Neighbourly feuds. The problem with Ukrainian grain on the Central European markets

Since the EU decided in June 2022 to temporarily lift customs duties on Ukrainian imports, including agri-food imports, the sudden inflow of grain from Ukraine has become increasingly problematic for Central European countries. In May this year the European Commission imposed temporary restrictions on the import of four agricultural products from this country (wheat, corn, rapeseed and sunflower seeds). The restrictions were lifted on 15 September. Since then, the Central European countries have been looking for ways to resolve the problem on their own, which has further strained relations between them and Kyiv. Poland, Hungary and Slovakia implemented unilateral restrictions, Romania agreed with Ukraine to temporarily suspend imports, and Bulgaria banned imports of sunflower seeds under pressure from farmers’ protests.

Agri-food products account for around 60% of Ukraine’s exports, and the EU member states located closest to Ukraine have become an important sales market for it since the outbreak of the war and the EU’s abolition of customs duties on Ukrainian goods. Kyiv is determined to get the import ban lifted, first of all because it has limited logistic options to export goods after Russia withdrew from the grain deal in mid-July 2023 and the route from Ukrainian Black Sea ports was blocked again. Ukraine will continue to make efforts so that all restrictions on the sale of its agricultural produce to neighbouring countries are abolished. However, unless an effective mechanism is developed to regulate grain imports, this issue will still have a negative impact on Ukraine’s relations with these countries – countries which, for the most part, have been among the EU’s strongest advocates of political, military and economic support for Kyiv.

Ukrainian agricultural exports after 24 February 2022

Foreign sales of agricultural production have been adversely affected by the war (-15.5% in 2022), though much less than exports overall (-35%). Ukrainian agriculture is very much export-oriented: the harvests of the main cereals (wheat and corn) are several times higher than domestic consumption levels. Moreover, agri-food products are Ukraine’s most important export product: between January and September this year they accounted for over 60% of goods exported. Before Russia’s full-scale invasion, Kyiv used to send as much as 90% of its agricultural exports through the Black Sea ports. The invaders blocked this route already on 24 February 2022, which forced Ukraine to start developing routes via the ports on the Danube, as well as via the road and rail routes connecting it with the EU. However, this has only partially solved the problem.

The so-called Black Sea Corridor[1] started operating in August 2022; it enables exports of a total of 32.9 million tonnes of agricultural production from Ukrainian seaports (58% corn and 27% wheat), including 16.7 million tonnes to the EU. However, Russia withdrew from the deal on 17 July this year,[2] and the problems with grain exports reappeared.

In June 2022, the EU made an unprecedented decision to temporarily lift customs duties on Ukrainian exports, including agricultural products, which de facto opened the EU market to goods from this country. Agricultural products began to flow primarily to the member states neighbouring Ukraine. Exporting such goods by land is most profitable to Kyiv when they reach the markets closest to Ukrainian territory. In the case of sales to EU countries located further away, transport costs increase significantly, profits drop and the business becomes less and less cost-effective.

In terms of volumes, cereals (corn and wheat) and oilseeds (rapeseed and sunflower) had the largest share in Ukrainian exports. From February 2022 to May 2023, a total of 29.5 million tonnes of these four products entered the EU by sea, river, rail and road; as much as 11.3 million tonnes (38.3%) of these were supplied to five Central European countries, including 3.93 million tonnes (13.3%) to Poland. As a consequence of the inflow of Ukrainian products, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria began complaining about unfair competition, especially since they had imported almost no grain from this country before the invasion.

EU embargo on imports of four agricultural products

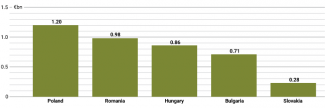

The competition became ever more intense. From February 2022 to May 2023, Ukraine supplied corn, rapeseed, wheat and sunflower seeds worth €10.2 billion to the EU. The value of these products exported to the five Central European countries stood at €4.03 billion (39.5%), including €1.2 billion (11.8%) to Poland.

Chart 1. Value of Ukrainian exports of corn, rapeseed, wheat and sunflower seeds to Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria from February 2022 to May 2023

Source: Eurostat.

