A republic of seniors. Germany’s demographic challenges

Although Germany’s population is shrinking, the Federal Republic currently has the highest number of inhabitants in its history – nearly 84 million. According to moderately optimistic forecasts, its population will remain at a similar level until 2070. At the same time, a declining number of young people and a sharp rise in the share of senior citizens are transforming the country’s demographic structure in an unprecedented way. Germany is one of the oldest societies in the world – every second citizen is over 45 years old, and one in five is over 66. The consequences of an ageing population, such as labour shortage, challenges in maintaining the pension system, and the provision of care for the elderly, are being partially mitigated by the influx of migrants and their higher birth rate.

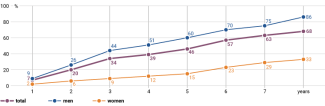

The price of these ongoing changes is a profound transformation of society – 30% of Germany’s population has a migration background, and the proportion of foreign nationals among school pupils exceeds 40%. This situation presents numerous challenges for the state and society – from increased spending on refugee integration and care, to a crisis in the education system, and tensions stemming from conflicts carried over from migrants’ countries of origin. Despite this, Germany remains convinced that the current level of prosperity can only be maintained through migration. According to data from the Institute for Employment Research (IAB) of the Federal Employment Agency, 86% of men who arrived in Germany in 2015–2016 have found employment. Demographic problems are particularly evident along the Polish border, as the eastern federal states are depopulating more rapidly, and the lack of immigrants – combined with an ageing population – is exacerbating the crisis. This situation is set to further intensify competition for workers with Poland and the Czech Republic.

A Mikrozensus conducted in 2022 is the source of most comprehensive statistics regarding Germany’s demographic situation.[1] In Germany, two types of censuses are conducted. The Zensus (‘large population census’) is conducted every ten years and serves to determine the official number of inhabitants at the national, federal state, and municipal levels, as well as to provide a detailed inventory of buildings and dwellings. The Mikrozensus (‘small population census’), on the other hand, is an annual survey covering a broader range of topics – it provides detailed information about the structure of society and the social and economic situation, and also enables the analysis of changes over time. The Zensus includes data from small municipalities, whereas the Mikrozensus – due to its smaller sample size – presents results only for larger administrative units, such as federal states or regions.

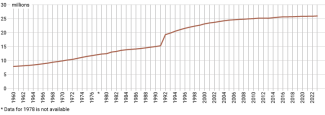

Germany has the largest population in its history

In 2024, around 83.6 million people lived in Germany – slightly more than in 2023, when the country’s population stood at 83.5 million. In 2022, due to the influx of refugees from Ukraine, Germany's population reached a record high of 84.5 million. At the same time, natural population growth has remained negative for years. In 2024, approximately 680,000 children were born, while about one million people died, resulting in a substantial birth deficit of around 320,000.[2] This marks the third consecutive year in which the figure has exceeded 300,000 – in 2023, it was 335,217, setting a new negative record. For comparison, between 1991 and 2021, the average annual birth deficit was 137,000.

Although the number of births stabilised over the past decade, between 2013 and 2022 767,000 (11.3%) more children were born than in the previous ten years. This increase occurred mainly between 2011 and 2016, when the fertility rate rose from 1.39 to 1.59. This was driven by improvements in social support for families (including the introduction of parental allowance in 2007 and its gradual expansion, as well as the development of childcare services in 2013) and by migration. Among mothers without German citizenship, the fertility rate in 2023 was 1.74, while among German mothers it was 1.26. The national average for that year was 1.35.[3]

In 2023, life expectancy at birth rose to 78.2 years for boys and 83 years for girls, and this upward trend is expected to continue. In analysing the country’s demographic development, the German Federal Statistical Office also prepares projections concerning the future of society. According to these forecasts, by 2070, life expectancy for men will increase by 4 to 8 years, and for women by 3 to 7 years.[4] This directly affects the ratio between the number of senior citizens (aged 65 and over) and people of working age (20–64), known as the old-age dependency ratio. A higher ratio places greater strain on the pension system and labour market. In Germany, this ratio stood at 37 in 2022, meaning that there were 37 senior citizens for every 100 people of working age. In this regard, Germany ranks second globally after Japan. In Europe, it is closely followed by Italy, Finland, and Greece, where the ratio has reached 36.

