A campaign without elections. Ukraine’s political landscape in the fourth year of the war

For several months, Ukraine has seen increased political activity from both the government and the opposition. Statements by the US president expressing a desire to swiftly negotiate a Ukrainian-Russian ceasefire, which could pave the way for the lifting of martial law and the holding of elections, have led to an intensified struggle for public support. This is happening despite the continued political and social consensus within the country that voting should not be organised as long as hostilities are ongoing. The outcome of the active phase of the war will be crucial for the prospects of potential candidates and parties.

Volodymyr Zelensky’s assertive responses to Donald Trump’s hostile actions and statements regarding Ukraine have led to a shift in voter sympathies and trust in politicians. So far, the Ukrainian president has been the main beneficiary of this trend, with citizens once again rallying around him; however, it is difficult to assess how long this tendency will persist. It appears that an evaluation of the country’s preparations for defence and Zelensky’s wartime leadership will form the central theme of the future campaign. Emerging divisions between those who have remained in the country and those who have left, as well as between those who have fought and those who have not, will also play a significant role. However, it remains unclear how these divisions will influence the political sympathies of a society undergoing rapid change as a result of the war.

Legal and political conditions for holding elections

Under Ukrainian law, elections cannot be held while martial law is in force: parliamentary elections are prohibited by the constitution, and presidential elections by the Law on the Legal Regime of Martial Law. There is also a strong public consensus,[1] on this matter: 78 per cent of the population oppose holding elections before the end of the war.[2] A ceasefire with Russia could open the door to voting, as it would likely lead to increased domestic pressure not to extend martial law, along with pressure from across the Atlantic. The US administration has repeatedly questioned President Zelensky’s electoral mandate, suggesting that he no longer enjoys public support, or even labelling him a dictator, as President Donald Trump has done.[3] Such remarks echoed the Kremlin’s recurring demands for elections to be held in Ukraine. This created the impression of coordinated pressure on Ukraine, aimed at ousting the incumbent president, with whom the US leader had previously clashed,[4] and at negotiating a peace agreement with a more conciliatory politician, even though at present the chances of such a figure winning democratic elections in Ukraine appear slim. According to media reports, Trump’s associates have even held meetings with opposition figures such as Petro Poroshenko and Yulia Tymoshenko,[5] possibly to gauge their readiness to organise an election.

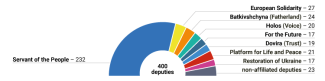

The intensifying political rivalry is driven by external factors and the growing dysfunction of the current political arrangement. This is reflected in the situation in the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. In 2019, the presidential party Servant of the People (SN) won the elections and secured 254 parliamentary seats, becoming the first party in the country’s history to achieve an absolute majority. However, this majority has long been a nominal one. Although the party formally has 232 members, the number of those who participate in voting rarely exceeds 170 to 180. Most laws are passed with the support of deputies from oligarch-affiliated parties such as Dovira and For the Future, as well as from the Opposition Platform – For Life (OPZZh), which was banned in 2022.[6]

The informal and circumstantial coalition with these parties stems from two factors: the instrumental treatment of deputies, which has led to declining discipline within SN,[7] and the departure of 22 SN deputies critical of the president, who joined the inter-factional group Reasonable Politics, founded by Dmytro Razumkov, former Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada[8]. Batkivshchyna, led by former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, and European Solidarity (ES), headed by former President Petro Poroshenko, remain the main opposition forces, although both often support the government’s legislative initiatives related to European integration.[9]

Chart: Distribution of seats in Parliament as of 23 April 2025

Source: The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine.

Demand for new political forces

According to a survey by the Razumkov Centre, as many as 54 per cent of Ukrainians do not see any existing political party they would trust to govern. Furthermore, 47 per cent of citizens would like to see the emergence of a new political force rooted in the military, while 24 per cent would welcome one drawn from volunteer groups.[10]

However, newly formed political groups would need to find leaders who are both recognisable and trusted. This stems from Ukraine’s political culture, which is marked by a high degree of personalisation: Zelensky is that kind of leader in SN, Poroshenko in ES, and Tymoshenko in Batkivshchyna. General Valerii Zaluzhnyi, former Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, who currently enjoys the highest level of public trust at 76 per cent, reflects public demand for a leader of a prospective ‘military party’.[11] If he opted to run in the presidential election, he would face the task of forming a political grouping, most likely composed, at least in part, of veterans and serving military personnel. In an effort to neutralise this potential challenger, the president’s camp is reportedly seeking to persuade him not to run and instead join Zelensky’s party as the lead candidate on its electoral list.[12] Although it remains unclear whether Zaluzhnyi intends to enter politics in any form (he has consistently stated in interviews that wartime is not the moment for such discussions), his return to the top of voter preference rankings appears likely once the ‘Trump effect’ benefiting the president fades.[13] Such a development would increase pressure from the public, military circles and parts of the business elite, including some oligarchic interests, for the general to seek the presidency.[14]