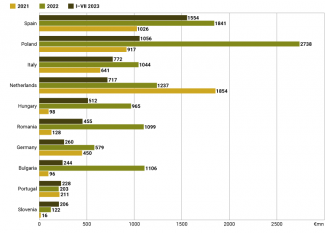

On 2 May 2023, the EU introduced a ban until 15 September on imports of corn, wheat, rapeseed and sunflower seeds from Ukraine to Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria under pressure from these countries’ governments. However, the restrictions did not affect all agricultural exports or transit. The change in the geographical structure of Ukrainian sales to customers in the EU is illustrated in Chart 2. While before the outbreak of the war, Poland was the only important market for agri-food production from Ukraine among its EU neighbours, in 2022 and 2023 all the countries bordering Ukraine and Bulgaria increased their imports by factors of several, Hungary by almost 10. They thus overtook the levels of imports from those Western European countries which had been the most important recipients of Ukrainian agricultural produce before the Russian invasion.

Chart 2. Comparison of the value of Ukrainian agri-food exports to the 10 main EU recipients in 2021–2023

Source: Eurostat.

In search of new export routes

The ban was coupled with fundamental changes in the targets for sales of Ukrainian agricultural products. Since the beginning of the war Ukrainian ports on the Danube, which had previously played a marginal role, gradually gained in importance thanks to the joint efforts of Kyiv and Bucharest. Whereas in March 2022, food exports via this route stood at only 55,000 tonnes, in June of 2023 they exceeded 1 million tonnes, and around 2.3 million tonnes of agricultural produce were being shipped monthly in August and September. According to the Ukrainian infrastructure minister Oleksandr Kubrakov, the declared goal is to achieve an annual throughput of 30 million tonnes.[3]

Moreover, after Russia withdrew from the grain corridor deal, Ukraine decided to launch an alternative route from the Black Sea ports, running along its coastline towards the territorial waters of Romania. Initially, five ships that had been blocked since the beginning of the war used it, but between 16 September and 16 October, 31 vessels with a total capacity of 1.3 million tonnes sailed the new route. This new route has enabled the transport not only of agricultural produce, but also of metallurgical production and ores, the export of which by sea has been impossible since 24 February 2022. The proportion of goods sent along this route has not been revealed so far. However, if 1 million tonnes of food monthly are transported along this corridor and the remaining routes are maintained, this should be enough to cover Ukrainian export demand, which is currently estimated at 4.8 million tonnes per month.

However, the safety of the new route and, more broadly, of the ports’ infrastructure, remains debatable. According to Kubrakov, since Russia terminated the grain agreement it has carried out 17 mass-scale attacks with drones and missiles on the ports, including Izmail and Reni; this has reduced their export potential by 40% and destroyed 300,000 tonnes of grain. Ukrainian military intelligence has also reported that Russia intends to plant sea mines on the routes used by ships transporting Ukrainian grain.

On 10 October, President Volodymyr Zelensky announced the planned launch of a railway grain corridor leading from Ukraine through Moldova (including separatist Transnistria) to the Moldovan port of Giurgiulești and the Romanian port of Galați. Customs clearance will reportedly take place at the joint Ukrainian-Moldovan checkpoint in Kuchurhan (on 13 October, Kyiv and Chișinău signed an agreement to this effect). This is the second rail connection between Ukraine and Moldova which has been established since the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian war. Earlier, in August 2022, a revitalised section of the Berezyne-Basarabeasca route connecting the Moldovan railway network with the Ukrainian port of Izmail was put into operation; it allows the transport of around 12,000 tonnes of goods per day.

Apart from the sea, the land route (previously almost unused) has gained great importance since the invasion. From 24 February 2022 to September 2023, Ukraine managed to export nearly 23 million tonnes of cereals, oilseeds, oils and oil cake in this way. The imposition of the EU ban led to a significant reduction in foreign sales via rail (it fell 40% compared to March this year) and road transport (-60%). However, the decrease was temporary: since transit through these countries was not prohibited, the exports were redirected and went to other EU member states. In August and September, the volume of food transport by land (across the borders with EU member states and Moldova) began to increase; road transport rose from 186,000 tonnes in May to nearly 250,000 tonnes in September, and in the case of rail transport it reached a level similar to that before May (almost 1 million tonnes).