The scale of change becomes clear when today’s data is compared with the first post-Second World War figures. In 1950, the old-age dependency ratio was just 16. By the late 1970s, it had risen to 27, as a result of increasing life expectancy and the war’s demographic impact. During that period, the number of senior citizens increased by 5.5 million, while the number of people aged 20–64 grew by only 3.1 million. Between 1980 and 1991, the situation temporarily improved, as the ratio dropped to 24. This was due to the entry of the large post-war baby boomer cohorts into the workforce, and the retirement of the smaller generation born during the war. Since 1991, however, the trend has been clear – the ratio has steadily increased. A particularly notable phase occurred between 1998 and 2006, when the ratio jumped from 25 to 33 in just eight years. This was the result of increasingly smaller generations entering the labour market.

Migration as an opportunity

A scenario assuming a rise in the number of births is considered unrealistic for most highly developed societies, and Germany is no exception. Neither politicians nor experts regard the prospect of achieving a fertility rate of 2.1 – the level required to sustain population replacement – as feasible. Instead, hopes of mitigating the consequences of labour shortages and maintaining prosperity in Germany rest on migration, which has repeatedly improved the country’s demographic situation and served as a reservoir of labour in the past.

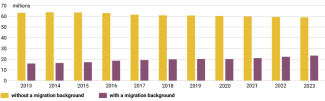

Chart 1. Germany’s population with and without a migration background in 2013–2023

Source: author’s own calculation based on figures compiled by the German Federal Statistical Office.

Since German reunification up to the beginning of 2024, net migration amounted to approximately 11.3 million people, of whom around 600,000 held German passports and about 10.7 million were foreign nationals. Except for the years 2008 (-56,000) and 2009 (-13,000), the migration balance has always been positive. Around a third of the total growth occurred between 1991 and 2003. After a slowdown from 2004 to 2009, the net migration figure began to rise again, reaching 1,139,000 in 2015. In 2022, the highest net migration figure since 1950 was recorded – 1,462,000 individuals. In response to these developments, Germany amended its citizenship law in 2024, reducing the required period for naturalisation from eight to five years, and to as little as three years in cases of particularly rapid integration. The new regulations also allow for dual citizenship, subject to conditions such as German language proficiency at B1 certificate level, no record of serious criminal offences, and the ability to support oneself independently.

The key question regarding migration as a means of improving the labour market situation concerns the proportion of refugees who found employment after arriving in Germany and the time it took them to transition from the social welfare system to the labour market. Among those who arrived in 2015, fewer than 10% were employed in their first year after settling. After six years, this figure rose to 57%, after seven years to 63%, and after eight years to 68%. Among men, the employment rate after eight years reached 86%, while among women it was only 33% (for comparison, the average employment rate in Germany is 81% for men and 72% for women). Despite improvements in employment, a significant – though rapidly declining – reliance on social welfare benefits among refugees remains visible. While in 2016 as many as 89% received social welfare support, by 2022 this share had decreased to 39%.[5]

Chart 2. Proportion of employed refugees according to gender and length of stay in Germany

Source: author’s own analysis based on figures compiled by IAB.

