More continuity than change: the Merz government’s Energiewende

Under the new government, Germany’s energy and climate policy is likely to undergo only limited adjustments rather than any fundamental shifts. Both the coalition agreement between the CDU/CSU and the SPD and the early weeks of Friedrich Merz’s leadership indicate a continuation of all the main pillars of policy aligned with the long-established Energiewende model. The announced modifications are expected to introduce a somewhat more pragmatic approach to implementing the energy transition than was the case under Olaf Scholz’s government, and to reduce the overall cost of the transformation, both for the federal budget and for end users. A loosening of debt rules will make it easier for the new coalition to continue financing decarbonisation efforts.

However, compared to its predecessors, the new government has reordered the priorities within the so-called energy policy trilemma. It has placed much greater emphasis on ensuring energy supply security and maintaining the competitiveness of the economy, especially industry, partly by reducing energy prices. In contrast, the pace of decarbonisation efforts is no longer considered a top priority.

The new government faces a growing challenge: how to continue the Energiewende while halting Germany’s deindustrialisation and maintaining public support for the transition, particularly in the transport and heating sectors. In this context, the ETS 2 system, whose implementation at the EU level is supported by the Merz government, represents a significantly underestimated socio-political risk for Germany.

The acceptance report

Germany’s energy transition accelerated during the previous legislative term, driven by the policies of Vice-Chancellor Robert Habeck and the Green Party. In the electricity sector, the Merz government’s predecessors focused primarily on reforms aimed at boosting investment in renewable energy sources and transmission networks. As a result, the number of photovoltaic panel installations soared from 5.7 GW in 2021 to 17.1 GW last year. The pace of permitting for new wind farms also increased sharply, rising from 4.1 GW in 2021 to 14.1 GW in 2023. At the same time, the backlog of approvals for long-overdue power transmission lines began to clear: over the past two years, the length of high-voltage routes granted planning approval increased from 330 km to 3,730 km. Following a hiatus in 2022 caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing energy crisis, the government completed the phase-out of nuclear power while pressing ahead with the closure of coal-fired power plants. Under new legislation,[1] 13 GW of coal capacity was withdrawn from the market.[2] By contrast, the initiative to establish a subsidy mechanism for the construction of new gas-fired power plants to replace phased-out nuclear and coal units ended in failure.[3]

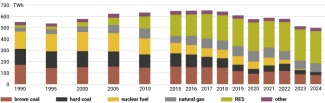

During the Scholz government, structural shifts in Germany’s electricity mix deepened. Between 2021 and 2024, the share of renewables rose from 40% to 57%, while that of coal fell from 28% to 21% (see Chart 1). These shifts were strongly influenced by a 9% drop in electricity consumption due to the economic downturn and by an increase in energy imports. Following the nuclear phase-out, Germany became a net importer of energy. At the same time, some negative consequences of the government’s approach to electricity system management have become increasingly apparent. Lower availability of conventional power plants has made it more difficult to balance the system during periods of Dunkelflaute,[4] leading to sharp price spikes on electricity exchanges, including in neighbouring countries. Grid operators, for their part, are facing growing challenges related to new phenomena known as Hellbrise and Hellflaute,[5] caused by the oversupply of renewable energy relative to demand or network absorption capacity. As a result, public debate has increasingly focused on the risk of a brownout – a controlled disconnection of an overloaded part of the grid from the rest of the system to avert the risk of a large-scale blackout.

Chart 1. Structure of electricity generation in Germany

Source: AG Energiebilanzen e.V.

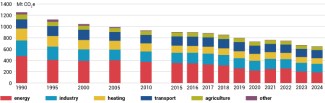

Under the Scholz government, Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions fell by 15%, bringing the 2024 total to 48% below the 1990 baseline year used in climate policy. The energy sector recorded the steepest decline (-25%), while reductions in industry and heating were more modest, at 15% each. By contrast, emissions in the transport sector remained unchanged (see Chart 2). Importantly, the declines in the first two areas were driven largely by cyclical factors – that is, lower output levels and reduced energy consumption – rather than structural changes, such as technology replacement. In this case, rising electricity and gas prices were the key factor. While the 2022 energy crisis played a central role in this increase, energy costs in Germany – already high by EU standards – are also determined to a significant extent by the country’s chosen model of energy transition.

Chart 2. Structure of greenhouse gas emissions in Germany

Source: The Federal Environment Agency.