The transit of Ukrainian grain through Poland by land (road and rail) reached 114,000 tonnes in January this year, and 260,000 tonnes in June (more recent data are not available). However, there is a problem with the technical throughput of the infrastructure on the Polish-Ukrainian border, which is lower than it could be due to the difference in rail gauges between the two countries.

Lithuania is interested in exporting Ukrainian grain, and to this end it would like to use the port in Klaipėda, which is currently operating at only 60% of its potential capacity. On 3 October, the agriculture ministers of Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine agreed that phytosanitary and veterinary control of agricultural cargo arriving at Lithuanian ports would be transferred to Klaipėda. This is intended to streamline transit and boost its volume. However, since global grain prices have been low for quite a while the viability of this solution is debatable, given the high transport costs. To improve matters, Poland has supported the idea that the EU should subsidise the transport of Ukrainian grain; this suggestion was put forward by the European Commissioner for Agriculture, Janusz Wojciechowski. However, it is currently unclear when, or even if, such a mechanism could be put into operation.

Lifting the EU embargo: reactions country by country

On 15 September, the European Commission decided not to extend the restrictions on imports of corn, rapeseed, wheat and sunflower seeds from Ukraine to the above-mentioned five Central European countries that had been in force since 2 May this year. On the same day, Poland, Slovakia and Hungary unilaterally imposed their own bans, which came into operation on 16 September. Hungary expanded the embargo to a total of 25 agricultural products, and Poland did the same to wheat flour, bran and oil cake. A few days earlier, Bulgaria announced that it would not support extending the restrictions, but after a few days later it changed its mind and banned the import of additional agri-food products. Romania appealed to the European Commission to extend the ban, but it has not officially implemented it unilaterally.

In response to these moves, Kyiv initiated dispute complaints at the WTO against Poland, Slovakia and Hungary, and threatened it would impose an embargo on the import of certain fruit and vegetables from Poland. At the same time, after consulting the European Commission, Ukraine put forward proposals to limit the sales of wheat, corn, rapeseed and sunflower to the five countries in question as part of a licensing system. At the same time, all these countries adopted their own solutions to limit or suspend grain imports from Ukraine.

Romania and Ukraine agreed on 20 September to introduce a bilateral licensing system, which was finally approved by the Romanian government on 12 October. From the moment the European Commission lifted the restrictions on grain imports to the EU until the above-mentioned system comes into force, Ukraine has undertaken not to put forward any applications regarding grain exports. According to the special provisions approved by the Romanian government regulating the import of Ukrainian grain (wheat, corn, sunflower seeds and rapeseed), only farmers (primarily breeders) and processors can be recipients of this category of goods, and not intermediaries. This restriction is intended to curb grain speculation and transfers onto the black market. Import licences can only be granted to Romanian entities which can prove that their own reserves are insufficient to meet their needs.

In accordance with the adopted legislation, each company that is interested in Ukrainian grain and meets the above requirements must apply each time for a license from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Romania, on the basis of an opinion prepared by a commission appointed by the ministry (members of which include representatives of the fiscal and customs services and the National Sanitary Veterinary and Food Safety Authority). This body, in turn, will prepare the opinion based on an analysis of the prospective importer’s situation and the quality of the samples of grain imported from Ukraine provided by it (the buyer is obliged to obtain a certificate of grain quality issued by the Romanian National Sanitary Veterinary and Food Safety Authority, NSVFSA).

Bulgaria banned the import of sunflower seeds from Ukraine (these account for over 90% of the import of the four goods in question) under pressure from mass protests by farmers. Formally the ban began on 1 October, but in reality it had been operating since mid-September. The embargo is scheduled to last until the end of November. Until then, imports of milk powder, honey and frozen raspberries will also be suspended.

On 29 September, the agriculture ministries of Ukraine and Bulgaria agreed that they would exchange information on the export and import of certain agricultural products every seven days. Moreover, under the government’s deal with farmers, the National Customs Agency (NAM) is to closely monitor the volume of this category of Ukrainian goods passing through Bulgarian territory, and since 1 October farmers have received governmental compensation from a pool of €63 million, as proposed by Prime Minister Nikolai Denkov. No further arrangements between Sofia and Kyiv have been announced so far. A system of permits for the import of sunflower seeds, wheat, corn and rapeseed will start to operate in Bulgaria in December.

