Help from the Far East: Japan’s support for Ukraine

Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine has significantly deepened Ukrainian–Japanese relations, making Tokyo one of Kyiv’s most important partners. This partnership stems from the alignment of both countries’ security interests. Ukraine benefits from Japan’s consistent support, while Tokyo views assistance to Kyiv as an investment in maintaining stability in the Indo-Pacific region. Japan’s interests are threatened by China’s increasingly revisionist ambitions in the region, and successful Russian aggression in Europe could be interpreted by Beijing as encouragement to undertake actions that would undermine Japan’s security. Thus, Japan has taken the initiative in supporting Ukraine, providing aid consistently for over three years, particularly in the form of financial and humanitarian assistance. To date, this support has amounted to $15 billion, with an additional $3.5 billion already announced – placing Japan among the top global donors to Kyiv. While Tokyo still maintains restrictions on the delivery of arms and military equipment, it is actively involved in other key areas, such as non-lethal supplies for Ukraine’s armed forces, infrastructure reconstruction, and demining efforts.

A convergent vision of threats: assessments by Tokyo and Kyiv

The phrase ‘Today Ukraine, tomorrow East Asia?’ – regularly invoked by both former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida,[1] and the incumbent[2] – Shigeru Ishiba[3] – reflects a shared perception of threats in Kyiv and Tokyo. This convergence stems from efforts by Russia in Europe and China in the Indo-Pacific to undermine regional security orders. From Japan’s perspective, the war in Ukraine is more than just a regional conflict. In Tokyo, it is viewed as a litmus test for the global order and for the credibility of the American alliance system, particularly in light of the threats posed to Japan primarily by China.[4]

According to this assessment, a Russian victory could embolden Beijing to escalate tensions around Taiwan and intensify its dispute with Japan over the Senkaku Islands.[5] It would also likely encourage Pyongyang to engage in provocative actions on the Korean Peninsula or directly against Tokyo. In the longer term, it could increase the likelihood of aggressive moves by Russia against Japan – particularly in the context of the unresolved territorial dispute over the Northern Territories (Japanese term), also known as the Southern Kurils (Russian term).

The Japanese have increasingly recognised the growing interdependence between the security of Eastern Europe and East Asia in light of the deepening military ties between Russia, China, and North Korea, as well as the latter two’s involvement in the aggression against Ukraine.[6] The strategic partnership treaty signed in 2024 between Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un has further heightened concerns, particularly over the risk of accelerating North Korea’s nuclear and missile programmes.[7] At the same time, the intensification of military demonstrations by Pyongyang,[8] and Beijing in close proximity to Japanese territory has heightened the sense of threat. Support for Ukraine is therefore a strategic move by Japan, aimed at defending both the global and regional order by weakening Russia, which is viewed as an ally of Japan’s regional adversaries: China and North Korea.

Public sentiment in Japan strongly supports the government’s assistance to Ukraine. In autumn 2024, as many as 74% of Japanese citizens backed aid for the country attacked by Russia.[9] A widespread gesture of solidarity with Ukrainians was the illumination of buildings in yellow and blue. Over the past three years, there has been a significant rise in awareness of, and interest in, Ukraine within Japanese society, which has arguably never before united so strongly in support of another nation.[10] The Russian invasion drew unprecedented attention to this part of the world. According to an IPSOS poll conducted in April 2022, 89% of Japanese respondents were closely following news from Ukraine, and 87% perceived the aggression as a threat to their own national security.[11] Another survey, from March 2022, found that 67% of Japanese people supported sanctions against Russia, even if such measures came at a cost to Japan’s own economy.[12] This attitude has remained largely unchanged: as of August 2025, more than three times as many respondents favoured increasing both aid to Ukraine and sanctions against the aggressor than opposed such measures. However, when it comes to the delivery of arms and military equipment to Kyiv, public resistance continues to outweigh support.[13]

Aligning with public sentiment – and responding to labour market needs – the Japanese government has also revised its previously restrictive asylum policy. Since March 2022, it has accepted 2,747 Ukrainians under a special relocation programme. These individuals were granted complementary protection status, which offers rights and protections comparable to those of refugee status. This represents a significant shift in Japan’s approach, particularly considering that over the past four decades the country had typically approved only about 100 asylum applications annually.[14]

Support for Kyiv is further facilitated by the absence of major issues in bilateral relations. Additionally, Japan is a key partner for Ukraine both in Asia and within the G7 framework.

