The undeclared war. A new phase of the Azerbaijani-Armenian conflict

More than two years after the end of the Second Karabakh War in November 2020, the situation in the conflict area remains highly unstable. Despite declarations of a de facto solution to the problem, intensive peace talks and Armenia signalling significant concessions on the Nagorno-Karabakh issue, the region is once again becoming a flashpoint, as manifested by Azerbaijan’s blockade of it since December. In the process, the conflict has escalated to an open dispute between the two states. Azerbaijan has been provoking Armenia with military attacks along the line of the non-delimited state border (along which there was fierce fighting last September), and suggesting it might forcibly take over transportation routes (the so-called Zangezur corridor) on its neighbour’s territory.

These dangerous changes result from certain fundamental regional re-evaluations, which have rapidly arisen over recent years: the steady growth of Azerbaijan’s potential and the simultaneous ongoing marginalisation of Armenia; the erosion of Russia’s position and the order it previously guaranteed; and finally the growing importance and ambitions of Turkey. Considering the current local and international dynamics (primarily related to the ongoing war in Ukraine), a peaceful resolution of the conflict seems highly unlikely, and the risk of a renewed escalation of tensions between Baku and Yerevan remains high, despite the establishment of the EU’s Monitoring Mission to Armenia (EUMA) in January 2023.

Negotiations and escalations

The current stage of the crisis began with the end of the Second Karabakh War (27 September – 10 November 2020), which changed the status quo that had persisted for more than a quarter of a century. Azerbaijan regained most of the territories previously controlled by the ethnic Armenians,[1] and Russian peacekeepers were sent to the conflict zone. The truce agreement stipulated the unblocking of transportation routes, including the road linking Azerbaijan with the Nakhichevan exclave and running through Armenia; this road was intended to guarantee safe passage by Armenia, and Russian border guards were to supervise traffic along it. The agreement also mentioned the Lachin corridor, which links Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh (i.e. that part of it which remained under Armenian control). In this case, the safety of the road traffic was guaranteed by Azerbaijan, and the road was placed under the supervision of Russian peacekeepers as part of the truce. The contingent was to be stationed there for a five-year period, which could be extended for further five-year periods if neither side objected. The document did not specify what would happen after the contingent withdrew; nor did it mention what Nagorno-Karabakh’s formal status would be.[2]

From Baku’s point of view, the war had de facto resolved the conflict: domestically, the government began efforts to integrate Nagorno-Karabakh with the rest of the country in such a way as to erase its separateness (as they saw the situation, maintaining its special status was no longer an option)[3], while on the international stage they demanded an end to the use of the very name ‘Nagorno-Karabakh’. This narrative has even been given credence by Yerevan: the Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has suggested several times that he recognises Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity, and in a policy speech to parliament on 13 April 2022 he stated that the main objective of the negotiations for Armenia is no longer the status of the enclave within Azerbaijan, but security guarantees for the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh[4] (the discussion of their fate in the longer term has apparently been suspended). Thus, the focus of the conflict has shifted to relations between the two states (although this dimension already existed: Yerevan represented Stepanakert in the talks, and also maintained a military presence in Nagorno-Karabakh). The main subject of dispute is now the formula for normalising relations between the two countries, which (like Armenia and Turkey) do not have diplomatic relations. The issues at stake include delimiting their common border and how to implement the arrangements which ended the war. According to Baku, the November 2020 agreement should give it the ability to implement strategic communication projects on Armenia’s sovereign territory.

Russia took a long time to get involved in the Second Karabakh War (this could be explained by the fact that hostilities were taking place on what was de jure Azerbaijani territory), but when the fate of Stepanakert (Azerbaijani Khankendi/Xankəndi) was at stake, the Kremlin forced the parties to reach a ceasefire. For this reason, Moscow’s position as a mediator seemed secure. Throughout almost the whole of 2021, negotiations took place under its supervision[5] – among other things, two meetings between the leaders of the three countries were held at which it was agreed to take steps toward Azerbaijani-Armenian normalisation. However, it turned out that these commitments are not being fulfilled, and Russia does not have enough will and/or strength to enforce them. At the same time Baku (with support from Ankara) ‘tested’ Moscow’s reactions by periodically escalating tensions in the region: armed incidents took place in May, July and November 2021 (on some occasions Azerbaijani soldiers crossed the border with Armenia in places that Baku disputes)[6], which did not meet with any interventions by the Russian peacekeepers.

