The little ‘Big Brother’ is still watching. Montenegro’s response to Serbia’s influence

Independent since 2006, Montenegro continues to pursue a Euro-Atlantic foreign policy direction, although it remains within the sphere of Serbian political, economic, cultural, and media influence. This is manifested in the tangible progress made over the past year in accession negotiations with the EU. The prospect of membership enjoys the support of three-quarters of the population and constitutes both a key objective and the main unifying factor of the governing coalition formed in 2023. However, Montenegro’s accession ahead of Serbia would be perceived as a political setback for Belgrade. It would not only reduce its influence in a state whose sovereignty is at times questioned by Serbian politicians, but would also increase the pressure on Serbia to implement domestic reforms – something the Serbian government is reluctant to do. Belgrade has a range of tools to influence public sentiment in Montenegro. It exerts influence on local politics, including through support for Serb minority parties, and also provides funding to the Orthodox Church, as well as to NGOs and affiliated media outlets. In an effort to undermine Podgorica’s success and keep it within its sphere of influence, Belgrade may attempt to use these instruments to destabilise the situation in its southern neighbour.

Acceleration of Podgorica’s EU integration efforts

After 2023, Montenegro intensified its EU accession negotiations. This was driven by the centrist, pro-European Europe Now! Movement (PES), which first promoted Jakov Milatović to the presidency, and subsequently won the parliamentary election.[1] Milojko Spajić became Prime Minister, and his government adopted a reform plan which, in July 2024, received a positive assessment from the European Commission for fulfilling the initial benchmarks under chapters 23 and 24 of the accession negotiations (the so-called IBAR).[2] In December 2024, Montenegro closed three negotiation chapters, thus ending the stagnation in the process that had lasted since 2017. The government’s objective is to conclude talks with the EU by 2026 and attain membership by 2028.

Spajić’s cabinet succeeded in returning to the path of European integration and partially restoring political stability, which had been disrupted in 2020 following the fall from power of the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), a post-communist party that had governed for 30 years. Montenegro was granted EU candidate status in 2010 but failed to implement key reforms, managing to close only three negotiation chapters over the following decade. No improvement came during the 2020–2023 period either, as internal coalition disputes prevented the new ruling parties from delivering on their promises to improve the functioning of the judiciary and to tackle corruption and organised crime.

The current authorities are attempting to reconcile an ambitious reform agenda and progress in European integration with the desire to maintain good relations with Serbia. Their focus lies on economic and infrastructural cooperation with their neighbour, while avoiding sensitive ethnic issues – a task that is far from easy. Many Serbian politicians remain sceptical of Podgorica’s sovereignty, viewing Montenegro as a ‘Serbian state’ that should remain within Belgrade’s sphere of influence, or even aspire to political reunification. The existence of an independent Montenegrin national identity is also relativised, often being questioned or regarded as merely a variant of Serbian identity.[3]

Montenegrin-Serbian relations: from crisis to a new opening

The policy of warming relations with the northern neighbour, currently pursued by Spajić’s government, continues the approach initiated by the cabinet of Dritan Abazović – leader of the liberal United Reform Action (URA) party – which was formed in spring 2022.[4] These steps include, among other things, the appointment of Serbia’s ambassador to Podgorica (in February 2024) and the decision to send a Montenegrin diplomatic representative to Belgrade (a year later), which brought an end to a period of deep crisis in bilateral relations that had lasted for over four years. Although full stabilisation and normalisation of relations are still hindered by incidents related to historical politics (such as Podgorica’s support for the 2024 UN resolution recognising the Srebrenica massacre as genocide, which was criticised by Serbia), this policy can be considered effective. It is worth noting that relations between the two capitals have often been tense ever since Podgorica declared independence following the 2006 referendum.[5]

The father of the independence movement was Milo Djukanović – leader of the DPS, who served three terms as Prime Minister and one term as President between 2006 and 2023.[6] He was an advocate of building a Montenegrin identity distinct from that of Serbia. Podgorica sought to limit symbolic ties with Belgrade by promoting the Montenegrin language as separate from Serbian (despite their full mutual intelligibility and only minor differences), as well as by emphasising its own historical heritage. In foreign policy, the socialists pursued a Euro-Atlantic integration path, while remaining open to economically beneficial cooperation with Russia and China. They also maintained favourable relations with Belgrade, although they were unable to avoid crises, such as the one triggered by Podgorica’s recognition of Kosovo’s independence in 2008.[7]

Relations were particularly good after 2012, when the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) came to power in Belgrade. In 2013, Djukanović, then serving as Prime Minister, paid an official visit to the Serbian capital – his first since the declaration of independence. At the time, the DPS leader also enjoyed good personal relations with SNS leader Aleksandar Vučić (though the two eventually drifted apart), who became Prime Minister of Serbia in 2014 and has held the office of President since 2017. Both politicians developed a similar model of governance based on clientelist networks, ties to the criminal underworld, and the consolidation of power around their respective parties.