Table. Declared support to Ukraine as % of GDP (2021) for selected states of the G7 and the Indo-Pacific region (as of August 2025)

Source: ‘Ukraine Support Tracker Data’, Kiel Institute For The World Economy, August 2025, ifw-kiel.de.

Establishing an international coalition and sanctions pressure

Relations with Tokyo have become a significant component of Ukraine’s international support network. Although this cooperation is largely one-sided in terms of immediate, tangible benefits – as Ukraine is currently unable to offer such returns to its partner – it continues to grow, driven by Japan’s proactive approach. A powerful symbol of this commitment was Prime Minister Kishida’s visit to Kyiv in March 2023 – the first by a Japanese leader since the Russian invasion. The timing was particularly significant, as it coincided with the Xi–Putin summit in Moscow, offering a clearly contrasting political message.

Volodymyr Zelensky’s return visit followed just two months later, during the G7 summit in Hiroshima. There, the Ukrainian president had the opportunity to engage in direct dialogue with leaders from Indo-Pacific countries such as the Republic of Korea (South Korea) and Australia, as well as from the Global South, including India, Brazil, member states of ASEAN, and the African Union.[15] Kyiv views its relationship with Tokyo as a valuable channel for reaching countries with which Ukraine maintains only limited ties. This outreach is essential for broadening international support in the fight against the aggressor and for securing favourable outcomes during votes in the UN General Assembly.

Japan has taken measures aimed at reducing Russia’s potential – particularly military and technological – by introducing a range of restrictions. It has joined most Western sanctions targeting the aggressor, including personal and financial measures, as well as restrictions on companies in the military and industrial sectors. Japan has also partially aligned with energy-related (oil) and export restrictions.[16] However, it has avoided participating in EU sanctions on Russian iron and steel and continues to import gas from the Sakhalin-2 project, in which Japanese companies Mitsui and Mitsubishi Corporation remain shareholders.

Tokyo, the second-largest location (after Belgium) where Russian assets are accumulated, has frozen approximately $40 billion worth of Russian property held in Japan. It has also restricted the sale of dual-use goods such as semiconductors and machine tools essential to Russia’s arms production. In addition, as a global leader in electronics manufacturing, Japan has played a key role in hindering Russia’s access to microchips and other components. The restrictions also target entities in third countries that assist Moscow in circumventing the sanctions regime, thereby making a significant contribution to tightening and enforcing the sanctions framework.[17]

Practical support to Ukraine’s defence

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted Japan to ease its long-standing post-World War II restrictions on arms exports. Within the first weeks of the aggression, Tokyo provided Kyiv with support in the form of helmets, bulletproof vests, medical equipment, thermal imaging devices, and chemical weapons protection.[18] This marked the first instance in 80 years of Japan supplying assistance to the armed forces of another country. Another sign of change came in December 2023, when Japan adopted regulations allowing the export of weapons and military equipment manufactured under foreign licences – such as missiles for the Patriot air defence system – to the countries that issued those licences (in this case, the United States). This enabled Japan to support Ukraine indirectly by replenishing US stockpiles, from which deliveries to Kyiv were made.[19] Japan’s only direct financial support for the Ukrainian military came through two contributions – of $30 million and $37 million respectively – to NATO’s Comprehensive Assistance Package (CAP) trust fund, used, among other things, for anti-drone systems.

Japan is supplying Ukraine with specialised vehicles for use in combat zones. In June 2024, it delivered more than one hundred off-road vehicles, including Toyota HMV and Mitsubishi Type 73 models, as well as Morooka PC-065B tracked engineering vehicles.[20] Later that year, in December, Deputy Prime Minister Yuliia Svyrydenko announced plans to assemble Japanese pickup trucks at the Cherkasy Bus Plant. The project is to operate as a joint venture between a Ukrainian manufacturer and a Japanese engineering company, focused on producing the Isuzu D-Max model for military purposes.[21]

The development of security relations was formalised in the bilateral support and cooperation agreement signed on 13 June 2024.[22] The document highlights, among other things, assistance in the field of defence, including support for the needs of the Ukrainian armed forces (excluding weapons). Notably, it is the first security-related agreement that Ukraine has concluded with a non-NATO country.