As recently as 22 February 2022 Vladimir Putin and Ilham Aliyev, the presidents of Russia and Azerbaijan, signed a Declaration of Allied Cooperation in which they mutually recognised the territorial integrity of their countries (and, implicitly, the membership of Crimea in the Russian Federation). This may have indicated Baku’s support for the Kremlin’s actions, but in practice it was a forced concession to Moscow (Baku had previously proclaimed that it supports the territorial integrity of Ukraine). However just a month later, on 24 March, Azerbaijan seized a village in the Russian peacekeepers’ zone, and sharply dismissed the official Russian communiqué downplaying the incident.[7] Thereafter Brussels began to assume the role of intermediary. The first meeting in the new format (Aliyev, Pashinyan and the European Council’s President Charles Michel) was held on 14 December 2021, and subsequent meetings took place in April, May and August 2022. The intense peace talks were accompanied by increasingly violent military escalations. The most serious occurred on 12–14 September, when 105 Armenian and 71 Azerbaijani soldiers were killed, and Azerbaijani forces allegedly occupied 10 km2 of Armenian territory. These events confirmed that a real state of war now existed between the two states.

While doing so, though, both Baku and Yerevan declared (and continue to declare) that they are open to a peace agreement. However, the parties cannot agree on the sequence of steps that should be taken (due to their total lack of trust, neither of them wants to be the first to make any such move), nor on what route the road from Azerbaijan to the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic should run, or what traffic rules should apply on it (this issue is a priority for Baku). In addition, Armenia wants credible security guarantees, as it fears that without them its neighbour will use its advantage to make further demands (on 15 February this year Yerevan presented a new peace proposal to Baku). In this situation, Azerbaijan is trying to ‘coerce Armenia into peace’, an approach which actually threatens to escalate the hostilities further.

Azerbaijan attacks...

Although more than two years have now passed since the Second Karabakh War, not only has the road to Nakhichevan not been opened, there has not even been any agreement upon its route, and much of Nagorno-Karabakh remains outside Azerbaijani control. Without giving up on diplomatic efforts, Baku is increasingly resorting to threats of force, while the periodic escalations of tension are meant to demonstrate its resolve. The addressees of this policy are as much Moscow and the Western capitals as Yerevan. Azerbaijan is resisting any initiatives, which it believes would preserve the current state of limbo, such as the EU’s October 2022 deployment of an observation mission to the border between it and Armenia, and the January 2023 decision to set up a two-year EU mission in Armenia (the European Union Mission in Armenia, EUMA). As it seems, in the calculation of the government in Baku, an important role is played by the awareness not only of the potential they possess (which is bolstered by its alliance with Turkey)[8], but also of the favourable international situation. First and foremost is the effective self-restraint being practiced by Russia, busy with its involvement in Ukraine: the escalation last September, when the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) failed to respond to Azerbaijani attacks on targets in Armenia,[9] coincided with the successes of the Ukrainian counter-offensives in the Kherson and Kharkiv areas. Another important factor is the EU’s growing interest in energy cooperation (such as the EU-Azerbaijan memorandum on increasing gas supplies in July, and the strategic partnership agreement in December 2022 on the development and transportation of green energy)[10].

In recent months, Baku has opted for a hybrid series of moves. One such is the blockade of the route through the Lachin corridor linking the Karabakh Armenians to the outside world (the parastate is supplied with food, medicine, cleaning supplies etc. via this route), which began on 12 December 2022. Although this venture is being spearheaded by alleged environmental activists demanding permission to monitor Karabakh’s rare metal deposits (which have been targeted for exploitation), it would be impossible to carry out such an action in Azerbaijan without the cooperation of the authorities.[11] The Karabakh Armenian side is talking in terms of a major humanitarian crisis; it has also been suggested that the operation is intended to induce all the ethnic Armenians to leave the enclave. Politically, the most likely goal of the blockade is to force Yerevan to agree to open the road to Nakhichevan on Baku’s terms. Azerbaijan wants it to run along Armenia’s border with Iran and to function as an extraterritorial corridor (the so-called Zangezur corridor), wherein the transit traffic will not be subject to Armenian control. Yerevan proposes a different route (as it fears that the region will otherwise be cut off from Iran), and refuses to accept any form of extraterritoriality. On 10 January 2023, Azerbaijan’s President Aliyev said that the ‘corridor’ will be activated “whether Armenia wants it or not”, which can be interpreted as a declaration to push through its creation by force.[12] It is even possible that Azerbaijani forces will temporarily occupy part of Armenia’s territory and construct the road infrastructure there (a policy of fait accompli), but the presence of EU observers would raise the political cost of taking such a step. For this reason, the prolonged occupation of the south of the country, which would become a land ‘bridge’ to Nakhichevan and Turkey, currently seems unlikely – although the authorities in Baku are making territorial claims of Yerevan.[13]