Relations with Serbia deteriorated after Montenegro joined NATO in 2017, despite Belgrade’s official statements of respect for its neighbour’s decision. The Serbian authorities sought to strengthen their influence in the Adriatic country, while Podgorica endeavoured to resist these efforts. This coincided with President Vučić intensifying his policy of protecting the interests of Serbs in neighbouring countries. According to the 2023 census, 205,000 Serbs live in Montenegro, making up 33% of the country’s population.[8] Meanwhile, 43% of the population declare Serbian as their mother tongue, while 35% use Montenegrin, which is formally the sole official language. In practice, however, Serbian, Albanian, Bosnian, and Croatian also hold the status of ‘languages in official use’, allowing them to function alongside Montenegrin in administrative contexts.

A new chapter in Montenegrin–Serbian relations began in 2020, when the socialists lost power in Podgorica after nearly three decades. However, hopes for improved relations quickly gave way to renewed tensions. The new government was headed by Zdravko Krivokapić, a politically non-aligned leader of protests in defence of religious sites. He formed a cabinet made up of experts, supported, among others, by the Serb minority bloc, on whose electoral list he had stood. Despite expectations from circles close to Belgrade, Krivokapić pursued a relatively assertive policy towards the larger neighbour. In 2021, the Montenegrin parliament – the Skupština – adopted a resolution recognising the massacre committed by Bosnian Serbs in Srebrenica in 1995 as genocide. This move provoked widespread criticism from Serbian pro-government media. Krivokapić also contributed to the dismissal of the justice minister, who had denied the genocide. This led to the withdrawal of support from the Serb minority party and the loss of his parliamentary majority.

Montenegrin Serbs: between Belgrade and domestic politics

The foreign policy orientation of parties representing Montenegrin Serbs remains ambivalent, although over the years it has evolved from openly anti-Western to (at least nominally) pro-European. The main representative of Montenegro’s largest ethnic minority is the right-wing coalition For the Future of Montenegro (ZBCG), in which the most prominent roles are played by Andrija Mandić’s New Serbian Democracy and Milan Knežević’s Democratic People’s Party. During the first decades of independence, the Serb minority party bloc (under various names) was the main opposition force to the DPS and Djukanović, consistently garnering between 15% and 25% of the vote. It opposed Montenegro’s accession to NATO, recognition of Kosovo’s independence, and the imposition of sanctions on Russia in 2014 and 2022. It advocated a foreign policy approach aligned closely with Belgrade, based on strategic balancing. While its politicians did not oppose EU integration and supported the use of EU funds, they simultaneously called for enhanced cooperation with China and Russia. They also criticised the decision on independence, favouring the maintenance of a political union with Serbia.

In the face of Belgrade’s increasing focus on strengthening ties with ethnic Serb communities in neighbouring countries and the gradual cooling of relations with Podgorica after 2017, Montenegrin Serbs could count on greater support from Serbia. The main beneficiary of this support was Mandić, who from 2016 met with Vučić regularly – at least once a year (with the exception of 2022) – and was invited to state and party ceremonies in Serbia. His connection to a Belgrade patron enabled him to build an image as the leader of the Serb minority in Montenegro and its chief defender against alleged persecution by Podgorica. The end of the DPS government in 2020 appeared to mark the end of the isolation of Serb minority parties and to offer an opportunity to implement at least some of their demands, including the establishment of Serbian as an official language, the legalisation of dual citizenship,[9] and changes to national symbols.[10] These hopes were not realised during the tenure of Prime Minister Krivokapić, who had promised to improve relations with Serbia; paradoxically, it was the liberal cabinet of Abazović that made decisions more closely aligned with their agenda.

