Slovakia’s depopulation: balancing support for children and senior citizens

Slovakia, like other countries in the region, is grappling with serious demographic challenges. The number of deaths is increasingly outpacing the number of births, largely due to a declining fertility rate, and the migration balance is barely above zero. This translates into a recorded and projected decline in population, with the key question concerning not whether the population will fall, but rather by how much it will fall. The most pessimistic forecast, which the latest figures seem to confirm, predicts that the current population of nearly 5.5 million will shrink to under 5 million by the middle of the century, and possibly to as low as 4.2 million by 2080.

In Slovakia, the differences between specific national-ethnic groups are a separate aspect of the country’s demographic profile. Besides a significant Hungarian minority, the country has the second-biggest share of Roma population in the EU. The Roma community is characterised by a notably higher birth rate compared to the national average. Nevertheless, the negative attitude of a significant part of society towards the Roma community (which certain political groups take advantage of) was one of the reasons behind the long-standing caution in taking clear steps to support families with children. Furthermore, the instability and polarisation of the political scene contributed to the fact that the scope of the relatively ambitious pro-family programmes introduced in recent years was significantly scaled back shortly after Robert Fico’s return to power in 2023.

The worst figures in history

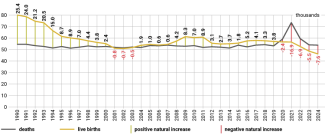

The demographic data for 2024, published at the end of March 2025, reveal that the negative demographic trends in Slovakia are worsening, with many statistics reaching record lows. In 2024, the number of births fell to the lowest level since the establishment of the independent Slovak state in 1993, with only 46,000 children born. This downward trend has continued every year since 2018 (see Chart 1). The natural population growth was negative for the fifth consecutive year, and its magnitude was the second highest in the country’s history – surpassed only in 2021, when there was a particularly high number of deaths, primarily due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

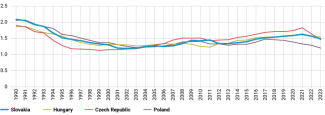

The declining number of babies in Slovakia results from two main factors: both the population of women of reproductive age and the birth rate per woman are falling. According to Eurostat data (latest from 2023), the total fertility rate (TFR) was last close to the replacement level of 2.1 in 1990 (see Chart 2). In 2023, the TFR fell for the third consecutive year, reaching a level lower than in any year since 2016. Nevertheless, Slovakia’s rate of 1.49 remains the eighth highest in the European Union – above the EU average of 1.38 – and the second highest among the Visegrád Group countries, after Hungary.

Chart 1. Basic demographic indicators in Slovakia in 1990–2024

Source: author’s own calculation based on statistics compiled by the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic.

Chart 2. Total fertility rate (TFR) in Slovakia compared to other states of the region in 1990–2023

Source: author’s own calculation based on Eurostat statistics.

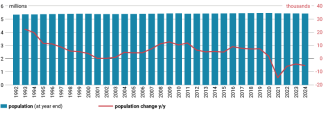

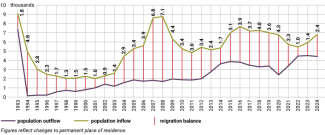

In 2024, for the fourth consecutive year, Slovakia’s total population had declined by the end of the year (see Chart 3). This ongoing decrease is particularly notable because it had not occurred prior to 2021 – not just since the breakup of Czechoslovakia, but also throughout the entire post-war period. Although the migration balance has remained positive over the past four years, it has been far too modest to offset the negative natural increase. In fact, over the last two years, the natural population decline has outstripped the migratory gain by three to four times. This imbalance reflects both a relatively low number of immigrants and a persistently high level of emigration in the past decade (see Chart 4).

