Russia’s 2026 budget: mounting financial challenges and economic stagnation

On 28 November, Vladimir Putin signed the Russian Federation’s 2026 budget law and approved the overall parameters of the budgets for 2027–28, after the document had passed swiftly through parliament. In drafting next year’s budget, the government relied on optimistic assumptions, particularly with regard to oil export prices, the pace of economic growth, and tax collection rates. Despite this, the budget will run a deficit in 2026. Government spending will increase only in line with official inflation, which means that it could in fact decline in real terms. Notably, for the first time since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin has announced a reduction in funding for national defence. Nevertheless, as the war remains its top priority, the government could allocate additional resources to it should circumstances require. Shrinking government reserves, low oil prices, and adverse economic trends no longer allow for the sustained rapid growth in public spending that has been the main driver of Russia’s macroeconomic indicators since the start of its invasion of Ukraine.

Russia has reached the limits of its financial capacity: as spending continues to rise, the economy is coming under increasing strain. The draining of capital from both households and businesses is further dampening domestic economic activity, thereby shrinking the tax base. At the same time, issuing government bonds on the domestic market has become extremely costly and inflationary. Even this year, the government is likely to face serious difficulties in financing the growing budget deficit. Unless international conditions improve, particularly through a rise in oil prices or a change in Western sanctions policy, closing the gap in the state budget will become an even greater challenge next year, especially as the deficit may prove to be significantly higher than planned.

An economy in stagnation

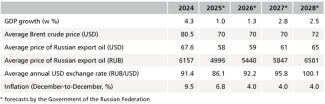

In drafting the 2026 budget law, the Russian government sharply revised its previous macroeconomic assumptions for both 2025 and 2026.[1] These updated projections take into account the economic slowdown observed since mid-2024 and the decline in prices for Russian oil exports. The Russian economy has effectively stagnated and is likely to remain in this condition in the coming years.

At present, official forecasts from Moscow and international institutions do not anticipate a recession in Russia. However, projections by the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development are less optimistic than those of the Russian government, forecasting lower GDP growth in 2026 – just 1.1% and 0.7%, respectively. Given the high volatility of developments within Russia, and particularly in its external environment – including fluctuations in oil prices and Western sanctions policy – macroeconomic forecasts for the country are frequently revised.

Projections for global oil prices are particularly unfavourable for Russia’s budget outlook. Most international institutions expect the oversupply of crude to deepen, driving prices well below $60 per barrel. Russian forecasts are more optimistic, assuming that the average annual price of Russian export oil (trading at a discount) will be slightly higher in 2026 than in the current year. In November, after US sanctions targeting Rosneft and Lukoil came into force, it was selling at around $50 per barrel, compared with the $60 baseline price set in the budget. In 2026, the Kremlin will seek to offset the negative impact of low oil prices by weakening the rouble. To this end, the central bank plans to loosen its monetary policy, a move enabled by declining inflation.

Table. Government assumptions for Russia’s macroeconomic indicators, 2025–2028, and results for 2024

Source: Rosstat, Government of the Russian Federation.

Questionably optimistic assumptions on budget revenues

According to government plans, Russia’s nominal budget revenues are set to increase by more than 10% in 2026, reaching 40.3 trillion roubles (approximately $480 billion, based on the projected exchange rate). As a share of GDP, revenues are expected to remain at 17.1% – the same level as in the current year – although this would still represent a decline of nearly one percentage point compared with 2024.

The government is forecasting a particularly sharp rise in non-oil and gas revenues: 12.5% year-on-year, amounting to 3.5 trillion roubles, equivalent to $37.9 billion at the exchange rate assumed for 2026. This increase is expected to stem primarily from higher fiscal burdens. From 2026, the VAT rate on goods and services will rise by 2 percentage points to 22%, while most tax exemptions for small and medium-sized enterprises will be abolished, effectively bringing them within the VAT regime. Preferential VAT rates of 0% and 10% will continue to apply to goods deemed socially important, such as food, medicines, and children’s products.

According to estimates, the VAT increase will generate an additional 1.2 trillion roubles (approximately $13 billion) in budget revenues in 2026. The government has also planned further increases in import duties, particularly on motor vehicles. Together with a further rise in the recycling fee on imported cars, the government anticipates additional revenues of 500 billion roubles (approximately $5.5 billion). In addition, a new levy on imported electronics, including computers and smartphones, is to be introduced in September 2026. However, it is not expected to become a significant revenue source in the following year, contributing only around 20 billion roubles (approximately $217 million).