Since the presidential campaign in 2023, there has been a gradual shift in the narrative of the Serbian minority party. During his bid for the presidency, Mandić avoided identity-based disputes and presented himself as a politician open to dialogue. Similar rhetoric was maintained ahead of the parliamentary election, in which ZBCG secured 13 seats in the 81-member Skupština. In exchange for supporting Spajić’s government, Mandić was awarded the prestigious role of Speaker of Parliament. Following a cabinet reshuffle in summer 2024, representatives of the Serbian minority formally joined the Council of Ministers, taking over leadership of the ministries of education, infrastructure, transport, tourism, and spatial planning. The ZBCG votes in line with the parliamentary majority, supporting further integration with the EU. The desire to maintain their current position and remain part of the political mainstream may have led members of the bloc to soften some of their more radical demands, particularly their pro-Russian and anti-Western tendencies, which stand in contrast to the views held by the majority of society.

Serbia’s soft power instruments in Montenegro

Belgrade has extensive means of influencing its southern neighbour through instruments of soft power. In Montenegro, there is a network of approximately 20 non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that promote Serbian identity in areas such as culture, education, religion, sport, and the media, with the support of Serbian institutions. A typical instrument of financial assistance comes in the form of annual grants, distributed via the Office for Cooperation with the Diaspora and Serbs in the Region. However, the total value of these grants remains relatively modest, ranging from €21,000 in 2016 to €104,000 in 2014. The most recent tranche of support in 2024 amounted to €80,000.[11]

Larger sums are allocated to such organisations through one-off grants from the Serbian state budget. This was the case in 2017, when Vučić awarded a targeted subsidy of €3.4 million for the construction of the Serbian House in Podgorica. In 2023, this institution funded the campaigns of Mandić and the ZBCG in the presidential and parliamentary elections. According to media reports, between 2014 and 2020 nearly €2 million was also directed to the Serb National Council of Montenegro and Matica Srpska in Nikšić (the country’s second-largest city).[12] In 2021, €2 million from Belgrade’s budget was allocated to infrastructure investments in Nikšić, which is co-governed by a coalition of Serbian minority parties. Local media have also reported instances of vote-buying in favour of Serbian groups during local elections by visiting SNS activists.[13]

An important element of Serbia’s soft pressure tools is the Serbian Orthodox Church (SOC) and its subordinate diocese, the Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral (MML), to which an estimated 62% of citizens belong.[14] The Church enjoys high public trust in Montenegro (51%)[15] and actively participates in the country’s public life. The MML has also received grants from the authorities in Belgrade. According to Montenegrin media, the total value of this support between 2014 and 2020 may have reached as much as €4.6 million.[16] In an attempt to curb the growing influence of the Church, in December 2019, at the initiative of the DPS, parliament passed a law on freedom of religion and belief which, among other things, allowed the state to confiscate property older than 100 years belonging to the MML if ownership could not be properly documented. This decision sparked mass protests in defence of the churches and criticism from Serbian politicians and media, who accused Podgorica of an attack on Serbian identity in Montenegro.

Despite Serbia’s financial assistance and the SOC’s authority over the MML, Montenegrin hierarchs pursue a relatively independent policy. Leading in this regard was Metropolitan Amfilohije, who died in 2020 and had frequently criticised Vučić, including over his actions concerning Kosovo. At the same time, although the MML is not directly controlled by Belgrade, it often echoes its narrative on international matters, and at times goes even further, adopting an openly pro-Russian stance. Amfilohije’s successor, Metropolitan Joanikije II, in 2022 highlighted alleged persecution by Kyiv of the faithful of the Moscow Patriarchate in Ukraine. Since the outbreak of the full-scale war, he has visited Russia twice and in 2025 hosted Russian hierarchs in Podgorica. The Church also leverages its authority in political affairs, offering direct support to the ZBCG and legitimising Vučić’s regional policy. It has actively engaged in campaigns promoting Serbian identity, for example in the context of the 2023 national census.

Serbian influence on Montenegrin public debate is facilitated by the linguistic and cultural closeness of the two countries. However, the lack of available data on the popularity of Montenegrin media makes it difficult to determine the exact scale of the influence exerted by Serbian news channels. 47% of Montenegrins state that they ‘often’ or ‘always’ watch television channels from countries in the region in a language they understand.[17] For instance, nearly 33% of respondents admitted to regularly following programming from the local branch of Pink TV, which in Serbia is one of the most prominent pro-government mass media outlets.[18] Thanks to local telecommunications providers, it is easy to access a broader selection of Serbian channels. This cross-border media influence is also evident online. According to a report by the Digital Forensic Centre, the most popular Serbian news websites in Montenegro in 2021–2022 were Alo, Espreso, Informer, Kurir, and Srbija Danas. All of them belong to a group of tabloids supportive of the authorities in Belgrade. During the analysed period, these outlets sought to discredit Montenegro by highlighting the instability of its political scene, the alleged discrimination against the Serbian minority, and problems with organised crime.[19]

