The northern tandem. The Swedish-Finnish defence cooperation

In response to the change in the security environment after 2014, militarily non-aligned Sweden and Finland are developing their defence cooperation with NATO and the USA and strengthening their bilateral defence relationship. Although a bilateral alliance is unlikely, the two states are suggesting that, were a situation of a conflict in the Nordic-Baltic region to occur, the hypothetical aggressor will need to take into account their cooperation and joint actions with NATO. The Northern Wind 2019 exercises carried out in March 2019, whose scenario includes the defence of northern Sweden, are a display of the interoperability of the Swedish and Finnish armed forces. However, the military synergy between Sweden and Finland is limited by the differences in their respective models of armed forces, years-long insufficient defence expenditure, and military personnel cuts.

Military cooperation and defence policies of Sweden and Finland

The Russian-Ukrainian war, the development of Russia’s military potential and the increase in NATO’s and the US’s military presence in the Nordic-Baltic region have all contributed to a redefinition of the security policies of Sweden and Finland. Sweden, which used to focus on global threats, began to place greater emphasis on security in the Baltic Sea region and to rebuild its capability of defending its own territory. Finland, for its part, which traditionally used to be focused on maintaining its independent defence capability, opened up to providing and receiving military assistance. It should be noted that neither Sweden nor Finland have made attempts to join NATO, but they have strengthened their military cooperation with NATO as a whole and with those of its members that are of key importance in the context of defending the northern flank, i.e. mainly the USA but also the United Kingdom. The adoption of a more ambitious programme of Swedish-Finnish defence cooperation was another element complementing these actions.

In May 2014, the two states announced their Action Plan for Deepened Defence Cooperation, a framework document heralding the development of cooperation between all branches of the armed forces and the defence ministries[1]. The final report on deepened defence cooperation between Finland and Sweden compiled a year later specified six key cooperation areas[2]. These include: cooperation of the navies, the air forces, the land forces, cooperation in logistics and in the supply of matériel, international cooperation (joint participation in crisis management operations and multinational forces) and cooperation in ensuring secure communication between the armed forces and the defence ministries.

The tightening of Swedish-Finnish defence cooperation is facilitated by the common political, military and economic interests of the two states.

The framework memorandum of July 2018 is a political document that forms the basis for bilateral defence cooperation during peacetime, crisis, and wartime[3]. The memorandum does not set any limitations on developing military cooperation, nor does it contain any formal mutual defence obligations. The current bilateral cooperation areas were supplemented with host nation support (HNS), protection against weapons of mass destruction and hybrid threats, and strategic communication.

Reasons for a military rapprochement between Sweden and Finland

Aside from unfavourable changes in the security environment connected with the tension between Russia and NATO, catalysts for the development of Swedish-Finnish defence cooperation include the common political, military and economic interests of the two states.

Political reasons: For Sweden and Finland, the development of bilateral defence cooperation is politically convenient because it does not raise controversy in their parliaments nor within their societies the way military cooperation with NATO and with the USA does. Strengthening defence ties with a militarily non-aligned partner does not require any fundamental revision of the current security policy, the foundation of which is to remain outside military alliances. Building joint military capabilities and developing international cooperation is partly treated (especially in Sweden) as compensation for insufficient military spending[4]. Moreover, the increasingly close Swedish-Finnish cooperation is bringing benefits such as interest on the part of Washington in developing trilateral collaboration. This was evident in the Trilateral Statement of Intent regarding defence cooperation between the USA, Sweden and Finland, announced in May 2018[5]. The trilateral format and the expansion of Swedish-American military relations carried out by the leftist government in Stockholm facilitate the process of Finnish centre-left political parties ‘growing accustomed’ to the idea of military cooperation with the USA. These parties continue to value the heritage of the Cold War policy of non-involvement in the rivalry between the great powers, and are reluctant to compromise Finland’s relations with Russia.

Military reasons: It is highly likely that, in the case of a conflict in the Baltic Sea region, the operational activity of the Swedish armed forces would concentrate in the most densely populated southern part of the country. This area is of key importance for maintaining strategic locations (e.g. Gotland), ensuring the capability of hosting NATO troops and organising the transit of NATO assistance for the Baltic states[6]. In this scenario, Sweden would not have sufficient forces at its disposal to defend the northern part of the country, or to conduct forward defence operations in the Baltic states and in Finland. Hence the importance of Finland as a country securing the northern flank and the Swedish interest in bilateral military cooperation[7]. According to Sweden’s defence strategy for 2016–2020, adopted in 2015, it is crucial to tighten the country’s cooperation with Finland, as it is intended to result in joint operational planning and preparations for the defence of the territory of both states[8].

Both states form a common strategic space and, during a conflict with Russia, Sweden could play an important role in Finland’s defence operations.