While 2022–2023 saw the most significant influx of immigrants to the Czech Republic since the start of the post-communist transition, Slovakia experienced a more modest trend. Looking solely at the decade between 2014 and 2023, Slovakia recorded higher annual immigration than in either 2022 or 2023 on as many as six occasions. Moreover, the period from 2022 to 2024 saw record high emigration from Slovakia. Effectively, these years witnessed the highest number of people leaving the country since its independence – second only to 1993, a unique year shaped by the dissolution of Czechoslovakia. In 2024, the primary destinations for Slovak emigrants were the Czech Republic (44%) and Austria (17%). As regards immigration, the most common sources were the Czech Republic (21%, mostly return migration of Slovaks) and Ukraine (20%). However, in 2022–2024, unlike the Czech Republic, Slovakia did not experience a comparable influx of Ukrainian refugees intending to settle there for longer.[1]

Chart 3. Slovakia’s population in 1992–2024

Source: author’s own calculation based on statistics compiled by the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic.

Chart 4. Slovakia’s basic migration indicators in 1993–2024

Source: author’s own calculation based on statistics compiled by the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic.

The causes of the crisis

The recent decline in Slovakia’s population is primarily driven by negative natural population growth and an insufficient (though positive) net migration to offset it. With respect to natural growth, the country reflects broader trends observed in the Western world: a long-term stable number of deaths (excluding the COVID-19 pandemic years) paired with a falling fertility rate. Another factor contributing to the declining birth rate in Slovakia is the shrinking number of women of reproductive age (15–49). At the start of the 21st century, there were around 1.45 million women in this demographic group – an all-time high – but over the following two decades, this number decreased by more than 200,000. This downward trend is expected to continue.[2] Additionally, the fertility rate has been negatively affected by a de facto contraction of the reproductive window due to women postponing the birth of their first child. Between 1993 and 2022, the average age at first childbirth rose by nearly six years, from 22.4 to 28.3.[3]

There have been analyses aimed at identifying the causes behind the decline in the total fertility rate (TFR) which aim to frame the issue from a global perspective, given that similar trends – albeit with varying intensity – have occurred across much of the world, particularly within the broadly understood Western civilisation. The global fertility rate has dropped from 3.3 in 1990 (having stood at around 5 in the 1960s) to 2.3 in 2022, while in Europe itself it had already fallen below the replacement level (2.1) as early as the 1970s.[4]

Models based on the theory of demographic transition describe changes to the initial pattern, i.e. large families with high child mortality.[5] Improvements in hygiene and nutrition, along with the development of health care services, initially only reduced the number of deaths. After some time, a decline in birth rates followed, caused by several changes, including longer periods of education for women, a reduced demand for labour due to falling mortality rates, and the automation of production and agriculture. These shifts were accompanied by social changes, such as a stronger emphasis on the pursuit of material aspirations – made more achievable due to economic development – and the increased participation of women in the labour market. From an economic perspective, the sacrifice associated with having children becomes greater the more attractive the alternatives become, such as well-paid and fulfilling jobs or opportunities for further education.

The next phase brought about the consolidation of the model characterised by low mortality and low birth rates, along with the spread of contraception, the reduction or elimination of the need for children to support their parents in their old agedue to efficient pension systems), and the postponement of starting a family due to the desire to focus on self-development. This is accompanied by ongoing urbanisation and the anonymity associated with city life, as well as secularisation, which weakens the capacity of major religions to promote family values. At the same time, increasing social expectations lead many parents to invest limited resources in fewer children to ensure better prospects for them. Thus, in a further phase – despite ongoing economic growth – the birth rate declines more rapidly than the death rate. Statistics for wealthy, middle-income, and poorer countries alike show a negative correlation between life expectancy and the fertility rate, i.e. increasing life expectancy and a declining TFR almost always occur simultaneously.[6]

This theoretical finding can be applied to the analysis of the situation in Slovakia by comparing the fertility rate in various regions (in the eight so-called ‘kraje’) with selected socio-economic indicators.[7] Thus, applying Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient shows a strong correlation (values from 0.8 to 1 inclusive, positive or negative) in the case of the registered unemployment rate (+0.8) and the risk of poverty (also +0.8), indicating that the fertility rate is higher in areas where problems finding employment or general material hardship are more pronounced. A moderately strong correlation (values from 0.4 inclusive to 0.8 exclusive, positive or negative) occurs for the level of disposable income per person (-0.62) – a decline in income typically coincides with an increase in the fertility rate. These three correlations seem to confirm the theoretical assumption that the decision to become a parent is more difficult when the time devoted to children is competing with attractive, well-paid employment that guarantees a comfortable life. In other words, the greater the attachment to work and the subjective comfort associated with having leisure time, the higher the opportunity cost of time spent on parenthood.