The Merz government’s energy and climate policy agenda

In line with past practice, the CDU/CSU–SPD coalition agreement devotes considerable attention to the broader energy transition.[6] This stems from both the Energiewende’s importance in German public debate (and its prominence during the election campaign) and the lobbying efforts of various interest groups during the coalition negotiations, aimed at influencing the new government’s agenda.[7] In the agreement, the coalition partners reaffirmed their commitment to the existing climate policy targets at both the national level (climate neutrality by 2045) and the European level. They also pledged to better reconcile decarbonisation with economic competitiveness and social sensitivity. The Energiewende will continue with a more pragmatic approach that gives greater consideration to costs and energy security. Several parts of the document emphasise the need to reduce the overall expenditure associated with the transition. Lowering energy prices has also emerged as a key priority, intended to provide relief to both an economy now in its third consecutive year of crisis and to the population. The coalition has announced it will reduce electricity prices for businesses and households by at least five euro cents per kilowatt-hour, by lowering the electricity tax to the EU minimum and reducing the grid fee through state subsidies for the expansion of the power grid. Responding to the expectations of energy-intensive industries, it will cut gas prices by abolishing the so-called storage levy, which will be absorbed by the state, and reduce electricity costs by introducing special tariffs (effectively subsidies) for selected sectors. Most of these measures are already the subject of legislative work and are expected to come into force next year.

In the electricity sector, the new government has pledged to continue prioritising the development of renewable energy sources, which, under the adopted model, are expected to form the central pillar of the German power system. However, the state intends to exercise tighter control over the expansion of renewable capacity, in order to ensure that it is more closely synchronised with the much slower development and modernisation of transmission networks, and that it is grounded in more ‘realistic’ – that is, lower than previously assumed – projections of growth in electricity consumption under the Energiewende. As the starting point for reforms in this area, the Merz government has already commissioned an evaluation to assess projected electricity consumption through to 2045, determine the resulting demand for new renewable and conventional power plants, and estimate the scale of the required expansion of transmission networks.

The coalition agreement does not contain any indication that the nuclear phase-out policy could be reconsidered, which in practice all but closes the door to any potential reactivation of reactors; the gradual, years-long decommissioning process is already under way. Meanwhile, the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats have abandoned plans to accelerate the coal phase-out. While the Scholz government expressed a desire to complete this process by 2030, the current coalition has left in place the existing legal framework, under which the last coal-fired units are scheduled to be shut down by 2038.

The new government has retained the concept of using natural gas, rather than coal or nuclear power, as a backup for renewables. It has pledged to support the construction of new gas-fired power plants with a total capacity of up to 20 GW by 2030, and ultimately to establish a ‘market-based and technology-neutral’ capacity mechanism. The new cabinet has departed from its predecessor’s ambitions not only in doubling the planned capacity of new gas-fired units, but also in opening the door to carbon capture as a second long-term pathway towards decarbonising them, alongside the previously favoured transition to hydrogen.

A package of laws designed to enable investment in infrastructure for the capture, transport, and storage of CO2 is set to be one of the new government’s first legislative initiatives. This also responds to the expectations of various industrial sectors that want to prioritise carbon capture and storage (CCS) in the decarbonisation process. In a departure from the previous coalition’s approach, the new government intends to broaden the group of potential beneficiaries: CCS would be available not only to sectors where decarbonisation is otherwise unfeasible, such as cement production and waste management, but also to industries where alternative technological options exist but are prohibitively expensive, such as steelmaking and chemicals. In addition, the Merz government has pledged to maintain the main instruments for industrial decarbonisation launched by its predecessors, most notably carbon contracts for difference[8] and the planned ‘green lead markets’.[9]

In the context of reducing emissions in the energy and industrial sectors, considerable importance is also attached to the future use of hydrogen. Similarly to the Scholz government, the new coalition remains committed to accelerating the development of a hydrogen economy in Germany. However, unlike its predecessors, it plans to promote the production and use of all low-emission forms of hydrogen, rather than exclusively so-called green hydrogen. The Merz cabinet also aims to reduce regulatory barriers to hydrogen production, both at the national and EU levels, in order to lower costs and improve its competitiveness relative to other technologies.

The coalition agreement devotes relatively little attention to the transformation of the heating sector. At the request of the Christian Democrats, the document includes a pledge to ‘abolish’ Robert Habeck’s controversial heating law,[10] which promoted the gradual phase-out of gas and oil boilers, and strongly favoured heat pumps and district heating. In practice, however, the new government does not intend to repeal this legislation completely – which would, in any case, be incompatible with EU law – but rather to amend its most controversial provisions. Moreover, the cabinet has declared its intention to continue generous subsidy programmes for replacing heating sources (primarily with heat pumps) and to increase funding for the expansion of district heating networks.

