Long live youth! Demography of Central Asian states

Since the break-up of the USSR, Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) has been characterised by high fertility rates and significant population growth – nearly 30 million over the past 35 years. Today, the region’s population exceeds 80 million and is relatively young, with a median age of 26.6 years. This sets it apart from most of its neighbours and leads to Central Asia being perceived as a source of labour migration. Before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the region’s residents primarily migrated to Russia; however, since then, destinations such as the EU and Turkey have gradually begun to take over this role. Alongside population growth, Central Asia is also undergoing social changes linked to urbanisation – half of the region’s inhabitants now live in cities, corresponding to the global average.

Owing to favourable demographic trends, the region has an opportunity to strengthen its political and economic position. At the same time, however, the dynamics of population growth are becoming an increasing challenge to the stability of these countries, which are struggling with inadequate infrastructural and institutional resources.

The Central Asian baby boom

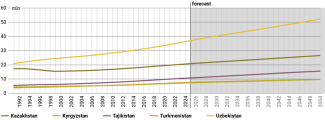

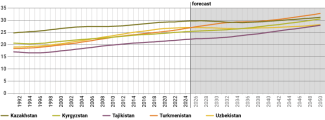

Central Asia is currently experiencing a period of rapid demographic growth. In the year the region’s countries gained independence from the Soviet Union (with a combined area of 4 million km²), their population stood at 52.9 million. Today, it is approaching 81 million, representing approximately 1% of the global population. In terms of population size, Uzbekistan leads with 35.7 million people, followed by Kazakhstan with 20.3 million. Tajikistan, Turkmenistan,[1] and Kyrgyzstan have populations of 10.4 million, 7.4 million, and 7.1 million respectively. Since 1991, the largest increases have been recorded in Uzbekistan (over 15 million more people) and Tajikistan, whose population has nearly doubled.[2] The only exceptions to the trend were Kazakhstan between 1993 and 1999, and Kyrgyzstan between 1993 and 1994, resulting from the outflow of the Slavic population (see below). In 2024, the highest population growth was recorded in Uzbekistan (+2%), and the lowest in Kazakhstan (+1.3%).[3]

Chart 1. Population of Central Asian states after 1991 and UN demographic projections

Source: ‘World Population Prospects: The 2024 Revision’, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, population.un.org.

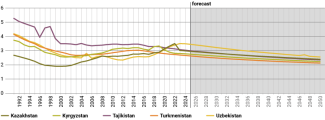

In the countries of the region, the fertility rate remains at a level ensuring generational replacement – that is, above 2.1 births per woman. Since 1991, it has fallen below this threshold only in Kazakhstan, between 1996 and 2003, as a result of an economic collapse. In 2024, the highest rate (3.5) was recorded in Uzbekistan, while the lowest (2.69) was in Turkmenistan. The fertility rate has been gradually declining in all the countries discussed, except Uzbekistan.[4]

Chart 2. Fertility rates in Central Asian states and UN demographic projections

Source: ‘World Population Prospects: The 2024 Revision’, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, population.un.org.

As previously mentioned, the median age for the region is just 26.6 years, making it one of the youngest in the world. In 2024, the youngest population was in Tajikistan (22.1 years), while the oldest was in Kazakhstan (29.6 years). In 2025, children under 15 will account for 31.4% of Central Asia’s population, individuals aged 15 to 64 (i.e. of working age) 62.2%, and older persons 6.4%. The highest share of children under 15 is in Tajikistan (35.9%), while the largest proportion of senior citizens over 65 live in Kazakhstan (9%), making it the only ‘ageing’ society in the region.[5] According to UN demographic projections, the median age in all the countries discussed is expected to rise: by 2050, it will be highest in Turkmenistan (32.8 years) and lowest in Tajikistan (27.9 years).[6]

Chart 3. Median age in Central Asian states

Source: ‘World Population Prospects: The 2024 Revision’, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, population.un.org.

