New US peace plan: pressure on Kyiv on Moscow’s conditions

The 28-point peace plan that President Volodymyr Zelensky received in Kyiv from the US Secretary of the Army, Daniel Driscoll, on 20 November has reactivated diplomatic efforts aimed at ending the war in Ukraine. The document most likely corresponds to the version previously revealed by US media. Its key provisions are unacceptable to Kyiv and, at the same time, echo Russian demands. They have provoked outrage in Ukraine, as well as fears of coercion by the United States. The plan has also raised major reservations in Europe, and the E3 states (Germany, France, and the United Kingdom) have assumed responsibility for formulating a European response to the US initiative. On 23 November, a revised ‘European’ version of the document appeared in the media, containing language far more favourable to the security of Ukraine and of the continent as a whole. In parallel, talks on the US plan were held in Geneva between national security advisers from the E3 countries and delegations from the United States and Ukraine. According to their joint statement, the discussions were ‘highly productive’ and achieved meaningful progress, with the parties agreeing on a new, revised framework peace plan. Work will continue over the coming days. For Russia, the US document represents ‘one possible basis’ for dialogue, which in practice may signal its rejection unless the detailed terms arising from further debate impose additional restrictions on Ukraine’s sovereignty and security.

The US–Russian peace plan and manoeuvring in the White House

The plan presented to Kyiv was most likely drawn up during a meeting on 25 October in Miami between Vladimir Putin’s adviser Kirill Dmitriev, the US President’s envoy Steve Witkoff, and Donald Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner. Dmitriev’s visit to the United States took place against the backdrop of the US president’s growing impatience with Moscow’s unconstructive stance. After the Trump–Putin summit in Anchorage in August, Russia maintained maximalist demands towards Ukraine and refused a direct Putin–Zelensky meeting, which the US president had been pressing for. Contacts with the Russian side were subsequently taken over by the Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, who adopted a tougher line towards Moscow. After his talks failed, he cancelled another planned Trump–Putin summit in Budapest, and on 22 October Trump imposed sanctions on Russia’s two largest oil companies – Rosneft and Lukoil.

The plan now being put forward is a Russian-inspired attempt by Witkoff to re-enter the peace-negotiation process on terms favourable to the Kremlin, and it reflects power struggles between different factions within the White House. Witkoff and Kushner most likely did not involve Rubio in drafting the document. In conversations with US senators on 22 October, Rubio referred to it as a Russian plan, a statement from which he later backtracked, claiming instead that it was a US proposal informed by input from both the Russian and Ukrainian sides. J.D. Vance also appears to be playing an important role in the revived peace process. It was his protégé at the Pentagon – Secretary of the Army Driscoll – who presented the plan for ending the war in Kyiv, and the Vice President himself spoke with President Zelensky on 21 November. Vance’s greater involvement may be driven by a desire to counterbalance Rubio’s growing influence: Rubio has become the architect of US policy towards Venezuela and of increased pressure on Caracas. In this sense, the current activity may form part of a struggle for influence and positioning in the White House between two figures whom Trump has identified as potential Republican contenders for the presidency after his second term ends.

The return to the peace process initiated by Dmitriev, Witkoff, Kushner, and Vance has secured President Trump’s own approval. He has deemed the plan a framework and a basis for further talks. At the same time, he has increased pressure on Kyiv, giving it until 27 November to reach an agreement. Trump’s renewed willingness to pursue an end to the war may have been influenced by the success of the recent negotiations on Gaza, Russia’s more difficult position (owing to the new sanctions), Ukraine’s weakened standing (following the corruption scandal that undermined Zelensky), as well as domestic factors in the United States – Trump’s poor polling results and the reputational damage associated with the Epstein case.

