High North, high priority – Norway and the defence of NATO’s northern flank

NATO's northern flank plays an increasingly important role in the security of the Euro-Atlantic area. Russia’s forces in the Northern Military District pose not only a conventional threat to Norway, but also a nuclear threat to the whole NATO, including the United States and Canada due to submarine-launched intercontinental ballistic missiles. The Russian Federation has been consistently increasing its military presence in the Arctic and its military activity along Norway's borders. Deterring Russia in the High North, in increasingly close cooperation with the allies, is thus a key task for the Norwegian Armed Forces. Oslo is gradually lifting Cold War restrictions in the defence sphere and intensifying military cooperation with the US, which is stirring up political controversy in the country. From the US perspective, NATO's northern flank is becoming more vital for containing Moscow. That is why they signed the Supplementary Defense Cooperation Agreement with Norway, expanding US troop access to military infrastructure there.

Challenges on NATO’s northern flank

NATO's northern flank stretches from the naval choke points between Greenland, Iceland and the United Kingdom up to the Arctic Ocean. Most of it is made up of Norwegian territories and maritime areas in the Arctic, namely the High North. It includes the northern regions of Norway (Nordland and Troms og Finnmark), the Svalbard archipelago, the island of Jan Mayen and the waters between the Greenland Sea and the Pechora Sea.

In the event of a Russia-NATO conflict, this area would become a theatre of war because of the conventional and nuclear capabilities of Russia’s Northern Fleet. Oslo is growing increasingly concerned as it watches the militarisation of the Russian Arctic and growing activity of the Russian Navy and Air Force along the Norwegian coast. In recent years, Russian manoeuvres in the High North have included Northern Fleet live-fire drills in the Norwegian exclusive economic zone, more frequent submarine operations, electronic warfare (GPS jamming during NATO's Trident Juncture 2018 exercise), and simulated airstrikes against targets in Norway.[1] The Russian Federation resumed long-range strategic bomber flights on NATO’s northern flank in 2007, and the number of its aircraft intercepted by Norway’s Quick Reaction Alert fighters has been increasing since 2014. These activities show that Moscow has returned to the offensive-defensive Bastion concept, i.e. shielding Russia’s second strike capability in the Barents Sea (the Northern Fleet’s nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines). Russian exercises show that the forward defence of the "bastion" would extend far beyond the Barents Sea – into the Norwegian Sea and northern Norway.[2] The Northern Fleet's underwater and anti-access capabilities (S-400 air defence and Bastion anti-ship systems, Kalibr and Kh-101/102 cruise missiles) could limit the US’s power projection to Europe and Norway through the maritime bottlenecks between Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom (GIUK).[3]

In peacetime, in turn, there is a risk of unconventional Russian warfare on the northern flank, targeting Norway. The High North is of significant economic importance to Norway, with rich oil and gas deposits and fishing grounds located there.[4] Oslo does not rule out regional tensions, during which Russia would test NATO's and Norway's response to hybrid operations, as during the migration crisis on the Norwegian-Russian border in 2015.[5] For a hybrid operation in the High North, the Russians could also use the demilitarised and neutralised Svalbard archipelago, which is part of the Kingdom of Norway. The status of the waters around Svalbard is disputed between Oslo and Moscow (but also the EU), with implications for fishing and resource extraction. Russia does not recognise Norway's exclusive rights to the continental shelf around the archipelago. In February 2020, on the centenary of the Svalbard Treaty, the Kremlin accused Norway of violating the interests of the Russian Federation and called for bilateral consultations on the archipelago.[6]

