Germany: a significant drop in the number of asylum applications

In 2024, a total of 230,000 first-time asylum applications were submitted in Germany – a 30% decrease compared to 2023. This trend deepened in Q1 2025, when 36,000 applications were lodged, representing a year-on-year drop of 45%. The most significant declines concerned nationals of Syria (-50%), Afghanistan (-42%), and Turkey (-61%).

The decline in the number of asylum applications is primarily due to external factors – above all, the reduced number of individuals reaching the EU. According to Frontex, in 2024, 66,000 individuals illegally crossed its borders via the central Mediterranean route (compared to 157,000 in 2023), and 21,000 via the so-called Balkan route (down from 99,000 the previous year). Since November 2024, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) has suspended the processing of asylum requests from Syrians. Additionally, the decrease in applications is partly attributable to the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad’s regime and the return of some Syrians from Turkey to their homeland. Germany’s Interior Ministry has also welcomed the improvement in the economic and security situation in Libya and Tunisia, which is helping to curb the influx of refugees from the region.

The decline in the number of applications has also been influenced by ongoing random checks at Germany’s borders, the refusal of entry to individuals attempting to cross the border illegally (entry is denied in approximately 55% of such cases), and the increase in personnel within the Federal Police, which is partly responsible for border protection. Other important factors include Berlin’s declared intention to reduce access to social welfare benefits for refugees (including the replacement of cash with in-kind support or vouchers), the increasing effectiveness of deportations, and the incoming government’s declarations regarding the restriction of migration (see below).

More individuals deported

In 2024, a total of 20,084 individuals were deported from Germany – approximately 25% more than in 2023 (16,000). Of these, 5,827 individuals were transferred to other EU member states responsible for processing their applications under the Dublin III Regulation. In 2023, there were 5,053 such cases, representing an increase of around 15% year-on-year. The improved effectiveness of deportations is partly due to the tightening of regulations in 2024, including the designation of Georgia and Moldova as safe countries of origin, the expansion of powers granted to the Federal Police, and an increase in the number of detention places for individuals subject to deportation proceedings.

Chart 1. Countries of origin of migrants most frequently deported from Germany in 2024

Source: author’s own calculation based on figures compiled by the Federal Ministry of the Interior of Germany.

Chart 2. Countries of origin of migrants who left Germany voluntarily in 2024

![]()

Source: author’s own calculation based on figures compiled by the Federal Ministry of the Interior of Germany.

In 2024, Germany submitted 74,583 requests for the transfer of migrants to other countries under the EU’s Dublin III system, of which 44,431 were accepted. However, only 5,827 transfers were ultimately carried out (13%). The greatest difficulties arose in transferring migrants to Southern European countries: Italy accepted only three individuals (despite agreeing to 10,402), Greece received 22 (of 219 approved), Bulgaria accepted 290, and Croatia 533. At the same time, Germany received 14,984 transfer requests, of which 10,112 were approved and 4,592 implemented. The gap between the number of approved cases and those actually completed is mainly due to difficulties in locating migrants who disappear before deportation, as well as administrative shortcomings on the German side, such as poor coordination and staff shortages. Since 2022, Italy has refused to carry out transfers due to the strain on its asylum system. In addition, German courts have repeatedly blocked transfers to Greece because of poor living conditions in the country’s refugee camps.

Similar problems occur in the case of deportations. In Germany, 33,717 deportation attempts failed – 62% of all planned deportations. In the vast majority of cases (32,567), deportations were cancelled before the migrant was handed over to the Federal Police. The main reasons for these failures include: failure to escort the individual to the deportation site, last-minute revocation of decisions, refusal of transport by airlines or pilots, missing documentation, medical concerns, passive resistance by the deportee, and other legal interventions. At the same time, the number of individuals required to leave the country fell – by as much as 27% compared to 2022. This was partly due to the granting of so-called Chancen-Aufenthalt status to many individuals with tolerated stay, allowing them to legally reside in Germany for 18 months. By the end of 2024, 50,000 individuals had taken advantage of this opportunity, around 10,000 of whom had already obtained permanent residency.

Although the number of deportations in Germany has increased, there are still 220,000 migrants who are obliged to leave the country. Deportation has been temporarily suspended in 81% of these cases (approximately 178,000), despite the formal obligation to leave. The remaining individuals are required to leave the country immediately. The main reasons for granting tolerated stay include, above all, the lack of documents and unverified identity. Other factors influencing such decisions include family ties with other foreign nationals residing in Germany, as well as humanitarian and personal considerations, such as educational commitments or the need to care for sick relatives.