Russia’s view of the plan: pathways to defeating Ukraine

The peace plan revealed by the media on 20 November aligns to a large extent (though not entirely) with Moscow’s publicly declared maximalist demands, which effectively amount to conditions for Ukraine’s surrender (see ‘Meeting in Istanbul: The Kremlin’s maximalist demands’). It is highly likely that the draft document was prepared on the basis of classified Russian memoranda, and that its key parameters were discussed during Witkoff’s meetings at the Kremlin. The leak of the plan’s contents to Western media was probably orchestrated by Dmitriev. Beyond fitting into Moscow’s broader tactics and attempting to exploit Kyiv’s weakened position, this step also served his personal agenda. Putin’s adviser seeks to highlight his pivotal role and effectiveness in dealings with the White House (he acts as Witkoff’s Kremlin ‘handler’ and has developed friendly personal ties with him), while sidelining the official channels of communication with Washington – the Foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov, and his deputy, Sergei Ryabkov.

The Kremlin’s official position on the new peace plan has undergone a shift. In response to the initial media leaks, Moscow sought to discredit its contents, claiming that it had not received any new proposals and continued to adhere to the ‘Anchorage arrangements’. This could be read as a signal that it expected further concessions. However, on 21 November Putin confirmed receipt of the plan from Washington (coinciding with Trump’s public endorsement of the document) and described it as ‘one possible basis’ for dialogue on peace. At the same time, he accused Kyiv of lacking the will to reach an agreement. Dmitriev, for his part, intensified his media activity, in which he mainly accused ‘European warmongers’ of attempting to torpedo the plan.

Ukraine: caught in the US–Russian grip

The key points of the document published in the media – recognising the whole of Donbas and Crimea as Russian, reducing the army to 600,000 troops, and renouncing ambitions of NATO membership – are unacceptable to Kyiv, as they entail acknowledging the loss of territory, including the humiliating withdrawal from areas of Donbas that Ukraine still controls and has heavily fortified, as well as relinquishing part of its sovereignty. Ukrainians are well aware that the proposed measures are intended to weaken them militarily and divide them politically so as to facilitate a future Russian invasion. On 21 November, Zelensky delivered an extraordinary address to the nation in which he acknowledged that Ukraine finds itself in one of the most difficult moments in its history and under immense pressure, yet simultaneously announced continued work on the plan, effectively rejecting it. The dramatic tone of the address nevertheless underscores the gravity of the situation. It also reflects the president’s concern that far-reaching concessions to Moscow could trigger anti-government protests, while signalling to Ukrainians that any eventual settlement may prove painful. His appeal for national unity was likewise intended to silence critics in the wake of the corruption scandal that precipitated the most serious domestic political crisis of his presidency (see ‘Operation Midas: the largest corruption scandal within Zelensky’s inner circle’).

The unequivocally negative and anti-US reaction of public opinion and the opposition strengthened Zelensky and the Ukrainian delegation in Geneva (although the appointment of the head of the Presidential Office, Andriy Yermak, as its chair was met with disapproval). Their main objective was to dilute the provisions unfavourable to Kyiv while accepting non-critical concessions and reinforcing or clarifying elements that could benefit the country (above all, US security guarantees). The Ukrainian negotiators sought to persuade the Americans that their plan would not be accepted by Russia, which, since the beginning of the war, has obstructed all efforts to achieve a ceasefire – let alone peace – because none of these initiatives has envisaged fulfilment of Moscow’s primary demand: full political control over Ukraine. During the talks, Zelensky indicated that the US side was receptive to Ukrainian arguments. Moreover, the wording of the joint statement that ‘any future agreement must fully uphold Ukraine’s sovereignty and deliver a sustainable and just peace’ may suggest that the revised arrangements are more favourable to Kyiv. Ukraine considers its European partners to be key allies capable of influencing Washington’s position. It believes that the continent’s security depends on the conditions under which the war ends, allowing one to assume that European and Ukrainian demands are largely convergent.

Europe: efforts to secure a seat at the table

The US-proposed document is largely unacceptable not only to Kyiv but also to Europe, as it contains provisions concerning the security of the entire continent that were not agreed with European allies. A peace in Ukraine established on the basis of the original US–Russian plan, which in effect recognises a Russian victory, could enable Moscow to rebuild its military potential and subsequently resume aggression both against its neighbour and – in the longer term – against Europe. The plan includes clauses on dialogue between Russia and NATO ‘mediated by the United States’, which could provide grounds for further Russian demands aimed at reducing Allied presence on NATO’s eastern flank under the pretext of ‘creating conditions for de-escalation’.

