The EU’s security and defence policy: in search of a compass

In the EU, work is underway on the Strategic Compass, a security strategy that is intended to define the Union’s priorities in crisis management, capability development, partnerships and resilience for the next 5–10 years. It aims to define the EU’s role in an increasingly complex security environment where NATO and the US are redefining their priorities. The Strategic Compass is also intended to maintain the momentum of the EU initiatives launched in 2016, such as the Permanent Structured Cooperation or the European Defence Fund. The process of developing the document, and the EU’s security and defence policy in general, has been marred by the member states’ conflicting threat perceptions and interests. Nevertheless, under pressure from France and the European Commission, the EU has been making some progress in this area. The Strategic Compass will set the framework for Union’s future actions. However, implementing the strategy will depend on the member states’ commitment to the means and goals agreed, and thus cannot reflect the interests of one group of EU countries alone.

Looking for a common denominator

The development of the EU’s cooperation in security and defence accelerated after 2016, primarily due to the reconfiguration of the Union after the Brexit referendum and the changing transatlantic relationship after Donald Trump won the US presidential elections. At the turn of 2021, the EU’s military, industrial and financial initiatives, including the Permanent Structured Cooperation, the European Defence Fund and the European Peace Facility, were either reviewed or took their final shape. Ultimately, they are a result of a compromise between the ambitious proposals of the European Commission and the diverging priorities of the EU countries. Their budget has been set at levels well below the original expectations.

Paris has been the prime mover behind these increased ambitions. France wishes for more EU military engagement in the southern neighbourhood, as well as a consolidation of the arms industry in Europe, in support of French interests. It has also advocated European strategic autonomy, which will de facto come at the expense of NATO. Berlin favours a bigger footprint for the EU in security and defence, but still considers NATO the most important military organisation which will guarantee the collective defence of Europe. Some countries, especially on the eastern flank, have been sceptical about the development of the EU’s security and defence policy as perceived through the prism of France’s interests and far-reaching ambitions. Despite all this, the forging of a common denominator in the EU’s security and defence policy is proceeding.

The Strategic Compass, a document that is intended to define the EU’s role in security and defence in accordance with the treaties,[1] is the most recent initiative of a more strategic dimension. It was initiated by Germany, which held the Presidency of the Council of the EU in the second half of 2020. Berlin wants to maintain the security and defence momentum in the Union, but also wishes to counteract the French push to develop external military co-operation formats, such as the European Intervention Initiative, or to form ‘coalitions of the willing’ under French leadership. During the development of the Strategic Compass a non-public threat analysis was developed. At present, after consultations with the expert community, a debate on the document is being conducted among the member states. The document’s first draft will be presented by the European External Action Service in November 2021, and is expected to be agreed and adopted by March 2022, during the French Presidency of the Council of the EU. The current debate on the future of the Union’s security and defence policy, and hence the Strategic Compass, has also been affected by the widely criticised US-led withdrawal from Afghanistan.[2]

Security and defence initiatives: where are we?

Military cooperation

Military-technical cooperation between the 25 member states has been gradually developed since the end of 2017 within the 47 PESCO projects. The long-term objective is to jointly achieve a coherent full-spectrum force package for missions and operations, at a level which matches the EU’s ambitions. The PESCO projects aim to strengthen and build joint capabilities for land, maritime, air, space and cyber operations, to develop joint enablers and to support joint training (see Table 1 in the Appendix).

The 2020 PESCO Strategic Review[3] showed the results of the previous military-technical cooperation to be unsatisfactory. Only 26 of the projects will deliver concrete results or reach full operational capability before the end of 2025. Only a few of the participating member states consider multinational cooperation in capability development to be an important objective; the majority prefers national approaches. National armament programmes consume the lion’s share of their modernisation budgets, leaving little room for cooperation projects within the EU.[4]

Progress in meeting the PESCO commitments is judged to be far from sufficient. A new set of commitments, incentives and guidelines for the next five years was therefore adopted in November 2020. The PESCO projects are to be modified, merged, or closed if they do not deliver the expected results; one has already been terminated because it was duplicating the work of others. The developments in Permanent Structured Cooperation are to be discussed more often at a higher political level in order to motivate the participating member states; the PESCO secretariat is to be given a greater supportive role in developing collaboration. The projects should also be better coordinated with other financial and industrial instruments such as the European Defence Fund.