Multiculturalism as a norm

Germany is now a multicultural country – 30% of its population has a migration background. In 2023, this accounted for 24.9 million individuals who were either not born German citizens themselves or had at least one parent who was not a citizen of Germany by birth. This group includes both immigrants and their children born in Germany, as well as individuals who acquired German citizenship after arriving in the country, and (late) resettlers from the former USSR and their descendants. The majority of newcomers (58%) still hold foreign citizenship, but as many as 42% have already obtained German passports. Among this group, 76% are first-generation migrants, while 24% are their children born in Germany.[6]

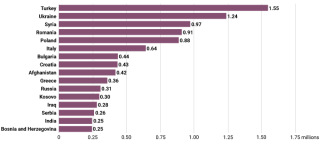

The scale of migration becomes even more apparent when looking at the number of people residing in Germany without German citizenship. In 2022, this group numbered 12.3 million, representing 15% of the population. Most of them came from Europe (69%) and Asia (21%). The largest groups were Turks (12%), Ukrainians (10%), Syrians (8%), Romanians (8%), and Poles (7%). At the same time, it is important to note that official statistics do not include all migrants. Expellees from the Second World War period (Vertriebene) have a separate legal status and are not included in this category.[7]

Chart 3. Number of foreigners from specific countries residing in Germany (as at 31 December 2023)

Source: author’s own calculation based on figures available at statista.com.

As with foreign nationals living in Germany, Europe is also the main source region for people with a migration background residing in the country: 65% of these individuals (13.7 million) originate from countries on the European continent. At the same time, the number of individuals from other parts of the world, especially the Middle East and Africa, is increasing. In 2023, 4.1 million had roots in the Middle and Near East (19% of the population with a migration background), and 1.1 million had ties to Africa.

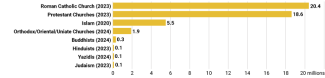

Chart 4. Number of members of specific religious communities in Germany

Source: author’s own calculation based on figures compiled by the German Federal Statistical Office.

All children are ours

People with a migration background are, on average, younger than the rest of the population – their median age is 38, which is nine years younger than that of other Germans (47). They are also more likely to have children. This is clearly evident in educational institutions, where changes in the ethnic composition are particularly noticeable. According to the 2023 Microzensus, 41.6% of pupils in general and vocational schools in Germany had a migration background (2022 – 41.3%; 2021 – 39%).[8] In the 2024/2025 school year, out of approximately 11.4 million pupils, 1.9 million – or 16% – held foreign citizenship. Compared with the previous year, this figure increased by 6% (in contrast, the number of children with German citizenship rose by only 0.4% in 2023).

Almost half of Germany’s youngest children have a migration background. In 2023, 2.1 million children under the age of six came from such families – accounting for 43% of all children in that age group. This proportion is rising – in 2011, it was 33%. This trend is particularly evident in nurseries. In Hamburg, where the rate is among the highest, children of foreign descent already make up the majority – 51%. A similar pattern can be observed in kindergartens: in 2007, the share of migrant children among attendees was 23%; today, it is nearly 30%.

The proportion of children with foreign citizenship varies by region, revealing clear differences between eastern and western Germany. The highest share is recorded in Bremen, where they account for as much as 67% of all residents under the age of six, while the lowest is in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania – only 18.5%. Other eastern federal states such as Brandenburg (21.3%), Saxony (20%), and Thuringia (22%) also show relatively low shares. In contrast, the situation in western Germany is markedly different: after Bremen, the highest numbers of migrant children are found in Berlin (57%) and Hesse (54%), with the lowest in Schleswig-Holstein (35%).[9]

The situation is similar in schools. In Hamburg, during the 2024/2025 school year, an average of 54.5% of pupils have a migration background. The highest proportions are found in district schools (62.5%)[10] and preschool classes (62.2%), followed by primary schools (53.4%), with the lowest in grammar schools (45%). The growing number of children with foreign citizenship presents new challenges for the education system, particularly in teaching the German language, promoting cultural integration, and addressing differing understandings of history – especially regarding the Holocaust and Germany’s responsibility for the crimes of the Second World War.[11]

Germany’s east is experiencing depopulation and radicalisation, while its west is rejuvenating