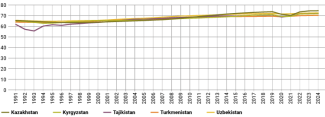

The rapid population growth results not only from high natural increase but also from the fact that the region’s inhabitants are living longer. In 2024, the highest average life expectancy was recorded in Kazakhstan (74.5 years) and the lowest in Turkmenistan (70.3 years). By 2025, these figures are expected to rise to 78.3 and 73.6 years, respectively. This marks a significant increase compared with 1991, when Uzbeks had the highest average life expectancy (65.5 years) and Tajiks the lowest (61.7 years).[7]

Chart 4. Life expectancy in Central Asian states

Source: ‘World Population Prospects: The 2024 Revision’, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, population.un.org.

Change in ethnic composition

Since gaining independence, the countries of the region have undergone a transformation in their ethnic composition. The most significant change in this regard was the outflow of the Russian population in the 1990s. During that decade, up to 80% of local ethnic Russians (270,000 individuals) may have left Tajikistan, two-thirds (180,000) left Turkmenistan, half (800,000) left Uzbekistan, and one-third left Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan (1.5 million and 300,000, respectively). The mass exodus also affected Ukrainian, German, and Polish minorities.[8] Although the primary reason for this outflow was the economic collapse, additional factors included fear of rising nationalism, loss of social status, and repatriation (in the case of non-Russian minorities). In Tajikistan, many were also forced to relocate due to the civil war between 1992 and 1997.

The share of the Russian population also declined due to the group’s lower fertility and higher mortality, often linked to an unhealthy lifestyle, including excessive alcohol consumption.[9] At the same time, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan implemented their own repatriation programmes. Between 1991 and 2025, 1.2 million ethnic Kazakhs – mainly from China and Uzbekistan[10] – arrived in Kazakhstan, while Kyrgyzstan had received over 70,000 ethnic Kyrgyz by the end of 2024, including from Tajikistan and Afghanistan.[11]

The transformation of ethnic composition can be traced using the example of Kazakhstan, the region’s most ethnically diverse country – both at the time of gaining independence and today. This situation is the result of a deliberate Soviet policy: the artificially induced famine of the 1930s, mass deportations, and intensive settlement campaigns. In the Kazakh SSR, Russians formed the majority. According to population censuses from 1939 to 1989, Kazakhs ranked second in terms of population. In 1959, they did not account for even a third of the republic’s population, and in 1989 still not even half. Before the collapse of the USSR, the republic was inhabited by 39.7% Kazakhs and 37.8% Russians, as well as significant minorities: Germans (5.8%) and Ukrainians (5.4%).[12] At the beginning of 2025, 36 years later, Kazakhs made up 71.3% of the population. The largest minority (14.6%) were still Russians, while Uzbeks accounted for 3.3% of the population. Russians mainly reside in the northern and eastern parts of the country – in the East Kazakhstan and North Kazakhstan regions they account for over 40% of the total population. Uzbeks live primarily in the south, along the Uzbek–Kazakh border. They make up more than 15% of the population in the city of Shymkent and in the Turkistan region.[13]

Urbanisation and internal migrations

Central Asia is characterised by varying levels of urbanisation. Kazakhstan leads the region in this regard: in 2024, as much as 58.4% of its population lived in cities. It is followed by Turkmenistan (54.5%), Uzbekistan (50.6%), and Kyrgyzstan (38.2%). The smallest share of urban residents is found in Tajikistan – 28.5%. Since gaining independence, the level of urbanisation has increased most significantly in Turkmenistan – by 9 percentage points – and in Uzbekistan – by 8.7 percentage points. In the 1990s, all countries in the region except Uzbekistan recorded a decline in the share of the urban population, caused by the departure of Russian-speaking residents from urban areas.[14] In Tajikistan, the civil war intensified de-urbanisation trends, while in Uzbekistan, migration to cities was slowed by a restrictive residence registration system in place until 2020, which prohibited free employment or living outside one’s registered place of residence.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the level of urbanisation in Central Asia has been steadily rising. In 2025, the region’s largest cities are Tashkent (3 million inhabitants), Almaty (2.3 million), Astana (1.6 million), Shymkent (1.2 million), and Bishkek (1.2 million). Since 1991, the populations of the first two cities have grown by approximately one million people, while those of the latter two have more than doubled. The number of residents in Astana increased fivefold following the relocation of the capital in 1997.[15] Between 2009 and 2021, as many as 13.4% of Kazakhstan’s citizens changed their place of permanent residence. The most popular destinations for relocation were the country’s three largest urban centres: Astana, Almaty, and Shymkent.[16] Kazakhs accounted for 76% of internal migrants.[17] The rapid increase in the population of metropolitan areas has led to infrastructure problems such as overcrowding, air pollution, underdeveloped public transport, poor spatial planning, and inadequate management of municipal waste.