There is a moderately strong negative correlation between the regional fertility rate and both the average age of women at childbirth (-0.63) and the prevalence of hormonal contraception use (-0.7) – meaning that the higher these values are, the more likely it is that the TFR will be lower. The fertility rate also shows a medium-level correlation with the share of followers of major Christian denominations (+0.41), which may indicate the influence of religious motivation, although more recent data on the frequency of religious practice in individual regions (which is currently unavailable) would be more accurate in this regard. On the other hand, there is a weak correlation (values above −0.4 and below 0.4) between fertility and the share of women with higher education (+0.04), regional GDP level (-0.1), and the average salary (-0.15).

In the Slovak debate on demographic changes, attention is drawn to the sense of uncertainty in recent years, related to high inflation and the war in neighbouring Ukraine. These factors may have negatively affected decisions to start or expand a family. Nevertheless, a recent EU survey (Eurobarometer) conducted among the young citizens of EU member states (aged 16–30) showed that Slovaks are particularly affected by challenges related to the cost of living (36% of responses; respondents could select up to three problems from a list of 11), job security (30%), economic stability (26%), and housing availability (25%).[8] This shows that economic issues are more important to them than concerns about an escalation of the armed conflict. According to Eurostat data, in 2024 Slovakia had the fourth-lowest GDP per capita in the EU when adjusted for purchasing power (75% of the EU-27 average), ranking above only Bulgaria, Greece, and Latvia. A similar picture emerges from another Eurostat ranking based on a different measure of prosperity – actual individual consumption (AIC): in this regard, only Hungary and Bulgaria recorded a lower level relative to the EU average than Slovakia (75%).

A debate shadowed by the Roma population

Slovakia’s multiethnic composition is one of its key distinguishing features within the Visegrád Group, particularly its large Roma minority, which plays an important role in discussions around boosting the fertility rate. However, even determining the exact proportion of Roma living in the country is problematic. The OECD estimates the Roma share of the population to be 9%, which is the second-highest in the EU after Bulgaria (9.9%) and just ahead of Romania (8.6%).[9] By contrast, the results of the latest census reflect a significantly lower share. Taking into account both the respondents’ declared primary and secondary nationality, there were over 156,000 Roma in Slovakia in 2021, amounting to 2.9% of the population. This discrepancy is linked to the complex nature of Roma identity, which often overlaps with the Slovak or Hungarian one (Hungarians make up nearly 8% of the population according to the census). The Atlas of Roma Communities,[10] which reflects the perception of Roma communities by other residents, rather than Roma people’s self-identification, reported a share almost three times higher (8% in 2019).

Applying Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the total fertility rate (TFR) and the proportion of Roma in a given district (okres) corroborates the common perception that the Roma have large numbers of children. The correlation is positive (i.e. an increase in the share of Roma aligns with growing fertility) and relatively high when the proportion is measured using data from the aforementioned Atlas (0.57, with the maximum value being 1), as well as when using the figures from the latest national census (0.77)[11] However, this relationship is not determinative: statistically, a 1 percentage point increase in the Roma share of a given district’s population is linked to a rise in the fertility rate of no more than 0.06. A stronger correlation exists between the Roma share and the unemployment rate (0.83–0.84), as well as the proportion of the population receiving social welfare benefits (0.72–0.88). These latter relationships contribute to the often negative perception of this segment of the population among the rest of society.