By contrast, the coalition partners devoted more attention to decarbonising the transport sector. They committed to further promoting the shift to electric mobility, primarily through tax incentives for the purchase of electric vehicles, but also through regulatory measures and the accelerated expansion of the charging station network. The new government also aims to expand public transport and improve its attractiveness, with particular emphasis on the national rail network. In line with the objectives of Germany’s transport policy, the rail system is expected to handle an increasing share of both passenger and freight traffic, replacing road transport wherever feasible.

In the context of decarbonising heating and transport, the EU’s ETS 2 system is expected to play a key role. The new coalition regards it as a ‘central element’ of climate policy and has declared its support for implementing ETS 2 in 2027, in line with the European Commission’s timetable.[11] At the same time, however, the Merz government has announced it will seek to introduce EU-level mechanisms to limit the uncontrolled rise in CO2 pricing, aiming to reduce its potential negative impact on households and businesses. Budget revenues from the sale of allowances will be fully returned to consumers, either directly or through further reductions in energy prices.

Adjustments, not changes

The new coalition’s programme suggests that Germany’s energy and climate policy is unlikely to undergo a fundamental shift, with only limited adjustments to the existing course. All of its main directions will be maintained. In the energy sector, this includes continued efforts to place renewable sources at the core of the country’s power system, the withdrawal from nuclear power, the ongoing phase-out of coal, and the choice of natural gas as a backup for renewables. In the transport sector, the focus remains on promoting electric mobility and rail, in heating – on heat pumps and the transition to district heating. The cost of emissions – in effect, the rising price of fossil fuels – will remain the main incentive for citizens to switch from high-emission technologies to greener alternatives.

The intended adjustments to Germany’s energy and climate policy are primarily aimed at introducing greater pragmatism in the implementation of the Energiewende and at keeping the costs of the energy transition under control. The more practical approach, long advocated especially by industrial stakeholders, amounts to expanding the scope of so-called technology neutrality. A prime example in this regard is the decision to broaden the range of sectors allowed to reduce their production-related emissions through carbon capture. Another notable shift involves adopting a more neutral stance on hydrogen production technologies and supporting all low-emission variants, in contrast to the previous government’s clear preference for so-called green hydrogen, an approach that constrained the sector’s growth potential. The decision not to increase the pace of the coal phase-out is also indicative of this more pragmatic orientation.

With regard to reducing the costs of the energy transition, the new government is clearly striving to increase the feasibility and coordination of the required investments in renewables and transmission networks. Additional savings, compared with earlier assumptions, could also result from scaling back the push to convert gas-fired power plants to hydrogen. Crucially, the government’s focus is not on reducing current expenditure, but on avoiding a sharp increase in spending over the coming years.[12] Its key tool in this regard is the recent loosening of the so-called debt brake, alongside a marked increase in borrowing for infrastructural investments, including decarbonisation-related projects.[13] There are strong indications that these new funds will be partly used to subsidise the expansion of electricity grids, hydrogen infrastructure, and CO2 transport networks for captured industrial emissions. In this way, the government aims to avoid shifting the full cost burden onto end users.

Therefore, the new coalition has reordered the priorities within the so-called energy policy trilemma.[14] It has placed far greater emphasis on ensuring energy supply security, maintaining economic competitiveness, particularly in industry, and lowering energy prices. It will no longer drive the pace of decarbonisation aggressively. This does not mean that the process has been abandoned; rather that the Merz government will not pursue climate policy with the same level of determination as its predecessor, particularly in socially sensitive sectors such as transport and heating. Indeed, it could even take certain measures to slow the transition if political circumstances require it.

More far-reaching changes proved impossible. During the election campaign, the Christian Democrats did not promise any major overhaul of energy policy, as was clearly reflected in their policy document from last November.[15] Most of their proposals were ultimately included in the coalition agreement. During negotiations, CDU and CSU politicians advanced ideas such as reassessing the case for reactivating nuclear power plants and revising the EU’s policy of phasing out combustion engines. However, these proposals were blocked by the Social Democrats, whose positions on energy and climate policy are closely aligned with those of the Greens. Within the current coalition with the Christian Democrats, they aim to position themselves as representatives of environmental groups and as supporters of the existing Energiewende model.