The document compels NATO to adopt formal commitments precluding Ukraine’s accession, which runs counter to the Alliance’s established policy. It also prohibits any NATO military involvement in the country, which Moscow would view as incompatible with European proposals for a peacekeeping mission designed to enhance Kyiv’s security after the conflict. The clause regarding the stationing of ‘European fighter jets’ in Poland is sufficiently vague to allow for multiple interpretations: it could be understood either as a form of reassurance for Ukraine provided by European states in the event of renewed Russian aggression, or as a restriction limiting the Allied presence in Poland to air-force contingents from European countries alone.

On the European side, coordination of the response to US actions has this time been undertaken by the E3 countries: France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. In consultation with other EU and G7 members, they issued a statement indicating that the US plan requires further work to ensure both lasting peace in Ukraine and consensus among NATO and EU states on its implementation. On 23 November, the national security advisers of the E3 states met with Ukrainian and US delegations for talks in Geneva. In addition, the press (Reuters) obtained a leaked version of the plan revised by E3 representatives, which amends the most contentious provisions of the US document. Visits by European leaders to Washington, similar to those previously aimed at persuading President Trump of the European (and Ukrainian) position, cannot be ruled out.

Outlook

Reaching an agreement acceptable to both Ukraine and Russia is impossible at this stage of the war. Although Ukrainians are exhausted by hostile air attacks and by interruptions to electricity and heating supplies, for most of them acquiescing to conditions that would in practice amount to submission to Moscow’s dictate remains unacceptable. The corruption scandal has significantly undermined Zelensky’s domestic credibility, but in foreign policy it will only harden his position, all the more so as his objectives continue to enjoy broad public support.

Russia’s tactics are geared towards implementing one of two scenarios. Under the first, the objective would be Ukraine’s political capitulation, ‘co-operation’ with the United States, and preparations for a renewed offensive. The Kremlin would enter talks on the basis of the US proposal, seeking to tighten the peace plan’s detailed provisions in ways that would further curtail Ukraine’s sovereignty and security. Once convinced it could extract no more, it would agree to a ‘peace’ (in effect, a temporary pause), expecting Washington to compel Kyiv to accept it. Moscow’s intention is that this would trigger political destabilisation in Ukraine, Zelensky’s departure from office, and a crisis in US–European relations. Dismantling the sanctions regime would enable Russia to rebuild its armed forces rapidly and could allow the Kremlin to resume its aggression against Ukraine and/or undertake military action against states on NATO’s north-eastern flank.

In the second scenario, the aim would be Trump’s abandonment of Kyiv and a military victory over Ukraine. Effectively, after unsuccessful attempts to dilute them, the plan’s rigid conditions would lead Kyiv (with Europe’s backing) to reject it. Moscow would then blame Ukraine and Europe for the collapse of the peace process and persuade the US president to withdraw all military and intelligence support for Kyiv (and perhaps even to prohibit the sale of US-made weapons to it). This would cause a grave deterioration in Ukraine’s military position, enabling Russia to make gains on the battlefield and, in the longer term, to impose draconian terms of surrender on Kyiv. Alongside this, efforts to settle the conflict in Ukraine would be decoupled from the process of normalising Russian–US relations (as the Kremlin has openly stated). Despite the absence of peace, Trump would announce the lifting of sanctions on Russia (triggering divisions within the EU that would lead to the collapse of Europe’s sanctions regime) and endorse business co-operation with Moscow, thereby strengthening it.

If, however, Kyiv and the European states succeed in persuading Washington to significantly soften the proposed peace terms, Moscow will refuse to accept them, will attempt to blame the Ukrainian and European sides for the collapse of the process, and then move to bring about the second of the scenarios discussed above

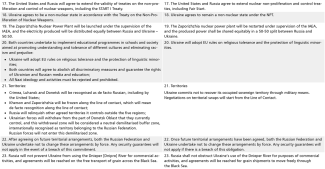

Appendix. Comparison of the initial US peace plan and its revised European version

Source: Reuters.