Azerbaijan’s long-range goals are the delimitation of the border with Armenia, taking into account its preferences regarding its route, and the development of the regional communications infrastructure. Achieving these aims would, on the one hand, allow Azerbaijan to reduce its dependence on transit through Georgia, and on the other, to gain control of transit through Armenia, which would ultimately consolidate Azerbaijani-Turkish dominance in the region while marginalising both Georgia and Armenia.

...while Armenia is playing deep defence

Despite his country’s defeat in the war, Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has remained in power and succeeded in renewing his mandate (his party won the parliamentary elections held on 20 June 2021). Yerevan had hoped for a quick peace deal that would ensure the preservation of the status quo established after the Second Karabakh War, guarantee the security of the Karabakh Armenians and the protection of the Armenian cultural heritage there. He did not agree to Baku’s demands on the route and status of the road linking Azerbaijan’s core territory with Nakhichevan, and so he adopted the tactic of playing the ‘waiting game’. This involves a policy of reaction, while maintaining correct relations with all the relevant players and waiting for a better turn of events. Behind this decision is not only the awareness of his own weakness and his minimal influence on the course of the peace process, which results in a lack of leverage and – in the extreme scenario – threatens a loss of sovereignty over part of his country’s own territory, but also the lack of any strategic idea for Armenia’s place in the region and its relations with its neighbours, as demonstrated by his inconsistent statements and his frequent replacements of foreign minister.

Yerevan’s position is further weakened by its declining influence in Nagorno-Karabakh, which is led by a group opposed to Pashinyan, and has links to the former Armenian presidents Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan. Armenia has withdrawn its regular military units from the parastate, while its recognition of Azerbaijan’s integrity is perceived by the Karabakh Armenians as a betrayal. In Armenia itself, the issue of ‘saying goodbye’ to Nagorno-Karabakh is a cause of deep trauma – regardless of the realisation that, under existing realities, Baku’s takeover of the entire area appears to be only a matter of time. This may result in social and political upheaval in the future. In this situation, Moscow has taken the place of the parastate’s ‘patron’. In all likelihood, it can be assumed that Ruben Vardanyan – a Russian oligarch of Armenian descent, who moved there from Moscow in late 2022 and took over as head of the Karabakh government – is a ‘Russian project’. While he was dismissed on 23 February (most likely as a result of pressure from Baku), he has nevertheless declared that he will remain in the region. It is possible that there is a (Russian) scenario according to which Vardanyan would – with the support of the so-called Karabakh clan, and taking advantage of the public frustration – someday replace Pashinyan, who is notably unsympathetic to the Kremlin.

Yerevan seems incapable of resolving the strategic impasse, and finds itself in effective isolation. It shares a strategic partnership with Moscow, but the latter is not living up to its commitments. The support Paris provides is almost exclusively political and has drawn protests from Baku, which accuses France of bias.[14] The gestures from Washington – including a visit by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi on 17–18 September last year – were not followed by concrete assistance (nor did Armenia make a more explicit effort to obtain any). There is more potential in the above-mentioned EU missions which, regardless of Azerbaijan’s signalled reluctance, are easing tensions in the region. The ongoing talks with Turkey on normalising relations (in December 2021 the parties appointed special representatives for this purpose) are being sabotaged by Baku. Ankara in turn has made this conditional on the early signing of an Armenian-Azerbaijani agreement.[15] In a situation of struggle for survival, Iran remains no more than a hypothetical alternative, even though it has consistently offered Armenia both military and political support (including opening a consulate in Kapan, in the south of Armenia, in response to the September clashes). However, Tehran’s potential is insufficient to achieve anything of substance; nor is there any consensus within Armenia itself for closer cooperation with it over the categorical objections which Washington would make.