Outlook for domestic politics

During this term, the CDU/CSU–SPD coalition’s energy and climate policy is likely to face strong criticism from two opposing directions. The AfD, which rejects the Energiewende in its entirety, will accuse the government of pressing on with the ‘eco-madness’ of its predecessors and of deliberately ‘strangling the economy’ and ‘impoverishing society’ for ideological reasons. On the other side, the Greens – and, to a lesser extent, the Left – will criticise the planned policy adjustments as a reckless disregard for climate change, a brake on the energy transition, and a concession to lobbying by fossil fuel-based industries. The Merz government will seek to position itself as a centrist voice of common sense. In this context, the appointment of Katherina Reiche as Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy sent an important political signal, as she has years of political and managerial experience in the energy sector. Her first weeks in office have already shown that her political goal is to shift the government’s image in energy policy[16] from ideological to more pragmatic. At the same time, Germany is likely to see the usual – and at times fierce – disputes over specific Energiewende-related projects, driven by the interests of individual parties and the support bases of the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats, including political and business circles.

From an economic perspective, one of the German government’s major challenges is to continue decarbonisation while halting the gradual process of deindustrialisation seen in recent years. Some economists have even suggested abandoning efforts to rescue (through subsidies) those industries that are unlikely to remain competitive without permanent state support after switching to low-emission production methods. In their view, the government should instead focus on sustaining innovative sectors in which Germany can still gain an advantage. However, even a controlled process of deindustrialisation would be politically damaging, socially difficult to justify, and strategically risky in several areas. There are many indications that the government will seek to preserve vulnerable industries, further expanding an already generous policy of subsidising selected sectors. This, in turn, will place an increasing burden on the federal budget, particularly given the already substantial projected costs of the transition, despite the recent increase in the borrowing limit for infrastructural investments.

Maintaining public support for the energy transition is likely to become an increasingly serious challenge for the new government, particularly in light of changes affecting the transport and heating sectors. These areas of the Energiewende are more sensitive than the electricity sector, as they require regulations that directly interfere with citizens’ lives and their decisions regarding personal property. In this context, the ETS 2 system is one of the most underestimated socio-political risks in Germany at this stage. A similar national carbon pricing scheme, in place since 2021, has already triggered tensions over rising prices in eastern states, a development that the AfD has been quick to exploit. The fuel price increases expected after ETS 2 comes into force are likely to be less severe than in other EU countries, but ultimately they will also affect the CDU/CSU and SPD electorates in western Germany. This could undermine support for the coalition in the second half of its term.

Outlook for foreign energy policy

At the EU level, Germany will seek to further advance the harmonisation of the member states’ energy policies, deepen the integration of energy markets, and expand cross-border infrastructure – all of which are particularly important for mitigating the negative effects of the transition towards renewables. In light of the readjustment of its energy policy priorities, the German government may now be willing to accept a softening of certain elements of the EU’s climate agenda, particularly in areas affecting key sectors of German industry. In a symbolic indication of its more pragmatic stance, the Merz government has signalled that it will no longer block the recognition of nuclear energy as equivalent to renewables under the EU’s regulations, such as its taxonomy.[17] In addition, Germany will push for more flexible rules on providing state aid to sectors undergoing decarbonisation. Given the country’s financial strength, now further enhanced by the recent relaxation of the so-called debt brake, this could pose a competitive threat to companies in other member states and become a major source of friction within the EU. At the same time, Minister Reiche’s initial contacts with the European Commission regarding approval for planned subsidies – for example, for building new gas-fired power plants or offsetting energy costs incurred by energy-intensive companies – indicate that, as with Habeck’s earlier initiatives, the Commission may impose strict conditions on Germany.[18]

It remains unclear whether Germany could resume hydrocarbon imports from Russia at some point in the future. For now, the Merz government has firmly rejected any possibility of activating the operational section of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, and has expressed its support for the European Commission’s efforts to implement a full embargo on Russian oil and gas. The consequences of the 2022 crisis have had a sobering effect on large parts of Germany’s political and business elites regarding energy cooperation with Russia. In the energy sector, voices questioning the need to resume gas imports from Russia are now dominant. This position is supported by the development of new LNG terminals, the signing of numerous post-2022 contracts for liquefied gas supplies (mainly with the United States), and the Energiewende’s downward effect on demand for hydrocarbons – including natural gas – despite plans to build new gas-fired power plants. Nonetheless, isolated calls for a resumption of imports from Russia have begun to surface. Should the war in Ukraine end, or even merely be frozen, such appeals will almost certainly grow louder, particularly from the influential energy-intensive industries, which will hope for lower energy prices following even a limited resumption of Russian supplies. However, pursuing this path would require great determination, including overcoming a range of legal and political challenges arising from the abrupt severance of business ties with Russia in 2022, and the resulting losses amounting to billions of euros.[19]

