on this matter may still occur, as the Constitutional Court is scheduled to consider complaints concerning such alliances shortly before or just after the elections.

A separate legal issue that could affect the formation of the post-election government concerns the potential problem of appointing Babiš as prime minister owing to his conflict of interest. He is the owner of the powerful Agrofert holding, which operates in several sectors, including agri-food, chemicals, and forestry. Its companies have received state and EU subsidies and have taken part in public procurement tenders. In the past, this triggered a government crisis that culminated in Babiš’s departure from the cabinet of Bohuslav Sobotka in the spring of 2017 (though ANO remained part of it), while also generating disputes with the European Commission.[10]

Although the Czech Republic has gradually tightened its conflict-of-interest legislation in recent years due to concerns over Babiš’s position and influence, the oligarch has managed to exploit existing loopholes. He temporarily transferred his assets to trust funds over which he effectively retained control through associates who managed them. The government has fully implemented only those provisions that prevent the simultaneous control of media and political activity, but these no longer pose an obstacle for the ANO leader, who has already sold his shares in media companies. However, these outlets remain favourable to him as they are now controlled by a businessman from the chemical sector who has also acquired related assets from Agrofert.

Czech constitutional law experts are divided over whether the president could refuse to appoint Babiš. Most argue that if he becomes the candidate of a parliamentary majority, such a situation should not arise. First, the law provides for a 30-day period from the assumption of office during which any business activities must be terminated. Second, the conflict-of-interest legislation refers only to conducting such activities and holding seats on company bodies, but not to owning shares. However, some lawyers take the view that the president could refuse to appoint him as a way of preventing a potential conflict of interest.

Babiš may also face problems arising from his status as a defendant, and potentially a convict, in the so-called Stork’s Nest case, which has been ongoing since 2015. It concerns the fraudulent acquisition of funds intended for small and medium-sized enterprises to finance the construction of a conference and leisure centre. The latest development came in June 2025, when the Prague Court of Appeal overturned an acquittal delivered by a lower court (the prosecutor general had earlier annulled a similar ruling by that court). In doing so, it imposed its legal interpretation on the municipal court, which must now issue a new ruling, creating a strong likelihood of conviction unless new evidence emerges. However, a decision is expected only a few weeks after the elections. In fact, neither the status of a defendant nor even a conviction formally prevents nomination: former president Miloš Zeman once famously declared that he would appoint the leader of the winning party as prime minister, even if he were serving a prison sentence. For the proceedings to move forward, the lower house would need to vote (for the fourth time) to lift Babiš’s parliamentary immunity. Meanwhile, President Pavel could seize on the ongoing trial and the conflict-of-interest issue to press the ANO leader to nominate another figure from within his party as prime minister.

Outlook

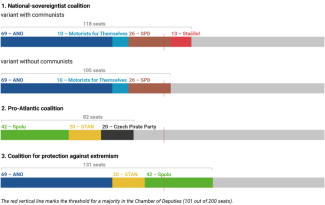

Electoral models based on the latest polls indicate that forming a majority governing coalition without ANO will be virtually impossible (see Chart 2). At the same time, single-party rule under Babiš – something that still seemed plausible a year ago due to divisions and the low polling figures of his rivals – is now difficult to imagine. One reason is that he no longer has an ally in Prague Castle in the form of Zeman, who in the previous term tolerated ANO-led minority governments. More importantly, all recent opinion polls indicate that several parties are set to cross the electoral threshold. These include the left-wing Stačilo! coalition, the increasingly popular Pirates, and even, narrowly, the eurosceptic Motorists for Themselves (5–6%). Meanwhile, SPD has strengthened its position by striking an alliance with other political actors. As a result of all these developments, the 200 seats in the Chamber of Deputies are likely to be divided among a growing number of increasingly competitive electoral lists. In this situation, ANO can expect to secure around 70 seats. Motorists for Themselves, projected to win around 10 seats, should become its most obvious coalition partner.

Among the wider pool of potential coalition partners, the ANO leader is likely to begin talks with the SPD-led far-right alliance, which is projected to win about 25 seats, but the prospects for striking an agreement remain uncertain. SPD activists have already declared their readiness to make far-reaching concessions, including the exclusion of their own leaders from the cabinet, but the radicals are not the preferred partner for Babiš, who has extensive business interests in Western Europe, including Germany, and was recently received by French President Emmanuel Macron.

