Croatia’s demographic crisis: how to address depopulation

Over three decades of independence, Croatia has lost nearly 20% of its population. The main drivers of this depopulation are mass emigration (which gathered pace after the country joined the EU in 2013) and the persistently low birth rate. In response to the deepening demographic crisis, the government established the Ministry of Demography and Immigration – the first of its kind in the European Union – which introduced a package of measures to support the fertility rate, family policy and return migration. Additionally, the government opted to liberalise migration regulations, leading to a growing share of workers from Southeast Asia in Croatia, particularly from Nepal. Despite these steps, UN forecasts remain pessimistic – by 2050, the country’s population could fall to 3.2 million, which would mean a further decline of 16%.

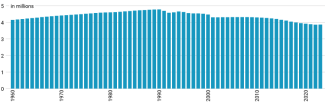

Between the end of World War II and the fall of the communist system, Croatia’s population saw gradual, if slow, growth. This trend peaked according to Yugoslavia’s census of March 1991, which recorded 4.7 million people living in Croatia – then a constituent republic of a federal state – the highest number in its history. Among them, over 500,000 – or 12% of the population – were ethnic Serbs. Just a few months later, Croatia declared independence, which directly triggered the outbreak of war.

The next census, conducted in 2001 in independent Croatia, recorded a significant population decline of 7.25%, or nearly 350,000 compared to 1991. During this period, approximately 380,000 ethnic Serbs left the country, while the number of ethnic Croats rose by more than 240,000. This increase was largely due to migration from neighbouring Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and partially offset the losses caused by mass emigration, war casualties and persistently low birth rates.

The 2011 census showed a slight easing of the downward trend – the population fell by a further 150,000 to 4.2 million. Unfortunately, the 2021 census, conducted eight years after Croatia joined the EU, indicated that depopulation had once again accelerated. Over that decade, the country lost nearly 10% of its population, with numbers dropping to 3.8 million – the lowest level in decades. This also marked the largest population loss in the country’s history. During Croatia’s first ten years of EU membership, the decline even managed to slightly outstrip that of the wartime 1990s.

Chart 1. Population of Croatia from 1960 to 2023

Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics, dzs.gov.hr.

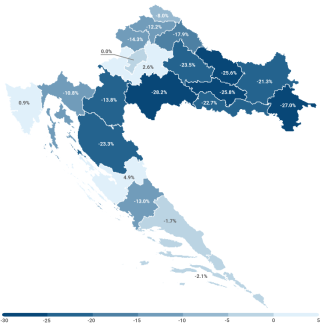

Regional inequalities: hostages to the capital

The depopulation processes are not evenly distributed across the country – their intensity and pace vary by region and županija (equivalent to a county). After World War II, Yugoslavia embarked on rapid industrialisation. As a result, development concentrated in the largest urban centres: Zagreb, Rijeka and Split. Neglect of the agricultural sector in favour of industry, and later tourism, led to large-scale migration from rural areas to cities and thus to the impoverishment of the countryside.

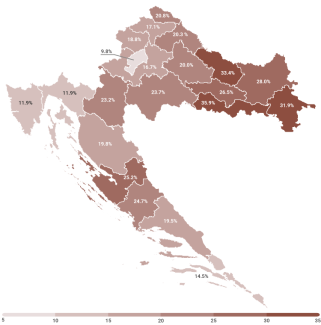

The poorest areas include the flat, agricultural eastern regions of Slavonia and Baranya, as well as the mountainous inland territories known as the Dalmatian Hinterland. Residents of these areas are far more exposed to poverty than the rest of the population. The at-risk-of-poverty rate for the Pannonian Basin – which includes Slavonia and Baranya – stands at nearly 30%, compared with just 10.5% for Zagreb.[1] The systemic problems affecting these regions go beyond low levels of economic well-being – including the lowest wages and pensions[2] and the highest unemployment – and extend to poorer access to public services such as nurseries, preschools and schools.[3]

According to the 2021 census, Zagreb (which holds county-level status) recorded the smallest population decline – falling by just under 3% over the decade. As a result, the capital now accounts for 20% of Croatia’s total population and generates nearly 30% of the country’s GDP. By contrast, over the same period, the population of Vukovar-Srijem County in the east of the country shrank by more than 20%.

Map 1. Percentage of Croats at risk of poverty in 2016

Estimates based on a financial threshold of 24,000 kuna (an equivalent of €3,186) per year.

Source: Ministry of Regional Development and EU Funds, razvoj.gov.hr.

Map 2. Change in Croatia’s population based on the 2001 and 2021 censuses

Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics, dzs.gov.hr.

