A nationalist voice of protest: the resurgence of radical parties in Bulgaria

The political crisis that has persisted in Bulgaria since 2021 initially weakened traditional nationalist forces, which lost their parliamentary representation. However, the transitional period was seized upon by new radical parties, including Revival, which gained the most popularity. Their platform combines nationalist-sovereigntist rhetoric with anti-corruption demands. In addition to nationalist voters, these groups also managed to attract a segment of the anti-establishment and reformist electorate, disillusioned by previous efforts to reform state institutions. According to opinion polls, the three radical parties currently represented in parliament enjoy combined support of around 20–25% of the population, yet they lack realistic prospects of taking power. Nevertheless, they arecapable of shaping public sentiment and negatively affecting the country’s international image. They challenge Sofia’s main foreign policy directions, oppose aid to Ukraine and openly call for a return to closer ties with Russia. It cannot be ruled out that the popularity of these radical parties will continue to grow in the coming months, particularly in view of Bulgaria’s plans to adopt the euro on 1 January 2026.

Profiles of radical parties: pro-Russian revisionists…

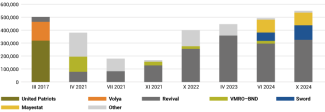

The most popular, and at the same time the most extreme, radical party in Bulgaria is Revival (Възраждане). It first entered parliament in 2021 – seven years after its founding. Since then, it has steadily strengthened its position on the political scene (see chart). Its best electoral result came in 2023, when it won nearly 360,000 votes (14.2%). It currently holds 33 seats in the 240-member National Assembly, making it the third-largest party. Revival’s MPs often employ sharp nationalist rhetoric, calling for sweeping changes to Sofia’s domestic and foreign policy.

At the heart of the party’s platform lies its titular concept of ‘revival,’ understood as a spiritual, cultural, and institutional renaissance of Bulgaria. This includes restoring the agency of the state, reforming the judiciary, increasing spending on culture and education, and supporting the sustainable development of all regions. The party draws on Orthodox Christian values, opposing what it claims is the indoctrination of children and young people by left-wing movements and progressive NGOs. In 2024, at Revival’s initiative, parliament passed a law banning the promotion of ‘non-traditional sexual orientations’ in schools, inspired by similar legislation in Russia and Hungary.

Revival’s economic proposals are a blend of sovereigntist, statist, and free-market views. The party is the main voice of protest against Bulgaria’s adoption of the euro.[1] It regularly organises demonstrations in defence of the local currency, some of which have involved acts of violence and vandalism.[2] Revival promises large-scale state investment and the resumption of the unfinished Belene nuclear power plant project – an investment involving Russian companies. At the same time, it advocates deregulation targeting small and medium-sized enterprises, tax relief for families, and the digitalisation of public administration.

Revival calls for a radical shift away from Sofia’s current Euro-Atlantic foreign policy. It proposes a referendum on NATO membership and the renegotiation of EU treaties to reduce the Europpean Union’s role to that of a free trade area.[3] The party is highly critical of Brussels’ migration, energy, and climate policies, and in the European Parliament it belongs to the Europe of Sovereign Nations Group, founded at the initiative of Alternative for Germany. It also seeks closer ties between Sofia and the BRICS countries. Revival is openly pro-Russian. Amid the full-scale war in Ukraine, it opposes any form of assistance to Kyiv, demands the lifting of sanctions against Moscow, and calls for the restoration of bilateral relations. This orientation was underscored in 2025 when the party signed a cooperation agreement with Vladimir Putin’s United Russia, the party which currently governs Russia.

Revival has adopted revisionist positions with regard to other countries in the region. It questions the existence of a distinct Macedonian nation and proposes the unification of North Macedonia with Bulgaria as two ‘Bulgarian states’. It has also voiced territorial claims over southern Bessarabia, a region of Ukraine inhabited by a Bulgarian minority of approximately 130,000 people.

The party’s co-founder and leader is Kostadin Kostadinov, a long-standing former member of the nationalist Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation – Bulgarian National Movement (VMRO–BND). Alongside his party activity, he has worked as an ethnologist focusing on the Bulgarian diaspora and the country’s heritage beyond its borders. He achieved his first political successes with Revival in his hometown of Varna. In addition to his pro-Russian stance, he has previously expressed strong anti-Roma views. In 2022, Kyiv imposed a 10-year entry ban on Kostadinov. At home, he acquired the nickname ‘Kopeykin’ owing to alleged financial ties with the Kremlin.

...imitators of Orbán...

