A trusted ally? Denmark’s involvement in helping Ukraine

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Denmark has allocated €8.5 billion for military aid and €854 million for civilian support to Kyiv. According to data compiled by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, this sum – alongside the funds planned to be disbursed by 2028 – positions Denmark sixth globally in terms of total aid provided (after the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Japan), and second in relation to GDP (2.34%), following only Estonia. This scale of support is particularly notable given that Denmark ranks sixteenth in Europe and thirty-fourth globally in terms of GDP.

An example of an innovative approach to military support is the so-called Danish model, which involves financing the production of weapons in Ukraine – an initiative that has already been adopted by Sweden, Lithuania, and the European Union. Copenhagen’s consistency in this regard is reflected in its comprehensive involvement in reconstruction projects in Mykolaiv Oblast, and above all, its capital. Copenhagen regards the implementation of the Danish model of military support, and Denmark’s significant role in the reconstruction of Mykolaiv, as investments in its own security – by weakening Russia and thereby counteracting its attempts to expand influence in the Baltic Sea region.

Aid ‘with no qualms’

Danish support for Ukraine forms part of Copenhagen’s consistent stance toward Moscow’s aggressive actions following the annexation of Crimea. As early as 2015, Danish soldiers joined the Canadian (UNIFIER) and British (Orbital) training missions in Ukraine. In January 2022, during a visit to the so-called contact line in the Donbas, the Danish foreign minister announced the provision of €22 million in financial assistance in response to the build-up of Russian troops along Ukraine’s border. A month later, Defence Minister Morten Bødskov declared that ‘Denmark has no qualms about helping to arm Ukraine’. After the invasion began, Copenhagen decided to send 2,700 anti-tank weapons and 300 Stinger missiles to Ukraine. According to Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen, this marked the first instance in modern Danish history of delivering military equipment to a side actively engaged in conflict. In spring 2022, Copenhagen also donated coastal missile batteries armed with Harpoon anti-ship missiles to Kyiv, which are reported to have played a key role in defending Ukraine’s Black Sea coastline – including Odesa – and contributed to the recapture of Snake Island.

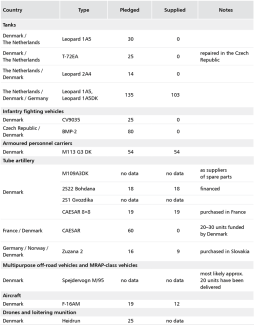

In cooperation with Germany, Denmark delivered over 100 Leopard 1A5 tanks, and together with the Netherlands, committed to purchasing and transporting 14 Leopard 2A4 and 15 T-72 tanks to Ukraine. In August 2024, again in partnership with the Netherlands, Denmark handed over the first F-16 fighter jets to Kyiv. Earlier that year, in February, it also transferred 19 French CAESAR self-propelled howitzers from its own military stockpiles, thereby relinquishing all of Denmark’s self-propelled artillery systems (see Table). The military aid Denmark provided to Ukraine in 2023 – amounting to approximately €1.7 billion – represented more than a quarter of Denmark’s annual defence budget at the time, which was approximately €6.3 billion.[1]

Moreover, Denmark was the first country outside the G7 to sign a bilateral security cooperation agreement with Ukraine, with similar agreements having been concluded by 28 countries. Copenhagen is actively engaged in seven out of nine coalitions under the Ukraine Defence Contact Group (the so-called Ramstein Group) and leads one of them – responsible for coordinating support to the Ukrainian air force. Since 2022, more than 100 Danish instructors have taken part in training Ukrainian soldiers as part of the British-led Operation Interflex, especially in preparing air force personnel, artillery units, sappers, and tank crews. Furthermore, the Danish Prime Minister – who has visited Ukraine six times since the outbreak of the war – was the first European leader to declare that Danish citizens may, without legal impediment, join the Ukrainian armed forces to fight the aggressor.

Support across the party lines

The resolute actions of the Danish government are made possible by a broad social and political consensus on the necessity of supporting Kyiv. Russian aggression is perceived not only as a threat to the international legal order, but also as a direct danger to the interests of the Kingdom of Denmark.[2] Copenhagen regards support for Ukraine in its fight as the best security policy, as it weakens Russia and curbs its ambitions to re-establish a sphere of influence, particularly in the Baltic Sea region. Denmark fears that, after the war ends, Russia will seek to rebuild its military capabilities and undertake armed actions against countries situated around this body of water.

