Methodical elimination. Efforts to dismantle the local government system in Russia

The Putin regime has spent over two decades gradually stripping local governments of their autonomy as part of a consistent process of state centralisation. The effective dismantling of the local government system is now nearing completion, pursued under the pretext of improving its functionality. These changes, which undermine the interests of the local population as well as those of local and regional elites, have triggered grassroots resistance. Nevertheless, the Kremlin is unlikely to alter its current course, aiming instead for further consolidation of power. The elimination of local self-governance gives the federal centre significant control over local authorities, where limited political pluralism had previously persisted. At the same time, however, it creates a range of challenges for the Putin regime, which could prove dangerous in the future.

The gradual elimination of the local government system

For a decade following the collapse of the USSR – where a local government system had been virtually non-existent until the very end, with local councils serving as a token substitute, lacking property and effectively dependent on the Communist Party – local governments in Russia developed through a process of experimentation. They took on various forms, often shaped by regional specificities. Amid economic crisis and a weakened federal centre, local authorities in municipalities (territorial local government units), which were constitutionally distinct from state authorities (federal and regional), enjoyed considerable political autonomy and faced little pressure from Moscow. They were more dependent on regional governments, which at the time also exercised significant independence from the federal centre.

The process of stripping local governments of their autonomy began shortly after Vladimir Putin came to power in 2000 and unfolded in parallel with the Kremlin’s new policy of centralisation.[1] A reform introduced in 2003 under the pretext of delineating jurisdictions and competences between state and local authorities effectively unified the organisational structure of local government, in breach of the Russian Constitution. A diverse system of higher- and lower-level municipalities – where the latter formed part of the former – was replaced by urban districts and municipal districts (raiony) encompassing both rural and urban settlements (poseleniya).

To weaken the position of municipal leaders, the government prohibited them (with the exception of localities with fewer than one thousand residents) from simultaneously holding the posts of head of local administration and chair of the representative body. The official justification was a desire to limit the dominance of the local executive over the legislature, which allegedly created a wide range of opportunities for corruption.[2]

As a result, the institution of the so-called city manager was established – a contracted administrator of local government appointed through a competitive process – as an alternative to an elected mayor chosen by popular vote. Appointing such an official, who lacks a democratic mandate, not only created a conflict of interest (as the head of the municipality, chosen from among local deputies, was required to transfer most of their powers to the appointed administrator) but also diluted accountability to residents and limited public influence over local politics.

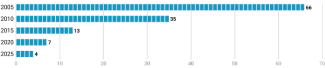

By 2014, city managers were in charge of 58 regional capitals, and the number of administrative centres where mayors were directly elected had fallen from 75 to 19 (out of 83). In 2015, new regulations were introduced to give the system a semblance of electoral legitimacy – after completing the competitive selection process, each candidate must be confirmed by a vote of local deputies. Today, direct mayoral elections survive only in Yakutsk (Republic of Sakha), Khabarovsk (Khabarovsk Krai), Anadyr (Chukotka Autonomous Okrug), and Abakan (Khakassia).

Chart 1. The number of regional capitals with direct mayoral elections

Source: author’s own analysis.

Alongside structural changes, the local government system in Russia – though formally separate from state authorities – has in practice come under their control. Regional authorities, which effectively function as territorial extensions of the Kremlin[3], were granted the right to determine how local government bodies are elected within their jurisdictions, as well as to appoint half the members of the selection committees responsible for choosing local administrators. In 2024, governors were given the power to issue warnings and reprimands to municipal heads and heads of local administrations, and to dismiss them or request their removal through local legislative bodies.

The 2020 constitutional amendment, which cemented Russia’s super-presidential system and further centralised power[4], served as a catalyst for the final dismantling of local government autonomy. A draft law that fundamentally restructured – and in practice dismantled – the system was submitted in December 2021. Owing to the domestic political context – the invasion of Ukraine, the 2024 presidential election, and grassroots resistance – Putin did not sign the legislation until March 2025.[5]

One of the main objectives of the reform was to abolish the two-tier municipal system by merging lower-level units into larger entities. For example, in Krasnoyarsk Krai, there were 472 units prior to the changes: 17 urban circuits (okruga), 12 municipal districts, 32 municipal districts, 389 rural settlements, and 22 urban settlements. Following the reform, only 39 units will remain – six urban circuits and 33 municipal circuits.