The youngest radical force in the Bulgarian parliament is Morality, Unity, Honour (MECh).[4] It is led by Radostin Vasilev, a former member of various anti-establishment parties who served as Minister of Youth and Sport in Kiril Petkov’s reformist government between 2021 and 2022. Vasilev has admitted that the decision to found his own party in 2024 was inspired by the politics of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. However, the party’s declared ‘Budapest model’ has so far had little tangible impact on its legislative proposals. This is the first parliamentary term in which Sword has had representatives, currently holding 11 seats. During the election campaign, Vasilev gained popularity through his activity on social media, where he promised a constitutional reset and a relentless fight against corruption. He harshly criticised the ruling elites, accusing them of ‘subservience’ to Western countries, and pledged to pursue a ‘genuinely pro-Bulgarian’ foreign policy.

As regards domestic issues, Sword aligns closely with Revival, calling for deep reforms, increased funding for rural regions, the defence of traditional values, and support for small businesses. However, its foreign policy rhetoric is less radical. The party does not advocate Bulgaria’s exit from NATO or the EU, but adopts a sovereigntist stance and rejects federalist ideas. Regarding the war between Russia and Ukraine, Sword promotes a policy of ‘neutrality’. It supports only humanitarian aid for Kyiv, opposes further arms deliveries, and calls for the resumption of economic cooperation with Moscow.

The party is also distinguished by its belief that the state should play a greater role in the economy. Sword advocates, among other things, the nationalisation of the Lukoil-owned refinery in Burgas and the closure of private gambling companies, to be replaced by a state-run monopoly through the national lottery. It also strongly promotes increased social spending, a stance that may appeal to more moderate voters and enable the party to position itself as a less radical alternative to Revival.

...para-environmental nationalists

The smallest radical force in the Bulgarian parliament is Majesty.[5] It initially emerged as a protest movement opposing plans for wind energy development in a small municipality in the east of the country. After achieving success at the local level, it entered the National Assembly in June 2024. However, just a month later, its parliamentary group collapsed due to internal conflicts. The party returned to parliament in 2025 following a correction to the results of the October 2024 elections, ordered by the Constitutional Court after voting irregularities were identified. Mayestat currently holds 10 seats in parliament.

On domestic issues, the party echoes the views of the two other radical factions, highlighting irregularities in state institutions. In foreign policy, it is closer to Sword – advocating neutrality in international politics and adopting a sovereigntist stance, but without questioning Sofia’s membership of the EU and NATO. Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine – even before the movement was formally established – its leader co-organised recurring ‘Marches for Peace’, during which some Kremlin propaganda narratives were repeated and military support for Kyiv was openly opposed.

What sets Mayestat apart from the other radical parties is its strong (para)environmental component. It condemns deforestation and the existence of landfills, and opposes the mass development of renewable energy – particularly wind power – which it claims is harmful to the natural environment. Party activists promote claims about the negative impact of wind turbines on the health of both humans and animals. While they accept the development of solar power, they argue that it should remain the domain of individual prosumers. The party’s environmentalism is selective, however – it rejects EU climate policies and advocates the protection of coal mining.

The central figure in Mayestat is Ivelin Mihaylov, often described as its chief ideologue. He rose to prominence as the founder of the Historical Park near Varna, which presents the history of the Bulgarian state over the centuries. Investigations by the National Security Agency and independent journalists have found that the park operates as a financial pyramid scheme, and that illegal paramilitary groups stockpiling weapons have emerged within its structures. Over time, Mihaylov established parallel institutions in the municipality where the park is located, including bodies responsible for maintaining public order.[6] Media outlets have also suggested that Mihaylov maintains ties with Russian nationalist circles, including the Night Wolves motorcycle club, which is subject to EU sanctions. These revelations have helped Mayestat’s leader cultivate an image among his supporters as a civic activist persecuted by the establishment for promoting patriotic values and criticising the political elite.

Reasons for the radicals’ popularity: political instability…

At the root of the radicals’ success lies the prolonged political crisis that has gripped Bulgaria since 2021. That year, the centre-right GERB party, led by Boyko Borissov and in office since 2009 (with brief interruptions), lost power. Since then, Bulgaria has held seven parliamentary elections and been governed by six different prime ministers – three of them interim. None of these governments lasted a full year.[7] This inability to form a stable executive and the near-permanent election cycle have eroded public trust in state institutions and the political class. Since the beginning of the crisis, an average of 60% of Bulgarians have rated successive governments negatively, while 75% have expressed dissatisfaction with parliament.[8] This disillusionment has also affected attitudes towards the democratic system itself – in 2024, 54% of citizens believed it required major improvements, and 25% considered that it should be completely overhauled.[9]