An important element of the growing cooperation may be the sharing of intelligence by the Japanese company iQPS – something Kyiv began actively pursuing after temporarily losing access to US support of this kind in March 2025. In April, the two sides concluded an agreement on the provision of satellite-based geospatial data and SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) imagery, which can be generated regardless of weather conditions or time of day. The deal with the Japanese demonstrates that, even after the resumption of data transfers from the United States, Ukraine is seeking to reduce its dependence on Washington in this area.[23]

Tokyo has also expressed interest in joining the allied initiative NSATU (NATO Security Assistance and Training for Ukraine), which coordinates military aid and training for Kyiv. In addition, Japan is taking part in discussions at the level of heads of state and chiefs of staff regarding future actions by the so-called Coalition of the Willing, aimed at stabilising the situation in Ukraine in the event of a ceasefire.

A financial lifeline

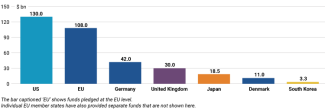

Japan is unequivocally the leading Asian country in supporting the nation under attack, and ranks among Ukraine’s most committed and dependable global partners. In terms of the total value of funds provided and pledged, Japan is surpassed only by the United States, the European Union, Germany, and the United Kingdom. It has allocated approximately $15 billion to this effort and committed to providing a further $3.5 billion (see Appendix for details). The bulk of these funds – approximately $13.25 billion – has taken the form of budgetary assistance, aimed at supporting Ukraine’s financial liquidity and enabling the coverage of civilian expenditure. Over the coming months, Kyiv is expected to receive an additional $2.5 billion. Of the total $15.75 billion, the vast majority – $14.78 billion – has come in the form of loans and credit guarantees. These have been partially financed through frozen Russian assets as part of the G7’s Extraordinary Revenue Acceleration (ERA) initiative.

In addition, Tokyo has provided $1.75 billion and pledged a further $1 billion in humanitarian assistance. This aid includes direct financial support for individuals affected by the war and for Ukrainian refugees abroad. Japan has also participated in initiatives and projects led by other countries or international organisations and has delivered in-kind assistance to those affected by the flooding caused by Russia’s destruction of the dam in Nova Kakhovka.

The scale and nature of Japan’s support for Ukraine are well illustrated by comparing it with that of South Korea – its Asian neighbour – and Denmark – a country allocating a similar overall amount of aid. South Korea has offered Ukraine approximately $3.3 billion, including $2.9 billion in macroeconomic assistance (of which $2.1 billion is a loan for the years 2024–2029) and $400 million in humanitarian aid. Like Tokyo, Seoul has supported Ukraine’s military only with a symbolic amount. Denmark, by contrast, with total assistance amounting to approximately $11 billion dollars,[24] has taken a very different approach – placing the emphasis on military support (approximately $10 billion), with significantly smaller funds allocated to humanitarian aid (approximately $900 million) and financial assistance (approximately $150 million). This contrast clearly highlights the differing character of aid provided by Ukraine’s Asian and European partners.

Chart. The value of support for Ukraine provided and pledged by selected countries and institutions (as of August 2025)

Source: ‘Ukraine Support Tracker Data’, Kiel Institute For The World Economy, August 2025, ifw-kiel.de.