Industrial cooperation

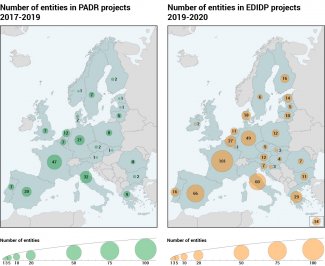

The European Defence Fund (EDF) came into force in 2021 with a budget of almost €8 billion for the next seven years (2021–2027); in May 2021, the first calls for proposals were announced.[5] The Fund is intended to increase the competitiveness of the European arms industry and support the development of capabilities necessary for the conduct of EU’s military missions and operations. As the EDF was launched, two test instruments that prepared the EDF’s implementation (PADR and EDIDP) were terminated. It is difficult to estimate to what extent their effects (and, in the future, that of the EDF) will contribute to the modernisation of the member states’ armed forces. However, it is possible to see which entities have been able to increase their competitiveness thanks to the EU funding (see Map 1 in the Appendix).

The Preparatory Action on Defence Research (PADR), with a budget of €90 million for 2017–2019, co-funded a total of 18 multinational projects focused on research & development of defence products and technologies.[6]Entities from France (47) and Italy (32) won most of the grants, followed by Germany (21) and Spain (20). The PADR projects involved both large arms companies (Italy’s Leonardo; France’s Thales, Safran and MBDA; Germany’s MBDA; Spain’s Indra and Sweden’s SAAB), which received the largest grants of several million euros, and small- & medium-sized companies and research institutions. In Central and Eastern Europe, entities from Poland (8) and Lithuania (5) were involved in the largest number of projects.

The European Defence Industrial Development Programme (EDIDP), for its part, aimed to support the development of defence technology prototypes. With a budget of €500 million for 2019–2020 it co-funded 42 multinational projects, in which several hundred companies and institutions participated, most from France (101), Spain (66), Italy (60) and Germany (49).[7] More than 35% of EDIDP beneficiaries were SMEs. The remainder are R&D institutions (in the minority) and French, Spanish, Italian, German and other large arms companies or their subsidiaries. In Central and Eastern Europe, Estonia (14) and Poland (12) received the most grants.

Cooperation in crisis management

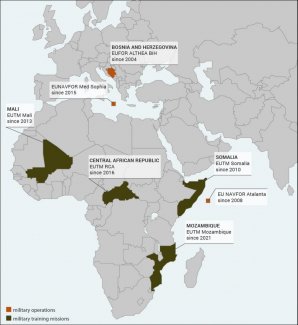

Since 2016 there has also been an ongoing debate in the EU on increasing funding for activities that help to prevent conflicts and promote peace in the European neighbourhood. In 2021 the off-budget European Peace Facility (EPF) was established with a budget of €5 billion for 2021–2027. The EPF is to take over the financing of the common costs of the EU’s military missions and operations (5–10% of their overall financing), which so far have been covered by the Athena mechanism (see Map 2 in the Appendix).

The EPF will also co-finance peace support operations led by third countries and international organisations.[8] It will gradually take over the co-financing of the African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM); the G5 Sahel Joint Force (a framework of cooperation between Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger); the ECOWAS Mission in the Gambia (ECOMIG); the Ceasefire & Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring & Verification Mechanism in South Sudan (CTSAMVM); the Multi-National Joint Task Force fighting Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin; the African Union Observer Mission (MOUACA) and the Special Joint Security Units (USMS) in the Central African Republic. Furthermore, the EPF will allow also for the financing of military activities that are not African-led (such as the French Takuba operation in the Sahel), or missions outside Africa.

The EPF is also intended to give financial support for the capacity-building of third countries and international organisations by co-financing military infrastructure and the supply of military equipment, armaments and munitions. This has been a controversial innovation among the EU’s external activities. Supporters of such assistance argue that the EUTM missions train (African) forces that often lack the arms and military equipment to put training effects into practice; its opponents claim that such deliveries may simply inflame local and regional conflicts.

The Strategic Compass: where are we heading?

In 2016 member states agreed to set out the EU’s level of ambition in security and defence on the basis of the EU Global Strategy. Three priorities were highlighted: responding to external conflicts and crises in accordance with Article 43 of the TEU,[9] capacity building of partners,[10] and protecting the EU and its citizens.[11] As this constitutes a rather broad catalogue of tasks, the Strategic Compass is intended to specify what the EU wants and can do in four areas.