The individual countries of Central Asia also differ in terms of population density. Kazakhstan is the most sparsely populated (8 inhabitants per km²), and is also the largest country in the region by area. In contrast, Uzbekistan is the most densely populated (85 inhabitants per km²). Areas with the highest population concentrations include the Fergana Valley (a cross-border area between Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan), southern Kazakhstan, and southern Tajikistan. These regions are frequent destinations for internal migration, while other areas are becoming depopulated. One example of this process is northern Kazakhstan: between 2009 and 2021, despite a high natural increase nationwide, the population of the country’s three northern regions declined by 3%.[18] The government-supported settlement programmes in these areas have failed to produce the expected results.[19]

Climate also influences migration patterns in Central Asia, particularly owing to limited access to water. High temperatures and droughts have a severe impact on rural and agricultural areas. The region also suffers from extreme weather events, such as floods and hurricanes. According to the World Bank, by 2050, climate-related factors could force between 1.7 and 2.4 million people in the region to change their place of residence.[20]

Migrations: not only to Russia

Labour migration is a constant feature of Central Asia’s social landscape. These departures, often seasonal, are driven by poor economic conditions, including high unemployment and low wages. Remittances from abroad account for 47.9% of Tajikistan’s GDP, 18.8% of Kyrgyzstan’s GDP, and 14.4% of Uzbekistan’s GDP (for Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, the share in GDP is close to zero).[21] According to UN data, as of mid-2024, 6.3 million citizens of the region’s countries were permanently residing abroad. Among them, the largest groups were Kazakhs (2.8 million) and Uzbeks (2.1 million), followed by Kyrgyz (0.5 million), Tajiks (0.5 million), and Turkmen (0.4 million). Altogether, this amounts to approximately 8% of the population of the countries in question.[22]

Migrants most commonly chose Russia as their destination, as it still maintains socio-economic ties with the countries of the region. In recent years, however, its attractiveness has declined. This was influenced by Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in 2022, which worsened its economic situation and caused a depreciation of the rouble, making migration less profitable. In addition, negative sentiment has emerged around newcomers, for example leading to the deportation of Tajiks following the terrorist attack at Crocus City Hall[23] and repeated instances of Central Asian labour migrants being forcibly conscripted into the military.[24]

With the worsening situation in Russia, other destinations have gained in importance – such as the European Union, Turkey, China, and South Korea. In 2023, the EU issued a record 196,000 first residence permits to citizens of Central Asian countries, 78,000 of which were employment-related. The highest number of permits was granted to Kazakhs (84,900) and Uzbeks (53,500).[25] In 2024, 250,000 citizens of the region were residing in Turkey on the basis of residence permits, primarily Turkmens and Uzbeks.[26]

However, Central Asia should not be viewed solely as a source of migration. Although still on a limited scale, it is increasingly becoming a destination for foreigners. Some of those arriving are repatriates from neighbouring countries – particularly in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan (see the section ‘Change in ethnic composition’). Others come to the region to pursue education. In this regard, Kyrgyzstan leads the way: in 2024, 50,000 foreign nationals were studying at its universities, with the most represented nationalities being Uzbeks, Indians, and Pakistanis. Medical studies were particularly popular.[27]