Seeking investment and reconstruction with Japan’s involvement

Increasing Japanese investment and Tokyo’s involvement in Ukraine’s reconstruction are key priorities for Kyiv. In 2024, two major events helped to intensify economic relations between the two countries: the Japan–Ukraine Conference for the Promotion of Economic Growth and Reconstruction in Tokyo (19–20 February) and the Ukraine–Japan Business Forum in Osaka (18 December). The Tokyo conference brought together approximately 200 companies, which signed 56 agreements on infrastructure reconstruction, demining, agriculture, biotechnology, industry, information technology, humanitarian issues, and the improvement of public administration.[25]

Leading representatives of the Ukrainian government are encouraging Japanese entities to invest in areas such as lithium exploitation for electric vehicle production and the reconstruction of industrial facilities.[26] Kyiv hopes to attract Japanese manufacturers to establish production in Ukraine and to set up joint ventures.[27] Tokyo supports these investment efforts through dedicated agencies such as the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) and Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (NEXI). In 2023, JETRO opened an office in Kyiv and has been organising business trips to assess local potential for joint projects. NEXI’s task, on the other hand, is to encourage companies to enter the Ukrainian market – it has allocated €1.25 billion for guarantees and credit lines.[28] Currently, more than 40 Japanese companies operate in Ukraine, primarily in the automotive, energy, and technology sectors.

The development of bilateral economic cooperation faces significant obstacles. The limited presence of the Japanese private sector in Ukraine is largely due to widespread corruption in the country,[29] as well as concerns over the safety of business ventures and personnel. These challenges are further compounded by a Level 4 travel advisory issued by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in February 2022, warning against visits to Ukraine. This advisory makes it difficult to dispatch employees or engage in projects, particularly given that such government recommendations are widely adhered to in Japan. Companies such as Toyota and Mitsubishi Motors are exercising caution also due to pressure from Russia, which seeks to deter businesses that previously operated in the Russian market – and may consider returning in the future – from investing in Ukraine. Moscow has threatened the permanent severance of trade ties with companies that pursue such investments. In response, Kyiv is focusing on attracting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which tend to be more willing to take on risk. It is also considering opening trade representative offices in Osaka and Kyoto to facilitate business contacts and overcome logistical and informational barriers.

An essential condition for the effective reconstruction of Ukraine is the efficient demining of its territory.[30] Japan, recognised as a leader in this field, developed its expertise through its long-standing assistance to Cambodia following more than two decades of conflict there. Tokyo and Phnom Penh have now jointly developed demining expertise, which they are transferring to Ukraine. This includes the delivery of mine clearance machinery and the training of Ukrainian sappers in how to operate it.[31] Ukraine is using mechanised demining vehicles produced by Komatsu and Nikken, delivered through the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) – one of the largest development aid agencies in the world. JICA has already supplied several hundred units of specialised equipment and gear, significantly improving both the safety and efficiency of the demining process in Ukraine.[32] In addition, the Ukraine Mine Action Conference (UMAC 2025) is scheduled to take place in Tokyo in autumn 2025. The event will bring together Ukraine’s key international partners to coordinate their efforts in the field of demining.[33] Japanese experts also regard this assistance as a testing ground for their own developing technologies, including artificial intelligence.[34]

JICA is also carrying out numerous energy, infrastructure, and humanitarian projects in Ukraine, aiming to offset the effects of reduced funding from USAID. To date, it has allocated approximately $1.5 billion in the form of financial resources, equipment, and technology. This includes $58 million for the reconstruction of infrastructure, water supply systems, and waste management. Tokyo supports municipal services in regions most affected by the war by providing, among other things, protective gabions (stone-filled structures) to safeguard critical infrastructure, as well as vehicles, generators, power transformers, and medical equipment. It also assists in debris removal and processing. Japanese companies such as Sumitomo Corporation and Komaihaltec, in cooperation with Naftogaz, are implementing energy infrastructure modernisation projects. In January 2025, a joint platform was launched: JUPITeR (Japan–Ukraine Platform on the Infrastructure Technology for Recovery and Reconstruction), which promotes reconstruction efforts through Japanese technologies and investment.[35]

Challenges to the partnership

Ukraine intends to deepen its cooperation with Japan, hoping for continued financial and humanitarian support as well as increased investment in key sectors of the economy: automotive, energy, and technology. To that end, it will propose joint initiatives such as the production of electric vehicles using Ukrainian lithium and the expansion of 5G infrastructure. Kyiv also views Tokyo as a gateway to reaching Southeast Asian and Global South countries, with the aim of securing their diplomatic support in building an international coalition against Russia. In addition, Ukraine expects continued assistance in demining operations and the provision of intelligence data to increase its stability and enhance its appeal to investors.