This translates into a negative attitude towards this group on the part of many leading politicians, resulting in a reluctance to implement social programmes that support fertility, particularly in the form of financial transfers. The discussion on additional support for families with children provides a good example of the shape these political debates take. It culminated in the adoption of a corresponding package in 2022 by a parliament dominated by the centre-right.[12] The main antagonists at the time were Robert Fico, the leader of the opposition left-wing nationalist party Smer (currently the prime minister), and Igor Matovič, the head of the largest party in the ruling coalition, the anti-corruption OĽaNO (now the Slovakia movement). Fico accused the then-government of ‘buying off the Roma’ ahead of the upcoming local election and of ‘not caring about anyone else’.[13] When Matovič was still prime minister (2020–2021), Smer leader Robert Fico referred to him as the ‘prime minister of the Gypsies’. Fico had also spoken about alleged abuses of social welfare benefits by the Roma during his own earlier term as PM (2016–2018). In 2019, when far-right activist Milan Mazurek lost his parliamentary seat due to his anti-Roma remarks in the media, including the claim that ‘Gypsies should not be able to do business by having children’, Fico expressed support for him. According to the current prime minister, Mazurek – now a Member of the European Parliament representing the Republika party – was merely saying ‘what almost the entire nation thinks’.

Matovič and his supporters argued that support for families with children ‘must become a priority for Slovakia, as it is an investment in the country’s future’.[14] In their electoral platform, Matovič and his aides made these issues one of its main pillars – immediately after the fight against corruption – proposing a series of measures targeted at families with children, ranging from financial transfers to policies facilitating the combination of work and parenthood. A separate chapter was dedicated to the Roma issue, aiming to propose actions for better integration of this community. Matovič created a Roma platform within the party (under the name Pačivale Roma, meaning ‘Honest/Responsible Roma’ in their language) and promoted Roma candidates from his lists to seats in the National Council (including, in 2012, the first ever Roma member of this body) and the European Parliament.

Nevertheless, even he – despite drawing inspiration from programmes such as Poland’s ‘Family 500 Plus’ – had to adapt his proposal to Slovak conditions. This meant that the headline slogan ‘€200 per child’ effectively primarily referred to a combination in which financial transfers played a minor role, while tax relief and subsidies for extracurricular activities made up the majority. The package, adopted by the National Council in spring 2022, provided from January 2023 a maximum of €100 in tax relief per child (up to age 15), €60 for extracurricular activities (for children of 5 to 18 years old), and €40 in direct financial benefits (paid up until the child reaches 25, if it is dependent).

Regardless of the Roma-related narrative applied by both the left and the far right, two distinct camps quickly emerged within Slovakia’s expert debate. Supporters of the package pointed to years of neglect in the area of family policy and highlighted that Slovakia had the lowest spending in this area in the region relative to GDP – 1.8% in 2019, compared to 3% in Poland, 2.5% in Austria, and 2.4% in Hungary.[15] Opponents pointed to unclear funding sources and the abuse of the fast-track legislative procedure. These concerns led then-President Zuzana Čaputová – Fico’s political rival from the liberal wing of the political spectrum – to veto the section of the reforms set to take effect more than six months after their adoption. Following the veto’s rejection, she referred the package to the Constitutional Court. Without waiting for the court’s ruling, the government introduced further amendments: starting in early 2023, the financial benefit was increased to €60, the tax credit to €140, and the launch of the extracurricular activity subsidy (known as krúžkovné) was postponed until 2025, as the Ministry of Education had not managed to prepare the necessary implementation system.

After the change of government in autumn 2023, the left-wing nationalist cabinet led by Robert Fico significantly scaled back family support measures while maintaining bonuses for pensioners, an important electorate for the ruling coalition parties. The new government not only abandoned the previously announced subsidies for extracurricular activities but also, as part of fiscal consolidation efforts, substantially reduced both the maximum child tax allowance (from €140 to €100) and the accessibility of this benefit. In the latter case, the ruling bloc faced relatively little resistance, as some experts had already criticised the mechanism for disproportionately favouring wealthier parents (the higher the income, the greater the tax relief).

