Germany: the 2026 budget and rising debt

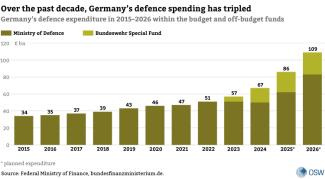

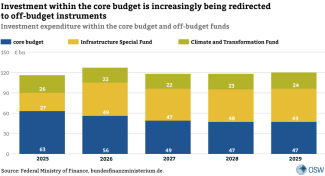

The federal budget for 2026, adopted by the Bundestag, envisages expenditure of €524.5 billion – €21.5 billion more than in 2025 (see ‘Germany’s budget: increased investment and debt’) – made possible by further increases in borrowing, which will rise by €98 billion next year. As in previous years, the largest share is allocated to social welfare benefits (mainly pension subsidies), accounting for 38% of total expenditure. A significant increase has been recorded in defence spending, which will amount to €83 billion (see Chart 1). An additional €25.5 billion for this purpose will come from the off-budget Bundeswehr Special Fund, reflecting plans to modernise the armed forces. Funding for military assistance to Ukraine has also been increased by €3 billion, bringing the total to €11.5 billion in 2026. By contrast, the government’s financial plan for 2025–2029 envisages a reduction in investment spending: in 2026 it will amount to €56 billion, compared with €63 billion in 2025 (see Chart 2).

Record-high borrowing still does not provide sufficient funding for new expenditure, particularly investment. The government faces accusations of creative accounting: according to the Ifo Institute, of the ten largest investment items in the core budget (€24.4 billion), only €5.8 billion will in fact be used for infrastructure projects. Although rising public spending in the defence industry is generating a modest economic uptick, the sector is far too small to compensate for the difficulties faced by other branches of the economy.

Commentary

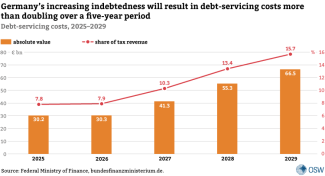

- Despite taking on record levels of debt, Germany still lacks the funds required for new expenditure. According to calculations by the Federal Ministry of Finance, public debt will reach the equivalent of 80.25% of GDP by 2029 (compared with 62.5% today), and Germany risks being placed under an excessive deficit procedure in 2026 and 2027. By 2029, the cost of servicing public debt is expected to double (see Chart 3). At the same time, the government is financing electoral pledges that do not stimulate economic activity – such as reducing VAT on restaurant meals, expanding the so-called ‘mother’s pension’, and raising subsidies for agricultural diesel. These measures cost the budget almost €10 billion annually. Consequently, public debate increasingly highlights that the financial plan for the coming years is based on creative bookkeeping and efforts to avoid cuts. Experts emphasise that the main problem for public finances is not tax revenue – which continues to grow steadily (reaching €387.2 billion in 2026) – but rapidly rising expenditure. The key task for the Finance Ministry is to reduce the budget deficit projected for 2027, estimated at €34.4 billion. By reallocating reserves, revising tax forecasts, and employing similar manoeuvres, the government plans to reduce it to approximately €12 billion.

- Plans to stimulate the economy are being undermined by the diversion of a large share of investment funds from the Infrastructure Special Fund (valued at €500 billion over 12 years). The fund was intended to finance additional investments that could not be covered by the regular budget. Its creation was enabled by a rule requiring that at least 10% of budget expenditure be allocated to investment, which was designed to prevent funds from being redirected to finance consumption-oriented electoral promises. According to the German Economic Institute (IW Köln), as much as half of the fund’s planned expenditure in the coming years may fail to meet the criterion of ‘additionality’, while the 10% threshold is seen as too low (in 2024, 11% of budget expenditure went to investments). This is evident in the case of the Federal Ministry of Transport: it received €45 billion from the core budget in 2024, €38 billion in 2025, and will receive only €28 billion in 2026. The ministry will receive an additional €21 billion from the fund; however, these resources may be used solely for maintaining and upgrading existing infrastructure.

- The rise in defence spending is prompting automotive and machinery suppliers to shift part of their operations into the defence sector. According to the Federation of German Security and Defence Industries, since November 2024 the number of member companies has risen from 243 to 440, with most of the new entrants originating from the small and medium-sized enterprise sector. Growing public procurement in the arms industry – offering stable, long-term contracts – enables these companies to partially offset declining revenues resulting from fewer orders in other sectors. By 2029, Germany’s defence spending within NATO is expected to reach 3.56% of GDP (with 2.83% planned for 2026), owing to the exemption of military expenditures from fiscal rules that restrict new borrowing (see ‘Agency on credit. Germany releases the debt brake’). This provides companies with greater predictability when planning their operations and orders.

![[Q&A] Skąd taka niechęć Niemców do atomu? Co myślą o cyfrowym zapóźnieniu? Jak oceniają Merkel?](/sites/default/files/styles/media_360_200_s_c/public/oembed_thumbnails/l1EiVo2dQ4LGIQHuvq8dCKB2VnnaFfPsKkKaBBxF6U4.jpg?itok=1o-SKDa7)