This conviction led the majority of political parties in Denmark to forge a cross-party agreement on defence in April 2024, enablingthe country to reach the 2% of GDP threshold for defence spending within the same year (initially planned for 2030). Furthermore, in February 2025, Denmark declared its intention to raise this figure to 3.2% over the next two years. This sharp increase in defence expenditure was also driven by pressure from Donald Trump – first as a presidential candidate and later as President of the United States – on European countries to boost their military spending, and by US demands concerning Greenland, an autonomous territory under Danish sovereignty.

The roots of the stance adopted by Danish society and political class on Ukraine and the Russian invasion lie in a deeply ingrained imperative of international activism within Denmark’s foreign and security policy, which took shape after the Cold War. Copenhagen strongly supported NATO and EU eastward enlargement – particularly the aspirations of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia – and, as a small state, consistently backed a rules-based international order. As a result of geopolitical changes, Denmark ceased to see itself as a frontline state and, until 2022, did not perceive a direct threat of military aggression. This outlook underpinned Denmark’s readiness to engage militarily abroad and participate in various ‘coalitions of the willing’.

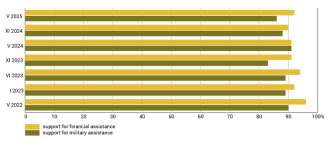

Chart. Danish public’s support for helping Ukraine

Source: Eurobarometer.

The Danish model of military assistance: achievements…

Gradual depletion of Denmark’s own military equipment stockpiles, together with the limited production capacity of the European defence industry, compelled the Danish authorities to seek creative solutions to support Ukraine’s war effort. In June 2024, Kyiv and Copenhagen signed an agreement to finance the production of 18 2S22 Bohdana wheeled self-propelled howitzers. This was the first pilot arrangement in which a NATO country reimbursed Ukraine for a defence order fulfilled by the Ukrainian arms industry.[3] The howitzers were delivered to the front in a relatively short period, which led to a continuation of the partnership and an expansion of production with the involvement of additional partners. Thanks to the implemented external financing mechanism, the production capacity for Bohdana howitzers was projected to increase from a few units to 20 per month in 2025.

The proposed cooperation model also proved successful because it significantly reduced the cost of weapons production compared with purchasing them in Europe. A single Bohdana self-propelled howitzer costs approximately $2.5 million, while the comparable French CAESAR system costs around $4.2 million. Locating part of the production in Ukraine also enabled faster delivery of spare parts, resulting in more efficient servicing of the weapon systems and thereby extending their operational lifespan. In September 2024, representatives of Ukraine’s ministries overseeing strategic sectors of the economy and the Danish Ministry of Defence signed an agreement to expand cooperation to include other categories of weapons and military equipment: long-range drones, anti-tank systems, and anti-ship missile systems. Sweden and Iceland also joined the initiative.

Evidence of the Danish programme’s success in financing the production of Bohdana self-propelled howitzers was the European Union’s decision to invest further funds in the Ukrainian defence industry: €390 million in September 2024 (part of which was allocated to finance the production of another batch of howitzers), followed by €830 million in May 2025, sourced from interest accrued on frozen Russian assets under the ERA (Extraordinary Revenue Acceleration) initiative. Denmark was designated as the operator responsible for executing the procurement in cooperation with Kyiv. The funds are to be allocated primarily to the production of drones and ammunition.

According to President Volodymyr Zelensky’s , thanks to the ‘Danish model’, Ukraine managed to increase its production to a level corresponding to more than 40% of all weapons and military equipment used on the front line (at the start of the war, this figure was less than 10%).[4] According to the then Minister for Strategic Industries, Herman Smetanin, domestic arms production in 2024 tripled compared with the previous year (from $3 billion to $9 billion), and the defence industry gained the capacity to fulfil orders worth $20 billion, with the prospect of reaching $35 billion in 2025.[5] More than 800 arms companies are involved in the initiative in Ukraine, employing around 300,000 individuals – nearly half the workforce of the entire European defence industry.[6]