This crisis of confidence in the institutional order has led part of society to turn towards radical parties. Untainted by the experience of governing, they offer seemingly simple solutions to complex problems, often promoted through social media. While none of these parties openly reject the democratic system, their rhetoric may encourage citizens to question or challenge it. For example, in 2024, 42% of Revival voters supported the introduction of an authoritarian regime.[10]

As a consequence of Bulgarians’ systemic distrust in the political class, civic engagement has declined, creating favourable conditions for newly established parties. Voter turnout in the most recent parliamentary elections was only 39%,[11] compared with 51% at the end of GERB’s rule. This environment allows parties benefitting from a ‘freshness effect’ to enter the National Assembly with markedly fewer votes. In the last election, Sword and Mayestat required only 112,000 and 97,000 votes, respectively, to cross the four per cent threshold. In March 2021, such results would not have secured them parliamentary representation.

...disillusionment with the rule of reformist and anti-establishment parties...

One of the factors that contributed to the growing popularity of the radicals was public disillusionment with the political parties that emerged or gained momentum following the fall of GERB. Among them, the most prominent were the conservative-populist There Is Such a People (ITN) and the liberal, pro-European We Continue the Change (PP). Both parties drew on the legacy of the mass protests of 2020–2021, which criticised the Borissov government for corruption, serving oligarchic interests, and politicising the judiciary. Together with the post-communist Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) and the conservative-liberal Democratic Bulgaria (DB), they formed a government in 2021, led by PP’s Kiril Petkov. ITN soon proved a destabilising force – slowing down reform efforts and ultimately withdrawing its support at a critical moment. Although at the peak of its popularity the party enjoyed support from over 20% of voters, it never regained public trust and now polls only slightly above the electoral threshold. PP’s image also suffered, particularly from its unstable and contradictory coalition with GERB in 2023–2024. Since 2022, the party has been in an alliance with DB.

Polling data on voter support flows show that a portion of the electorate, disillusioned with the ‘first wave’ of anti-establishment and reformist parties, turned to radical forces that combine anti-corruption agendas with nationalist rhetoric. In November 2021, 16% of Revival supporters said they had voted for ITN in a previous election. In October 2022, 17% admitted to previously backing PP – a party that was also the former choice of 19% of those who voted for Mayestat in June 2024. The overlap among anti-establishment forces is also visible at the personnel level. For example, four current Sword MPs previously held the same position as members of ITN.[12]

The nationalist profile of Revival, Sword, and Mayestat may have attracted voters who, during the first two decades of the 21st century, were represented by VMRO–BND and the xenophobic Ataka party. These groups regularly entered parliament and, from 2017, as part of the United Patriots coalition, co-governed in Boyko Borissov’s third cabinet. However, cooperation with the widely criticised GERB government and internal conflicts led to the fragmentation of the traditional far right. Despite repeated attempts to rebuild a broad coalition, these parties have since failed to reach the electoral threshold. In the context of ongoing political instability, VMRO–BND, Ataka, and other smaller parties have lost influence. Nonetheless, the results of successive elections show that nationalist sentiment remains present in Bulgarian society. Today, its main representative is Revival, and to some extent Sword and Mayestat.

...and international climate

Bulgarian radical parties have also been strengthened by global events in recent years. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Revival succeeded in rallying voters who opposed public health restrictions and the so-called ‘green certificates’ issued to vaccinated individuals. Party activists also downplayed the epidemiological threat, which resonated with the attitudes of a portion of the public.[13] All three radical parties have skilfully exploited the war in Ukraine, fuelling long-standing pro-Russian sympathies and sentiments within Bulgarian society.[14] They have also benefited from the broader rightward shift in global politics, particularly after Donald Trump’s return to power. The change in leadership in Washington has brought EU environmental regulations and stricter migration policies under increased mainstream criticism – positions that were previously the domain of marginalised radical groups.

What especially bolsters the popularity of these parties is their opposition to EU energy and climate policies, particularly the shift away from fossil fuels. Coal remains a key resource for Bulgaria, and despite a gradual decline it still accounts for nearly 30% of the country’s electricity generation. Its long-standing role in the energy sector and public resistance to renewable alternatives create fertile ground for radical narratives portraying EU decision-makers as threatening Bulgaria’s energy sovereignty.