[1] M. Kędzierski, Germany bids farewell to coal. The next stage of the Energiewende, OSW, Warsaw 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[2] However, not all of them were decommissioned – the closure of power plants with a combined capacity of around 5 GW was blocked by the German regulatory authority (BNetzA). At its request, the plants were placed in reserve, in many cases until as late as 2031.

[3] M. Kędzierski, ‘Germany: dark clouds over the mechanism designated to support the construction of new gas power plants’, OSW, 2 December 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[4] The so-called ‘dark lull’ (Dunkelflaute) refers to a period of very low wind and solar power generation, which must be offset by output from conventional power plants and imports.

[5] Hellbrise refers to a period of very high wind and solar power generation, which the grid is sometimes unable to absorb, particularly on days with low electricity demand. A more challenging scenario for grid operators is Hellflaute, when very high solar output coincides with low wind generation. These phenomena make it necessary to temporarily shut down some wind and solar power plants to avoid compromising system stability.

[6] Verantwortung für Deutschland. Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU, CSU und SPD. 21. Legislaturperiode, koalitionsvertrag2025.de.

[7] In Germany’s political tradition, the coalition agreement is a document of considerable political significance, setting out the government’s general objectives and policy direction, as well as specific arrangements between coalition partners for the entire legislative term. Key points of contention are usually resolved during the negotiation phase, which typically lasts several weeks.

[8] M. Kędzierski, ‘Carbon contracts for difference: Germany’s new instrument to decarbonise its industry’, OSW Commentary, no. 584, 22 March 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[9] The concept of so-called green lead markets (grüne Leitmärkte) would entail a regulatory obligation for companies undertaking public investment projects or manufacturing certain goods to use low-emission products – for example, cement in construction or steel in car production. The Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action presented a preliminary outline of this concept in 2024 – for more detail, see Leitmärkte für klimafreundliche Grundstoffe. Konzept des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz (BMWK), BMWK, May 2024, bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de.

[10] M. Kędzierski, ‘Germany: a controversial heating law’, OSW, 14 September 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[11] From the outset, Germany has been one of the main advocates of implementing the EU’s ETS 2 system as a key component of the Fit for 55 package. As one of the few EU member states, Germany has already enacted legislation transposing ETS 2 into national law – see M. Kędzierski, ‘Germany adopts ETS 2 regulations’, OSW, 31 January 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[12] For example, it is estimated that accelerating grid expansion in line with current plans could cause the grid fee to double. This charge already accounts for almost 30% of household electricity bills.

[13] ‘Agency on credit: Germany releases the debt brake’, OSW Commentary, no. 657, 11 April 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[14] The so-called energy trilemma describes three key challenges/priorities faced by countries in energy policy: delivering a climate- and environmentally-friendly transition, ensuring national energy security and guaranteeing affordable energy prices, and economic competitiveness.

[15] Neue Energie-Agenda für Deutschland. Bezahlbar, sauber, sicher – Energiepolitik für den Weg zum klimaneutralen Industrieland, 5 November 2024, cducsu.de.

[16] In this context, Reiche’s remarks at a congress of the German energy industry on 4 June are particularly telling. She said: “The success of the Energiewende cannot be measured solely by the increase in installed renewable capacity” and “Energy policy is more than just climate policy.” See ‘Katherina Reiche | Keynote | BDEW Kongress 2025’, bdewonline, 4 June 2025, youtube.com.

[17] A.-S. Chassany, A. Hancock, ‘Germany drops opposition to nuclear power in rapprochement with France’, Financial Times, 19 May 2025, ft.com.

[18] M. Becker et al., ‘Wirtschaftsministerin Reiche muss ersten Rückschlag einstecken‘, Spiegel, 23 May 2025, spiegel.de.

[19] M. Kędzierski, ‘The energy Zeitenwende: Germany’s successful separation from Russia’ [in:] A. Kwiatkowska (ed.), Making up for lost time. Germany in the era of the Zeitenwende, OSW, Warsaw 2023, osw.waw.pl.