Slovakia has thus implemented a system since the beginning of 2025 in which eligibility for claiming a tax deduction for children depends on the amount of gross monthly income (from €2,470, the maximum deduction is no longer available – it decreases as income rises, and those earning more than €3,630 are not entitled to any deduction at all). Additional changes include the elimination of eligibility for deductions for children over 18 years old (previously available, for example, if they were in education), and a halving of the deduction for those aged 15–18. At the same time, according to media reports, the government is considering further cuts to the child cash benefit. Options include halving it (to €30) for everyone except the poorest citizens, or ending payments to parents of students aged 18–25 entirely.[16]

The prospects for a fundamental shift towards more generous support for families with children are uncertain in the foreseeable future. Although some parties of the current opposition – especially Matovič’s party, which is regaining popularity, and the Christian Democrats – advocate a stronger focus on family policy, it seems unlikely that they will once again set the tone for Slovak politics. While these parties would likely be part of any governing coalition should Fico lose the 2027 parliamentary election, it would probably be the liberals from Progressive Slovakia who would hold decisive influence. These liberals continue to emphasise the limitations of the Slovak budget and so far have prioritised issues such as security and digitisation over strengthening pro-natalist policies. In response to demographic challenges, they would be more inclined to loosen migration policy. However, it cannot be ruled out that the introduction of some targeted measures supporting families with children could form part of a package of policy compromises which such a broad coalition would need to negotiate.

According to the latest available Eurostat data (for 2022), Slovakia allocated 1.78% of its GDP to cash benefits for children (up from 1.43% in 2019, which was the last full year of Smer’s government before the change in power).[17] This was the sixth highest figure in the EU (Poland topped the list with 2.39% of GDP), and higher than the results for the Czech Republic (1.47%) and Hungary (1.21%). In terms of total spending on families with children within the social welfare system, Slovakia spent 1.92% of GDP (up from 1.67% in 2019). This placed the country 13th in the EU (Germany allocated the most, at 3.4% of GDP), again ahead of Hungary (1.72%) and the Czech Republic (1.64%). Given the changes introduced by the current ruling coalition, these indicators are expected to be significantly lower for 2025.

Forecasts: the scale of depopulation and preventive measures

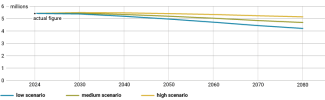

Slovakia’s main demographic forecast anticipates a population decline by 2080 under all three projected scenarios (see Chart 5).[18] These scenarios differ in terms of the expected scale of the decline and the timing of when the country’s population will begin to decrease permanently. Even the high variant assumes that a lasting population decline will begin no later than 2033, with a reduction of 5% by 2080 compared to the official 2024 figures.A body affiliated with the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic, published a report in 2024, whose authors included researchers from Comenius University in Bratislava and the Slovak Academy of Sciences; it did not, even in its low variant, anticipate as sharp a decline as that recorded in 2024. Should developments follow a path close to the so-called low scenario, Slovakia’s population would contract by as much as 22% by 2080, leaving just 4.2 million individuals. The last time the country had so few residents was in the early 1960s.[19]

The forecast is based on the assumption that the negative trend in natural population growth will persist. In the low and medium scenarios, this trend is expected to continue uninterrupted, while in the high scenario, it will become a permanent feature starting in 2028. Moreover, even in the low scenario, the total fertility rate (TFR) is assumed to remain above 1.6 for most of the projected period (and even higher in the other two scenarios), despite the fact that it was already lower than this in 2022–2023. Additionally, the current level of net migration most closely aligns with that projected in the low scenario.

Chart 5. Forecasts for Slovakia’s population until 2080

Source: author’s own calculation based on: B. Šprocha, B. Vaňo, B. Bleha, ‘Kmeňová populačná...’, op. cit.

Slovakia will not escape the demographic challenges common to the vast majority of European countries. Median age is expected to rise from 42.2 years old in 2024 to approximately 47 by 2080 (ranging from 47 to 47.3 depending on the scenario). The economic dependency ratio, which shows the number of people aged 0–14 and 65+ per 100 working-age individuals, is projected to increase from the current 53% to between 77% and 82.5%. The peak of this index is anticipated in the late 2050s, when it may exceed 88%. This figure will then start to fall due to the large generation born during the period of Czechoslovak normalisation, mainly in the 1970s (known as Husákove deti, literally Husák's children, after a Czechoslovak communist leader), beginning to die off. This entire demographic shift will be driven primarily by the growing proportion of elderly people. The old-age index – the ratio of the population aged 65+ to those aged 0–14 – is currently 118%. From the 2050s onward, this indicator is expected to surpass 200% in all forecast variants, meaning that, as is often said, ‘there will be twice as many grandparents as grandchildren’.