Norway: restricting the policy of self-imposed restrictions

In light of Russia's actions, Norway has for several years been gradually lifting the self-imposed military restrictions concerning its own forces and those of its allies. Set during the Cold War, these restraints were aimed at reducing tensions in Northern Europe by prohibiting the deployment of nuclear weapons and permanent allied forces in Norway and also put military exercises in the northern regions bordering the Soviet Union on hold. In addition, Oslo developed bilateral cooperation with the USSR/Russia in the areas of fisheries, cross-border contacts, resource extraction, and even military exercises. Changes to this policy introduced by Erna Solberg's centre-right government after the annexation of Crimea included agreeing to a rotational presence of the US Marines in central Norway from 2017–2020 and the holding of national and multinational exercises in the High North.[7] The defence of northern Norway was supposed to be rehearsed during the multinational Cold Response 2020 winter drills, which were cancelled due to the pandemic. When they are next held, in 2022, about 40,000 soldiers are expected to participate, and they will return to this Arctic-oriented scenario.[8] The focus on this area is also evident in naval exercises. In September 2020, a group of ships from the UK, US and Norway operated in Russia's exclusive economic zone off the Rybachy Peninsula, demonstrating the readiness to ensure freedom of navigation in the Barents Sea.[9] For the Norwegian Navy, these were the first ever activities so close to Russian territory. Oslo used to recognise the 28th meridian east (eastern Finnmark) as the borderline for national exercises, and the 24th meridian east (western Finnmark) for the allied ones.

Hosting US rotational forces and moving military exercises closer to Russia's border is perceived by some commentators and the Norwegian left wing as controversial and as the de facto withdrawal from the policy of self-imposed military restrictions. Against this background, there are calls for a sharp increase in defence spending to reduce the dependence on the United States in the area of national security, or for a return to dialogue and confidence-building measures in relations with Russia.[10] Opponents of closer cooperation with the US argue that the Kremlin perceives this as a direct threat to the Northern Fleet and that Oslo is limiting its room for political manoeuvre, making itself a hostage to the rivalry between Washington and Moscow. Reconciling support for US and NATO activities in the High North with the desire to keep this region outside international tensions will be one of the major dilemmas of Norway’s security policy in the decade ahead.

Notwithstanding these problems, most Norwegian policymakers and political parties are aware that Norway would not be able to defend itself on its own. That is why deterrence and collective defence in NATO (Oslo is seeking to strengthen NATO’s maritime domain) and cooperation with its closest allies, mainly the US and the UK, are essential components of Norway’s strategic culture.[11] Norway perceives the United States as the main guarantor of its security, seeing no alternative to the bilateral military cooperation that has been developed for decades. Therefore, it seeks the visible presence of US forces. There are many indications that Oslo will aim to take advantage of Washington's growing interest in the Arctic to further develop this bilateral cooperation.[12] It is also strengthening its relationship with London on anti-submarine warfare as a future operator of P-8 aircraft and on amphibious exercises (often together with its Dutch counterpart). The Norwegian Armed Forces also contribute to the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF). The UK and the Netherlands are interested in prepositioning equipment for the marines at the Olavsvern base in the High North.[13] Oslo also lists Germany, Sweden and Finland among the first-tier directions for military cooperation.

The US in the High North

In recent years, the United States has strengthened its military presence in the High North as part of its policy of containing Russia in the Arctic. Between 2019 and 2021, the Department of Defense and the branches of the US military have adopted their Arctic strategies. They point to the importance of cooperation with Norway in monitoring the North Atlantic, Arctic exercises and bolstering the military interoperability of the two countries.[14] In April this year, Washington and Oslo signed a Supplementary Defense Cooperation Agreement (SDCA), updating numerous previous bilateral arrangements and the NATO Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA).[15] It lays down the issues related to the presence, training and exercises of US troops in Norway in detail. Under the SDCA they will be able to use the Agreed Facilities and Areas at the Rygge and Sola air force bases (in southern Norway) as well as the Evenes air force base and Ramsund naval base (in northern Norway). The agreement is set to enhance US-Norway cooperation in the air defence and maritime domain and to enable the faster deployment of US troops to Norway, should such a need arise. The NATO Trident Juncture 2018 collective defence exercise, in which 20,000 US soldiers took part, clearly demonstrated that US forces would play a decisive role in the defence of the northern flank.