Emigration: mobility by necessity and by choice

Croatia – like many countries in Southeast Europe – has typically been a country of high emigration.[4] In the past, this was driven by political reasons (including after World War II) and economic factors, particularly during the 1960s, 70s and 80s, when large numbers of expatriate workers left the country.

EU accession in 2013 and the accompanying freedom of movement significantly facilitated emigration. As a result, in the years following accession, Croatia consistently recorded negative net migration. However, economic reasons are not the only – and often not even the main – driver behind the emigration. Recent studies show that as many as 65% of Croatians aged 18 to 29 view the country’s socio-political climate negatively.[5] According to the data, 43% of respondents occasionally think about emigrating, 17% do so frequently and 12% constantly. Only 28% said they had never considered leaving.[6] The most commonly cited issues include nepotism, corruption and a sense of having no influence over decision-making processes.

The younger generation also complains that its needs – particularly in the area of housing policy – are being marginalised. According to Eurostat data, as many as 77% of Croatians under the age of 34 live with their parents – the highest proportion in the EU.[7] While this can partly be attributed to cultural norms, it is largely the result of economic barriers. Croatia currently ranks fourth in the EU in terms of property price growth – in 2023, prices rose by 12.3%.[8] One of the key factors driving prices is the activity of foreign investors, who purchase residential properties in tourism-heavy regions and convert them into short-term rentals. This reduces the availability of housing for local residents and exerts upward pressure on the market. In this context, emigration is often seen as a real opportunity to gain independence and improve living conditions.[9]

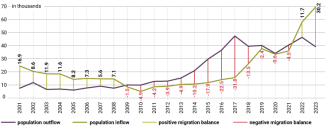

The sense of limited prospects did not disappear even after Croatia joined the EU. Despite steady economic growth – with GDP rising at an average annual rate of 2–3% between 2015 and 2020 – the competitive advantage of more developed member states in terms of employment conditions and wages has continued to encourage emigration.[10] Moreover, the pace of emigration accelerated in the years immediately following accession. The peak came in 2017, when more than 47,000 people left the country – over five times the number a decade earlier. The most common destinations are Germany and Austria, with Ireland gaining increasing popularity since 2016.

Chart 2. Key migration indicators in Croatia from 2001 to 2023

Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics, dzs.gov.hr.

Fertility: low as usual

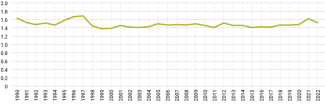

In addition to mass emigration, a key reason for Croatia’s shrinking population is the persistent reluctance to have larger families. In 2022, the fertility rate – the average number of children born per woman over her lifetime – stood at 1.53. While this slightly exceeds the EU average (1.48), it remains well below the replacement level of 2.1. Croatia last recorded a replacement-level fertility rate in the 1960s.

The decline in the fertility rate is the result of long-term social and economic changes that began during the era of socialist Yugoslavia. Among the most significant was the post-World War II wave of urbanisation. This mass movement from rural areas to cities led to shifts in lifestyle and a reduction in family size. Other important factors include the characteristics of Yugoslav social policy, such as the promotion of gender equality, secularisation and the spread of family planning awareness.

A brief and modest increase in the fertility rate (up to 1.7 births per woman) was recorded between 1995 and 1997. This was partly due to a rebound following so-called delayed parenthood – the postponement of childbearing during wartime or periods of political and social instability. After 1997, the rate returned to previous levels and has since remained within the range of approximately 1.4 to 1.6 births per woman.

Chart 3. Fertility rate in Croatia from 1991 to 2022

Source: World Bank, data.worldbank.org.

The low fertility rate is also the result of other processes, such as the declining number of marriages and the rise of late motherhood. Over the 30 years of Croatian independence, the number of marriages has fallen by nearly 22%. Croatians are entering formal relationships and having children at increasingly later stages of life. In 2023, the average age of men at first marriage was 31.7 years, while for women it was 29.3 years. Twenty years earlier, these figures stood at 27.7 and 24.9 respectively. The average age of a woman having her first child was also 29.3 – slightly below the EU average of 29.8 years.[11]

Immigration as an attempt to address labour market challenges

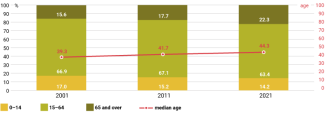

A low fertility rate combined with widespread emigration is accelerating the ageing of Croatia’s population. Over the past 20 years, the median age has risen by nearly 20%, reaching 44.3 years in 2021, according to official data (compared with the EU average of 44.7 years). During the same period, the old-age dependency ratio – which indicates the percentage of the population aged 65 and over – increased by more than 6 percentage points to over 22%. These two decades have also seen the working-age population fall: in 2001, those aged 15–64 made up nearly 67% of society, but by 2021 this had fallen to 63.4%, a drop of more than 3 percentage points.