From Helsinki’s point of view, the two states form a common strategic space, which is why Sweden is Finland’s major partner in foreign and security policy[9]. Finland does not intend to introduce limitations in its defence cooperation with Sweden. It would like the gradual coordination of defence policies and the high level of armed forces interoperability in peacetime to translate in the future into a joint wartime operational plan. During a conflict with Russia, Sweden could play an important role in Finland’s defence operations (joint military actions, matériel and raw material supplies, ensuring the transit of potential military aid from other states). This is due to Sweden’s geographical location, which places it at the centre of any potential conflict in the Baltic Sea region, including as the logistic and military hub of NATO’s operations. Cooperation with Sweden also entails an increased capability to defend the Åland Islands which have demilitarised and neutralised status.

Economic reasons: The development of bilateral defence cooperation is also intended at generating budget savings by joint international involvement, joint military capabilities, and the procurement of armament and military equipment. Cooperation between the respective branches of armed forces is intended to enable the participation of joint units in crisis management operations: for example the Swedish-Finnish Naval Task Group, the land forces brigade, the NH90 helicopter unit and military logistics. Closer Swedish-Finnish cooperation is in the interest of the strong Swedish defence industry, which is an important supplier of armament and military equipment for the Finnish armed forces. After 2000, the armament and military equipment Finland bought from Sweden included infantry fighting vehicles (the purchase of 102 CV9030 with a 50% offset), armoured personnel carriers, anti-ship, anti-aircraft and anti-tank missiles, naval guns and radars[10]. However, Finland has a cautious approach to joint modernisation projects, fearing the domination of Swedish companies and aiming to protect its own defence industry that mainly produces armament and equipment for land forces. Sweden’s withdrawal from the purchase of the co-developed AMOS mortar programme (Patria and Hägglunds) was another negative experience. At present, Sweden and Finland are implementing a joint project involving the development and purchase of light anti-submarine torpedoes, the Torpedsystem 47 (they will be carried by new Finnish vessels)[11].

In the air, at sea and on land: the cooperation of armed forces

After 2014, Sweden and Finland focused mainly on ensuring the full interoperability of their air and naval forces[12]. Their cooperation includes an advanced exercise programme, the ability to use each other’s bases, access to each other’s territory, and the capability to build a combined unit and to transfer operational command.

The scenarios of Swedish-Finnish military exercises increasingly often focus on joint defence operations in a high-end conflict.

The two countries’ navies intend to create a Swedish-Finnish Naval Task Group (SFNTG). The air forces, for their part, are expected to achieve a level of interoperability which would enable them to carry out joint operations with the full spectrum of capabilities (ensuring air superiority and providing air support to other branches of armed forces). In 2018–2019, there was an increase in cooperation between land forces, which previously had been less prominent. It focuses on developing the concept of a combined brigade and an expanded exercise programme. Although military cooperation still lacks common wartime planning, Swedish-Finnish military exercises are increasingly moving away from crisis management scenarios towards simulating joint defence operations in a high intensity conflict.

Air forces. Cross-border exercises of the air forces of Sweden, Finland and Norway under the Nordic cooperation framework are organised almost weekly (Cross Border Training)[13]. A few times annually they are expanded to include the participation of the USA. At the same time, Sweden and Finland are implementing their bilateral training programme within the co-operation between the Finnish and Swedish Air Forces (FISE). Since 2016, the two countries’ fighter jets have participated in their main national air force exercises: Ruska in Finland and Flygvapenövning in Sweden. Increasingly often Finnish jets carry out their operations from bases located in Sweden and vice versa, including reserve and road bases. Initially, during exercises, the two countries’ jets performed opponent roles, but since 2017 they have also practised joint air defence tasks[14].

Navies. The joint Swedish-Finnish Naval Task Group (SFNTG) reached its initial operational capability in 2017. Its regular patrolling activity is planned for the next few years[15]. One example of the SFNTG’s composition includes a staff element and several vessels, for example the Swedish Visby-class corvette and the Finnish Hamina-class missile boat, mine countermeasures vessels and minelayers, landing crafts and auxiliary ships. Since 2015, as part of the implementation of the SFNTG concept, both navies have carried out annual bilateral exercises (SWEFINEX/FINSWEEX). The SFNTG participates in multinational manoeuvres on the Baltic Sea (Baltops, Northern Coast and Aurora). The scenarios of bilateral naval exercises were expanded to include anti-submarine warfare, because in 2014–2015 both states recorded incidents involving alien underwater activity in their territorial waters. Unlike Finland, Sweden does have submarines, which increases the attractiveness of this type of exercise for the Finnish side[16]. Moreover, the necessity to develop capabilities for operations in archipelagic waters (both states have a skerry coastline) is a spur to cooperation between marines units (Amfibieregementet and Uudenmaan prikaati) under the Swedish-Finnish Amphibious Task Unit (SFATU).