In addition to courting Zaluzhnyi, parties are also seeking to win over the broader military community. Poroshenko is publicly highlighting the scale of support he has provided to the armed forces since the start of the war, totalling 6.8 billion hryvnias (approximately 164 million dollars);[15] SN’s regional branches have taken similar steps.[16] Tymoshenko, for her part, has emphasised her role in securing better medical treatment and rehabilitation conditions for veterans.[17] When compiling electoral lists, parties are likely to compete far more aggressively than in 2015 to attract popular military figures, including high-profile commanders associated with the Azov movement, such as Andriy Biletsky and Bohdan Krotevych.[18] Officially, both have distanced themselves from politics, stressing that their active service on the front line precludes their political engagement.[19] Moreover, their individual political prospects could be hindered by the fact that they are more widely distrusted than trusted.[20]

The Justice Platform, founded in the summer of 2024 by the well-known journalist and social activist Serhiy Prytula, is seeking to meet part of the public demand for a ‘volunteers’ party’.[21] Its electoral lists could include some deputies from Holos, helping it attract the liberal electorate that has been left politically unrepresented.

Rebranding Servant of the People

The president’s party is aware of both its internal challenges and broader public sentiment. Although Zelensky himself continues to enjoy high levels of public trust (69 per cent in March 2025[22]) and leads presidential polls,[23] the same cannot be said of his party. 61 per cent of Ukrainians hold a negative view of SN, a rating even worse than that of the Platform for Life and Peace, which is associated with pro-Russian politicians.[24] SN’s difficulties will likely force it to contest the elections under a new political banner. Few active politicians would likely remain in the revamped party, whose electoral lists would feature a significant number of military figures and volunteers.[25]

At present, there are no clear signs that the president and his inner circle are preparing for elections in any practical sense. However, Zelensky is clearly working to maintain public approval; his control over both Parliament and the government enables him to take decisions aimed at wooing voters. These include initiatives such as the ‘Zelensky thousand’, a payment of 1,000 hryvnias (approximately 24 dollars) for every citizen to spend on utilities, medicine, or military bonds, as well as a moratorium on household gas price increases, extended until the end of April 2025, and a reduction in medicine prices.[26] The president has also blocked or delayed the implementation of unpopular measures, such as higher excise duties on cigarettes, which he signed into law only five months after Parliament passed the relevant legislation. In recent months, the government has also softened its approach to refugees and emigrants: for example, it has allowed men to update their military registration documents without having to return to the country.[27] By opting not to lower the mobilisation age to under 25 (until 2024, the threshold was 27), the president’s camp is also working to retain support among younger voters, a group that played a major role in Zelensky’s 2019 election victory.

If no new military-linked party emerges, the reformed SN, closely identified with Zelensky, could prove to be a strong contender simply due to the absence of convincing alternatives. The leaders of other parties face high negative ratings: 83 per cent of respondents do not trust Tymoshenko or Boyko, while 76 per cent feel the same about Poroshenko.[28] This gives the current president an edge in any potential election, as only 28 per cent of respondents express distrust towards him. If this advantage holds, the government may be inclined to hold the presidential election simultaneously with the parliamentary vote (and likely local elections as well), in order to ensure that support for Zelensky translates into electoral gains for the rebranded party.

Poroshenko as Zelensky’s main political adversary

The president’s camp is continuing its efforts to marginalise Poroshenko. He has been accused of doing business and paying taxes in Russia,[29] while his son has been fined and had his bank account frozen over alleged failure to comply with military service obligations.[30] Last February, the government imposed sanctions on the former president, freezing his assets and banning him from transferring capital abroad.[31] In March, it was revealed that the security services had opened an investigation against him on suspicion of ‘state treason’, relating to his role as foreign minister back in 2010, when he was allegedly involved in negotiating the Kharkiv Pact with Russia, an agreement considered detrimental to Ukraine’s interests. In reality, those negotiations were conducted by Viktor Yanukovych’s administration; Poroshenko had left the ministry before the agreement was signed. The scale of attacks on ES’s leader stands in stark contrast to his actual political influence and popularity. These actions should be seen as a reflection of the current president’s personal animosity towards his predecessor, and a response to Poroshenko’s criticism, including accusations that Zelensky is steering the country towards dictatorship.[32]