Turnbacks at borders are increasingly effective

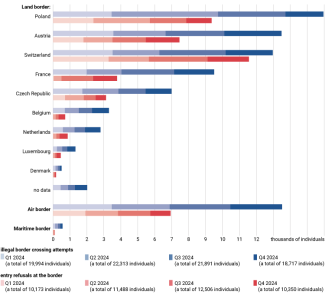

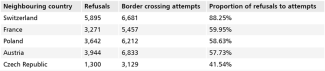

During coalition negotiations between the CDU, CSU, and SPD, the most contentious issue regarding migration policy concerned the possibility of implementing mass turnbacks of refugees at Germany’s border – a practice already effectively in place. In 2024, the Federal Police applied this measure to approximately 44,500 individuals – 28% more than in 2023. However, it is important to note that some individuals may appear multiple times in statistics on both entry refusals and illegal border crossings. In total, around 55% (based on the latest data from the second half of 2024) of migrants attempting to enter Germany illegally are forced to turn back – with the proportion at the Polish border reaching approximately 58%.

Chart 3. Illegal border crossing attempts recorded on Germany’s borders and entry refusals in 2024

Source: author’s own calculation based on figures compiled by the Federal Ministry of the Interior of Germany.

The increase in entry refusals is linked, among other things, to the practice of the Federal Police, who discourage individuals from applying for asylum in Germany by asking, for example, whether the person attempting to enter the country without the required documentation intends to take up employment. If the answer is affirmative, applying for asylum becomes impossible, effectively resulting in immediate refusal of entry. According to German media, highly complex forms were introduced several months ago, which migrants are required to complete at the border. Completing them often requires bringing in interpreters from distant Federal Police units, significantly prolonging the entire procedure. Additionally, officers are reportedly suggesting responses that are disadvantageous to the migrants, effectively excluding them from the possibility of submitting an asylum application.

Table. Refusals to enter Germany at selected borders in the second half of 2024

Source: author’s own calculation based on figures compiled by the Federal Ministry of the Interior of Germany.

Model cooperation with Switzerland

Germany views its border cooperation with Switzerland as exemplary and intends to develop similar forms of collaboration with its other neighbours. Since October 2023, Germany has issued approximately 15,000 entry refusal decisions at its border with Switzerland. Efforts to prevent illegal migration are supported by both a joint action plan (see Appendix) and the revised German-Swiss border cooperation agreement, which was amended on 5 April 2022.

The agreement significantly expands the powers of German authorities – for example, in comparison with those granted under the agreement with Poland dated 15 May 2014. Unlike the latter, the document signed with Switzerland allows German police to operate independently on Swiss territory in emergency situations – for surveillance, detentions, or searches, including outside official border crossings. Moreover, it permits operational decisions to be made at the local level without the need to obtain central approval each time. It also grants broader powers in the areas of data sharing and training, such as the automatic flow of information and the implementation of joint educational programmes.

In the event of a possible revision of the agreement with Poland and other neighbouring countries, Germany intends to treat the agreement with Switzerland as a model – particularly with regard to cross-border surveillance, unilateral actions, and the decentralisation of operational decision-making.

The clarification of the agreement and a list of specific measures for implementation are included in the joint German-Swiss action plan from 2022. The document is based on three pillars: police and border cooperation, legal aspects, and collaboration in migration policy. The two countries committed to intensifying joint border patrols, particularly in rail transport, and to conducting targeted operations against human smugglers. Plans also include enhancing the sharing of operational information between the two countries’ services and improving coordination of actions with neighbouring EU member states.

Effective border cooperation contributes to a reduction in the number of illegal migrants reaching Switzerland, partly by blocking new transit routes – primarily from Italy and France. In identifying detained individuals and implementing deportations, it is also helpful that Swiss authorities have access to certain EU data and analyses to which, as a non-EU country, they would not normally be entitled .

The CDU/CSU–SPD government’s migration policy outlook

Migration policy will be a priority for Germany’s incoming government, and further reductions in the number of asylum applications will largely determine the level of support for the new chancellor. Additional pressure to fulfil the commitments laid out in the coalition agreement will come from the anti-immigration AfD party, which is leading in some popularity polls. The importance of this issue – particularly border controls – is expected to grow further in 2026, ahead of regional elections in the eastern federal states of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Saxony-Anhalt, where the AfD stands a realistic chance of winning.

The proposals to tighten migration policy contained in the coalition agreement primarily concern:

- The border regime – maintaining permanent, random checks at all of Germany’s borders and the right to refuse entry (including for asylum seekers) ‘in coordination with neighbouring countries’.

- Improving the effectiveness of deportations – including efforts to increase the number of deportees by: exerting pressure on countries of origin to accept their citizens (such pressure could include, for example, limiting development aid, adjusting visa policies, or reducing economic cooperation), introducing permanent departure detention for individuals obliged to leave the country who pose a security threat, resuming deportations to Syria and Afghanistan, and expanding the list of so-called safe countries to include Algeria, India, Morocco, and Tunisia.

- Restrictions on benefits for refugees – including a reduction of approximately 100 euros per month in the allowance for Ukrainian refugees who submitted their applications after 1 April 2025; they will now receive support at the same level as other refugees, rather than an amount equivalent to the citizen’s benefit granted to Germans. Additionally, there are plans to provide this support in a cashless form (e.g. vouchers, prepaid cards).