The Swedish-organised Northern Wind 2019 exercises boost the importance and the scale of cooperation between the land forces of Sweden and Finland.

Land forces. Cooperation between the land forces has so far been less prominent. Its development was hamstrung by divergent priorities – Sweden’s priority involved participation in crisis management operations whereas Finland’s priority was the training of conscripts. This is why after 2014 the cooperation of land forces, focusing on territorial defence, is de facto being built from scratch[17]. Until recently, this limited cooperation was carried out mainly by the northernmost tactical formations (the Swedish Norrbotten regiment and the Finnish Jääkäriprikaati and Kainuun prikaati), where joint land forces action would be the most favourable in case of a conflict. Cooperation between the land forces gathered momentum during NATO’s Trident Juncture manoeuvres organised in Norway in 2018, which was the first time a Finnish unit took part in exercises integrated into a Swedish brigade[18]. The Swedish-organised Northern Wind 2019 exercises carried out in March 2019 have been another initiative that boosted the importance and the scale of cooperation between the two armies. Under these exercises, a Finnish battalion-size battlegroup with an armoured component (1,500 troops and 500 vehicles) formed part of a Swedish brigade that carried out exercises with forces from the USA, the United Kingdom and Norway[19]. Since 2016, the cooperation of the land forces has included joint exercises carried out by urban warfare infantry battalions responsible for the defence of the capital cities.

Other areas. Aside from the cooperation of the respective branches of armed forces, the Swedish-Finnish defence cooperation also includes close contacts between defence ministries and command headquarters (annual talks between chiefs of staffs of land forces and chiefs of logistics). Both states are building mutual trust by way of a programme of exchange of officials and military personnel. They also invest in secure communication between their defence ministries and armed forces (the flow of classified information, improved situational awareness) and cooperation in cyber-security.

Towards a defence union?

Unless further negative changes in the two states’ security environment happen (e.g. the disintegration of NATO, the US’s withdrawal from NATO’s northern and eastern flanks, the erosion of European integration) then no serious debate on a bilateral defence alliance should be expected[20]. In the upcoming years, Sweden and Finland will focus their bilateral cooperation on: ensuring a high level of interoperability of all branches of armed forces, building a common situational awareness, and coordinating defence policies and wartime planning. These ‘special relations’ will form an important element of both states’ strategic communication. On the one hand, their openness to military cooperation with NATO and the USA, including joint exercises, is proof of their readiness to act jointly with NATO in the case of a conflict in the region. On the other hand, Stockholm and Helsinki would like Moscow to perceive their bilateral military cooperation as an informal alliance and a sign that they are willing and able to carry out joint defence actions.

The Finnish national defence exercises planned for 2021 (modelled on Sweden’s Aurora 17 exercises) will be an opportunity to verify the progress in bilateral defence cooperation and set new goals. They will demonstrate which forces and in which directions Stockholm would be able to engage in operations involving the defence of Finland. Also in 2021 Finland will make a decision regarding the purchase of new fighter jets which it plans to spend up to 10 billion euros on. Sweden has offered its JAS 39E Gripen fighter aircraft and will surely use economic and military arguments to lobby for SAAB’s bid (emphasising, for example: interoperability issue, the preparation of Swedish bases to service Gripen jets, the adjustment of the aircraft to the conditions in the Nordic-Baltic region, the quick repair options).

APPENDIX

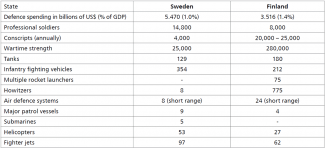

The armed forces of Sweden and Finland

Source: compiled on the basis of the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex, websites of the armed forces of Sweden and Finland, http://puolustusvoimat.fi/en/exchange-of-information, https://www.forsvarsmakten.se and The Military Balance 2018, IISS, London 2018.

[1] Action Plan for Deepened Defence Cooperation, Ministry of Defence of Finland, May 2014, https://www.defmin.fi/files/2833/ACTION_PLAN_FOR_DEEPENED_DEFENCE_COOPERATION_BETWEEN_SWEDEN_AND_FINLAND.pdf

[2] Final reports on deepened defence cooperation between Finland and Sweden, Ministry of Defence of Sweden, May 2015, https://www.government.se/49baf3/globalassets/government/dokument/forsvarsdepartementet/final-reports-on-deepened-defence-cooperation-between-finland-och-sweden.pdf

[3] Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the Republic of Finland and the Government of the Kingdom of Sweden on Defence Cooperation, Ministry of Defence of Sweden, July 2018, www.government.se/49fcef/globalassets/government/dokument/forsvarsdepartementet/2018/mou-finnish-swedish-defence-cooperation-20180625-signerad.pdf

[4] J. Gotkowska, Szwedzko-fiński sojusz wojskowy?, “Analizy OSW”, 14 May 2014, https://www.osw.waw.pl/pl/publikacje/analizy/2014-05-14/szwedzko-finski-sojusz-wojskowy

[5] Trilateral Statement of Intent, Ministry of Defence of Finland, May 2018, https://www.defmin.fi/files/4231/Trilateral_Statement_of_Intent.pdf

[6] K. Neretnieks, NATO and Scandinavian Strategic Interdependence, “Karlis N”, 4 October 2018, http://karlisn.blogspot.com/2018/10/nato-and-scandinavian-strategic.html?spref=tw

[7] Despite the fact that Finland’s operation would focus on the southern part of the country, as with Sweden.