Chart 4. Changes in the age structure of Croatian society from 2001 to 2021

Source: Author’s own estimates based on data from the Croatian Bureau of Statistics, dzs.gov.hr.

Labour shortages caused by low fertility, an ageing population and emigration have increasingly led to Croatia to relying on foreign workers to maintain economic stability and ensure the functioning of critical sectors. The most severe staffing gaps are found in construction, tourism, manufacturing and transport. Until 2021, citizens of third countries were employed under a quota-based system, which set annual limits for specific sectors. While intended to regulate the labour market, the system proved inflexible in times of crisis.[12] The current model is based on a labour market test, under which employers must obtain confirmation from the Croatian Employment Service that no unemployed Croatian or EU citizen is applying for the position. This change has resulted in a steady increase in the number of work permits issued, which has directly contributed to a positive net migration balance since 2022.

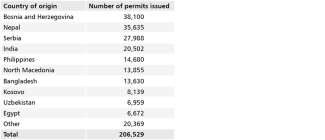

Croatia’s foreign workers have traditionally included a large share from the Western Balkans – particularly Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also Serbia, North Macedonia and Kosovo. The cultural and linguistic proximity, as well as geographic closeness, made Croatia an attractive destination for job seekers from post-Yugoslav states. However, as other labour markets – notably Germany – have opened up to these nationals, the number coming to Croatia has declined in recent years. Bosnia and Herzegovina remains an exception, continuing to account for the largest share of foreign workers.

Labour market needs – and the resulting changes in national legislation – have led to a growing influx of workers from Southeast Asia, particularly from Nepal, India, the Philippines and Bangladesh. Over a three-year period, the number of work permits issued to Nepalese citizens increased more than sevenfold – from just over 4,700 in 2021 to more than 35,000 three years later. According to preliminary data from the Croatian Ministry of the Interior, in January and February 2025, more residence and work permits were issued to Nepalese nationals than to citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[13] The low share of applications to extend work permits indicates that most Southeast Asian workers do not intend to settle in Croatia long-term, meaning their presence is unlikely to offset the population loss in a lasting way. Their role is primarily to fill immediate labour market gaps on a short-term basis.

In response to widespread abuses against foreign workers – including illegal employment and underpayment – the Croatian government amended the Aliens Act in 2025. The revisions introduced stricter requirements for employers and greater protections for employees. Key changes include extending the duration of residence and work permits from one to three years and introducing a 60-day transitional period after job loss, during which a foreign worker can remain in Croatia and seek new employment. The amendments also oblige employers to pay foreign workers the same amount as Croatian employees in equivalent roles and to provide decent living conditions. The new regulations further define the ratio of Croatian to foreign employees permitted within a given company.

Table. Number of residence and work permits in Croatia in 2024

Source: Ministry of the Interior of Croatia, mup.gov.hr.

Government response to the demographic crisis

The Croatian authorities are well aware of the country’s alarming demographic situation. In 2017, population renewal was identified as one of nine strategic national goals in the National Security Strategy.[14] In response to the deepening crisis, Croatia became the first EU member state to establish a Ministry of Demography and Immigration in 2024.[15] The newly created ministry was assigned to the national-conservative Homeland Movement (DP), which governs in coalition with Andrej Plenković’s Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ).[16]

In December 2024, the ministry unveiled a so-called demographic measures package, organised into four pillars: support for parenthood, creating a family- and child-friendly environment, revitalising depopulated areas, and encouraging the return of Croats and people of Croatian descent.[17] The government plans to spend €685 million on improving the demographic situation in 2025 alone, to be followed by €769 million in 2026, and more than €805 million in 2027.

Among the key initiatives of Prime Minister Plenković’s cabinet are: doubling the one-off birth grant from the current €309 to €618, extending paternity leave from ten to 20 days, and raising the upper limit of the allowance for the eight-month parental leave from €995 to €3,000 (the six-month maternity leave, during which mothers receive 100% of their salary, remains unchanged). An ambitious programme to expand preschool infrastructure has also been launched, aiming to improve access to early childhood education by creating an additional 22,500 places. The government also plans to expand the system of discounts for families with children at public institutions, including reduced entry fees to museums, theatres, national parks and sports facilities.

In cooperation with the Agency for SMEs and Innovation, the Ministry of Demography intends to introduce programmes aimed at strengthening the labour market in the most depopulated regions, and at improving public transport in areas affected by mobility exclusion.