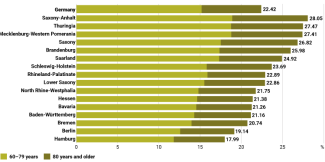

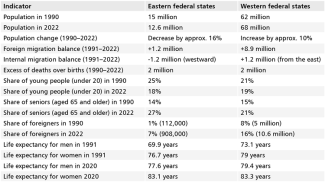

Although 35 years have passed since Germany’s reunification, the divide between its east and west remains clearly perceptible – particularly in the area of demography. Shortly after 1990, the eastern federal states experienced a wave of emigration, mainly of young people – especially women – in search of better living conditions in the west. Consequently, the population of the former GDR shrank rapidly, and the ageing of society accelerated. In contrast, former West Germany attracted new residents – from the east and, for many decades, from abroad. This helped the west age more slowly, while the proportion of people with a migration background steadily increased. The effects are still visible today: eastern federal states have fewer citizens and a higher share of senior citizens, while western federal states are younger and more ethnically diverse.

Since 1990, the eastern federal states have lost around 2.4 million inhabitants. This was mainly due to negative net migration – approximately 3.7 million individuals moved to western Germany – as well as lower birth rates. Consequently, the former GDR regions are not only more sparsely populated, as already mentioned, but also significantly older. The share of residents over the age of 65 in the east stands at 27%, compared to 21% in the former West Germany. Additionally, the migration of more young women than men reduced the population of women of reproductive age, which negatively impacted the number of births.

In unified Germany, 25.4 million children have been born, of whom only 3.4 million – or 13% – were born in the eastern federal states. In the early 1990s, during a period of sharp decline in birth rates, only one in ten citizens of the newly unified country was born in the east. The fertility rate in the former GDR reached its lowest post-reunification level between 1993 and 1994, falling to just 0.77. It was only from the mid-2000s onwards that fertility rates in the east and west began to converge.

The federal states still differ significantly in terms of childlessness. In 2022, 20% of women aged 45–49 in the western states had no children, compared with only 14% in the eastern ones.[12] Although childlessness increased more rapidly in the east after reunification, it remains lower. This is due to ideological differences. The GDR supported women in combining motherhood with employment through widespread availability of nurseries, flexible working hours, and family-oriented policies. In contrast, West Germany followed a more conservative model, in which women often had to choose between a career and motherhood. The lack of developed childcare services meant that many women opted not to have children, as they were unable to balance child-rearing with professional responsibilities. After 1990, the situation in the east changed – the dismantling of some of this support and labour market uncertainty led to a rise in childlessness. However, these states still stand out for their better access to childcare and higher employment rates among mothers, which continue to encourage parenthood.

Chart 5. Proportion of residents aged 60 and older in individual federal states in 2023

Source: author’s own calculation based on figures compiled by the German Federal Statistical Office.

Between 2017 and 2022, the migration trend reversed – more people moved from the western to the eastern federal states than in the opposite direction, resulting in a small positive net internal migration balance for the east (+18,000 individuals). This process is confirmed by projections for cities such as Dresden and Leipzig. Forecasts indicate that the population of Dresden will grow from 554,000 in 2018 to approximately 587,000 by 2035 – an increase of 6% in the most optimistic scenario. The trend is even more pronounced in Leipzig, where the population is expected to rise from 587,000 in 2018 to around 681,000 by 2035 – a 16% increase at best.[13] Both cities are attractive due to their dynamic economic development, new investments, and the presence of federal and state administrative offices as well as media outlets, including the regional public broadcaster MDR. Most importantly, they are major academic centres. An additional advantage – particularly for Leipzig – is its proximity to Berlin and strong transport links with the capital.[14]

Depopulation and changes in the social structure are increasingly influencing the political preferences of residents in the eastern German federal states. The AfD performs worse in districts with higher average incomes and education levels, and better in areas characterised by older populations and higher unemployment.[15] Men are more likely to vote for the party – in the Landtag election in September 2024, 35% of male voters supported the AfD, compared with 25% of female voters. Among senior citizens, the CDU enjoys greater popularity. In Saxony, the party received 42% of the vote among those aged 60 and older, but only 15% among people under the age of 30. Strong support from the oldest, most numerous, and most politically active segment of the population enabled the CDU to win yet another election in that federal state.[16]