Despite the dynamic development of their relations, Japan and Ukraine also face shared challenges. The primary one will be mitigating potential negative consequences of US policy – particularly as the United States remains Japan’s key ally and its engagement in Ukraine’s peace process is essential for ending the war in Europe. The Trump administration is shifting away from the paradigm of integrated theatres of operation and prefers that NATO allies in the Indo-Pacific – the so-called AP4 – focus on their own region, rather than on the European continent. Nonetheless, Japanese support for Kyiv is expected to continue, along with further enhancement of bilateral cooperation – and possibly its gradual expansion into new areas such as cybersecurity.

APPENDIX. Japan’s support for Ukraine

Macroeconomic assistance (approximately $15.75 billion):

- $600 million in the form of a loan granted via the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development,

- $5.5 billion in the form of credit guarantees and grants offered via trust funds such as ADVANCE and the World Bank’s URTF,

- $4.5 billion in the form of credit guarantees offered under World Bank programmes,

- $470 million in the form of a grant offered via the World Bank’s PEACE MDTF trust fund,

- ¥471.9 billion (approx. $3.3 billion) in the form of a loan under the ERA initiative.

Humanitarian assistance (approximately $2.75 billion):

- $500 million for international organisations operating in Ukraine, and also in the form of humanitarian aid and support for recovery and reconstruction,

- $400 million via the JICA agency for demining and debris removal equipment, reconstruction of infrastructure, agriculture recovery, as well as democratisation and enhanced governance,

- $1 billion for humanitarian assistance and support for recovery and reconstruction,

- $162 million via the JICA agency for the modernisation of transport services, water supply, and waste recycling systems,

- $110 million via the JICA agency for demining, energy, transport, and the development of public-private partnerships,

- $95 million under the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for demining, support for victims, waste management, crisis management, and reconstruction planning.

Support for the Ukrainian army ($67 million):

- $30 million contributed to the NATO CAP trust fund (Comprehensive Assistance Package for Ukraine) for non-lethal equipment,

- $37 million contributed to NATO CAP, including for anti-drone systems.

[1] ‘Written Interview with Prime Minister KISHIDA Fumio by the Lithuanian Radio and Television (LRT)’, Office of the Prime Minister of Japan, 12 July 2023, japan.kantei.go.jp.

[2] On 7 September, Shigeru Ishiba announced his resignation as Prime Minister and President of the Liberal Democratic Party. He will remain in office until the new leader of the ruling party is elected.

[3] ‘DSEI Japan 2025: “Today’s Ukraine could be East Asia tomorrow”, Japan’s PM says’, DSEI Japan, 22 May 2025, dsei-japan.com.

[4] Munich Security Index 2025, Munich Security Conference, February 2025, securityconference.org.

[5] K. Weber, ‘Morskie spory w rejonie Azji Wschodniej. Rywalizacja o wyspy Senkaku oraz Dokdo’ [in:] R. Kordonski, Ł. Muszyński, O. Kordonska, D. Kamilewicz-Rucińska (eds), Transformacja środowiska międzynarodowego i jego wielowymiarowość, vol. 3, Lwów–Olsztyn 2017 (p. 111–120), after: intrel.lnu.edu.ua.

[6] S. Kwon, ‘Emerging Threats and U.S.-ROK-Japan Security Cooperation in Northeast Asia’, The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR), 23 January 2025, nbr.org.

[7] W. Rodkiewicz, ‘Russia signs a military alliance with North Korea’, OSW, 20 June 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[8] J. Johnson, ‘North Korea fires off 'multiple' ballistic missiles in latest show of force’, The Japan Times, 18 September 2024, japantimes.co.jp.

[9] D. Bricker, World affairs. Citizens of 30 Countries Assess Threats and Engagement in International Affairs, Ipsos World Affairs, November 2024, ipsos.com.

[10] According to Ukraine’s former ambassador to Japan Sergiy Korsunsky, ‘Японія та Україна: дипломатичний погляд зсередини’, Hypercube, 21 May 2025, youtube.com.