- Ending voluntary immigration programmes – including those for refugees from Afghanistan – and abandoning any new initiatives of this kind. The agreement also provides for: a two-year suspension of the family reunification programme, the abolition – after 2027 – of the possibility of converting tolerated stay into permanent legal residence, a 50% reduction (to 25,000 individuals annually) in the quota of workers admitted under the so-called Balkan regulation, and the retention of the minimum five-year residency period required to obtain citizenship (eliminating the current shortened three-year procedure).

- The concept of so-called third countries – support at the EU level for the idea of recognising safe third countries as places where asylum applications can be processed and international protection provided.

Some of the proposed changes (such as expanding the list of safe countries) will require the approval of the Bundesrat, necessitating a compromise with the Greens, as the CDU/CSU and SPD do not hold a majority in the second chamber of the German parliament. This may weaken some of the Christian Democrats’ proposals and delay their implementation . Furthermore, a significant portion of migration policy responsibilities – such as providing accommodation, disbursing benefits, and carrying out deportations – falls within the competence of the federal states, which maintain diverse legal frameworks and practices in this area. However, the federal government will aim to improve coordination of migration policy conducted by local governments, federal states, and individual federal ministries (including the Interior Ministry, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development). A debate on centralising certain power – for example, in the area of deportations – is also to be expected.

The incoming CDU/CSU–SPD government will focus on border controls and maintaining a high rate of turnbacks at the border. At the same time, the nearly 50% year-on-year decrease in the number of asylum applications in Germany makes it harder to justify declaring a state of emergency under Article 72 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which would permit all migrants to be turned back directly at the border. The application of this provision is contentious, including among German legal experts, some of whom argue that the conditions for invoking it are not met (as current effective actions at the border are being carried out without reference to Article 72 TFEU). CDU politicians are aware that the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) may ultimately reject this legal justification. Nonetheless, they have so far relied on the likelihood that legal proceedings would be protracted, allowing Berlin to continue turning back migrants until the CJEU delivers a final verdict.

It is in Germany’s interest to enhance border cooperation – including with Poland – based on the Swiss model (e.g. by adopting a joint action plan). Sealing the EU’s external borders remains the long-term goal. Germany may also be interested in gaining support for the demands of EU border states regarding border reinforcement, including through the construction of barriers financed by EU funds. At the same time, Berlin will continue to advocate for a mechanism to distribute asylum seekers among member states based on a quota system. According to the German authorities, the fastest way to initiate relocations at present is through the EU Migration Pact, which the German government aims to implement as soon as possible.

In November 2024, Germany adopted a draft law to align specific national regulations with the principles of the EU Migration Pact. This includes, among other measures, a border procedure allowing asylum applications to be processed directly at airports and seaports – with clearly defined deadlines for decisions by authorities and courts. Germany will also press for the pact’s full adoption by the remaining EU member states. At the same time, it recognises the challenges associated with implementing the pact, and therefore plans to maintain its border controls until it is fully in force.

APPENDIX

Main points of the German-Swiss 2022 action plan to combat illegal migration

- Cross-border police cooperation

- Intensification of joint cross-border operations and control measures, particularly to combat organised human smuggling.

- Reinforcement of joint patrols, especially on cross-border rail routes.

- Both sides coordinate the operational planning of the Federal Police and the Federal Office for Customs and Border Security to ensure effective migration control and combat organised crime, regularly sharing information via established channels.

- Enhancing the coordination of border and police actions with other neighbouring countries affected by irregular migration, to agree on joint measures along the main migration routes.

- Expansion of existing communication channels for information sharing among border police at all levels.

- Increased communication (e.g. regular exchange of liaison officers and joint assessment of developments in the field of irregular migration) between the Federal Police and the Federal Office for Customs and Border Security in order to accelerate the exchange of operational information in the border area.

- Legal measures pertaining to migration

- Asylum seekers are promptly registered and preliminarily interviewed, with their fingerprints entered into the Eurodac system.

- Asylum seekers apprehended shortly after crossing the border are given priority placement in reception centres closest to the point of entry in the detaining country.

- In the case of asylum seekers who do not fall under the jurisdiction of the detaining country, the Dublin procedure is routinely initiated in order to transfer them to the competent country.

- Asylum procedures for nationals of countries with low recognition rates are prioritised and accelerated.

- Political cooperation in curbing illegal migration

- Germany and Switzerland support effective deportation procedures in European forums. Sanctions on visas and other appropriate measures at the level of the entire Schengen area should be applied to third countries that refuse to cooperate.

- Germany and Switzerland support countries on the Schengen periphery in fulfilling responsibilities related to external border protection, asylum procedures, refugee integration, and the return of rejected asylum seekers.

- Policy towards third countries

- Strengthening cooperation with countries of origin and transit through joint projects and initiatives in those countries, including:

- enforcing a consistent deportation policy;

- enhancing migration-related cooperation with third countries and increasing support for them;

- introducing measures to prevent irregular migration, particularly in the areas of border protection and combating smuggling and human trafficking.