The projected course of events necessitates adjustments to the pension system. In 2025, Slovakia reinstated the mechanism for gradually postponing the retirement age. This mechanism had previously been abolished on 1 January 2020 by the left-nationalist government of Peter Pellegrini – just under two months before the parliamentary election. It was reinstated through the votes of the victorious centre-right coalition, though its implementation was scheduled with a delay. The first cohort affected by the new rules includes individuals born in 1967, who will not retire precisely on their 64th birthday (as was the case for those born a year earlier), but one month later. The Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family is expected to update these calculations in five years, depending on the average life expectancy recorded at that point. However, the retirement age reduction bonus for raising children has been preserved. Designed partly to motivate child-rearing, this benefit allows an individual to lower their retirement age by six months for each child raised (up to a maximum of one and a half years). It is most often awarded to women, and only exceptionally to men. In 2026, the ministry will set the retirement age for the next cohort.

The lack of realistic prospects for reversing the negative trend in birth rates means that greater emphasis will be placed on improving the utilisation of the existing population potential to meet labour market needs. This includes both the activation of the Roma community – mentioned in Prime Minister Fico’s government programme – and the effective management of qualifications among foreigners who have arrived in Slovakia in recent years. The latter issue was highlighted by the Supreme Audit Office of the Slovak Republic in a report published in April 2025.[20] The office criticised the Slovak government for its ‘prolonged inaction in the field of policies and programmes facilitating the social integration of third-country nationals’, describing this conduct as ‘irresponsible’.

It also cites the World Talent Ranking, which reflects the level of investment in developing talent among a country’s own citizens and the attractiveness of local opportunities for foreign professionals. Slovakia is ranked 53rd out of the 67 countries evaluated. Among EU member states, it ranks ahead of only Bulgaria.[21] Slovakia also lags clearly behind other countries in the region in terms of the number of EU Blue Cards issued – these are temporary residence and work permits for highly qualified workers from outside the EU. Between 2021 and 2023, Slovakia issued 36 times fewer Blue Cards per capita than Poland and 15 times fewer than the Czech Republic (although more than twice as many as Hungary).

The government led by Robert Fico is aware of these challenges. Despite its consistently anti-immigration rhetoric, it is pragmatically opening up the Slovak labour market. The focus is primarily on attracting culturally similar citizens from the former Yugoslavia and the former USSR.[22] So far, the effects of these efforts have been insignificant. Since mid-2023, there has been an upward trend in the number of job vacancies, which reached approximately 100,000 at the beginning of 2025[23] (with 2.65 million individuals employed). The unemployment rate continues to decline and in 2025 was at 5% (according to EU methodology). Thus, it cannot be ruled out that more decisive action will be needed in this area. Despite his rhetoric, which is critical of the Kyiv government’s policies, Fico has stated that he wants Slovakia to be even more open to Ukrainians, highlighting the linguistic similarity and their often strong educational background.[24] Indeed, Slovakia ranks among the EU’s top countries in terms of the number of Ukrainian refugees accepted relative to population size. At the end of March 2025, there were 24 such refugees per 1,000 inhabitants, placing the country fifth in the EU.[25]

[1] See K. Dębiec, ‘Czech demography: once a model, now a cause for concern’, OSW Commentary, no. 653, 21 March 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[2] B. Šprocha, B. Vaňo, B. Bleha, ‘Kmeňová populačná prognóza Slovenska (2022–2080)’, Infostat, Bratislava 2024, humannageografia.sk.

[3] Z. Vitková, ‘Demograf: Slovensko bude o 50 rokov menej početné, etnicky pestrejšie a staršie’, Denník N, 8 May 2024, dennikn.sk.

[4] Figures compiled by the World Bank.