A new Caucasian ‘concert of powers’

The dynamics of the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan are closely embedded in the region’s political processes: it is both an expression and the co-creator of them. The primary issue is the progressive erosion of the post-Soviet order, based on Russia’s dominance in the sphere – at the very least – of security. Armenia used to serve as one of the most important instruments of this hegemony; among other things, it guaranteed the Russian military presence in the Caucasus and acted as a deterrent against Azerbaijan and Turkey. The 2020 war already demonstrated the anachronism of this model, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine has deepened the process of revising it. Another important factor in this process is Turkey, whose capabilities in the Caucasus were also confirmed during the Second Karabakh War. Moscow’s loss of status and Ankara’s rise to prominence are directly affecting the potential and capacity of both Baku and Yerevan, as well as the dynamics of the processes throughout the region.[16]

The key regional relationship between Russia and Turkey is based on ‘strategic ambivalence’ in terms of security and economic policy; the Caucasus is just one of several theatres where this approach is being played out. On the one hand, it means fierce rivalry and (in the recent past) teetering on the edge of armed clashes (including several occasions during the conflict in Syria). On the other, both countries are well aware of the risks, interdependencies and benefits of mutual cooperation. This leads them to a long, slow search for a compromise model of relations. Ankara’s main goals remain the consolidation of its influence in Azerbaijan and the development of a communications infrastructure with Azerbaijan, and on to Central Asia (the so-called Zangezur corridor would allow diversification); also, by boosting its regional position, it wants to strengthen its room for manoeuvre in its relations with Russia, the West, China and Iran.

For Moscow, which no longer sees Yerevan as an effective partner or instrument, the solution seems to be to develop strong ties of interdependence with Turkey (and Azerbaijan) and to seek instruments for control and containment other than Armenia. In the region, Georgia could play such a role for Russia; the most important transportation routes run through it, and the state itself is becoming increasingly vulnerable to Russian influence (for reasons including deteriorating relations with the West, pressure from Moscow and potential fears of Turkish-Azerbaijani hegemony). Outside the region, Iran has traditionally remained an auxiliary instrument for the Kremlin. For Russia and Turkey, an objectively stronger Azerbaijan is an indispensable partner, while a weak Armenia can be an object of policy and also a possible area for compromise. Finally, the two countries share the conviction that the revision of the regional order is a risky but inevitable process, and that it should take place without the participation of other external players – including the West. Proof of this – in addition to the deepening conflict between the Kremlin and the West and continuing Turkish-Western tensions – includes their shared aversion to any negotiating formats headed by the OSCE Minsk Group. In the perspectives of both Ankara and Moscow, the Caucasus is still among the most important theatres for the development of a model of complex bilateral relations.

Prospects

Relations between Azerbaijan and Armenia (and the Karabakh Armenians) are and will remain strained for the foreseeable future. The chances of a peace agreement (or even a breakthrough in the peace process) are slim, although such a development cannot be ruled out entirely. The parties are characterised by their extremely limited mutual trust. For Armenia, the fundamental issue is their lack of credible negotiating mechanisms, and – above all – of any guarantees that the agreements they reach will be implemented. Neither Russia (whose credibility has radically declined), nor Turkey (a de facto party to the conflict), nor the West (which has only limited instruments in the region and also lacks the political will) can provide them. For Azerbaijan, on the other hand, with its ever-growing ambitions and the deepening power imbalance between it and its opponent, a final agreement ending the conflict would, paradoxically, tie its hands.

If the current state of affairs continues, this will mean a constant high risk of further incidents, both around Nagorno-Karabakh (putting pressure on Armenia and the Karabakh Armenians) and on the border between Azerbaijan and Armenia. In an extreme scenario, Azerbaijan could attempt to seize the so-called Zangezur corridor by force, which would put Armenia’s territorial integrity and sovereignty at stake. Such continued tensions (for example, around Nagorno-Karabakh), let alone any effective military intervention, would continually undermine the position of the government in Yerevan. The danger of clashes between the two countries has been significantly reduced – although not abolished – by the EU’s EUMA monitoring mission.

The region is also being significantly affected by the wider international situation, which also minimises the chances for peace. The dynamics of the war in Ukraine and its difficult-to-predict effects on Russia’s position have motivated Ankara and Baku to keep testing Moscow, but they also make any binding settlement premature. Also uncertain is the situation in Turkey, which not only has to contend with its own complex relations with the West and Russia, but also faces the prospect of presidential and parliamentary elections (14 May this year), which will be held amid acute internal tensions heightened by the catastrophic earthquake of 6 February. An additional element of uncertainty comes from Iran (which saw unprecedented protests and harsh repression in the autumn of 2022, as well as regular acts of sabotage, such as in January this year), which will directly or indirectly involve all the players in the South Caucasus and the Middle East.