[8] Sweden’s Defence Policy 2016 to 2020, Ministry of Defence of Sweden, 1 June 2015, https://www.government.se/globalassets/government/dokument/forsvarsdepartementet/sweden_defence_policy_2016_to_2020

[9] Government Report on Finnish Foreign and Security Policy, Prime Minister’s Office Publications, 2016, https://valtioneuvosto.fi/documents/10616/1986338/VNKJ092016+en.pdf/b33c3703-29f4-4cce-a910-b05e32b676b9; Government’s Defence Report, Ministry of Defence of Finland, 2017, https://www.defmin.fi/files/3688/J07_2017_Governments_Defence_Report_Eng_PLM_160217.pdf

[10] Whereas the equipment that Sweden bought from Finland included 280 Patria AMV and Pasi armoured personnel carriers (100% offset). V. Suominen, Driving Forces Influencing Debate on Intensified Finnish-Swedish Defence Cooperation, Swedish National Defence College, 2014, http://fhs.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:720415/FULLTEXT01.pdf

[11] R. Häggblom, Torped 47 – Steel fishes back into Finnish service, “Corporal Frisk”, 1 May 2018, https://corporalfrisk.com/2018/05/01/torped-47-steel-fishes-back-into-finnish-service/

[12] The close cooperation between the navies of the two states has had the longest tradition among all branches of the armed forces, reaching back to the 1990s. C. Salonius-Pasternak, Deeper Defence Cooperation: Finland and Sweden Together Again?, FIIA, 3 Decemeber 2017, https://storage.googleapis.com/upi-live/2017/01/bp163.pdf

[13] International Activities Develop Air Force Capability, Finnish Air Force, https://ilmavoimat.fi/en/international-cooperation

[14] Ruska 17 and Baana 17 exercises taking place in October, Finnish Air Force, 22 September 2017, http://ilmavoimat.fi/en/article/-/asset_publisher/ilmaoperaatioharjoi-tus-ruska-17-ja-lentotoimintaharjoitus-baana-17-jarjestetaan-lokakuussa; Finnish Defence Forces, Finnish Air Force to Take Part in Sweden’s Flygvapenövning 18, 14 May 2018, https://puolustusvoimat.fi/en/article/-/asset_publisher/1951206/ilmavoimat-mukana-ruotsin-flygvapenovning-18-ilmaoperaatioharjoituksessa

[15] J. Adamsson, From one exercise to the next, Swedish Armed Forces, 22 September 2017, https://www.forsvarsmakten.se/en/news/2017/09/from-one-exercise-to-the-next/; Finnish Defence Forces, Finland and Sweden to participate in joint naval exercise, 25 April 2016, https://puolustusvoimat.fi/en/article/-/asset_publisher/1951215/ruotsalais-suomalaisen-merellisen-taisteluosaston-alusyksikot-yhteisharjoitukseen

[16] The exercises carried out by the navies also include artillery firing, amphibious assaults and mine countermeasures. Cooperation also includes sea surveillance.

[17] J. Sundström, Finnish soldiers exercising in Boden, Swedish Armed Forces, 30 November 2015, https://www.forsvarsmakten.se/en/news/2015/11/finnish-soldiers-exercising-in-boden/; The cooperation between the Finnish and Swedish Armies progresses, Finnish Army, 22 June 2016, https://maavoimat.fi/en/article/-/asset_publisher/suomen-ja-ruotsin-maavoimien-valinen-yhteistyo-kehittyy

[18] M. Nilsson, Svenskt-finskt samarbete i Norge, Swedish Armed Forces, 29 October 2018, https://www.forsvarsmakten.se/sv/aktuellt/2018/10/svenskt-finskt-samarbete-i-norge

[19] Northern Wind: Swedish Army Exercise 2019, Swedish Armed Forces, https://www.forsvarsmakten.se/en/activities/exercises/northern-wind/; Northern Wind 2019 Exercise in Northern Sweden, Finnish Army, https://maavoimat.fi/en/northernwind19-en

[20] In fact, neither state needs any additional guarantees in order to conduct joint military actions in case of conflict. They can invoke Sweden’s declaration of solidarity, the EU’s mutual assistance clause and Finland’s readiness to provide and receive military aid stipulated in the law.