Serbia’s soft power tools also include certain Montenegrin media outlets, due in part to their ownership structure. Of the five television stations with the highest level of public trust, three are in Serbian hands. Serbian capital finances both pro-European channels (TV Vijesti, Nova M) and those supportive of Belgrade and Serbian minority parties (Prva TV). During the 2023 election campaign, Prva and Adria TV allocated the most free airtime to ZBCG politicians (50% and 39%, respectively).[20] Both stations also promote a pro-Russian narrative, downplaying the 2022 aggression against Ukraine. Smaller-scale websites linked to Serbian NGOs also serve as conduits for Moscow’s propaganda.

The economy: former ties and current influence

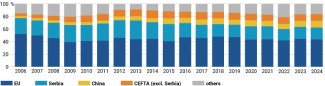

Serbia has traditionally maintained a strong capital presence in Montenegro, stemming from years of co-existence within a shared state, cultural proximity, and family ties, among other factors. Serbs lead the statistics for foreign subsidiaries[21] as well as foreign direct investment (FDI), the value of which reached €125 million in 2023. This makes Serbs the most active nationality in investing in Montenegro (accounting for 15% of total FDI in 2023), even surpassing Russians,[22] who have traditionally been frequent investors in coastal towns (see Chart 1). The structure of Serbian investments has changed significantly over the years. Since 2018, the share of Serbian capital in Montenegrin companies and banks has declined, while private involvement in the real estate sector has increased.

Chart 1. Largest foreign direct investors in Montenegro, 2006–2023 (according to their share in FDIs)

Source: Central Bank of Montenegro, cbcg.me.

Serbian private enterprises are particularly active in Montenegro in the tourism, pharmaceutical, and food processing industries, as well as in the energy sector. Key Serbian state-owned entities also operate in the country. The largest mobile telecommunications provider, Mtel, holds a 38% market share and is owned by the state-run operator Telekom Srbija (51%) and its subsidiary Telekom Srpska (49%). Serbia’s national electricity grid operator, Elektromreža Srbije, owns a 15% stake in its Montenegrin counterpart, Crnogorski elektroprenosni sistem. Consequently, it contributes to stabilising Montenegro’s electricity production, which relies heavily on hydropower plants (accounting for 44% of electricity generated), the output of which is vulnerable to rainfall shortages.

As part of bilateral cooperation, Serbia has expressed its willingness to participate in joint infrastructure projects, such as the construction of a motorway from Belgrade to the Adriatic coast and the development of new border crossings. High hopes are pinned on the project to modernise the railway line connecting the Serbian capital with the Montenegrin coastal town of Bar, for which both countries are seeking EU funding. In the past, Serbian decision-makers pledged to create new jobs in northern Montenegro, a region with a significant Serbian minority population; however, these promises have yet to materialise.

Serbia is Montenegro’s most important economic partner. The value of bilateral trade in 2024 amounted to €884.1 million, accounting for 19% of the Adriatic country’s total trade (see Chart 2). However, the relationship is asymmetrical, as Montenegro primarily imports goods from Serbia (resulting in a negative trade balance in 2024 of -€515.1 million). It mainly imports consumer goods: alcohol, beverages, cereal products, and livestock. Montenegro, in turn, exports pharmaceuticals, electricity (in cases of surplus production), and hard coal to Serbia.

Chart 2. Montenegro’s most important trade partners, 2006–2024

Source: Statistical Office of Montenegro – MONSTAT, monstat.org.

Official trade statistics may not fully reflect the extent of Podgorica’s ties with Belgrade due to exchanges taking place within the so-called grey economy. According to estimates, the informal sector accounts for 20–30% of the Adriatic state’s GDP.[23] Owing to its geographical location, Montenegro serves as a drug trafficking hub for the Western Balkans and is also a key transit point for the smuggling of weapons, fuel, and cigarettes, with the main centre being the port of Bar. Montenegro’s two largest criminal groups – the Škaljari and Kavač clans – hold strong positions and maintain networks of connections in Serbia. Members of these rival gangs have repeatedly been shown to have links with Serbian football hooligan groups and elements of the country’s political elite.

Conclusions...