The projected sharp rise in non-oil and gas revenues raises serious concerns. Further tax hikes, particularly the VAT increase, may fail to boost revenue as intended and instead exacerbate negative economic trends, including a continued decline in demand and corporate income, thereby further eroding the tax base. Under such conditions, achieving the government’s projected GDP growth of 1.3% may prove impossible, resulting in lower-than-planned budget revenues.

Even in 2025, the continued increase in fiscal burdens failed to generate the expected inflow of additional revenues and instead contributed to a deterioration in economic conditions. A rise in the corporate profit tax slowed investment, as high interest rates and limited access to international financial markets forced companies to rely primarily on their own resources. In addition, a sharp increase in the recycling fee on vehicles drove down demand and imports, causing a decline in domestic production and significantly reducing budget revenues from imports, particularly through customs duties and indirect taxes.

The Kremlin may also seek to bolster the budget through higher prices by exerting pressure on the central bank to ease its currently restrictive monetary policy. The Central Bank of Russia’s revision of its inflation forecast for 2026 from 4% to 4–5% may signal such a policy shift.

Oil and gas revenues are expected to rise only marginally in 2026, mainly due to a weaker rouble. As a result of persistently low oil prices, their share of total budget revenues is projected to fall to 22%, roughly the same as in 2025 and down sharply from 42% in 2022. At the same time, with Russia cut off from international financial markets, exports have become its main source of foreign currency.

Pessimistic forecasts for global oil prices next year, combined with a slowdown in domestic business activity, pose a serious risk to the implementation of Russia’s planned budget.

Spending growth stalls, but the war remains a priority

Current revenues do not support further rapid growth in public spending. In addition, the government has been forced to respond to low oil prices. To this end, it has decided to lower the so-called baseline oil price set in the budget from $60 per barrel in 2025 to $59 in 2026; however, this level remains significantly higher than before the invasion (in 2021, the price stood at around $45). This adjustment has had a negative impact on budget expenditure. Under Russian law, the government may use oil and gas revenues for current spending only up to the baseline price. Revenues generated above that level are transferred to the National Welfare Fund (NWF) as reserve assets. If the market price remains below the baseline, the budget shortfall is covered using funds from the NWF – as is the case in 2025.

As a result, budget expenditure in 2026 is set to increase by just 4% year-on-year. If inflation exceeds the government’s forecast, spending could fall in real terms, as it did in 2025. By contrast, in 2024 budget expenditure surged by 24%. In 2026, it is projected to reach 44.1 trillion roubles (approximately $438 billion, based on the exchange rate assumed for next year), equivalent to 18.7% of GDP – down from 19.5% in 2025 and 20% in 2024. Under current political and economic constraints, the Russian government has effectively reached the limits of its fiscal capacity. Any further increase in spending would place increasing pressure on the economy.

According to the budget law, funding for national defence will decrease by 4% year-on-year in 2026, meaning that, in real terms, the decline could be considerably deeper. This represents an exceptional development, as defence spending has been the fastest-growing budgetary category since the start of the invasion. However, the security and defence sector will receive additional resources through an increase of more than 11% year-on-year in allocations for internal security. These funds are used to support war-related operations and to sustain the system of repression and control over the population. Taken together, these two categories will account for 38% of total nominal budget expenditure. Spending on the national economy is also set to rise next year. This includes funding for research and development, as well as programmes aimed at helping the economy adapt to sanctions, implemented across industry, transport, and logistics. A significant share of these funds is channelled to defence companies. It is also important to note that around 25% of budget expenditure remains classified, with over 80% of that amount allocated to military purposes. This significantly increases the opacity of Russia’s budgetary system.

The increase in funding for the military and the repressive apparatus comes at the expense of the general public. Combined spending on social policy, education, and healthcare will account for just under 24.4% of the total budget – 5 percentage points less than in 2024 and a full one-third less than before the invasion. The nominal increase in this expenditure stems primarily from the Kremlin’s constitutional obligation to index social benefits and pensions on an annual basis. Consequently, the government has a vested interest in keeping official inflation figures low. Nevertheless, it has abandoned a number of support programmes: for example, in 2024 it terminated large-scale subsidised mortgage lending. It has also regularly raised charges for public services, including transport, housing and utilities, as well as the supply of gas, electricity, and water. Importantly, the government is not concealing its priorities from the public. When announcing the planned VAT hike for 2026, Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov stated openly that the additional revenue would be channelled to the security and defence sector.

Another area in which the government has curtailed funding is transfers to the regions, despite the fact that the Kremlin has burdened them with a significant share of the costs of providing social support and mobilising recruits for the war. In 2026, regional budgets will receive a total of 3.6 trillion roubles (equivalent to $39 billion at the exchange rate assumed for the following year) from the federal government, roughly the same amount as in 2021 (3.5 trillion roubles). In real terms, this represents a substantial reduction. The regions are increasingly struggling to meet their obligations, particularly as the growth of their own revenues has slowed, reflecting the broader economic slowdown. Their primary source of income is personal income tax. As of September 2025, more than 66% of all regions (out of 89, including six in the occupied Ukrainian territories) were running a budget deficit.