The demographic profile of the former West German territories is markedly different. From the mid-1950s onwards, these areas saw the arrival of economic migrants – the so-called Gastarbeiter. Between 1955 and 1968, West Germany signed agreements with eight countries (the first with Italy, and the most significant with Turkey in 1961), resulting in the arrival of around 14 million foreign nationals, of whom approximately 11 million later returned to their countries of origin.[17] These migrants permanently altered the demographic landscape of the country, contributing to population growth, a younger age structure, and higher birth rates. They also paved the way for future generations of immigrants while simultaneously introducing some ethnic tensions into Germany.[18] The Gastarbeiter played a crucial role in enabling West Germany’s dynamic economic growth during the 1950s and 1960s. After 1989, the western federal states were further strengthened by the influx of young and highly educated Germans from the former GDR. Consequently, the so-called old federal states of West Germany recorded a positive internal migration balance of 1.2 million individuals.

Table. Comparison of selected demographic indicators in eastern and western federal states

Source: author’s own calculation based on figures compiled by the German Federal Statistical Office, destatis.de.

More pensioners, fewer working individuals

The German debate on demography focuses primarily on an ageing population and the projected decline in the number of working-age individuals, along with the consequences of these trends for the labour market, the economy, and the pension and care systems. Secondary concerns include ensuring equal access to public services across all regions (especially in rural areas), challenges in the education system, and the approach to migrant integration. Issues such as pension levels, working hours, and social security contribution rates also remain among the most significant topics during Bundestag election campaigns.

There is a broad consensus that the shortage of labour is the greatest long-term structural challenge facing Germany. Currently, there are around 1.5 million job vacancies nationwide. This problem is expected to worsen, as the baby boomer generation of the 1960s enters retirement. Each year, around 400,000 individuals leave the labour market. According to estimates by the Institute for Employment Research (IAB), the gap could grow to as many as 7 million workers by 2035.[19] This issue affects all sectors and is not limited to highly qualified professionals. Staffing shortages not only hinder business development but also impede reforms in education, refugee integration, and health care. Moreover, they pose an existential threat to the economy. While automation and digitisation of the labour market could improve the situation, these areas have so far been a weak point for both business and public administration. Consequently, recruiting workers from abroad remains the primary solution.[20]

For years, Berlin has pursued a three-pronged strategy aimed at addressing labour shortages: increasing the involvement of the domestic workforce (e.g. through reform of the social welfare system to encourage unemployed individuals to take up employment), recruiting workers from the EU, and relaxing regulations to facilitate the entry of qualified professionals from third countries (outside the EU, the European Economic Area, and Switzerland). However, previous measures – such as the so-called Migration Package of 2019 – did not lead to significant improvements in this area. Further liberalisation of labour immigration included initiatives implemented prior to the Russian-Ukrainian war, such as simplified procedures for Ukrainians and, above all, a coalition initiative by the SPD, the Greens, and the FDP to make it easier for foreigners to find employment. Reforms encompassed both the simplification of procedures for individuals already residing in Germany under tolerated status (Duldung), and the creation of a points-based system modelled on the Canadian framework. The new regulations, especially those encouraging legal labour immigration, are intended to bridge the workforce gap and at the same time restore governmental control over the influx of foreigners. So far, however, Germany has not been a particularly attractive destination for workers from outside the EU. This has been due to several factors, including the language barrier, excessive bureaucracy, underdeveloped digital infrastructure, complex procedures for recognising foreign qualifications, and the national tax system.