Nineteen years after gaining independence, Montenegro remains subject to strong Serbian influence in political, economic, and cultural spheres. Serbia continues to be its most important trading partner and the leading foreign investor. Serbian capital is increasingly invested in the real estate sector, which offers limited potential for influencing internal processes. The implementation of joint infrastructure investments, such as the modernisation of the Belgrade–Bar railway line, will primarily depend on the ability to secure EU funding. A key challenge for Podgorica will be tackling Montenegrin–Serbian organised crime, which hampers reform efforts and tarnishes the country’s international reputation.

It should be expected that representatives of the Serbian minority bloc within the government in Podgorica will continue to demand the expansion of minority rights, calling for the legalisation of dual citizenship and for Serbian to be recognised as an official language on an equal footing with Montenegrin. Attempts to obstruct the reform process cannot be ruled out, which could lead to a slowdown in EU accession negotiations. The future actions of the ZBCG coalition will depend on political developments in Serbia, where the government has come under challenge from mass protests that have been ongoing since early November 2024.[24] Signs of divergence are already visible between the two main political leaders of Montenegro’s Serbs: in the face of the crisis, Knežević supports Vučić, while Mandić distances himself from the authorities in Belgrade and refuses to comment on the situation in Serbia.

The reforms that have led to progress in the negotiations are being implemented with the involvement of Serbian minority parties that form part of the ruling coalition. This presents a certain paradox, as these groups were long associated with anti-Western narratives on Montenegro’s political scene. However, since assuming a role in governance, they have not questioned the country’s pro-European course, have voted in line with the parliamentary majority, and have toned down their radical rhetoric. Despite adopting a conciliatory strategy, the Serbian minority parties do not constitute a stable element of the ruling coalition in Montenegro. Since the country gained independence, their political activity has cast doubt on the sincerity of their pro-European views. It also enables the opposition, centred around the Socialists, to discredit Spajić’s cabinet by accusing it of acting in alignment with Serbia’s interests. The presence of the ZBCG in the government appears to suit Belgrade, as it enables the destabilisation of internal affairs in the neighbouring state. On the other hand, holding five ministerial posts and the position of Speaker of Parliament undermines the claim that Serbs in Montenegro face political discrimination.

...and threats to the accession process

The need for even a symbolic success for Brussels, along with its determination to counter Chinese and Russian influence in the Western Balkans, means that Montenegro now faces a genuine prospect of joining the EU. Over the past year, Podgorica has made tangible progress in accession negotiations, and the goal of membership enjoys strong public support. The European agenda is also reinforced by the ‘civic’ nature of the ruling coalition, which includes Serbian, Bosnian, and Albanian minority parties. A window of opportunity is being opened by the European Commission, which has signalled its readiness to admit a new EU member during its current term (until 2029), potentially ending the stagnation in the enlargement process that has persisted since 2013.

Podgorica’s progress in accession negotiations undermines Belgrade’s image, as Serbian leaders have long claimed that EU enlargement in the Western Balkans must begin with Serbia as the region’s leader. In an effort to discredit its neighbour’s success and keep it within its sphere of influence, Belgrade may attempt to destabilise the situation in Montenegro by increasing financial and propaganda support for the network of Serbian NGOs and their affiliated media outlets. The aim of such actions would be to reach segments of society harbouring anti-Western or anti-Atlanticist sentiments.[25] These organisations are also likely to challenge the separate nature of Montenegrin national identity by promoting Serbian historical and cultural heritage. Montenegrins are also likely to be influenced by the Orthodox Church and its leadership in Belgrade, which may play a role in shaping future electoral processes. It is expected that Orthodox hierarchs will continue to express pan-Slavic and pro-Russian views, promoting Kremlin-aligned narratives.

[1] See Ł. Kobeszko, ‘Montenegro elections: the Socialists defeated, the changes continue’, OSW, 14 June 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[2] The IBAR (Interim Benchmark Assessment Report) evaluates the periodic readiness of a candidate country to implement key reforms required by the EU in the area of the rule of law. A positive assessment is necessary for the closure of subsequent negotiation chapters.

[3] According to surveys, 22% of Montenegrin citizens do not believe in the existence of a Montenegrin identity independent of the Serbian one – see ‘CGO: Crnogorski identitet nesporan za 72% njenih građana, crnogorski jezik priznaje 63.5%’, Portal Analitika, 4 November 2023, portalanalitika.me.