Plans also include pilot programmes for returnees of Croatian descent. These are expected to offer a faster path to citizenship and labour market access, as well as eligibility for public education and healthcare services. The fact that the Croatian passport ranks ninth globally among the most attractive travel documents[18] contributed to approximately 4,000 people acquiring citizenship in 2024 – primarily returnees from South America.[19] Previous efforts to encourage the return of Croats who had moved to countries within the European Economic Area largely failed. One such initiative, the Choose Croatia (Biram Hrvatsku) subsidy, introduced in 2022, offered up to €27,000 to those returning to Croatia to start their own business.[20] The government anticipated around 4,500 citizens would apply, yet fewer than 500 did so in the programme’s two-year run.

Too little time has passed since the latest changes were introduced to allow for a reliable assessment of their effectiveness. However, Croatian demographers argue that these measures came too late and are unlikely to address core domestic challenges, particularly in the areas of housing policy and centralisation.[21]

Prospects

The demographic forecasts for Croatia are unequivocally unfavourable. According to UN estimates, the country’s population could shrink to around 3.2 million by 2050, representing a decline of approximately 16% compared with 2024. Depopulation is expected to be most pronounced in the eastern regions, while the capital region is projected to remain relatively stable in this regard – a trend that may deepen the disparity between Zagreb and the rest of the country.

Public debate on demographics has intensified significantly, particularly following the creation of the Ministry of Demography and Immigration. Experts argue that the effectiveness of government programmes aimed at boosting the fertility rate and improving family living conditions may prove limited in the face of longstanding neglect and entrenched cultural changes. In this context, immigration is increasingly seen as the only realistic means of maintaining the stability of Croatia’s economic and social systems. As a result, the focus of public discourse is shifting from the question of whether Croatia needs foreign workers to asking how their fair treatment and successful integration can be ensured. A symbolic example of the country’s changing demographic reality came during the inauguration ceremony of President Zoran Milanović, where a young Filipino woman performed a traditional Croatian song.

[1] ‘Pokazatelji siromaštva i socijalne isključenosti u 2023’, Croatian Bureau of Statistics, dzs.hr.

[3] EU- and Croatian Government-funded project on social inequality research ‘Nejednakost u Hrvatskoj’, nejednakost.cms.hr.

[4] See P. Wankiewicz, ‘The vanishing Balkans. The region's demographic crisis’, OSW Commentary, no. 647, 5 March 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[5] A. Dimitrijević, ‘Mladi iz Hrvatske ne iseljavaju samo zbog financija, već i zbog korupcije i nepotizma’, Faktograf.hr, 29 September 2024; ‘Objavljena je studija s rezultatima istraživanja u sklopu projekta „Mreža 2050 – Demografija, od izazova do odgovora”’, Mreža 2050, 19 October 2023, demografija2050.eu.

[6] Ibid.

[7] ‘Persons living with their parents or contributing/benefiting from the household income (population aged 18 to 34 years)’, Eurostat, ec.europa.eu/eurostat.

[8] ‘House price index (2015 = 100) - quarterly data’, Eurostat, ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Q3 2024 compared to Q3 2023.

[9] L. Simmonds, ‘Croatian Youth Leaving Country Because They Can’t Leave Parental Home?’, Total Croatia, 11 May 2023, total-croatia-news.com.

[10] See P. Wankiewicz, ‘The fading star pupil: ten year of Croatia's membership in the European Union’, OSW Commentary, no. 532, 18 August 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[11] ‘Fertility indicators’, Eurostat, ec.europa.eu/eurostat.

[12] For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the allocated quotas were not used due to mobility restrictions.

[13] ‘Statistika’, Ministry of the Interior of Croatia, mup.gov.hr.

[14] ‘Strategiju nacionalne sigurnosti Republike Hrvatske‘ [Croatia’s National Security Strategy], 14 July 2017, cited in: narodne-novine.nn.hr.

[15] Since 2016, Croatia had already had a Ministry of Demography, Family, Youth and Social Policy.

[16] See P. Wankiewicz, ‘Croatia: Plenković's third government, and a turn to the right’, OSW, 21 May 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[17] ‘Predstavljen paket demografskih mjera za 2025.: Demografija strateško pitanje budućnosti Hrvatske’, Ministry of Demography and Immigration, mdu.gov.hr.

[18] The Henley Passport Index is a global ranking of passports based on the number of countries and territories their holders can enter without a visa. See ‘The Henley Passport Index’, Henley & Partners, henleyglobal.com.

[19] M. Baričević, ‘Hrvatsku očekuje val useljenika iz daleke zemlje? "Dolazimo prvo na šest mjeseci, a onda..."’, Dnevnik.hr, 1 April 2025.

[20] In 2023, the programme was extended to include Argentina, Australia, Brazil, the United States, Chile, Canada, New Zealand and Peru. The financial subsidy is also available to individuals who have relocated from more developed countries to those classified as less developed.

[21] ‘Vlada donijela nove mjere. Demografi: To je pozitivan korak, ali nije dovoljno’, Index.hr, 24 November 2024.