Limits of support

Support for Bulgaria’s radical parties is likely to continue growing. The political scene remains unstable and fragmented, leading part of the population to identify with demands for sweeping institutional change. Low voter turnout confirms that there remains significant potential to mobilise inactive citizens – a task in which radical parties have already seen some success. They are also likely to benefit from potential setbacks facing reformist forces, such as the corruption scandal involving PP activists in Sofia in June 2025. Such incidents may allow nationalist parties to present themselves as the only true political alternative, untainted by major scandals.

Another factor with the potential to bolster support for radical parties is Bulgaria’s planned adoption of the euro in 2026, a move opposed by as much as half the population, according to some polls.[15] In parliament, only Revival, Sword, and Mayestat clearly object to this decision. The expected short-term rise in prices following the introduction of the common currency is likely to trigger public discontent, potentially bringing further support to these parties. However, the street mobilisation efforts led by these groups have so far been limited. At most, only a few thousand people participated in demonstrations in defence of the Bulgarian currency.

It is difficult to determine the upper limit of support for radical parties in Bulgaria. A key reference point for nationalist forces remains the result of Ataka leader Volen Siderov, who secured nearly 650,000 votes (24%) in the second round of the 2006 presidential election. Today, it appears unlikely that any single radical party could replicate that result, and the combined total of the radical bloc in the most recent parliamentary election was about 100,000 votes lower (see chart). A major test of the nationalist-anti–corruption camp’s potential will come with the 2026 presidential election, where the votes of its supporters may be consolidated behind a single candidate – possibly Revival leader Kostadin Kostadinov.

Revival will remain the main representative of the radical electorate. According to recent polls, it enjoys support of between 11% and 14%, at times making it the second most popular party in Bulgaria. It has a stable voter base of around 300,000 people, but its exclusionary rhetoric limits the potential to expand support to a level that would enable it to govern or co-govern the country. Its strongly pro-Russian and anti-Western stance also works against it, as this attitude does not align with the views of the majority of the political class or the wider public.[16] Attempts to soften the party’s narrative or openly cooperate with the establishment currently appear unlikely and would undermine its image as a disruptive political force.

The position of Sword and Mayestat remains uncertain. In opinion polls, the former performs better, presenting itself as a more moderate nationalist option. However, it may face competition in the future from President Rumen Radev, whose second term ends in January 2027. The head of state is reportedly considering the formation of his own political movement, aimed at attracting more moderate sovereigntist voters. It cannot be ruled out that the parties led by Vasilev and Mihaylov will prove to be short-lived products of a period of instability – similar to other anti-establishment groups that briefly entered parliament after 2021 but failed to maintain their presence.[17]

Conclusions and prospects

Although Revival, Sword, and Mayestat currently have no realistic prospects of gaining full power, their rhetoric continues to influence Bulgarian politics. Mainstream parties are under constant pressure from the radicals and occasionally adopt elements of their agenda. These groups are also shifting the boundaries of public debate, which may indirectly encourage the rest of the opposition – particularly the PP–DB alliance – to adopt a more confrontational stance towards the government. Nationalist parties are also likely to fuel the escalation of historical and identity-related disputes with North Macedonia. This would further complicate Skopje’s efforts to implement the constitutional amendments on the Bulgarian minority promised under the 2022 agreement – measures necessary to begin EU accession negotiations.[18]

At present, it does not appear that the radical parties pose an immediate threat to Bulgaria’s pro-Western orientation. While they may call for restoring relations with Moscow or oppose greater financial commitments within NATO, it is unlikely they will find sufficient parliamentary support to implement such policies. On the contrary, their growing popularity is motivating mainstream parties to cooperate on the core pillars of foreign policy. One example of such efforts was the formation of the ‘Euro-Atlantic’ minority government led by Rosen Zhelyazkov in January 2025, which brought together ideologically divergent parties such as GERB, BSP, and ITN.[19] At the same time, the strong presence of radicals allows the ruling bloc to portray itself – especially in the international community – as the guarantor of Sofia’s pro-Western course and a bulwark against pro-Russian tendencies. Boyko Borissov has been at the forefront of this narrative, using GERB’s membership in the European People’s Party to rebuild his international standing. He is seeking to return to favour within the EU mainstream, where trust in him was severely damaged by corruption scandals and the mass protests against his rule in 2020–2021.

The three radical parties are jointly attempting to topple Zhelyazkov’s government. With a combined total of 54 MPs, they have the numbers to file successive motions of no confidence,[20] primarily as a means of obstructing parliamentary work. None of the four attempts made so far has stood a realistic chance of success. The radical forces frequently vote together against government proposals, and any instance in which one of the parties supports a government initiative is met with accusations from the others of betraying anti-establishment ideals. These tensions reflect the competition among the parties for a largely overlapping, ideologically similar electorate. Most conflicts arise between Revival and Mayestat, whose leaders accuse each other of behind-the-scenes cooperation with mainstream parties – particularly GERB – despite occasional past collaboration between Kostadinov and Mihaylov.[21] Sword maintains a more moderate tone, but its members have also implied the existence of a tacit agreement between Revival’s leader and Borissov, allegedly serving the mutual interests of both parties.