The situation is further exacerbated by the fact that fewer and fewer young people are entering the labour market. At the same time, the growing number of pensioners and the increasing duration of retirement mean that the stability of the pension system is one of the most pressing challenges facing Berlin. In 2022, the average retirement duration was approximately 18.8 years for men and 22.2 years for women. To mitigate the effects of an ageing population, some benefits have been abolished, and the retirement age is being gradually raised. It is currently set at 67 years, but these rules will not be fully implemented until 2031 – until then, numerous exemptions apply, and the period of working life continues to be extended. The reform was passed in 2007 and has sparked major controversy over the years. Despite the equalisation and increase in the retirement age, the system still requires subsidies from public funds.

Chart 6. Average retirement duration for Germans ( 1972–2022)

Source: ‘Rentenatlas 2023’, Deutsche Rentenversicherung, deutsche-rentenversicherung.de.

The German pension system is based on a pay-as-you-go model – current workers finance benefits for retirees. At present, the ratio of contributors to pensioners is 2:1, meaning there are two working individuals for every retiree. However, by 2050 this ratio could fall to 1.5:1, placing significant strain on the system. Pensions account for approximately 30% of public spending – in 2023, this expenditure amounted to €325 billion. To cover the shortfall, the federal budget contributes approximately €100 billion annually to the pension fund.[21]

Avoiding the need to reduce benefit levels and ensuring the stability of the system in the face of an ageing population remains the overarching political objective in the debate on this issue. The most frequently discussed reform proposals – both from politicians and experts – include raising the retirement age to 70, increasing social security contribution rates (currently standing at 18.6% of gross wages, split equally between employee and employer), and introducing additional taxation on capital gains.

Chart 7. Number of pensioners in Germany, 1960–2023

Source: author’s own calculation based on figures compiled by the German Federal Statistical Office.

An ageing German population presents challenges not only for the pension system but also for the care services sector. Currently, around 5.5 million individuals in Germany require long-term care – nearly double the number from the late 1990s.[22] By 2050, this figure could rise to between 7 and 7.5 million. The care sector currently employs approximately 1.7 million individuals, but it is estimated that by 2034 the staffing gap could widen to 350,000, and by 2049 – to as many as 690,000 workers.[23]

Employment of foreign nationals in care professions increased at an above-average rate between 2013 and 2023. In the elderly care sector, the number of foreign workers rose by 273%, equating to nearly 87,000 individuals. A significant increase was also recorded in hospital care, with a 256% rise, or 109,000 additional workers. Over the course of a decade, the share of foreigners among all employees in this field grew from 4.9% to 14.5%. In professions related specifically to elderly care, their proportion reached 18.9% in 2023 – an increase of 12 percentage points compared with 2013.[24]

Germany is actively pursuing a policy of recruiting care workers from other countries – particularly from South America and Asia – as the potential for hiring staff within the EU and the Balkans is now significantly limited. For example, under a partnership with the Philippines, several hundred qualified care workers migrate to Germany each year under special programmes. Similar pilot projects are in place with Mexico and other Latin American countries. One of the main challenges for non-EU foreigners seeking employment in this sector is the complex, lengthy, and time-consuming process of training and diploma recognition. The requirement to learn the German language is another barrier. At the same time, steps are being taken to increase the number of workers, such as raising wages and improving working conditions, though these measures significantly drive up the cost of care. In 2022, expenditure on long-term care totalled around €55 billion, of which over €40 billion came from the mandatory long-term care insurance (Pflegeversicherung). A stay in a care home costs approximately €2,000 to €2,500 per month, and residents – despite being insured – must pay between €700 and €1,200 out of pocket.

Outlook

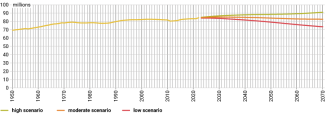

Germany will remain the most populous country in the European Union, but unlike France, which has a higher fertility rate (1.68 vs. 1.35; the figure for Poland is 1.16), it will need to rely more heavily on immigration. Long-term demographic forecasts outline three possible development paths for Germany:[25]

- moderate scenario – assuming moderate fertility and life expectancy, along with an average net migration balance of 290,000 individuals annually, the population will rise to 85 million by 2031, and then decline to 83 million by 2070;

- low scenario – with a low net migration balance (180,000 individuals annually), the population will shrink to 75 million by 2070;

- high scenario – with a high net migration balance (400,000 individuals annually), the population will increase to 90 million by 2070.