Crisis management

A fundamental question is whether, how and where the EU should conduct military crisis management operations. The security environment around the EU is deteriorating and becoming more complex at the same time. Russia, Iran and Saudi Arabia, among others, are becoming directly or indirectly increasingly involved in crises and conflicts in Africa and the Middle East. Military activity in these regions has more and more in common with regular warfare. More substantial crisis management interventions in these places by the EU would often require larger political and military contributions from member states – and most of them, particularly after involvement in the interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, are not ready to do so.

The EU is currently conducting seven small-scale military missions and operations, concentrated mainly in Africa, in which a mere ~3000 soldiers are engaged (see Map 2 in the Appendix). There is a continual problem of force generation for these operations, which shows a lack of commitment on the part of the member states. Various goals with regard to crisis management set within the EU in the past have not been met. This includes the Helsinki Headline Goal 1999, which expressed the ambition to have up to 60,000 troops deployable within 60 days and sustainable for up to one year on more than one CSDP operation. The EU Battlegroups, a concept that was part of the Headline Goal 2010, have never been used operationally.

In the development of the Strategic Compass, then, proposals to increase the political readiness and military capacity of the member states to conduct operations under the EU banner are being made. In military terms, some EU states are pushing the idea of creating an initial entry force of around 5000 soldiers for rapid expeditionary deployment.[12] In the political dimension, discussions concerning the use of Article 44 of the TEU are ongoing; this states that the Council may entrust the implementation of a task to a group of member states. Activating this article could facilitate planning and conduct for military missions and operations by a ‘coalition of the willing’ within the EU. This is in the interest of Berlin, which is sceptical of coalitions under French command conducted outside of the Union (such as the Takuba Task Force in the Sahel and the EMASOH operation in the Strait of Hormuz), in which due to constitutional constraints it cannot, and often does not want to participate. Article 44 of the TEU would make it easier for France to conduct operations under the EU flag while theoretically allowing military participation and/or at least partial political oversight by Germany.

Capability development

The wish of some member states to involve the EU more in crisis management in the southern neighbourhood is also related to the issue of developing adequate military capabilities. Thus one of the discussions around the Strategic Compass is focused on what expeditionary capabilities member states should invest in, to what degree they should be jointly developed, and how they should be supported within the EU. This partly clashes with the priority of strengthening European armed forces for conducting collective defence within NATO.[13] The latter is of key importance to member states in both central & eastern Europe and also in northern Europe.

The planning of capability development in the EU, which uses various instruments, is quite complex.[14] Its results apply to the EU as a whole and not just to individual member states, as is the case in NATO. Therefore the relevant processes in the EU serve as reference points for member states to just a small extent, and they are often interpreted in accordance with the individual national interests. The EU’s Capability Development Plan (CDP), updated in 2008, 2014 and 2018, is officially one of the main tools in this field. The eleven Capability Development Priorities identified in 2018 largely overlap with NATO targets. Interestingly, the recent debate on this in the EU has focused on achieving High Impact Capability Goals (HICGS); these are capability shortfalls in key strategic areas that were identified in 2019 as part of elaborating the CDP. Apart from this, commitments to meet the Headline Goals 1999 and 2010 have theoretically also been implemented for years. Additionally, the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) introduced after 2016 is intended to provide a picture of the European defence landscape with the capability development and research & development efforts, and to propose opportunities for multinational cooperation. The 2020 CARD Report highlighted six focus areas[15] which the member states should jointly invest in. The Strategic Compass will also present guidelines for capability development in the EU.

Partnerships

Another question under discussion is how the EU should position itself in relation to organisations such as NATO, how it wants to define its geographic and thematic priorities for cooperation with partners in Europe’s neighbourhood, and how it should shape its security relationships with the US and the UK.

One of the big challenges ahead is the division of labour between the EU and NATO. Both organisations are currently in the process of developing their own security strategies: in 2022 the EU plans to approve the Strategic Compass, and NATO will decide upon its new Strategic Concept. In the future, closer political and military coordination between the two organisations will be crucial. NATO wants to become more political and the EU more military. According to the NATO 2030 Agenda, the Alliance should become a platform for extended political dialogue between the US and Europe.[16] In this dialogue the position of the EU will be key, due to its competence in trade, economic, and technological policy. On the other hand, in view of the EU’s growing military ambitions, greater coordination with NATO will be crucial.