Despite pressure from the government, ES remains the main opposition force and a party that is coherent both internally and ideologically. Thanks to funding from Poroshenko, whose son’s wealth is estimated at over $1 billion, ES benefits from stable financing and continued access to media outlets such as Channel 5 and Espreso TV. It is also the only political formation with a net positive approval rating (34 per cent favourable views vs. 33 per cent unfavourable).[33]

ES has employed patriotic, anti-Russian, and pro-Western rhetoric, which sometimes takes on a nationalist tone. Its authenticity in this regard is reinforced by figures such as Volodymyr Viatrovych, the former head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, known for promoting the myth of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. The party has placed particular emphasis on the far-reaching Ukrainisation of public life. For instance, it firmly supported the law banning the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP). It has also called for former OPZZh deputies to be stripped of their right to participate in sessions of the Verkhovna Rada.[34]

Who will the vata vote for?

Zelensky won the 2019 election partly by attracting a segment of the post-Soviet electorate which had previously voted for the Party of Regions and is sometimes referred to as vatniks or vata. Today, this group accounts for an estimated 5 to 15 per cent of the population.[35] These people often express nostalgia for the Soviet era and speak Russian, though this does not necessarily imply pro-Russian political views. This group should not be associated solely with voters from the country’s south and east, as approximately five million internally displaced persons from those regions,[36] have since resettled in other parts of Ukraine.

They primarily support the now-banned OPZZh, which has already commenced efforts to mobilise them. Yuriy Boyko has become more active on social media, particularly TikTok, posting content in Russian that calls for protecting the Russian language and Soviet heritage. He has described the government as radicals intent on ‘destroying the mother tongue’ and ‘banning church attendance.’ He has also highlighted the challenges faced by internally displaced persons,[37]addressing the questions of identity and social welfare.

This ‘OPZZh 2.0’ may face competition within this electoral segment. In addition to SN, which includes a Russian-speaking wing, Dmytro Razumkov is also likely to woo this electorate. Some of his deputies, like Boyko, opposed banning the UOC-MP.[38]

Another key group that could determine the outcome of the election, and to which Zelensky owes much of his past success, consists of voters with little day-to-day interest in politics. They are not attached to any particular party or ideology, tend to support the candidates perceived as most likely to win and are easily influenced by negative messaging about others. Historically, this has been the largest segment of the electorate,[39] although its size is difficult to gauge during wartime. All candidates are expected to compete for its support; how this group votes will largely depend on the public’s assessment of the ceasefire terms and the scale of the economic crisis.

The electorate of anti-Western resentment

It is difficult to estimate the size of the voter group that feels ‘betrayed’ by the West, particularly the United States, believing that Ukraine’s Western partners have failed to support it sufficiently during the war, prevented it from defeating Russia, and hindered its recovery of all the lost territories. These resentments are likely to translate into calls for increasing national self-reliance, including higher defence spending, and could deepen scepticism towards the country’s integration with the EU. If the ceasefire terms turn out to be unfavourable, anti-Western sentiment may spread among large segments of the pro-Soviet, opportunistic, and fiercely patriotic electorate. This would force other candidates and parties, including Zelensky, to adopt elements of this rhetoric. In fact, Zelensky’s own criticism of the West’s slow progress in supporting Ukraine, even if partially justified, has already laid the groundwork for such positioning.

At present, Batkivshchyna appears to be engaging most intensively with this segment of the electorate. The party became more active in the second half of 2024, with Tymoshenko maintaining a visible presence on YouTube for some time. Its politicians have largely focused on criticising the government, often employing populist slogans. For instance, in the autumn of 2024, Tymoshenko claimed that medicine prices in Ukraine were higher than in Western Europe and campaigned to lower them. Most significantly, the former prime minister has adopted a strong sovereigntist tone. She has objected to the participation of international experts in selecting judges for the Constitutional Court of Ukraine and criticised a draft law which, she alleged, would allow foreign ownership of mineral resources – even before the government began negotiations with the United States on this matter. Tymoshenko has also adopted conservative positions on a range of issues, opposing proposals to decriminalise prostitution and legalise medical marijuana, a stance that resonates with her core electorate: lower-income voters from smaller towns. The biggest challenge to her party in appealing to this voter group is likely to come from Dmytro Razumkov. The former Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada has sharply criticised Zelensky in his speeches, drawing on populist rhetoric and focusing on the concerns of workers and entrepreneurs who, in his narrative, are being persecuted by the government.[40]