Chart 8. Demographic forecasts for Germany’s population from 2023 until 2070

Source: author’s own calculation based on figures compiled by the Federal Institute for Population Research.

By the mid-2030s, the number of people of retirement age – those aged 67 and older – will increase from 16.4 million to at least 20 million. The group aged over 80 will remain relatively stable, between 5.8 and 6.7 million, until around 2035, but will then rise significantly, intensifying the demand for long-term care. At the same time, the population aged 20 to 66, which currently numbers 51.4 million individuals, will shrink. With high net migration, this figure will decrease by 1.6 million by the mid-2030s, whereas with low net migration, it could fall by as much as 4.8 million.

Challenges

- An ageing population and the lack of generational replacement will become an increasing burden on Germany’s public finances. Ensuring a high standard of living for senior citizens – including adequate pensions, an efficient health care system, and access to well-developed care services – will become one of the top priorities for future governments. At the same time, spending in this area will compete with other budgetary demands, especially if there is no significant economic growth. However, seniors remain the largest and most disciplined group of voters, which will ensure that their interests continue to hold a central place in German politics.

- The share of people with a migration background in society will continue to grow. This is due both to the conviction that immigration represents a key tool for mitigating the negative effects of demographic change and to the higher birth rates within this group. This process may lead to increased tensions between long-standing residents and newcomers,[26] particularly regarding the distribution of resources – migrants are statistically poorer, have worse living conditions, and receive lower pensions. Additionally, ethnic conflicts from migrants’ countries of origin may spill over into Germany, along with disputes over issues such as the interpretation of German history. In this context, education reform – including substantial increases in funding and partial centralisation (as education is currently the responsibility of the federal states) – as well as the formal recognition of Germany as an immigration country, will be crucial for accelerating the integration of new citizens.

- The biggest demographic challenges facing Germany will vary by region. In the west, the main issue will be the rising proportion of senior citizens, while in the east, the shrinking working-age population will pose the greatest concern. The population in the western federal states is likely to stabilise, whereas in the eastern states – particularly in regions bordering Poland – it is expected to continue declining. In contrast, major cities such as Berlin, Hamburg, Leipzig, and Potsdam are projected to see population growth.

- Improving living conditions in less urbanised areas is one of the most pressing challenges Germany is facing. Expanding access to public services – particularly in health care, elderly care, and education – creating well-paid jobs, and enhancing overall quality of life are critical priorities in regional policy, especially in rural regions. Improving living standards, including access to housing and lower living costs in smaller towns, aims to slow the outflow of young people to major cities and encourage their return after completing their education. Rural depopulation, particularly in the eastern federal states, contributes to political radicalisation and rising support for extremist parties.

- In the areas bordering Poland, labour shortages on both sides of the border will lead to increasingly intense competition for workers. One manifestation of this trend was the introduction, during the COVID-19 pandemic, of special allowances for individuals commuting daily from Poland to Germany – particularly to manufacturing plants or the healthcare sector – to enable them to stay temporarily in Germany. Similar competition may arise concerning Poles working in other sectors, and current economic migration could further reinforce this trend – especially in the care and medical sectors. It is estimated that in 2023, nearly one in four care workers in Germany was from Poland, with women accounting for over 90% of Polish care personnel.[27] Additionally, Germany may become an attractive employer for economic migrants residing in Poland, including Ukrainians and Belarusians.

[1] ‘Mikrozensus 2022’, German Federal Statistical Office, Wiesbaden 2023, destatis.de.