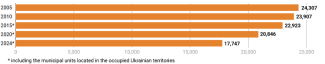

This top-down mandate was intended to accelerate transformations already underway. By the time the law was adopted, 20 regions – under pressure from the Kremlin – had already implemented the changes, including the occupied territories of Ukraine (the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics and, from 2022, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts). This trend was reflected in the steadily declining number of municipal units.

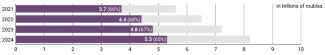

Chart 2. Number of municipal units in Russia

Source: author’s own analysis.

As a result of the abolition of the lower tier of municipal government, up to 99% of all elected positions in the country could disappear. The new legislation sparked opposition from regional and local elites (see below), prompting the Kremlin to make limited concessions. Regional authorities were granted the option to decide on the structure of local government. In 25 federal subjects, only partial reform was announced, while a further 17 chose to retain the previous model. However, it remains unclear whether the two-tier structure can survive beyond 2035, when the ten-year transitional period ends.[6] It cannot be ruled out that Moscow will pressure regions to implement the changes even earlier.

The reform affected not only the structure of local government but also the core principles of its internal organisation. Under the new system, in those locations where direct elections no longer take place, municipal heads are selected not from a pool of applicants who have passed preliminary screening, but from a shortlist presented by the governor. All regional capitals are now required to adopt this system, meaning the last four administrative centres will soon cease to elect their leaders directly.

Candidates may be nominated by political parties and regional representative bodies, but also by federal-level institutions such as State Duma deputies, the Civic Chamber of the Russian Federation, or the All-Russian Association for the Development of Local Self-Government, which brings together local associations. This creates a risk that local posts will be filled by officials with no connection to local politics – a practice previously used mainly at the regional level.[7]

The Kremlin is already preparing new staff. In 2023, it launched the so-called ‘school for mayors’ (modelled on the ‘school for governors’, in operation since 2017) – a programme run by the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, coordinated by Sergei Kiriyenko, the influential First Deputy Chief of the Presidential Administration. Four cohorts have completed the training, totalling 321 individuals who previously held senior local and regional posts. The rotation of such ‘professional managers’ between municipalities will enable Moscow to avoid situations in which heads of local governments become too closely embedded within local business and administrative elites.

Total control

The reform of the local government system is officially justified by the need to improve its efficiency,[8] and financial sustainability. In reality, however, it serves the Kremlin’s political agenda of consolidating power. The legal subordination of local authorities to regional administrations – effectively placing them under close supervision from Moscow – accords with the centralising logic of the Putin regime.

The de facto dismantling of the local government system enables the effective demobilisation of the urban electorate, which has traditionally formed the core of opposition movements. It also significantly weakens the potential for grassroots protest and reduces the likelihood of support from local elites. Parallel measures, such as the digitalisation of administration and the widespread adoption of electronic voting, further strengthen the Kremlin’s control over the electoral process at the local level and reduce the federal centre’s dependence on local officials.[9]

Tightened control over local government benefits Putin’s ruling party, United Russia, while simultaneously curbing the influence of the so-called systemic opposition. At the municipal level, this opposition – particularly the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF)[10] – had previously been able to mount genuine resistance to the authorities, alongside independent activists. One consequence of merging municipal units is the ability to offset dissenting sentiment in urban areas with votes from smaller localities, whose residents tend to be more loyal to Moscow.

United Russia’s dominance in local government will also enable the Kremlin to manipulate gubernatorial elections more effectively through the so-called ‘municipal filter’ system.[11] Additionally, it will facilitate the use of so-called ‘administrative resources’ – such as the votes of public-sector employees, civil servants, and workers from large enterprises – to secure desired outcomes in elections to regional parliaments, the State Duma, and the presidency.

In recent years, Moscow has emphasised the need to increase the financial independence of local governments.[12] However, the changes appear to be moving in the opposite direction.[13] Municipalities remain heavily dependent on interbudgetary transfers – both regional and federal – including subventions (to support the implementation of specific tasks delegated by higher-level authorities), as well as subsidies and budgetary grants. Without these, they would be unable to cover even their routine operational expenses.