The imposition of a unilateral embargo was the subject of a broad political consensus in Slovakia, and was intended to serve the interests of local agricultural producers (40% of the country’s grain harvest is exported, mainly elsewhere in the EU). This means that Slovakia is unlikely to change its stance on this matter when the new cabinet is appointed, especially since Robert Fico, who was entrusted with forming a government after the parliamentary elections, was among the harshest critics of Ukraine’s WTO complaint. Fico raised this topic during the final stage of the campaign, and even claimed that the embargo would be extended to cover more agricultural products from Ukraine should Kyiv take retaliatory trade actions. On 21 September the agriculture ministers of both countries verbally agreed on the outline of a compromise solution; this envisages the reintroduction of grain trade based on a licensing system, in exchange for Ukraine refraining from filing a complaint. However, there are many indications that the deal will not stand because Kyiv has since brought the case to the WTO. Bratislava has not published any information about the agreement on government institutions’ websites, which most likely means that the initiative has fallen through.

Poland is still conducting negotiations with Ukraine. On 27 September, the agriculture ministers Robert Telus and Mykola Solskyi discussed the licensing system proposed by Ukraine, and Warsaw appealed to Kyiv to withdraw the WTO dispute. Ukraine did not agree to this, but its representative stated that “the disputes in the WTO are on hold for today”. The dispute itself has not yet formally started because the parties have 60 days for consultations from the moment of filing the case. Ukraine’s deputy economy minister Taras Kachka announced that negotiations with Warsaw could be resumed after the elections in Poland. He also emphasised that as of 6 October, no Ukrainian company had applied for a license to sell grain to Poland.

Hungary is not conducting any negotiations with Kyiv regarding lifting the ban. On 9 October, the government in Budapest decided to lift restrictions on importing sugar from Ukraine, but the embargo on a total of 24 products from this country is still in force.

Forecast

The surge in imports of grain from Ukraine has proved to be a real problem for the agricultural sectors of the Central European countries, due to the price competitiveness of Ukrainian grain which was exempt from customs duties. Since the spring of 2023, this issue has been raised by Central European farmers who organised mass protests, including blocking border crossings, if they found the response from their governments (or the EU) insufficient. Although grain does not have a major share in these countries’ imports, this issue will further strain political relations, unless their governments reach a lasting compromise with Kyiv.

Grain import from Ukraine is raising similar concerns in other countries too. In Croatia, which is a transit country for Ukrainian grain (through ports on the Danube and the Adriatic Sea), agricultural organisations have also began reporting the problem of uncontrolled inflows onto the local market and appealing to the government to introduce bans similar to those imposed by Poland, Hungary and Slovakia.

For Ukraine, it is crucial to maintain foreign sales of agricultural produce (especially grain) at the highest possible level because it is the country’s main export product. Kyiv has proposed introducing a producer licensing system, mainly because there is no alternative solution, given the determination to limit imports from Ukraine on the part of the five countries that have de facto ignored the European Commission’s lifting of the embargo.

At the same time, the increasing freight traffic along the new route from the Black Sea ports should ensure sufficient throughput for the export of agricultural products in the short run, unless the Russians damage a ship to make an example of it. In this situation, resuming their sales to neighbouring countries will no longer be a priority. However, the opening of the EU market has shown that relatively cheap grain from Ukraine, even when transported by land, competes successfully on the neighbouring markets. This means that in the future the Ukrainian government will make efforts to ensure that all the restrictions on its sale to its EU neighbours are lifted. This issue will undoubtedly be one of the most difficult problems to resolve as Ukraine’s accession negotiations are expected to start in the near future.

[1] A. Michalski, K. Nieczypor, I. Wiśniewska, ‘Grain under fire: agreement to unblock Black Sea ports’, OSW, 26 July 2022, osw.waw.pl.

[2] F. Rudnik, S. Matuszak, A. Michalski, ‘Russia’s game with the West: Moscow withdraws from the grain deal’, OSW, 18 July 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[3] Romania and Ukraine have been clearly deepening their political and economic cooperation over the past few months. For more information, see K. Całus, K. Nieczypor, ‘Zelensky in Bucharest: moving towards a new opening’, OSW, 11 October 2023, osw.waw.pl.