…and limitations

An obstacle to fully utilising Ukraine’s defence industry is the reluctance of international partners to finance it directly, bypassing their own domestic industries. Berlin prefers to establish joint German-Ukrainian ventures, which are expected to result in the construction of a munitions factory in Ukraine, along with production and maintenance facilities for tanks, artillery systems, and air defence equipment.[7] France likewise favours a similar model.[8] Consequently, despite widespread declarations of interest in the ‘Danish model’, the total value of foreign orders placed with Ukrainian defence companies remains relatively low. According to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, from the start of the war until December 2024, these orders amounted to €1 billion. Given that the total value of military equipment procured for Ukraine by its allies last year reached approximately €54 billion, this represents only 2% of all international arms purchases made on behalf of the Ukrainian armed forces.[9]

To increase investment in Ukraine’s defence industry, Denmark announced in October 2024 the establishment of the Defence Industry Hub. The goal of this initiative is to promote collaboration between Danish companies and their Ukrainian counterparts in jointly executing military procurement projects. An additional incentive came with the launch, in March 2025, of a programme offering guarantees worth 1 billion Danish kroner (over €130 million) to Danish enterprises willing to invest in Ukraine’s defence sector. Under this programme, the Export and Investment Fund of Denmark (EIFO) offers to cover up to 70% of capital expenditures for a period of up to seven years.

Reconstruction: a ‘Copenhagen’ on the Black Sea

Although military assistance accounts for approximately 80% of Denmark’s financial and material support to Ukraine, Copenhagen has also committed substantial funds to civilian purposes. Since 2022, it has donated €867 million for non-military aid, the flagship initiative in this area being support for the reconstruction of Mykolaiv. The choice of this city was prompted by a direct appeal from President Volodymyr Zelensky, coinciding with a Russian missile strike on the regional administration building that killed 37 people.[10] Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen announced the aid programme for the city in April 2022 during her visit to Ukraine. In the same month, a Danish-Ukrainian task force began developing the project’s framework, which was published in June 2022. Subsequently, in March 2023, a memorandum on the partnership between Denmark and Mykolaiv was signed, and a Steering Committee was established. This body includes relevant ministries and institutions from both Denmark and Ukraine, as well as representatives of local authorities. In October 2023, the Embassy of the Kingdom of Denmark opened its local office in Mykolaiv.

In practical terms, during the first months following the successful defence of Mykolaiv against Russian forces, Danish assistance focused almost exclusively on emergency repairs to the city’s water and electricity infrastructure. The primary goal was to halt the exodus of residents, particularly young people, caused by harsh living conditions. By the end of 2022, more than 220,000 people – nearly half of the city’s pre-war population – had left.

By November 2022, due to the ongoing occupation of Kherson – where the pipeline supplying Mykolaiv with drinking water from the Dnipro River originated – the city was entirely cut off from potable water. The situation was exacerbated by the deliberate destruction of that infrastructure by Russian forces, followed by the demolition of the dam in Nova Kakhovka. This forced city authorities to resort to using contaminated seawater, which caused critical damage to the water supply network and necessitated the replacement of approximately 1,200 kilometres of municipal piping. With the support of Denmark and other partners, water purification equipment was delivered, and since January 2025 construction has been under way on a new 67-kilometer pipeline from Nova Odesa to Mykolaiv. As part of this investment project (valued at approximately €132 million), Denmark committed to replacing approximately 45 kilometres of the most severely damaged parts of the municipal water system and to fully rebuilding it in one of the city’s most densely populated and industrialised districts. The project is scheduled for completion by the end of 2025.

Another challenge is the electricity shortfall caused by damage to combined heat and power plants and the transmission grid. Denmark has pledged to co-finance a new wind power plant, one of the largest reconstruction projects planned in Ukraine (with an estimated cost of approximately €400 million).[11] The investment is expected to be operational by the end of 2026. In parallel with this initiative, Denmark commissioned the Kyiv School of Economics to prepare a report on the scale of destruction based on satellite and drone imagery. In the report published in December 2022, war-related losses were estimated at €852 million.[12] These data were used by Danish and Italian design studios to develop a reconstruction strategy for Mykolaiv (commissioned by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs), the principal assumptions of which were incorporated into the official Mykolaiv Recovery and Development Plan for 2024–2027.[13] This year, conceptual work has begun on the implementation of two key projects included in the plan: the construction of an industrial park and the revitalisation and reconstruction of the shipyard facilities.