The US Marines exercises and training in Norway is the most visible element of the military cooperation between the two countries. After the annexation of Crimea, the amount of armament and military equipment stored in Norway under the Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway was increased. Currently, these stocks are sufficient to equip a Marine Expeditionary Brigade with a 30-day supply of munitions.[16] In 2017 the Americans deployed a rotating contingent of 330 Marines to Norway. A year later this was doubled, and in 2020 it was reduced to just 20 soldiers, which is related to the reform of the entire US Marine Corps (USMC).[17] At that time, the decision was made to replace the six-month rotations with annual larger-scale Marines exercises in Norway. These changes have fuelled Oslo's concerns about the future of US military engagement in Europe and Norway. Indeed, the USMC's new concept aims at pivoting the formation towards Asia and phases out tanks and the capabilities needed to conduct large amphibious assaults. However, the USMC still recognises the strategic importance of Norway, including in the context of new tasks for the formation, such as anti-submarine warfare. To that end, it is considering establishing a network of "mobile bases" in Norway with prepositioned equipment.[18]

Bilateral cooperation also includes the air force: exercises and training under the F-35 program. The US is a strategic partner of Norway and the other Nordic countries in conducting the largest European air force exercise, Arctic Challenge, held in the north of the Scandinavian Peninsula. From February to April this year, Norway's Ørland Air Base hosted US B-1 bombers, which performed flights with Norwegian F-35s and a number of training missions on NATO's northeastern flank, including Poland and the Baltic states. The navies of both countries are also exercising more often in the High North. The region is expected to play an important role in exchanging crews and resupplying nuclear-powered American submarines operating in the Arctic. Despite local controversy, in 2020, Norway completed the adaptation of the port of Tromsø to accommodate allied submarines. In August 2020, the most advanced American nuclear submarine (Seawolf-class) surfaced there.[19] Additionally, the US infrastructure for its Navy's P-8 maritime patrol aircraft will be built at Evenes Air Base. This shows that it wishes to enhance its capability to detect and combat Russian submarines in the High North.[20] Finally, bilateral intelligence cooperation, focused on monitoring the activities of the Northern Fleet, is vital. Norway is described as NATO's "eyes and ears" in the region, which results from its reconnaissance and surveillance capabilities in the Barents Sea and the Arctic (electronic intelligence vessels and the Globus III military intelligence radar in Vardø).

The High North: a priority for Norway's Armed Forces

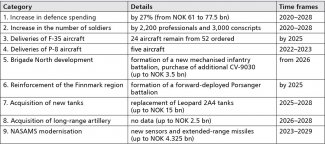

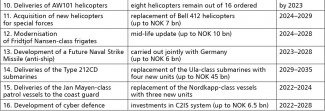

The defence of the High North has become the priority of the Norwegian Armed Forces (11,900 professional soldiers, 9,600 conscripts and 39,100 members of the territorial defence). Apart from developing their own capabilities to fight in the Arctic, they are investing in the readiness to receive NATO reinforcements (Host Nation Support) in the northernmost regions and to secure sea and land lines of communication (from the south to the north of the country), as well as in interoperability with NATO forces.[21] The focus on the Arctic is evident not only in operational planning, but also in the new long-term modernisation plan for the Armed Forces for 2020–2028, adopted in December 2020. It envisages an increase in defence spending by NOK 16.5 billion (about $2 billion), continuing the trend of recent years. In response to Russia's aggression against Ukraine and its increased military activity in the High North, from 2014 to 2020 Norway increased its defence budget from NOK 47 to NOK 61 billion (from $5.8 to $8 billion), or from 1.5 to 2 percent of GDP.[22] Nevertheless, the opposition and the expert community have criticised the long-term plan not to sufficiently increase the number of soldiers or not to include long-range air defence systems in acquisitions, arguing that it will not bring a significant boost for Norway’s military capabilities and will not reduce tensions between tasks related to territorial defence and ongoing contributions to international operations.[23]

After focusing on the Navy and Air Force capabilities in the previous modernisation cycles, Norway's priority until 2028 will be to strengthen the Land Forces. These are largely being postured for Arctic warfare.[24] The biggest beneficiary of the Long-Term Defence Plan will be the Brigade North – the army's main military formation. It is located in Troms og Finnmark county (with the exception of the only fully professionalised expeditionary battalion Telemark, which is stationed in southern Norway). This brigade will be expanded with an additional combat battalion. In addition, Norway will continue to form a new battalion at Porsangmoen to reinforce the land border with Russia. However, the majority of investments are scheduled to fall in the second half of the decade, as the F-35 program will continue to absorb the bulk of equipment spending in the coming years. From the perspective of the defence of the High North, putting more money into the Land Forces seems indispensable. They are struggling with an insufficient number of troops and a low level of combat readiness – the army can quickly deploy only a battalion-size battlegroup.[25] Contrary to the hopes of the military leadership, which called for an increase in defence spending by NOK 25 billion, the adopted financial framework will not enable the establishment of a second brigade in the central and southern parts of the country.