Occasionally, educational immigration leads to social tensions. In spring 2024, a group of over 700 people in Bishkek attacked a hostel inhabited by foreign students, primarily Pakistanis and Indians. The riots were allegedly sparked by a fight a few days earlier. Following the incident, up to 4,000 Pakistanis were reported to have left Kyrgyzstan.[28]

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine triggered a wave of emigration from Russia. Central Asian countries became one of the destinations chosen by these so-called ‘relokanty’. Their popularity was driven by visa-free travel, low living costs, and widespread use of the Russian language. According to unverified estimates, approximately 265,000 Russians arrived in the region following the outbreak of the war, though it remains unclear how many have actually stayed.[29]

An opportunity or a challenge?

Central Asia is benefiting from a demographic dividend. A low median age and high natural population growth set the region apart from its surroundings (excluding Afghanistan) and enhanced its political and economic potential. However, rapid social development presents a challenge for the region’s authoritarian regimes. State institutions often struggle to meet the growing needs of citizens, reflected, among other things, in the standard of education in overcrowded schools.[30]

Other significant problems include unemployment (from 4 to 11.6%[31]) and the lack of well-paid jobs. This issue has been partially mitigated by mass emigration, which the authorities do not regard as a threat. However, it leads to a so-called brain drain and significantly weakens the region’s human capital, hampering development.[32] This also results in the local economies and societies, particularly in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, becoming dependent on remittances from labour migrants. A collapse of this model could therefore lead to severe shocks, as illustrated by restrictions on entry to Russia after 2022. However, current trends suggest that destinations such as EU countries, including Poland, will become increasingly important.

Central Asian countries also lack well-developed family and senior policies. High fertility rates were long regarded as undesirable. Until recently, Uzbekistan actively reduced them through a policy of forced sterilisation.[33] In the region, child-related social welfare benefits are often limited to a one-off allowance at birth,[34] while caregiving is still largely performed by traditional family structures. Due to the low proportion of elderly people in the region, there is no public debate about senior care.

According to UN demographic projections, the population of Central Asia will continue to grow. By 2050, the region is expected to be home to 113 million people. Over the next 25 years, Uzbekistan’s population will increase to 52.2 million, Kazakhstan’s to 26.5 million, Tajikistan’s to 15.6 million, and both Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan will reach 9.6 million each.[35] In the long term, the societies of the region will also begin to age. The fertility rate continues to decline, a trend that may be reinforced by increasing urbanisation. The drop in birth rates could occur sooner than previous UN forecasts suggested. An earlier-than-expected demographic slowdown is already affecting countries such as Turkey,[36] Tunisia, and Latin American states.[37] The countries of the region are in no way prepared for such a scenario.

[1] The figures reported by Turkmenistan are contested. There is strong suspicion that the authorities are falsifying them. According to an investigation by Radio Free Europe, citing high-level sources in this totalitarian state, the actual population may be approximately 2.8–3.3 million, more than half less than the official statistics claim. The decline is reportedly due to concealed mass migration and low birth rates, both resulting from harsh living conditions.

[2] ‘World Population Prospects: The 2024 Revision’, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, population.un.org.

[3] ‘Population growth (annual %) – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan’, World Bank, data.worldbank.org.

[4] ‘World Population Prospects: The 2024 Revision’, op. cit.

[5] An ageing population is one in which individuals aged 65 and over account for more than 7% of the total population.

[6] ‘World Population Prospects: The 2024 Revision…’, op. cit.

[8] S. Peynrouse, ‘The Russian Minority in Central Asia: Migration, Politics, and Language’, Kennan Institute Occasional Paper Series, no. 297.

[9] M. Guillot, N. Gavrilova, T. Pudrovska, ‘Understanding the “Russian Mortality Paradox” in Central Asia: Evidence from Kyrgyzstan’, Demography, August 2011, no. 48 (3), pp. 1081–1104, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

[10] Figures for the period prior to 1 May 2025. In Kazakhstan, repatriates are granted the official status of a ‘kandas’. See ‘2025 жылдың басынан бері 5,5 мыңға жуық этникалық қазақ қандас мәртебесін алды’, Ministry of Labour and Social Protection of the Population of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 27 June 2025, gov.kz.