[5] See for example B. Zaidi, S.P. Morgan, ‘The Second Demographic Transition Theory: A Review and Appraisal’, Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 43, 2017, p. 473–492, annualreviews.org; M. Doepke. A. Hannusch, F. Kindermann, M. Tertilt, ‘The economics of fertility: a new era’, NBER Working Paper no. 29948, NBER, April 2022, nber.org; O. Galor, ‘The Demographic Transition: Causes and Consequences’, Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit, Discussion Paper no. 6334, January 2012, after: d-nb.info.

[6] See M. Lázňovský, P. Kasík, ‘Víc dětí už na planetě nebude. Jednoduchá vysvětlení proč už na to nestačí’, Seznam Zprávy, 12 April 2025, seznamzpravy.cz.

[7] Author’s own calculation, data for 2022. The socio-economic indicators for specific regions (kraje) used in the calculation come from the database of the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic, while those pertaining to the fertility rate recorded at the regional level are from: B. Vaňo, V. Pilinská, B. Šprocha, B. Bleha, ‘Populačná prognóza krajov a okresov Slovenska (2023–2050)’, Infostat, Bratislava 2024, humannageografia.sk.

[8] ‘EU challenges and priorities: young Europeans’ views’, Flash Eurobarometer 556, European Commission, March 2025, europa.eu/eurobarometer.

[9] M. Bednarik, S. Hidas, G. Machlica, ‘Enhancing the social integration of Roma in Slovak Republic’, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, no. 1551, May 2019, oecd.org.

[10] Á. Ravasz, Ľ. Kovács, F. Markovič, ‘Atlas rómskych komunít 2019’, Bratislava 2020.

[11] P. Korec, P. Ďurček, V. Bačík, ‘Rómovia sú na Slovensku už 700 rokov; ich počet, rozmiestnenie a vzťah k vybraným spoločenským javom’, Acta Geographica Universitatis Comenianae, vol. 66, 2022, no. 2, pp. 125–163, humannageografia.sk.

[12] K. Dębiec, ‘Słowacja: prorodzinna ofensywa rządu’, OSW, 15 June 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[13] R. Gehrerová, ‘Fico útočí na vládu cez Rómov. Podľa splnomocnenca tak chce prekryť svoje vlastné problemy’, Denník N, 22 April 2022, dennikn.sk.

[14] The party’s political platform ahead of the 2020 parliamentary election, obycajniludia.sk.

[15] OECD statistics, after: compareyourcountry.org.

[16] I. Sladkovská, ‘Vláda má na stole 3 scenáre, ako by štát mohol okresať prídavky na deti, tvrdí opozícia’, Peniaze.sk, 16 April 2025.

[17] Eurostat statistics, ec.europa.eu/eurostat.

[18] B. Šprocha, B. Vaňo, B. Bleha, ‘Kmeňová populačná...’, op. cit.

[19] D. Jurčová et al., ‘Obyvateľstvo Slovenska 1945–2000’, Infostat, Bratislava 2001, infostat.sk.

[20] ‘Správa o výsledku kontroly 2025. Integračná politika štátu’, Najvyšší kontrolný úrad SR, 2025, nku.gov.sk.

[21] Other states of the Visegrád Group ranked 30th (Czech Republic), 36th (Poland) and 50th (Hungary). The ranking is compiled by the International Institute for Management Development (IMD), a prestigious Swiss business school.

[22] J. Fabok, ‘Fico chce zaplniť slovenský trh práce migrantmi. Vláda navýšila počty víz pre cudzincov o tisícky’, Pravda, 29 February 2024, pravda.sk.

[23] M. Doliak, ‘Miera nezamestnanosti sa udržala na úrovni 5,9% aj v januári 2025’, National Bank of Slovakia, 21 February 2025, nbs.sk.

[24] T. Zemko, ‘Budeme druhý Detroit, hovorí Fico. Chce sa zamerať na Ukrajincov a stavať nájomné byty pri investíciách’, Pravda, 18 March 2024, pravda.sk.

[25] ‘Beneficiaries of temporary protection by citizenship – per thousand persons’, Eurostat, ec.europa.eu/eurostat.