[2] ‘Bevölkerung im Jahr 2024 um 100 000 Menschen gewachsen’, German Federal Statistical Office, 23 January 2025, destatis.de.

[3] ‘Geburtenziffer 2023 auf 1,35 Kinder je Frau gesunken’, German Federal Statistical Office, 17 July 2024, destatis.de.

[4] ‘15. koordinierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung’, German Federal Statistical Office, destatis.de.

[5] H. Brücker, M. Ehab, P. Jaschke, Y. Kosyakova, ‘Arbeitsmarktintegration von Geflüchteten: Verbesserte institutionelle Rahmenbedingungen fördern die Erwerbstätigkeit’, IAB, October 2024, doku.iab.de.

[6] ‘Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund’, German Federal Statistical Office, destatis.de.

[7] ‘Migrationshintergrund’, German Federal Statistical Office, 2 February 2025, destatis.de.

[8] Nationwide school statistics do not include standardised figures on students’ ethnic background. Although the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK) resolved in 2005 to include ‘migration background’ in the statistics, only selected federal states have implemented this decision to date. Moreover, in these federal states, ethnic background is recorded according to differing criteria.

[9] ‘Wie viele Kinder in der Kita haben einen Migrationshintergrund?’, Mediendienst Integration, January 2025, mediendienst-integration.de.

[10] District schools offer a flexible option for students who chose not to follow the university-oriented path typical of grammar school pupils, but instead prefer to take their final exams (Abitur) at a later stage or to complete their education at a lower level. Thus, these schools often serve pupils from more diverse social and educational backgrounds.

[11] For more on educational and practical challenges and potential conflicts arising from the growing number of migrants in schools see K. Frymark, Between hope and illusion. Germany’s migration policy, OSW, Warszawa 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[12] ‘Bevölkerungsentwicklung in Ost- und Westdeutschland zwischen 1990 und 2023: Angleichung oder Verfestigung der Unterschiede?’, German Federal Statistical Office, destatis.de.

[13] ‘7. Regionalisierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung für den Freistaat Sachsen 2019 bis 2035’, Statistical Office of the Free State of Saxony, 2020, demografie-portal.de.

[14] K. Frymark, The Free State of Saxony. The state of permanent transformation, OSW, Warszawa 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[15] C. Franz et al., ‘Wirtschaft, Demografie und strukturelle Missstände: Die Faktoren hinter dem Erfolg der AfD bei der Europawahl 2024’, DIW Wochenbericht, no. 34/2024, DIW Berlin, diw.de.

[16] K. Frymark, ‘Success for the AfD and the BSW in Thuringia and Saxony’, OSW, 2 September 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[17] ‘Erstes Anwerbeabkommen vor 65 Jahren’, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (bpb), 17 December 2020, bpb.de.

[18] K. Frymark, Between hope and illusion…, op. cit.

[19] T. Hellwagner et al., ‘Wie sich eine demografisch bedingte Schrumpfung des Arbeitsmarkts noch abwenden lässt’, IAB-Forum, 21 November 2022, iab-forum.de.

[20] K. Frymark, Between hope and illusion…, op. cit.

[21] ‘Gesetzliche Rentenversicherung’, Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, 11 February 2025, bmas.de.

[23] ‘Bis 2049 werden voraussichtlich mindestens 280 000 zusätzliche Pflegekräfte benötigt’, German Federal Statistical Office, 24 January 2024, destatis.de.

[24] ‘Das Beschäftigungswachstum in der Pflege wird inzwischen ausschließlich von ausländischen Beschäftigten getragen’, Institute for Employment Research, 15 October 2024, iab.de.

[25] ‘15. koordinierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung’, German Federal Statistical Office, destatis.de.

[26] A. Kwiatkowska, Strangers like us. Germans in the search for a new identity, OSW, Warszawa 2020, osw.waw.pl.

[27] M. Propson-Hauck, ‘Für die Pflege nach Deutschland’, Deutschland.de, 17 May 2023.