The far right’s ability to form a broad nationalist coalition remains limited. Such an alliance would be particularly disadvantageous for Revival, which already holds a consolidated position on the political scene with a stable voter base. Nor would it benefit the two newer parties, which have capitalised on their novelty to attract nationalist voters disillusioned with or opposed to Kostadinov’s party. That said, in the event of another snap election, a potential alliance between Sword and Mayestat cannot be ruled out – particularly if their polling results prove disappointing. Despite the existing tensions among them, all three radical parties are likely to continue coordinated attempts to topple the government, possibly in cooperation with PP–DB, thereby further contributing to the destabilisation of Bulgaria’s political landscape.

Chart. Number of votes cast for Bulgarian nationalist parties, 2017–2024

Source: Bulgarian Central Election Commission (CIK), cik.bg.

[1] See J. Nowinowski, ‘Bulgaria joins the eurozone in 2026: a success for the government amid public concerns’, OSW, 10 July 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[2] In February 2025, a protest in Sofia ended with the vandalism and an attempted arson attack on the European Commission building.

[3] At the same time, Revival opposes Bulgaria’s membership in the Schengen Area, which was secured on 1 January 2025, citing concerns over uncontrolled immigration.

[4] The party most commonly uses the acronym for Morality, Unity, Honour (Морал, Единство, Чест), which also forms a wordplay (МЕЧ – Sword). According to its leader, the name symbolises radical methods of combating injustice in Bulgarian politics.

[5] The party’s original name is Velichie (Величие), which is also sometimes translated as Greatness.

[6] Й. Запрянов, ‘Ветринска народна република: "Исторически парк" се въоръжава’, Капитал, 30 April 2024, capital.bg.

[7] For more see Ł. Kobeszko, ‘A country of interim governments. The political crisis in Bulgaria and the attempts to solve it’, OSW Commentary, no. 600, 3 June 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[8] Author’s own estimates based on ‘Обществени нагласи спрямо основните институции, партии и актуални теми (май 2025)’, Trend, May 2025, rcdtrend.bg.

[9] Public attitudes towards corruption in Bulgaria and the anti-corruption actions of the Bulgarian Government, Basel Institute on Governance, September 2024, baselgovernence.org.

[10] Only 46% of these voters expressed support for liberal democracy. See ‘Демокрация или комунизъм: 2% българи искат да живеят в държава с военен режим’, bTV Новините, 21 August 2024, btvnovinite.bg.

[11] The turnout was the lowest during the combined parliamentary and European elections in June 2024, reaching just 34%.

[12] Gallup International Balkan surveys conducted from 2021 to 2024.

[13] Bulgaria recorded the lowest COVID-19 vaccination rate in the EU – with only about 30% of the population vaccinated.

[14] These stem from historically close relations between the two countries. In the 19th century, Tsarist Russia supported Bulgarian aspirations for independence, and during the communist era Bulgaria was the Soviet Union’s closest ally in the Eastern Bloc, even considering the option of becoming the USSR’s sixteenth union republic. After 1989, relations were maintained through economic cooperation – particularly in the fields of energy and tourism – as well as through cultural and religious ties.

[15] В. Минков, ‘Българите остават разделени за еврозоната’, Капитал, 28 May 2025, capital.bg.

[16] Over 70% of citizens support EU membership, and since 2022, trust in the importance of NATO has risen to 62%. See GLOBSEC Trends 2025: Ready for a New Era?, GLOBSEC, 14 May 2025, globsec.org.

[17] This refers to the anti-corruption movement Rise Up! Get Out, Bandits! (which held seats in two parliamentary terms) and the national-conservative, pro-Russian Bulgarian Progress (which served one term).

[18] See Ł. Kobeszko, M. Szpala, ‘Krucha ugoda Macedonii Północnej z Bułgarią’, OSW, 22 July 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[19] See Ł. Kobeszko, ‘Bulgaria: a 'grand coalition' government’, OSW, 17 January 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[20] To file a motion of no confidence, signatures are required from at least one fifth of the deputies, i.e. Members of Parliament.

[21] Kostadinov praised the Historical Park, while Mihaylov sold his books there. They also organised joint live broadcasts on social media.