[4] His first foreign trip was to Belgrade, where he announced a reset in relations with Serbia. He expressed support for Montenegro’s accession to the Open Balkan initiative (also known as Mini-Schengen), promoted by Vučić, which effectively duplicated existing regional cooperation frameworks supported by the EU. He also signed the so-called Basic Agreement, recognising the special status of the Serbian Orthodox Church on the Adriatic. This led the Socialists to withdraw their support for his cabinet.

[5] 55.5% of the voters supported independence. The turnout was 86%.

[6] He also held these two posts prior to 2006, when Montenegro was a republic within a state union.

[7] As a result of this decision, Belgrade declared Montenegro’s ambassador persona non grata, prompting a reciprocal response from Podgorica. Neither state had a representative at the highest diplomatic level for almost a year.

[8] The number of ethnic Montenegrins is 256,000, accounting for 41% of the population. Other nationalities in the country’s ethnic mosaic include Bosnians, Albanians, Russians, and Croats – see Stanovništvo Crne Gore prema nacionalnoj, odnosno etničkoj pripadnosti, vjeri, maternjem jeziku i jeziku kojim se uobičajeno govori. Popis 2023. godine, MONSTAT, 15 October 2024, monstat.org.

[9] Montenegro permits dual citizenship if granted prior to 2006 or whenever a relevant bilateral agreement is in place. No such agreement has been signed with Serbia.

[10] The proposed new version of the national flag featured the Montenegrin double-headed eagle against the backdrop of the Serbian tricolour flag.

[12] N. Zečević, ‘Srpskoj kući, SNS-u i Matici srpskoj od Vučića skoro šest miliona eura’, Pobjeda, 3 October 2020, pobjeda.me.

[13] Political corruption allegedly occurred in 2021 in Nikšić and a year later in Budva; Inostrani uticaji na izborni proces u Crnoj Gori 2016-23. Godine. Prvi Dio, Centar za demokratsku tranziciju, 13 May 2024, cdtmn.org.

[14] The Montenegrin population census did not record information on the citizens’ religious affiliation. The available statistics are based on survey estimates. See Gdje je crnogorsko društvo 16 godina od obnove nezavisnosti?, Centar za demokratiju i ljudska prava, September 2022, cedem.me.

[15] Političko javno mnjenje Crne Gore, mart 2024, Centar za demokratiju i ljudska prava, March 2024, cedem.me.

[16] ‘Za profesionalno srbovanje sedam miliona eura, a crkvi 4,6 miliona’, CdM, 30 September 2020, cdm.me.

[17] Ispitivanje navika i stavova slušalaca i/ili gledalaca televizijskog i radijskog sadržaja u Crnoj Gori, Agencija za elektronske medije Crne Gore, December 2022, amu.me.

[18] ‘Mediji u Crnoj Gori u očima građana i novinara’, Centar za građansko obrazovanje, 17 June 2021, cgo-cce.org.

[19] Monitoring srbijanskih medija 2021/22, Digitalni forenzički centar, October 2022, dfc.me.

[20] Parlamentarni izbori 2023. Izvještaj o finansiranju izbornih kampanja, MANS, November 2023, mans.co.me.

[21] Serbs account for 21% of all iFATS. See Statistika stranih filijala – saopštenja, Uprava za statitstiku Crne Gore – MONSTAT, 2013–2023, monstat.org.

[22] Since 2022, Russians have gradually scaled back their business activity in Montenegro. Despite this, they remain an important investor in the country and account for 2% of its population (12,800). Although Podgorica joined EU sanctions against Russia in 2014 and 2022, Russian citizens are still permitted to stay in Montenegro for 30 days without a visa.

[23] The Montenegrin Ministry of Finance estimates the size of the country’s so-called grey economy at 20.6% of GDP. See ‘Predlog programa za suzbijanje neformalne ekonomije 2024–2026 – mišljenje Ministarstva finansija’, Vlada Crne Gore, 6 June 2024, gov.me. Non-governmental organisations estimate it at approximately 30% – Rasvjetljavanje ekonomije u sjeni. Istraživanje neformalne ekonomije u četiri države Jugoistočne Europe, Centar za politike i upravljanje, Sarajevo 2020, cpu.org.ba, after: web.archive.org.

[24] See M. Szpala, ‘Protests in Serbia: a crack in Vučić’s system of political dominance’, OSW, 20 December 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[25] 44% of Montenegrins would vote for leaving NATO, and 46% of them would prefer to remain in the Alliance – after: The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2023, NATO, 14 March 2024, nato.int.