Some voices in the debate on partnerships have called for a geographical concentration of military cooperation with countries in the southern neighbourhood, mainly Africa. This is in line with the interests of some EU member states – France, Italy and Spain – and with the EU’s recent operational engagement. At the same time, the results of the previous military cooperation have been contested. More and more attention has been drawn to the fact that military assistance to partners in the southern neighbourhood should not be provided at the expense of supporting broader institutional reforms in those countries, linked to fostering political stability and economic development.[17]

Resilience

The inclusion of resilience as one of the topics of the Strategic Compass results from the Union’s 2016 level of ambition that highlighted the protection of the EU and its citizens. This is an extremely broad area that includes strengthening the protection and resilience of critical networks and infrastructure, the security of the EU’s external borders, civil protection and disaster response, ensuring stable access to the global commons (including the high seas and space), countering hybrid threats, cybersecurity, preventing and countering terrorism and radicalisation, combatting people smuggling, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, arms trafficking and organised crime. Defining a more concrete EU agenda in this area is thus an issue, with member states pushing their own priorities.

The operational use of the mutual defence clause has been discussed in this context. Article 42.7 TEU[18] is theoretically an equivalent to NATO’s Article 5, and provides a legal basis for collective defence in the European Union. However, there is no consensus among the member states on developing the EU to a military alliance as an alternative to NATO. However, there is an ongoing debate about the non-military role the Union can play in response to armed aggression against a member state – complementary to NATO’s actions, or in response to hostile hybrid activity below the threshold of Article 5 of the Washington Treaty.

Conclusions and perspectives

The development of the EU’s security and defence policy since 2016 has gained a new dynamic. In contrast to previous attempts to strengthen the EU’s role in this area, this trend may actually continue due to several factors. The UK, which delayed this process in the past, is no longer in the EU, and the US and NATO are changing their security and defence priorities. The Strategic Compass will set the framework for the EU’s political, military and financial activities over the next 5–10 years. However, if it does not sufficiently balance the priorities of all the member states, then some of them will not be interested in its implementation. It is worth remembering that the decisions relating to security and defence policy are taken by the Council of the EU by unanimity, and this is unlikely to change any time soon. The Strategic Compass should thus adopt a 360-degree approach and take into account the needs of all member states in the crisis management, capability development, partnerships and resilience. Close alignment of the development of the EU’s Strategic Compass with the NATO’s Strategic Concept in all the areas mentioned is a must. The central and eastern European members need to actively shape the process of developing the strategy at both the administrative and political levels.

In crisis management, ambitious proposals such as the creation of an initial entry force should not obscure the lack of both political will and military capabilities in the EU countries, as well as the complex security environment that makes large-scale interventions in the European neighbourhood unlikely. The EU’s strength lies in its ability to develop a broad civil-military approach in which military operations and advisory & training missions, as well as cooperation on armaments and equipment, are embedded in a comprehensive strategy that includes support for civil administration and institutional reforms, a better coordination of different foreign instruments (humanitarian aid, development and economic cooperation, diplomacy, conflict prevention) and a division of labour with other international organisations (including NATO), individual member states, and the US.

The EU’s crisis management and partnerships in security and defence should not be exclusively southward-looking. Security challenges for the entire EU also stem from the Western Balkans and the Eastern Partnership countries.[19] The security and resilience of these countries can be improved through stronger cooperation with the EU. The EU’s relations with selected partners in the south-eastern and eastern neighbourhoods should thus include a more robust security and defence component. A decision to send an EU training mission to Ukraine, as some member states have proposed, will be a test of the EU’s 360-degree approach.[20]

Moreover, a broad approach towards capability development is necessary. The EU should not only support military and industrial cooperation projects which are relevant to crisis management, but also to collective defence. The key to coherence and reconciling the member states’ different priorities is closely aligning the EU instruments with the established NATO ones. With regard to resilience, the EU might better support member states and NATO in their non-military responses to armed or hybrid aggression through assistance in external border management, security of supplies, energy, cyber and information security and civilian crisis responses, as well to political and economic pressure from actors such as Russia and China.

APPENDIX

Table 1. on PESCO projects is available here.

Map 1. Participation in PADR and EDIDP projects

Source: author’s calculations based on EU data. See footnotes 6 and 7.

Map 2. The EU’s military missions and operations

Sources: ‘Military and civilian missions and operations’, 5 March 2019; ‘Mozambique: EU sets up a military training mission to help address the crisis in Cabo Delgado’, 12 July 2021, European External Action Service, eeas.europa.eu.