At the starting blocks

Donald Trump’s electoral victory has sharpened political competition in Ukraine. Despite his promises to end the war swiftly and his clear suggestions that Ukraine should hold elections, a ceasefire remains under negotiation and still appears a distant prospect. Ukrainian politicians are now seeking to remind voters of their presence, particularly given that in any future election the president’s camp will enjoy a significant advantage due to its control over administrative resources, financial means, and media infrastructure.

Since the 2019 elections, the old east-west divide in Ukraine, between a pro-European west and a pro-Russian east, has faded into the background and distinctions between parties have become increasingly blurred. The real political battle lines will not emerge until the terms of a ceasefire are announced and it becomes clear whether the public views them as a victory or defeat. This will become the key criterion by which Zelensky is judged – and by which his potential successor is chosen. The election will largely serve as a referendum on the current president and his party. Deeper social divisions, created during the war but overshadowed by ongoing fighting, are likely to resurface during the election campaign. The heightened political struggle is certain to have negative consequences for domestic stability.

[1] See T. Iwański (ed.), Defence and determination. Ukraine during the third year of the Russian invasion, OSW, Warsaw 2024, pp. 40–41.

[2] ‘Динаміка довіри Президенту В. Зеленському в 2019-2025 роках та ставлення до проведення виборів’, The Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, 27 March 2025, kiis.com.ua.

[3] M. Jędrysiak, ‘Trump–Zelensky: an escalation of rhetoric’, OSW, 20 February 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[4] K. Nieczypor, ‘Ukraina w pułapce wewnętrznego konfliktu politycznego w USA’, OSW, 2 October 2019, osw.waw.pl.

[5] J. Dettmer, ‘Top Trump allies hold secret talks with Zelenskyy’s Ukrainian opponents’, Politico, 6 March 2025, poitico.eu.

[6] Р. Романюк, ‘Опозиція справжня й удавана. Хто може врятувати "монобільшість"’, Українська правда, 18 April 2024, pravda.com.ua. It consists of two parties: the Platform for Life and Peace, led by Yuriy Boyko, and Restoration of Ukraine, whose deputies are linked to the property developer Vadym Stolar and the businessman Maksym Yefimov.

[7] J. Ber, ‘Ukraine: crisis inside the parliament’s pro-presidential camp’, OSW, 27 March 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[8] The label “Reasonable Politics” is a pun based on Razumkov’s surname, as the Ukrainian word “Rozumna” translates as “Reasonable”.

[9] K. Nieczypor, ‘Cluster, open up! Ukraine’s opportunities and risks on the road to the EU’, OSW Commentary, no. 656, 10 April 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[10] ‘Оцінка ситуації в країні та діяльності влади, довіра до соціальних інститутів, політиків, посадовців та громадських діячів, віра в перемогу (вересень 2024р.)’, Разумков Центр, 15 October 2024, razumkov.org.ua.

[11] ‘Ставлення до окремих європейських лідерів’, Соціологічна група Рейтинг, 21 February 2025, ratinggroup.ua.

[12] К. Лисенко, ‘Єрмак пропонував Залужному очолити партію Зеленського на парламентських виборах, – ЗМІ’, Політарена, 13 January 2025, politaarena.ua.

[13] K. Sienicki, T. Iwański, ‘The Trump effect: anti-American sentiment rises in Ukraine’, OSW, 24 April 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[14] І. Нестерова, ‘На тлі чуток про вибори Залужний відповів, чи збирається у президенти’, Уніан, 31 March 2025, unian.ua.

[15] П. Шевченко, О. Некращук, М. Ївженко, ‘Найбільші донатори України. Скільки бізнес виділив на гуманітарні потреби та допомогу ЗСУ — рейтинг NV’, New Voice, 11 April 2025, biz.nv.ua.

[16] ‘Підсилюємо військових на передовій’, Слуга народу, 17 February 2025, sluga-narodu.com.

[17] ‘Валерій Дубіль: Держава відшкодує лікарням витрати на покращене харчування військових’, Батьківщина, 14 January 2025, ba.org.ua.