The High North is a key area of responsibility for the Norwegian Navy and Coast Guard (which is part of the Navy).[26] Their tasks in the region include safeguarding the exclusive economic zone, escorting NATO ships and patrolling the waters between the north of the country, Bear Island and the Svalbard archipelago.[27] For the Northern Fleet, including submarines, the exits from the Barents Sea to the Norwegian Sea lead through these waters. Considering the naval presence in the High North, the crucial modernisation program concerns the purchase of new submarines, which will enter service from 2029 onwards. Norway will also invest in maritime helicopters used in the Barents Sea and vessels for the coast guard. The Skjold-class corvettes will be equipped with additional long-range anti-ship missiles (NSM). However, the Navy's capabilities are hamstrung by personnel shortages and the loss of a frigate during the Trident Juncture 2018 exercises. In the High North, it is supported by the Air Force, which is involved in patrolling maritime areas and anti-submarine warfare. From 2022, these tasks will be carried out by new P-8 maritime patrol aircraft. Norway will also invest in military communications solutions, including satellite and link infrastructure, for the forces detached to the northern part of the country.

APPENDIX

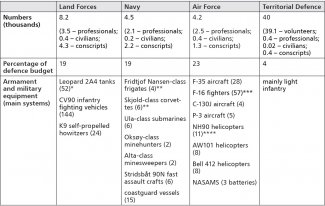

Table 1. Armed Forces of the Kingdom of Norway in numbers, 2020

* Of which less than 40 are operational.

** Armed with Naval Strike Missiles.

*** Of which about half are operational. Norway’s F-16s will be withdrawn from service in 2021.

**** Of the 14 ordered. The maritime helicopter program is significantly delayed. Norway is considering leasing other helicopters to fill this gap.

Sources: ‘Forsvaret i tall’, Norwegian Armed Forces, 14 April 2021, forsvaret.no; J. Gustafsson, ‘Norway’, op. cit.

Table 2. Norway's defence spending in 2013–2020 according to NATO

![]()

Source: ‘Defence Expenditures of NATO Countries (2013–2020)’, NATO, 16 March 2021, nato.int.

Table 3. Norway’s Long-Term Defence Plan (2020–2028, selected aspects)

Source: ‘Framtidige anskaffelser til forsvarssektoren (FAF) 2021–2028’, Government of the Kingdom of Norway, 22 April 2021, regjeringen.no.

[1] T. Nilsen, ‘Russian bombers simulated an attack against this radar on Norway's Barents Sea coast’, The Barents Observer, 5 March 2018, thebarentsobserver.com; Idem, ‘11 Russian fighter jets made mock attack on Norwegian Arctic radar’, ibid, 12 February 2019.

[2] Unified Effort, Ministry of Defence of the Kingdom of Norway, 2015, regjeringen.no.

[3] R. Allport, Fire and Ice. A New Maritime Strategy for NATO's Northern Flank, Human Security Centre, December 2018, hscentre.org.

[4] In the future, Norwegian maritime areas in the Arctic could play a greater role in international trade, as prospective shipping routes pass through them. J. Gotkowska, Norway and the Bear. Norwegian defence policy – lessons for the Baltic Sea region, OSW, Warsaw 2014, osw.waw.pl.

[5] P. Szymański, P. Żochowski, W. Rodkiewicz, ‘Enforced cooperation: the Finnish-Russian migration crisis’, OSW, 6 April 2016, osw.waw.pl.

[6] Further allegations include: Norway's adoption of new environmental regulations on Svalbard, which Russia believes are detrimental to its economic interests; unfair deportation procedure; imposing restrictions on the use of Russia’s helipad and helicopter; and its favouritism of Longyearbyen's development over Russian Barentsburg. See A. Staalesen, ‘Norway's celebration of Svalbard Treaty was followed by ardent and coordinated response from Moscow media’, The Barents Observer, 2 July 2020, thebarentsobserver.com.