The former prime minister has previously shared power with the Christian Democrats, now part of the Spolu alliance, and after the last election signalled on several occasions that he would be willing to consider a coalition with ODS, now the largest force within the governing bloc. He has even named figures from the ruling camp with whom he has good relations. Although these politicians have since lost their prominent roles in their parties, they could stir internal opposition after the elections. Liberal media outlets have also discussed such an arrangement as a ‘lesser evil’, particularly in the context of a potential rapprochement between ANO and either the far right or the communists, who are projected to win around 15 seats. Other factors that weigh against ANO’s cooperation with SPD include reports of poor personal relations between Babiš and the SPD leader, Tomio Okamura, as well as doubts about the stability of any majority reliant on radical partners. It seems almost certain that the fragile alliances recently formed between groups competing for a similar electorate – Stačilo! and the SPD list – will sooner or later disintegrate along existing party lines.

An alliance with radical forces – currently the most plausible scenario – would suggest an intention to focus on domestic politics and to adopt a course similar to that pursued by Hungary and Slovakia. It would also enable this camp to implement an ambitious programme of social spending, which the centre-right would seek to block, and to carry out reforms that would in practice dismantle the independence of public media, a move certain to fuel criticism from Brussels. On a personal level, Babiš and Okamura may be united by a desire to halt ongoing criminal proceedings against them. The Chamber of Deputies must vote on each request to lift an MP’s immunity, and it has the power to block such efforts. Okamura might face up to three years in prison in a case related to a controversial billboard campaign which, according to investigators, can be classified as incitement to hatred.

A coalition with part of the governing centre-right would signal a desire to work across party lines in addressing long-term developmental challenges; it would also contribute to greater stability in both domestic and foreign policy. However, such a move would pose a serious credibility problem for the partner concerned, as its narrative has relied heavily on warnings about the potential consequences of Babiš returning to power. From this perspective, the oligarch – whose conflicts of interest and legal troubles have been consistently highlighted by the ruling camp – represents a systemic threat to the effective functioning of a democratic state.

The prospect of reviving the ‘anti-Babiš’ coalition from late 2021 (Spolu, STAN, Pirates) now appears highly unlikely, as the former partners lack sufficient support: together, they can expect to win only 80–90 seats. STAN, a party with roots in local politics and currently polling at 10–12.6%, has an electorate with the highest share of voters open to changing their decision (43%, compared with just 12% for ANO).[11]

The friction between ODS and the Pirates, which contributed to the latter’s withdrawal from the governing coalition, would pose another problem. One factor that may work to these parties’ advantage is the recent incident involving Russian drones over Polish territory, which has lent credibility to the government’s argument about the need to raise defence spending in view of the threat posed by the Kremlin. Prime Minister Fiala stressed that one of the drones had fallen only 200 kilometres from Ostrava; the Czech government subsequently dispatched a helicopter unit to help patrol Poland’s eastern border.

Table. Main political actors and their support

Source: author’s own compilation.

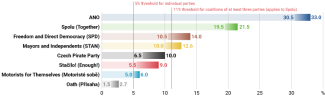

Chart 1. Results of the latest pre-election polls

Source: latest poll results or electoral models from STEM, Median, NMS Market Research, Ipsos, and Kantar.

Chart 2. Potential post-election coalitions

Source: author’s own compilation based on estimated seat allocation from the STEM electoral model (published 14 September).

[1] See K. Dębiec, ‘Fiala’s government halfway through its term: security reinforcement overshadowed by economic problems’, OSW Commentary, no. 574, 16 February 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[2] According to Eurostat data at the end of July 2025, Poland ranked second (27/1000), while France ranked last with fewer than 1/1000.

[3] See K. Dębiec, ‘Czech demography: once a model, now a cause for concern’, OSW Commentary, no. 653, 21 March 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[4] See the Eurobarometer survey published in September 2025. Hungary also recorded 64%, although the share of those strongly convinced of this view was lower at 32%. For Poland, the figures stand at 42% and 17% respectively, while for the EU as a whole – 41% and 18%.

[5] See K. Dębiec, ‘A crisis in the Czech Republic’s relations with China and Russia’, OSW, 2 October 2019, osw.waw.pl.

[6] See A. Sadecki, K. Dębiec, ‘Patriots for Europe: Orbán’s attempt to unite the radical right’, OSW, 23 July 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[7] See K. Dębiec, ‘Czech Republic: the Pirates have fallen overboard from the government’, OSW, 2 October 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[8] E. Černá, T. Vojkovský, ‘Průzkum: mladé ženy nejčastěji volily PirSTAN, 370 tisíc voličů ale uteklo ke koalici Spolu’, iRozhlas, 1 November 2019, irozhlas.cz.

[9] ‘Volební tendence české veřejnosti – SRPEN 2025 – Týdenní model – týden 34’, STEM, 1 September 2025, stem.cz.

[10] See K. Dębiec, J. Groszkowski, ‘Czech Republic: PM Babiš and his conflict of interest comes under European Commission scrutiny’, OSW, 12 June 2019, osw.waw.pl.

[11] Kantar survey, August 2025.