[11] C. Jackson, ‘61% globally think the war in Ukraine poses a significant risk to their country’, Ipsos, 19 April 2022, ipsos.com.

[12] ‘Survey: 67% of Japanese favor sanctions against Russia’, The Asahi Shimbun, 22 March 2022, asahi.com.

[13] T. Goroku et al., ‘UTokyo ROLES Survey’, University of Tokyo, 4 September 2025, roles.rcast.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

[14] M.X. Rehm, ‘Still a Negative Case? Japan’s Changing Refugee Policy in the Face of New Geopolitical Challenges’, Asia-Pacific Journal, Japan Focus, 19 June 2024, apjjf.org.

[15] J. Irish, S. Murakami, ‘Ukraine's Zelenskiy courts 'Global South' at G7 summit’, Reuters, 21 May 2023, reuters.com.

[16] ‘Russia Sanctions Tracker – Japan’, Ashurst, 17 January 2025, ashurst.com.

[17] ‘Japan Expands Russia Sanctions With Fresh Asset Freezes, Export Bans’, The Moscow Times, 10 January 2025, themoscowtimes.com.

[18] ‘Signing and Exchange of Notes for the Grant of JSDF Equipment and Goods to Ukraine’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 8 March 2022, mofa.go.jp.

[19] N. Tajima, ‘In major shift, Japan gives nod to exports of lethal weapons’, The Asahi Shimbun, 23 December 2023, asahi.com.

[20] ‘Японія надала Україні понад сотню спецавтомобілів’, Укрінформ, 6 June 2024, ukrinform.ua.

[21] ‘Japan to launch pickup truck production in Ukraine to meet military demands for reliable off-road vehicles’, Army Recognition, 18 December 2024, armyrecognition.com.

[22] ‘Угода про підтримку України та співробітництво між Україною та урядом Японії’, President of Ukraine, 13 June 2024, president.gov.ua.

[23] M. Mitkow, ‘Japonia zapewni Ukrainie dane satelitarne SAR’, Space24, 25 April 2025, space24.pl.

[24] K. Nieczypor, P. Szymański, J. Tarociński, ‘A trusted ally? Denmark’s involvement in helping Ukraine’, OSW Commentary, no. 681, 25 July 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[25] ‘Japan-Ukraine Conference for Promotion of Economic Growth and Reconstruction’, Office of the Prime Minister of Japan, 19 February 2024, japan.kantei.go.jp.

[26] S. Seno, ‘Ukraine prime minister seeks Japanese investment in EVs and beyond’, Nikkei Asia, 17 February 2024, asia.nikkei.com.

[27] ‘Торгівля із Японією зросла на 6% у 2024 році і ще на 30% торік, — Юлія Свириденко під час бізнес-форуму в Осаці’, Government of Ukraine, 18 December 2024, kmu.gov.ua.

[28] Y. Nakano, ‘Japan’s Leadership Role on Ukraine’, Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 22 February 2024, csis.org.

[29] At the same time, Tokyo views its support for Kyiv’s anti-corruption efforts as a means to achieving Ukraine’s institutional stability and increasing its investment appeal. It is also involved in initiatives such as the Anti-Corruption Task Force for Ukraine.

[30] K. Nieczypor, ‘Ukraine: the world’s biggest minefield’, OSW Commentary, no. 556, 22 November 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[31] ‘Японія і Камбоджа спільно допоможуть розмінувати Україну’, LRT, 8 July 2024, lrt.lt.

[32] ‘У ДСНС відбулася робоча зустріч з представниками Японського агентства міжнародного співробітництва JICA’, State Emergency Service of Ukraine, 21 May 2025, dsns.gov.ua.

[33] ‘Masashi Nakagome: Japan will continue to stand firmly with Ukraine in its time of need’, New Europe Centre, 7 March 2025, neweurope.org.ua.

[34] J. Ryall, ‘How Japan uses heavy machinery and AI to clear Ukraine mines’, Deutsche Welle, 13 May 2025, dw.com.

[35] ‘Україна та Японія налагоджують співпрацю для залучення приватного сектору у відбудову’, Ministry for Communities, Territories and Infrastructure Development of Ukraine, 6 March 2025, mindev.gov.ua.