Chart 3. Share of interbudgetary transfers in municipal budget revenues

Source: Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation.

The reform introduces virtually no measures to strengthen the financial base of municipal budgets. At the same time, the share of state loans in local government debt is increasing – rising from 61% in January 2024 to 63% in January 2025 – at the expense of commercial loans.[14] This trend further deepens the dependence of local authorities on the federal centre.

In fact, the changes may further exacerbate their financial difficulties. While 18 exclusive competences have been assigned to local governments, regional authorities may delegate a similar number without being obliged to provide corresponding funding. Moreover, governors are authorised to dismiss municipal heads who fail to fulfil the delegated tasks, giving them yet another instrument of oversight and pressure.

The expansion of control over local government also requires the Kremlin to become more directly involved in hands-on management at the local level. This shift entails several potential challenges.

By eliminating the lower tier of municipal government, the centre is depriving itself of institutions that operated closest to the public. As a result, the regime’s capacity to detect social tensions early and respond swiftly to outbreaks of discontent may be weakened. Local government structures have also served as a useful façade for Moscow’s increasingly authoritarian policies, providing citizens with the illusion of agency at the local level. Moreover, the authorities have often shifted blame for socio-economic protests onto lower-level officials, portraying themselves as neutral arbiters. The recent organisational changes will make it more difficult to apply this mechanism in the future.

As the system of local self-government has been systematically dismantled, its prestige and appeal have steadily declined. This is especially true of the position of mayors in major cities, which once carried extensive powers and access to financial resources. Participation in local legislative bodies is generally unpaid – only the chairpersons, their deputies, and committee heads receive a salary – and the benefits and influence associated with holding a deputy’s mandate have diminished over time.

Holding office can also pose a personal risk. Across Russia, both current and former local officials are regularly arrested on corruption charges – the validity of which is often impossible to verify – and they remain largely defenceless against the security services. Even high-profile figures are not immune. In June 2025, the mayor of Krasnoyarsk, Vladislav Loginov – a United Russia politician and former member of the State Council of the Russian Federation – was detained.

As a result, fewer candidates are standing in local elections, and experienced managers are becoming increasingly reluctant to seek municipal posts.[15] A telling example is the city of Novokuybyshevsk in Samara Oblast, with a population of 100,000, which remained without a mayor for over a year;[16] this is by no means an isolated case.

In the longer term, this situation may trigger a serious personnel crisis, which can only be partially mitigated by drawing on graduates of the so-called ‘school for mayors’. In April 2025, Putin called for greater involvement of veterans of the invasion of Ukraine in local government work,and the authorities are actively seeking to integrate them into the system.[17]

Grassroots resistance

The abolition of the lower municipal level removes nearly all elected positions in the country. The more prominent of these roles were often held by individuals linked to regional elites. As a result, the changes have adversely affected the interests of the local bureaucratic apparatus and its patrons.

The reform has provoked particular discontent in the ethnic republics, where – despite the Kremlin’s centralising policies – clan-based structures (the fusion of political power with bureaucratic and business elites) remain particularly entrenched. Influential leaders of Tatarstan and Bashkortostan – Rustam Minnikhanov and Radiy Khabirov, respectively – have publicly voiced their opposition to the reform. Vyacheslav Volodin, Speaker of the State Duma, expressed support for compromise amendments to the legislation.

Grassroots resistance from regional elites proved relatively effective: the legislative process was significantly delayed, and Moscow, faced with criticism, softened the original provisions of the bill. It introduced certain concessions, including a transitional period until 2035 and the option for regions to retain the two-tier model of local government. However, the long-term viability of these concessions remains highly uncertain. The trajectory of Putin’s centralising policy indicates that the federal centre will exert increasing pressure on those federal subjects that have retained the old system to adopt the new framework.

Map. Model of local government organisation in Russia’s regions

Source: author’s own analysis.

The reforms have also met with public resistance. Notably, it was not residents of major cities who initiated the protests, but rather those from peripheral areas, who stand to be most affected by the dismantling of the local government system. In some cases, they were supported by local officials and deputies, particularly from the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF).