[7] J. Gotkowska, ‘US Marines in northern Norway’, OSW, 20 June 2018, osw.waw.pl.

[8] Facts about exercise Cold Response 2020, Norwegian Armed Forces, 2020, as cited in: evenes.kommune.no; T. Nilsen, ‘Norway to host biggest exercise inside Arctic Circle since Cold War’, The Barents Observer, 14 April 2021, thebarentsobserver.com.

[9] T. Nilsen, ‘In a controversial move, Norway sails frigate into Russian economic zone together with U.K. and U.S. navy ships’, The Barents Observer, 8 September 2020, thebarentsobserver.com.

[10] For more see T. Heier, Norden som lavspenningsområde – hva kan Norge gjøre?, Norges Fredsråd, September 2020, norgesfredsrad.no.

[11] For Oslo it was of great value to test the collective defence of Norway and the northern flank during the large-scale Trident Juncture 2018 NATO exercise, which involved 50,000 troops.

[12] F. Bakke-Jensen, ‘Norway’s defense minister: We must ensure strategic stability in the High North’, Defense News, 11 January 2021, defensenews.com.

[13] J. Falnes, ‘Nederlandsk styrke får bruke Olavsvern’, Forsvarets Forum, 23 November 2020, forsvaretsforum.no.

[14] Department of Defense’s Arctic Strategy, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, June 2019, defense.gov.

[15] ‘Norway signs Supplementary Defense Cooperation Agreement with the United States’, Government of the Kingdom of Norway, 16 April 2021, regjeringen.no.

[16] The brigade consists of an infantry battalion task force, combat logistics battalion, and aviation squadron. T.F. Hacker, Defense Primer: Department of Defense Pre-Positioned Materiel, Congressional Research Service, 9 December 2020, congress.gov.

[17] A. Rognstrand, ‘Fra 650 til rundt 20 US Marines i Norge mellom øvelser’, Forsvarets Forum, 23 July 2020, forsvaretsforum.no.

[18] D. Berger, ‘Marines Will Help Fight Submarines’, U.S. Naval Institute, November 2020, usni.org.

[19] T. Nilsen, ‘U.S. Navy's most advanced attack submarine surfaced outside Tromsø’, The Barents Observer, 25 August 2020, thebarentsobserver.com.

[20] P. Szymański, USA–Norwegia: wzmocniona obecność wojskowa USA na północnej flance NATO, OSW, 22 April 2021, osw.waw.pl.

[21] T. Heier, ‘Norway's Military Strategy After the Cold War: Between Demise and Revival’ [in:] J.H. Matlary, R. Johnson (eds.), Military Strategy in the Twenty-First Century: The Challenge for NATO, Hurst, 2020, pp. 433–453.

[22] It is also revitalising its total defence system by strengthening civil defence and critical infrastructure in the High North.

[23] Norway reformed its Armed Forces 20 years ago by moving away from the mobilisation model to the development of operational forces. Between 2000 and 2005, they were reduced by a third, and the defence ministry was increasingly looking for savings. Currently, Norway’s four most important foreign deployments are in Afghanistan (NATO Resolute Support, 100 soldiers), Iraq, Qatar and Jordan (the US-led Operation Inherent Resolve, 130 soldiers), Lithuania (NATO eFP, 140 soldiers) and Mali (UN MINUSMA, 85 soldiers). A total of 32 soldiers are involved in the other missions.

[24] ‘Enighet om langtidsplanen for forsvarssektoren’, Government of the Kingdom of Norway, 1 December 2020, regjeringen.no.

[25] J. Gustafsson, ‘Norway’ [in:] E. Hagström Frisell, K. Pallin (eds.), Western Military Capability in Northern Europe 2020. Part II: National Capabilities, FOI, February 2021, pp. 27–38.

[26] Although Norway has suspended most military cooperation with Russia, it continues joint activities in maritime search and rescue.

[27] R. Allers, P.S. Hilde, ‘Norway’ [in:] T. Rostoks, G. Gavrilko, Defence Policy and the Armed Forces in Times of Pandemic, Konrad Adenauer Foundation, National Defence Academy of Latvia, Riga 2020, pp. 179–191.