Germany’s budget: increased investment and debt

After nine months of operating under a provisional financial plan, on 18 September the Bundestag adopted the federal budget for 2025. The delay was a consequence of the collapse of the SPD–Greens–FDP government in autumn 2024, triggered by a dispute over the form of the budget bill (see ‘Germany: the government coalition breaks up’). The early election in February and the new cabinet’s work on the draft budget significantly prolonged the adoption process.

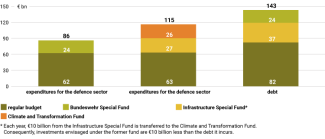

The budget amounts to €502.5 billion – €22 billion more than the previous year’s draft. This marks a departure from the traditional paradigm of fiscal restraint, as it nearly doubles the level of debt within the regular budget framework. Together with other off-budget funds, this is set to raise public debt by €143 billion. This significant borrowing is intended to stimulate economic growth by increasing public spending on infrastructure and the modernisation of the armed forces (see Chart 1). Total defence expenditure will amount to €86 billion. They are expected to rise in the coming years, reaching €153 billion by 2029.

The ambitious investment plans of the CDU/CSU–SPD government will result in a marked increase in this year’s debt, making it more difficult to consolidate the budget in future years. Despite the announced changes, the ruling coalition still lacks a coherent plan for reducing expenditure and reforming the pension and social welfare systems.

Commentary

- The first test of the effectiveness of the proposed economic reforms will be the implementation of investments under the 2025 budget. Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s (CDU) promises to improve the framework conditions for businesses have not translated into increased optimism in the economy. The failure to deliver on the pledge to reduce electricity prices for all entities has eroded voter confidence: only 22% express satisfaction with the government’s performance to date. Germany’s economy is facing the threat of deindustrialisation and the possible end of its export-based model. In the first half of the year, 12.2% more companies went bankrupt than in the corresponding period in 2024, while German cars are losing the competitiveness battle to Chinese brands. The authorities therefore intend to stimulate domestic demand and allocate €115 billion to investments before the end of the year, with only three months remaining. However, extensive reporting obligations, which regularly delay the disbursement of public funds, impede the implementation of this plan.

- The negative consequences of the expansionary fiscal policy aimed at stimulating economic growth will become evident in the years 2027–2029. The budget gap for that period is estimated at approximately €172 billion, raising concerns about the state of public finances. Vice Chancellor and Finance Minister Lars Klingbeil (SPD) intends to begin work on the 2027 budget as early as November this year (normally this would take place in spring 2026), with the aim of consolidating it. He is also calling for greater savings across ministries. The budget shortfall is driven, among other factors, by rising interest payments on accumulated debt and reduced tax revenues resulting from the business relief package adopted in July (see ‘The Bundestag adopts a tax relief package for business’). It may be possible to ease the pressure for fiscal consolidation by achieving faster economic growth (currently estimated at approximately 1% in 2026) and thereby increasing tax revenues. This is expected to be supported primarily by the off-budget Infrastructure Special Fund, whose resources are intended for investment. However, according to an analysis by the Bundesbank, a significant portion of these funds will in fact be used to fill gaps in the budget: in 2025, infrastructure spending is expected to increase by only €2.5 billion compared with the previous year.

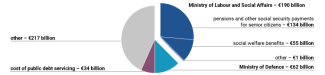

- The government lacks a clear strategy for curbing rising public spending. A particular burden on the state’s financial stability arises from the increasing costs of social insurance and welfare benefits, driven primarily by the ageing population (see Chart 2). The coalition partners have presented conflicting approaches to this problem. The CDU/CSU has announced an ‘autumn of reforms’, which is to involve changes to the social welfare system, beginning with a reduction of the citizen’s allowance (the annual cost of which is estimated at about €29.6 billion). The Social Democrats oppose such a move, preferring instead to raise taxes on the wealthiest as a source of additional revenue. There is also no coherent strategy for reforming the pension system or addressing the shortage of skilled labour. The government has avoided implementing the unpopular proposal of raising the retirement age and has instead introduced tax incentives for working pensioners. Paradoxically, the problem of early retirement remains unresolved: in 2024, only 40% of Germans continued working until they reached the statutory retirement age. To support the preparation of reforms, in September the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs established a Social Affairs Commission and a separate Pension Commission, which is scheduled to begin work in January 2026.

Chart 1. Structure of selected expenditure and debt growth in 2025, broken down by budgetary and extra-budgetary sources

Source: Bundestag, Federal Ministry of Finance.

Chart 2. Germany’s federal budget for 2025

Source: Bundestag, Federal Ministry of Finance.