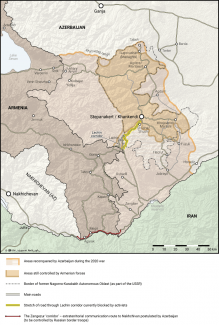

Map. The Nagorno-Karabakh region and the southern section of the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan

Source: authors’ research.

[1] After the end of the First Karabakh War (1992–4), Armenian forces controlled approximately 14% of Azerbaijani territory. This area consisted of almost all of the former Soviet Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) and the ‘occupied territories’ bordering the NKAO to the west, south and east. After the Second Karabakh War, Azerbaijan regained all of these ‘occupied territories’ (partly as a result of the fighting, and partly as a result of the agreement that ended the war) as well as about a third of the former NKAO itself (this as a result of their territorial conquest). A separatist Armenian parastate, the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, still exists on the remainder of the former NKAO.

[2] ‘Заявление Президента Азербайджанской Республики, Премьер-министра Республики Армения и Президента Российской Федерации’, the Administration of the President of Russia, 10 November 2020, kremlin.ru. It is possible that this text was written by Putin himself.

[3] On the occasion of the redivision of the country into economic districts, the former NKAO (i.e. both the areas controlled by Baku and those where ethnic Armenians are de facto in power) was merged with the region of Lowland Karabakh, which is not the subject of any territorial disputes. See ‘New economic regions of Azerbaijan – LIST’, Report News Agency, 7 July 2021, report.az

[4] W. Górecki, ‘Yerevan’s radical turn in its Nagorno-Karabakh policy’, OSW, 15 April 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[5] Russia held the formal mandate to do so by dint of its co-chairmanship (with France and the US) of the OSCE Minsk Group, which was set up in 1992 to moderate the Karabakh peace process. As a result of the 2020 war the Group de facto lost its relevance, but it has de jure continued to exist the whole time.

[6] These include the gold-bearing areas east of Lake Sevan (the area around the towns of Sotk and Verin Shorzha) and those through which the road linking Yerevan to the south of the country and onward to Iran runs (around the town of Goris).

[7] W. Górecki, ‘Tension escalates in Nagorno-Karabakh’, OSW, 28 March 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[8] W. Górecki, M. Chudziak, ‘The (pan-)Turkic Caucasus. The Baku-Ankara alliance and its regional importance’, OSW Commentary, no. 374, 1 February 2021, osw.waw.pl.

[9] W. Górecki, ‘Fragile truce in the Caucasus: Yerevan’s lsolation, Baku’s assertiveness’, OSW, 16 September 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[10] This was signed by Romania, Hungary and Azerbaijan, and (as a transit country) Georgia. K. Całus, A. Sadecki with W. Górecki, ‘The South Caucasus-EU green electricity bridge plan’, OSW, 27 December 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[11] W. Górecki with K. Chawryło, ‘Blockade of the Lachin corridor. Nagorno-Karabakh introduces ration coupons’, OSW, 17 January 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[12] Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by local TV channels, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, 10 January 2023, president.az

[13] On 24 December 2022 Aliyev called “western Azerbaijan”, or present-day Armenia, “our historic land”. Ilham Aliyev viewed conditions created at administrative building of Western Azerbaijan Community, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, 24 December 2022, president.az

[14] Following the talks in Prague between Aliyev and Pashinyan on 6 October 2022 on the margins of the European Political Community Summit, which the French President Emmanuel Macron attended alongside Charles Michel, the Azerbaijani leader cancelled the next meeting in the ‘Brussels’ format, which had originally been scheduled for November.

[15] At the same time, however, in January 2023 Ankara reversed its ban on cargo flights between Turkey and Armenia after a 30-year hiatus, while following the earthquake in Turkey on 6 February 2023 Yerevan sent it assistance across the Armenian-Turkish border, which is formally closed.

[16] W. Górecki, K. Strachota, ‘The Caucasus deregulated. The region on the anniversary of the end of the second Karabakh war’, OSW Commentary, no. 418, 26 November 2021, osw.waw.pl.