According to the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as of 25 February 2025, Copenhagen has allocated approximately €190 million in aid for Mykolaiv. This amount constitutes 60% of all funds earmarked thus far for Ukraine’s reconstruction, in line with the objectives of the Danish Fund for Ukraine launched in March 2023. Denmark is also striving to encourage private entities to participate in the reconstruction not only of Mykolaiv but also of other parts of the country. To support this objective, a special Instrument for Ukraine was launched in March 2023. Operated via EIFO, it offers loans and credit guarantees of up to 1 billion Danish kroner (over €130 million). The instrument enables financing and full guarantees (up to 100%) of the cost of goods from Danish exports purchased by Ukrainian entrepreneurs. It also provides grants to Ukrainian public institutions covering up to 40% of the cost of purchasing goods for projects related to critical infrastructure. In addition, EIFO offers loans and guarantees to Danish companies operating in Ukraine and creating new jobs there.

Due to deliberate shelling of investment sites, information regarding the location and scale of foreign-funded reconstruction projects is not disclosed to the public. This decision followed a Russian missile strike in August 2023 on facilities belonging to the Mykolaiv-based agroholding Nibulon – one of the largest companies in Ukraine – the reconstruction of which was financed under EIFO. Danish authorities currently report more than 20 completed projects in Mykolaiv, marking the next stage in the implementation of the city’s development concept aimed at encouraging resettlement. In this context, alongside industrial development and job creation initiatives, particular attention is given to social investments, such as the reconstruction of educational facilities, including the historic Mykola Arkas Lyceum.

As emphasised by the city’s mayor, Oleksandr Sienkevych, the concept of cooperation with the Danes envisages an urban development model for Mykolaiv inspired by Copenhagen,[14] which carries both practical and measurable implications. The Danes makeno secret of the fact that their involvement in the reconstruction is, from their perspective, associated with anticipated economic benefits resulting from closer shipbuilding cooperation between Denmark and Ukraine after the war. The investments in renovating the water supply network in the so-called shipbuilding district (home to numerous shipbuilding enterprises and Olvia, one of the country’s most modern seaports) along with plans to restore professional expertise through the rebuilding of Admiral Makarov National University of Shipbuilding in Mykolaiv, form part of a coherent vision pursued by Danish decision-makers.[15] This approach is reflected in the Memorandum of Understanding on Long-Term Cooperation and Reconstruction of Ukraine, signed between the two countries in April 2024, in which a significant portion is devoted to joint projects aimed at developing the shipbuilding industry.[16]

Denmark as a model

Compared with other Western countries providing aid to Ukraine, Danish support is significantly smaller than that offered by wealthier partners such as the United States, the United Kingdom, or Germany, and does not exert a decisive impact on strengthening Ukraine’s war effort. At the same time, it is characterised by a consistent and comprehensive approach, which sets Denmark apart from other states supporting Kyiv. This is evidenced by the launch of the so-called Danish model of military assistance and Copenhagen’s participation in the reconstruction of Mykolaiv. Consequently, Denmark’s involvement is both visible and appreciated by Ukrainian decision-makers and society alike (70% of respondents indicated a positive attitude toward Denmark).[17]

President Zelensky has presented the Danish stance as a model to follow. In recognition of this support, he wrote on X that had all of Ukraine’s allies been as resolute as Copenhagen, the Russian aggressor would have been stopped long ago.[18]

Table. Military equipment supplied by Denmark to Ukraine

Source: ‘OSW’s Arms deliveries monitor’, osw.waw.pl.

[1] The disproportionate increase in military spending compared to the allocated financial resources led to a budget deficit of approximately €50 million in Denmark’s defence budget in 2024. Consequently, the Danish armed forces were forced to cancel their participation in NATO exercises and training initiatives, grant some military personnela two-week leave, and implement cost-saving measures such as limiting the use of office equipment. E. Ahmed, ‘Danish army struggling to finance basic expenses due to austerity measures’, Anadolu Agency, 17 July 2024, aa.com.tr/en.