This resistance is set against the backdrop of the rapid decline of smaller urban centres, including those located in otherwise developed regions. There are currently 1,120 towns and cities in Russia, 70% of which are categorised as small or medium-sized. In the near future, as many as 129 of them – home to nearly 3.5 million people – could effectively disappear. Over the past decade, the population of these towns has declined by more than 300,000.[18] The causes of this decline include reliance on industrial sectors with limited growth prospects (such as the coal sector), the outflow of young people to major urban centres, ageing utility infrastructure,[19] underdeveloped transport networks, inadequate local education and healthcare systems,[20] and a lack of sufficient investment.

At least some of these issues stem from the extremely limited autonomy of local governments and the concentration of economic and political life in regional capitals. As part of the so-called optimisation process, public facilities – such as clinics, schools, and post offices – are being closed in towns and settlements deemed ‘non-viable’, further deepening the socio-economic marginalisation of local populations.

The largest protests took place in regions geographically distant from the capital, including the Altai Republic and Krasnoyarsk Krai. In late June 2025, several thousand people joined a protest rally in Gorno-Altaisk, demanding the resignation of Kremlin-appointed governor Andrei Turchak (former secretary of United Russia’s General Council). Residents also blocked roads, and the authorities’ decision was challenged in the republic’s Supreme Court, although the complaint was dismissed. Smaller demonstrations in Krasnoyarsk Krai in May 2025 were joined by local officials and veterans of the invasion of Ukraine.

These protests must also be understood within their local context. The Altai Republic, which relies on cattle farming and tourism, has a population of just 210,000 – around 70% of whom live in rural areas. It now faces the expansion of large external businesses, including Russia’s largest bank, Sberbank. The reforms will make it easier for such actors to purchase land, fuelling local resentment. Resistance is also being fuelled by recurring proposals to merge the Republic with the neighbouring Altai Krai – plans that resurface every few years and continue to provoke strong opposition.

In the case of Krasnoyarsk Krai, geography has proved to be a decisive factor.[21] The region spans more than 2.3 million square kilometres, yet is home to fewer than 3 million people. Distances between settlements are vast, and transport connections are limited. Local identity also plays a significant role. Discontent among residents of Yeniseysk – known as the ‘father of Siberian cities’ (founded in 1619) – was sparked by the prospect of incorporation into an urban circuit centred on Lesosibirsk, a town established as recently as the 1970s.

The authorities responded to the protests by accelerating work on the local government reform, pushing the changes secretly, and resorting to targeted repression. The reforms in regions that opposed them were adopted in their original form, with only occasional and minor concessions.[22] In contrast to resistance from political elites, public protests thus proved ineffective.

A future without local self-government

Resistance to the reform highlights the unpopularity of the Kremlin’s centralising policy – not only among regional and local elites but also among ordinary citizens – and underscores Russians’ attachment to local self-government, even one with severely limited powers.

Moscow is likely to continue pursuing the elimination of the two-tier local government system across all regions. Cases of elite resistance following the adoption of the law suggest that further opposition will be ineffective. For instance, Valentin Konovalov, the CPRF-affiliated governor of Khakassia, vetoed legislation implementing the single-tier model in the Republic, but he faces a regional parliament dominated by United Russia. Similarly, a court in Krasnoyarsk dismissed a petition by district legislators seeking to halt the reform. In the Altai Republic, deputies in half the districts refused to amend local statutes, but this is unlikely to stop the changes from going ahead.

Demands to restore direct mayoral elections in regional capitals also appear doomed to fail. However, the issue remains popular in large cities, making it a useful campaign theme for systemic opposition parties. In the Irkutsk gubernatorial race, for example, CPRF candidate Sergei Levchenko ran on a platform that included reinstating direct mayoral elections.[23]

The potential for protest at the local level still exists, and Russians have shown a willingness to demonstrate over issues that directly affect them.[24] However, due to the lack of coordination between individual protests and limited support from opposition parties, such outbreaks of discontent do not currently pose a serious political threat to the Kremlin. Nonetheless, the deteriorating living conditions – combined with the absence of a safety valve in the form of local government – could exacerbate public attitudes towards the central authorities, which are likely to be increasingly seen as directly responsible for problems affecting daily life at the local level.