[11] These individuals receive the status of a ‘kayrylman’. See ‘За 2024 год статус кайрылмана получили более 1200 этнических кыргызов’, Ministry of Labour, Social Security and Migration of the Kyrgyz Republic, 11 January 2025, mlsp.gov.kg.

[12] Data from the mandatory population census conducted in 1989, Демоскоп Weekly, demoscope.ru.

[13] ‘Population of the Republic of Kazakhstan by individual ethnic groups and age groups (at the beginning of 2025)’, Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Bureau of National Statistics, 27 March 2025, stat.gov.kz.

[14] ‘Urban population (% of total population) – Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan’, World Bank, data.worldbank.org.

[15] ‘City population by sex, city and city type’, Demographic Statistics Database, United Nations Statistics Division, data.un.org.

[16] ‘Population of the Republic of Kazakhstan by individual ethnic groups and age groups (at the beginning of 2025)’, op. cit., p. 5.

[17] Ibidem, p. 77.

[18] Author’s own analysis based on: Population of the Republic of Kazakhstan: Results of the National Population Census of 2021, Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Bureau of National Statistics, pp. 11–18, stat.gov.kz.

[19] ‘Kazakhstan: Population resettlement program declared a failure’, Eurasianet, 20 February 2024, eurasianet.org.

[20] Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration, World Bank, 13 September 2021, p. 59, openknowledge.worldbank.org.

[21] ‘Personal remittances, received (% of GDP) – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan’, World Bank, data.worldbank.org.

[22] ‘International Migrant Stock 2024: Destination and origin’, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, un.org.

[23] K. Chawryło, ‘Short-term stability and long-term problems. The demographic situation in Russia’, OSW Commentary, no. 610, 3 July 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[24] M. Popławski, ‘Tajikistan: migrations as a ‘safety valve’’, OSW, 5 June 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[25] ‘All valid permits by reason, length of validity and citizenship on 31 December of each year’, Eurostat, 10 July 2025, ec.europa.eu.

[26] ‘International Migration Statistics, 2024’, TÜİK, 24 June 2025, data.tuik.gov.tr.

[27] Kyrgyzstan — Migration situation report (January – December 2024), International Organization for Migration (IOM), 26 June 2025, pp. 9–10, dtm.iom.int.

[28] A. Hussain, ‘Panic in Bishkek: Why were Pakistani students attacked in Kyrgyzstan?’, Al Jazeera Media Network, 20 May 2024, aljazeera.com.

[29] M. McGraw Olive, ‘Relokanty: Is Russia’s loss Central Asia’s gain?’, Eurasianet, 3 May 2024, eurasianet.org.

[30] A. Temirgaliyeva, ‘Astana mayor’s office to address three-shift learning and classroom overcrowding by building new schools’, Kazinform International News Agency, 28 September 2023, qazinform.com

[31] ‘Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (modeled ILO estimate) – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan’, World Bank, 7 January 2025, data.worldbank.org.

[32] P. Goble, ‘Central Asian Countries Suffer Massive Brain Drain, Putting Their Futures at Risk’, The Jamestown Foundation, 22 April 2025, jamestown.org.

[33] ‘Report: Forced Sterilization Of Women Widespread In Uzbekistan’, Radio Free Europe, 13 December 2013, rferl.org.

[34] Г. Хаджаева, Н. Осмонова, Н. Хамрабаева et al., ‘«Детей мы рожаем для себя». Как в странах Центральной Азии поддерживают рождаемость’, Радио Озодлик, 6 March 2025, rus.ozodlik.org.

[35] ‘World Population Prospects: The 2024 Revision’, op. cit.

[36] For more see Z. Krzyżanowska, ‘Turkey: a looming demographic crisis’, OSW Commentary, no. 617, 7 August 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[37] J. Burn-Murdoch, ‘Peak population may be coming sooner than we think’, Financial Times, 25 October 2024, ft.com.