In recent years, debt servicing has become one of the fastest-growing items in the Russian budget. In 2026, the government will need to allocate nearly 9% of public funds to this purpose. In the coming years, this share is expected to increase further, driven by budget deficits that have continued to grow since the start of the invasion of Ukraine and the need to finance them.

It is also important to note that actual budget execution, as past experience shows, often diverges significantly from government projections. Consequently, the announced reduction in national defence spending may not materialise should developments on the battlefield demand otherwise. The war remains the Kremlin’s overriding priority, and it can still mobilise additional resources to finance it, notably at the expense of other sectors. However, its fiscal room for manoeuvre is clearly narrowing.

Mounting challenges in financing the budget deficit

Despite a further increase in the tax burden, next year’s budget still projects a deficit, with a funding shortfall equivalent to nearly 9% of planned expenditure. This gap is to be covered primarily through increased borrowing and further bond issuance. Although Russia’s public debt remains relatively low (it is projected to reach 18.6% of GDP in 2026), the government will need to allocate nearly 1.7% of GDP to service it.

With no access to inexpensive foreign capital, the government has been forced to borrow on the domestic market, where interest rates remain high – currently at 16.5%. As a result, this form of financing is becoming increasingly unattractive. Most of the funds raised in this way are used to service and repay existing debt. Moreover, continued government borrowing is exacerbating inflationary pressure.

At the same time, the Kremlin is seeking to protect the shrinking reserves held in the NWF, which partly explains its decision to lower the baseline oil price set in the budget. The Fund’s liquid assets (those available for government use) are currently smaller than the budget deficit planned for 2025. NWF funds provide the government with a degree of flexibility, but they have also been used to finance infrastructure projects and support key state-owned corporations, including Rostec, which holds a dominant position in the defence sector. As a result, the share of liquid assets in the NWF has been falling. These assets have been invested primarily in gold and Chinese yuan, meaning that their value in roubles is highly sensitive to fluctuations in the rouble exchange rate and gold prices.

In the initial period following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, oil prices remained above the baseline level set in the budget, allowing the NWF to be replenished regularly with excess oil and gas revenues. However, since early 2025, oil prices have remained below that threshold, preventing any replenishment of the Fund’s assets in 2026. The NWF will continue to generate returns from its existing investments, particularly those in state-owned banks such as Sberbank and VTB, although financial operations involving the Fund’s accounts are recorded with a significant delay. According to government estimates, by the end of this year the Fund will still hold 3.8 trillion roubles in liquid assets (approximately $49 billion at the current exchange rate), but this amount falls to 2.9 trillion roubles ($37 billion) once planned investments in infrastructure projects are taken into account. These reserves will not provide the government with significant fiscal comfort in 2026 and may prove insufficient to cover a potential shortfall in oil and gas revenues should global oil prices fall sharply.

A budget in need of sanctions relief

The 2026 budget appears overly optimistic, as its implementation may be undermined by a number of factors, including falling oil prices and a further economic slowdown. Consequently, the document is likely to be revised during the year in response to evolving economic conditions and shifting government priorities. There is little doubt that financing the deficit will pose a major challenge for the Kremlin, adding to the rapidly expanding list of problems it faces.

In Russia’s current economic situation, any easing of Western sanctions – particularly those imposed by the United States – would provide the Kremlin with significant relief and help it avoid serious financial difficulties. This explains why demands to lift these restrictions has featured so prominently in the ongoing negotiations between Moscow and Washington. From the perspective of public finances, a complete rollback of US sanctions – which remains one of Putin’s maximalist demands – is not necessary. For the Russian economy, even a decision by the US to ease the enforcement of existing restrictions would offer significant benefits.

If Washington fails to curb the circumvention of sanctions imposed on Russia’s major energy companies, including Rosneft and Lukoil, the Kremlin will be able to sustain its oil exports and significantly reduce the discount on its crude, thereby boosting budget revenues. Indeed, signs of erosion in the financial sanctions regime imposed by the Biden administration have been evident since late January 2025. By choosing not to impose secondary sanctions on entities violating these measures, the US has enabled Russia to establish new, effective channels for cross-border transactions and to sharply reduce associated banking fees – from around 10% in late 2024 to as low as 1%.

[1] For further details, see I. Wiśniewska, F. Rudnik, ‘Russia’s stagnating economy’, OSW, 21 October 2025, osw.waw.pl.