[2] The government report Danish Security and Defence towards 2035 published in September 2022 argued that Denmark must be prepared to ‘provide similar support to countries such as Georgia or Moldova should Russia choose to attack them’. Similar conclusions were presented in a report published in January 2025 by the Danish Defence Intelligence Service, which warned that after the conflict in Ukraine ends, Russia may rebuild its armed forces and within the next two to five years undertake military action in the Baltic Sea region. Intelligence Outlook 2024, Danish Defence Intelligence Service, December 2024, fe-ddis.dk.

[3] The production of these vehicles was most likely based on cooperation with the Slovak ZVS Holding company, which was in place before the full-scale war. ‘Словацький ZVS Holding готовий допомогти Україні з прискоренням розробки САУ "Богдана" та самохідного самозарядного міномету’, Defense Express, 23 November 2020, defence-ua.com.

[4] K. Hodunova, ‘Over 40% of Ukrainian forces’ weapons domestically produced, Zelensky says’, The Kyiv Independent, 16 April 2025, kyivindependent.com.

[5] І. Носальський, ‘Україна у 2024 році виробила зброї на 9 млрд доларів: прорив у ракетах і не тільки’, РБК-Україна, 11 April 2025, rbc.ua.

[6] ‘ZBROYARI: Manufacturing Freedom’, zbroyari.gov.ua.

[7] I. Kabachynskyi, ‘How German Defense Giant Rheinmetall Powers Up Ukraine’s Defense’, United24 Media, 29 October 2024, united24media.com.

[8] ‘French defence companies to build military equipment on Ukrainian soil – minister’, Reuters, 8 March 2024, reuters.com.

[9] P. Bomprezzi et al., ‘Ukraine Support After Three Years of War: Aid remains low but steady and there is a shift toward weapons procurement’, Kiel Institute for World Economy, 14 February 2025, ifw-kiel.de.

[10] Apart from the coincidental timing of President Zelensky's address and the tragic event that occurred earlier the same day, the decision was also justified by the existing cooperation between Mykolaiv and Denmark. In December 2021, Denmark and Ukraine signed a memorandum on cooperation in the maritime sector, which included provisions for the construction of Danish vessels in Ukrainian ports. ‘Україна і Данія спільно будуватимуть кораблі – підписаний меморандум’, Укрінформ, 18 December 2021, ukrinform.ua. Several months earlier, both sides had discussed the possibility of launching the construction of patrol vessels in Mykolaiv, after the Danish side ended its cooperation with the Gdańsk Shipyard. Р. Рудомський, ‘Знову патрульні кораблі: Що за Knud Rasmussen Україна хоче виготовляти разом з Данією’, Depo.ua, 19 May 2021.

[11] А. Гакман, ‘«Найбільша приватна інвестиція»: Данія виділить €400 млн на будівництво Тилігульської вітроелектростанції, що на Миколаївщині’, МикВісті, 4 February 2025, nikvesti.com.

[12] A. Ткаченко, ‘"Найбільше постраждав житловий фонд": Миколаїв через рашиську агресію зазнав збитків на 852 млн євро’, 0512 – Сайт міста Миколаєва, 17 December 2022, 0512.com.ua.

[13] ‘Mykolaiv Concept Masterplan was presented to municipality’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, 4 July 2024, ukraine.um.dk.

[14] U. Poletti, ‘Mykolaiv, the Danish Model for Rebuilding Ukraine – Without Corruption’, Kyiv Post, 24 March 2024, kyivpost.com.

[15] According to the Danish ambassador in Kyiv (formerly stationed in Warsaw), the goal of Danish assistance is to rebuild Mykolaiv’s shipbuilding capacity, which would allow it to compete, among others, with Poland. О. Колесніченко, ‘Посол Данії в Україні: Миколаївські суднобудівні заводи можуть конкурувати з верфями Польщі, Кореї, Китаю’, Економічна правда, 21 November 2023, epravda.com.ua.

[16] ‘Ukraine and Denmark sign the Memorandum of Understanding on long-term cooperation and reconstruction of our country’, Ministry of the Economy of Ukraine, 26 April 2024, me.gov.ua.

[17] Ставлення українців до країн світу. Результати дослідження громадської думки, квітень 2025 року, SunFlower Sociology, April 2025, expertsclub.eu.

[18] See a tweet by Volodymyr Zelensky, 7 December 2024, x.com/ZelenskyyUa.