The dismantling of the lower municipal tier is likely to deliver the final blow to peripheral regions. The system of local government will become even more centralised and, as a result, less responsive to the needs of small towns and rural areas. These communities will suffer as municipal functions – administration, public services, financial resources, and more – are transferred to local centres, leaving behind only a handful of field-level officials. This will accelerate the depopulation of the provinces. Local political and civic activism, which until now has largely been concentrated within municipal structures, is likely to disappear almost entirely outside of larger urban centres. Local personnel, stripped of influence and purpose, will most likely withdraw from public life.

[1] J. Rogoża, ‘Federation without federalism. Relations between Moscow and the regions’, OSW, Warsaw 2014, osw.waw.pl.

[2] Н.А. Кандрина, ‘Модели организации муниципального управления, глава муниципального образования и сити-менеджер’, „Вестник Алтайской академии экономики и права” 2011, no. 3(21), sciup.org.

[3] M. Bartosiewicz, ‘A tactical pause. The Kremlin's regional policy in the shadow of the war’, OSW Commentary, no. 543, 6 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[4] M. Domańska, ‘"Everlasting Putin" and the reform of the Russian Constitution’, OSW Commentary, no. 322, 13 March 2020, osw.waw.pl.

[5] Федеральный закон от 20.03.2025 № 33-ФЗ "Об общих принципах организации местного самоуправления в единой системе публичной власти", Официальное опубликование правовых актов, 20 March 2025, publication.pravo.gov.ru.

[6] Е. Мухаметшина, ‘Третье чтение законопроекта о местном самоуправлении пытались остановить’, Ведомости, 6 March 2025, vedomosti.ru.

[7] А. Pertsev, ‘Russia's Local Government Reform Will Destroy a Rare Channel for Letting Off Steam’, Carnegie Politika, 11 November 2024, carnegieendowment.org.

[8] А. Прах, ‘Секретарь генсовета «Единой России» поддержал отмену прямых выборов мэров’, Коммерсантъ, 15 June 2025, kommersant.ru.

[9] A. Toth-Czifra, ‘The municipal reform and political power in Russia’, Riddle, 3 April 2025, ridl.io.

[10] А. Тихонов, ‘Эксперты разглядели в реформе МСУ угрозу некоторым партиям на местном уровне’, Ведомости, 11 August 2025, vedomosti.ru.

[11] A candidate wishing to stand for the position of governor must collect signatures from 5–10% of deputies in local representative bodies, representing at least three quarters of the municipal units within the given region.

[12] Е. Мухаметшина, ‘Владимир Путин поручил разработать механизмы отчислений в местные бюджеты от налогов и сборов’, Ведомости, 8 June 2023, vedomosti.ru.

[13] A. Toth-Czifra, ‘The municipal reform and political power in Russia’, op. cit.

[14] ‘Объем и структура государственного долга субъектов Российской Федерации и долга муниципальных образований’, Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation, 19 September 2025, minfin.gov.ru.

[15] ‘«Слишком дорогая цена за декорацию политики». Почему в России никто не хочет идти в депутаты’, Вёрстка, 20 June 2025, verstka.media.

[16] Г. Кизельгур, ‘Спустя год безвластия Новокуйбышевск получил главу’, Дзен, 19 December 2024, dzen.ru.

[17] M. Bartosiewicz, ‘Regional elites in wartime Russia’, OSW Commentary, no. 648, 10 March 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[18] ‘Почти 130 российских городов оказались под угрозой исчезновения’, The Moscow Times, 5 August 2025, moscowtimes.ru.

[19] M. Bartosiewicz, ‘The Russian public services crisis: the municipal infrastructure is in a critical condition’, OSW Commentary, no. 641, 27 January 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[20] Idem, ‘The crisis affecting Russia's public services: healthcare, education, and the postal service’, OSW Commentary, no. 608, 27 June 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[21] K. Smolyakova, ‘Municipal Reform in Russia: Public Discontent and Weak Opposition’, Riddle, 22 May 2025, ridl.io.

[22] А. Прах, В. Лавский, ‘Реформа с переменным ускорением’, Коммерсантъ, 22 June 2025, kommersant.ru.

[23] В. Никифоров, ‘Экс-губернатор Приангарья Левченко идет на выборы с программой пятилетки’, Коммерсантъ, 12 August 2025, kommersant.ru.

[24] D. Talanova, ‘Picking your battles’, Novaya Gazeta Europe, 16 June 2025, novayagazeta.eu.