[1] The legal basis of the common security and defence policy is regulated by Articles 42–46 of the Treaty on European Union. The EU can draw on the civilian and military assets of the member states in carrying out peace-keeping missions, conflict prevention and strengthening international security. The common security and defence policy shall include “the progressive framing of a common Union policy” that can lead to a common defence in case the member states decide so unanimously. However, both the Treaty provisions and most EU countries recognise that NATO is responsible for collective defence of its members. The EU’s activities in security policy are intergovernmental in nature, with the exception of the arms industry, transport and research & development, where the European Commission plays an important role. ‘Ośrodek Informacji Dokumentacji Europejskiej, ‘WPBiO – architektura prawno-instytucjonalna’, Materiały OIDE, 2 July 2018, oide.sejm.gov.pl

[2] T. Breton, ‘Afghanistan: common European defence is no longer an option’, Linkedin, 27 August 2021, linkedin.com.

[3] ‘Defence cooperation: Council approves conclusions on the PESCO Strategic Review 2020’, Council of the European Union, 20 November 2020, consilium.europa.eu.

[4] 2020 CARD Report. Executive Summary, European Defence Agency, November 2020, eda.europa.eu.

[5] European Defence Fund (EDF) calls 2021, European Commission, 30 June 2021, ec.europa.eu.

[6] Preparatory Action on Defence Research (PADR), European Commission, ec.europa.eu.

[7] European Defence Industrial Development Programme (EDIDP), European Commission, ec.europa.eu. In addition, two PESCO projects, Eurodrone (European MALE Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems, €100 million) and ESSOR (European Secure Software-defined Radio, €37 million), were directly supported through EDIDP in 2019.

[8] The EU has co-financed the expenses of such operations, including soldiers’ transport and living costs and the construction of military infrastructure, via the off-budget African Peace Facility (APF).

[9] Article 43 of the Treaty on European Union lists: joint disarmament operations, humanitarian and rescue tasks, military advice and assistance tasks, conflict prevention and peace‑keeping tasks, tasks of combat forces in crisis management, including peace‑making and post‑conflict stabilisation. All these tasks may contribute to the fight against terrorism, including by supporting third countries in combating terrorism in their territories.

[10] Capacity building of partners covers tasks in training, advice and/or mentoring within the security sector in order to contribute to the resilience and stabilisation of partner countries recovering from or threatened by conflict or instability. It also includes countering hybrid threats (strategic communication, cyber security, border protection, observing international law, the protection of civilians, good governance).

[11] See J. Gotkowska, A European Defence Union? The EU’s new instruments in the area of security and defence, OSW, Warsaw 2019, pp. 9–10, osw.waw.pl/en.

[12] Strategic Compass – For a more coherent flexible and robust EU crisis management action, May 2021, club.bruxelles2.eu

[13] Capability Development Plan, European Defence Agency, 28 June 2018, eda.europa.edu.

[14] D. Fiott, ‘EU defence capability development. Plans, priorities, projects’, EUISS, 25 June 2018, iss.europa.eu.

[15] 2020 CARD Report. Executive Summary, op. cit.

[16] J. Gotkowska, ‘NATO 2030: towards a new strategy’, OSW Commentary, no. 398, 23 June 2021, osw.waw.pl/en.

[17] E. Hagström Frisell, E. Sjökvist, To Train and Equip Partner Nations – Implications of the European Peace Facility, Swedish Defence Research Agency, February 2021, foi.se.

[18] Article 42.7 of the Treaty on European Union: “If a member state is the victim of armed aggression on its territory, the other member states shall have towards it an obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in their power, in accordance with Article 51 of the United Nations Charter. This shall not prejudice the specific character of the security and defence policy of certain member states. Commitments and cooperation in this area shall be consistent with commitments under the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, which, for those states which are members of it, remains the foundation of their collective defence and the forum for its implementation”.

[19] G. Gressel, N. Popescu, ‘The best defence: why the EU should forge security compacts with its eastern neighbours’, European Council on Foreign Relations, 3 November 2020, ecfr.eu.

[20] N. Gros-Verheyde, ‘Pour six Européens, il faut déployer une mission de type EUTM pour aider l’armée ukrainienne’, B2 Pro, 1 September 2021, club.bruxelles2.eu.