[18] The Azov Battalion was formed in 2014 as a volunteer military unit, initially characterised by a strong nationalist orientation; some observers have claimed that it displayed neo-Nazi elements. For example, see Z. Parafianowicz, ‘Azow to realny problem. Neonazistowski pułk opłaca ukraińskie wojsko, policję i ministerstwa’, Gazeta Prawna, 15 November 2019, gazetaprawna.pl.

[19] Ю. Зіненко, ‘"У політику не йду". Кротевич прокоментував своє звільнення з посади начштабу "Азову"’, Гордон, 26 February 2025, gordonua.com.

[20] Суспільно-політичні настрої українців, SunFlower Sociology, December 2024, activegroup.com.ua, p. 8.

[21] В. Ульяненко, ‘Притула обзавівся новою партією’, Главком, 23 May 2024, glavcom.ua.

[22] ‘Динаміка довіри Президенту В. Зеленському в 2019-2025 роках та ставлення до проведення виборів’, op. cit.

[23] See the National Sample S.R.O. by NMS Market Research, a poll by the Institute of Social and Political Psychology of the National Academy of Educational Sciences from last March and a poll by Gradus from last February.

[24] ‘Оцінка діяльності фракцій у парламенті, кого вважають лідером опозиції, можливі санкції проти П. Порошенка і позбавлення мандатів депутатів від ОПЗЖ’, The Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, 13 February 2025, kiis.com.ua.

[25] М. Лєліч, У. Безпалько, ‘Вибори, Трамп і перемир'я. Чого бояться і до чого готуються у владі та опозиції’, РБК-Україна, 31 March 2025, rbc.ua.

[26] A. Крищук, ‘Нові тарифи на газ із 1 травня: які зміни очікують українських споживачів’, UA portal, news.uaportal.com, 14 April 2025.

[27] ‘Українці за кордоном зможуть стати на військовий облік без ТЦК і ВЛК – Верещук’, Укрінформ, 18 March 2025, ukrinform.ua.

[28] ‘Оцінка ситуації в країні, довіра до соціальних інститутів, політиків, посадовців та громадських діячів, ставлення до виборів під час війни, віра в перемогу (лютий–березень 2025р.)‘, Разумков Центр, 24 March 2025, razumkov.org.ua.

[29] Ю. Луканов, ‘«Закон і бізнес» витягнув знову «зраду» від Порошенка’, Цензор.НЕТ, 22 January 2025, censor.net.

[30] O. Черниш, ‘ТЦК і син Порошенка. Розповідаємо деталі скандалу і чому експрезидента можуть не пустити в Раду’, ВВС News Україна, 30 January 2025, bbc.com/ukrainian.

[31] S. Matuszak, K. Nieczypor, ‘Sanctions against Poroshenko: the start of Ukraine’s election campaign?’, OSW, 14 February 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[32] P. Ronzheimer, G. Moutafis, ‘Selenskyj bewegt Ukraine „in Richtung Diktatur“‘, Bild, 18 March 2025, bild.de.

[33] M. Jędrysiak, ‘Zelensky, Yermak and Ukraine’s wartime governance’, OSW Commentary, no. 619, 14 August 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[34] ‘ Депутати заборонених партій мають понести політичну відповідальність за свої дії – заява «Європейської Солідарності»’, Європейська Солідарність, 19 January 2025, eurosolidarity.org.

[35] Л. Ржеутська, ‘Суперечливі заяви Юрія Бойка: гра за Росію на полях TikTok?’, Deutsche Welle, 20 December 2024, dw.com; М. Лєліч, У. Безпалько, ‘У забороненій ОПЗЖ думають над створенням нової партії: що кажуть у Бойка’, РБК-Україна, 4 July 2024, rbc.ua.

[36] Г. Ялівець, ‘В Україні офіційно зареєстровано майже 5 мільйонів переселенців, – Шуляк’, Бізнес Цензор, 18 March 2025, censor.net.

[37] @boykoyurij/video/7446707036911455493, TikTok, 10 December 2024, tiktok.com

[38] С. Кошкіна, А. Стешенко, ‘«Слуги» і МП. Як заборона російської церкви поділила фракцію президента’, LB.ua, 23 August 2024.

[39] Д. Сінченко, ‘Патріоти України, колаборанти і третя група виборців. Оцінка останніх’, Радіо Свобода, 20 January 2020, radiosvoboda.ua.

[40] On his Telegram channel, Razumkov even referred to a ‘genocide’ of entrepreneurs – see ‘Дмитро Разумков_Офіційно’, Telegram, 19 March 2025, t.me.