The state’s weakened immunity. The causes of the measles outbreak in Ukraine

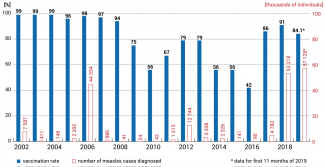

According to data compiled by the World Health Organization, since 2018 Ukraine has had the world’s second highest number of measles virus infections. A major increase in the number of individuals infected with measles has been recorded since 2017, when 4,782 cases of measles were diagnosed (in 2016 the corresponding number was a mere 90). In 2018, more than 54,000 infections were recorded, which accounted for more than 64% of all measles cases diagnosed across Europe. In 2019, the situation deteriorated even further. Ukraine’s Ministry of Health estimates that between January and November 2019 more than 57,000 individuals contracted measles. Altogether, in 2017–2019 in Ukraine more than 115,000 individuals caught measles and 41 of them died (including 25 children).

The main reason behind the rapid surge in the incidence rate is the low measles vaccination rate resulting from the crisis in the Ukrainian healthcare sector and from the spread of disinformation regarding the alleged adverse effects of vaccines and their ineffectiveness. This has caused the proportion of infants vaccinated against measles to fall to 42% in 2016, with the corresponding proportion recorded for children aged six and younger being 31%; these were among the world’s lowest vaccination rates. Measures taken by the Ministry of Health have resulted in a major increase in the vaccination rate in Ukrainian society and a reduction in the related epidemiological threat. A major problem continues to be posed by the illegal trade in fake vaccination certificates, which emerged as a result of a powerful anti-vaccination campaign on the Internet and of citizens’ distrust of state healthcare institutions. As a consequence, measles continues to be one of the biggest challenges faced by the state’s health policy.

Although the surge in the measles incidence rate in Ukraine is accompanied by an increase in the number of measles cases diagnosed across the world, the quick spread of the disease in Ukraine is linked with the emergence of circumstances which are favourable to it, even if they are not unique to Ukraine. Years of neglect in the healthcare sector and society’s susceptibility to disinformation can happen everywhere – in any country and any social group. All this makes the surge in the number of measles cases in Ukraine a topic for an interesting case study which needs to be analysed in detail.

Re-organisation in the time of crisis

The main reason behind the rapid surge in the number of measles cases is the poor state of the Ukrainian healthcare sector. This in turn results from the country’s difficult economic situation, as well as bad political decisions. In 2014, due to the political crisis ongoing at that time, the government failed to purchase a sufficient number of measles vaccines, which had a direct impact on the vaccination rate in Ukrainian society and contributed to an increase in the number of individuals contracting measles in subsequent years. The conflict in the Health Ministry’s executive body caused delays in supplying healthcare facilities with a sufficient number of vaccines.[1] It was triggered by accusations which Minister Oleh Musiy voiced against his deputy regarding the latter’s deliberate sabotage of public tender procedures involving the purchase of vaccines. The resignation of the minister and his deputy in autumn 2014 over the controversy over vaccine tenders resulted in the collapse of the vaccine procurement programme. Another important reason was the devaluation of the hryvnia. This led to the cost of purchasing vaccines considerably exceeding the funds earmarked for that purpose. As a consequence, the vaccines originally planned to be used in 2014 were purchased in 2015.

In 2014, in the wake of corruption scandals, a decision was made to dissolve the State Sanitary and Epidemiological Service and transfer its infectious disease monitoring, control and prevention powers to a newly-created institution. Due to the legal validity of the government’s decisions being questioned, the re-organisation process lasted until March 2017, triggering administrative chaos connected with an unclear division of powers between the dissolved service and the new bodies established in May 2016.[2] The difficult situation was further aggravated by the fact that between 2016 and 2019 the office of health minister remained vacant – over that period Ulana Suprun was the acting minister of health.

Disinformation and politics

The surge in the number of measles cases is also linked with increasing anti-vaccination propaganda, mainly spread on the Internet.[3] Information posted on social media questioning the point and the effectiveness of immunisation has convinced many parents to refuse to have their child vaccinated. Politicians have had a share in spreading fake news about vaccinations and have used cases of child deaths to promote themselves and to attack their opponents. In this context, the meetings and findings of a parliamentary committee established back in 2008 to investigate the death of a teenager in Kramatorsk deserve particular censure. This case received a lot of publicity nationwide and triggered a countrywide debate on the safety and efficacy of vaccines used in Ukraine.[4] Another report involved potentially lethal vaccines manufactured by a pharmaceutical plant in Kharkiv.[5] Although in both cases no connection between vaccination and death was established, they triggered waves of speculation regarding the adverse effects of vaccines and contributed to the spread of vaccine hesitancy in Ukrainian society.

The fight against anti-vaccination attitudes was hampered by the inconsistent interpretation of legal provisions. Despite the fact that pursuant to Ukrainian law all children are covered by a compulsory immunisation programme[6] and can only be enrolled in education institutions once they have had the required vaccinations, frequently this provision was not fully enforced. In 2016, a district court in Slavuta issued a decision in a leading case regarding a complaint lodged by a mother against the executive body of a kindergarten which had refused to enrol her child due to the absence of their vaccination certificate. As a result of this decision, unvaccinated children were allowed to be enrolled in schools. The court ruled that the kindergarten’s refusal was illegal and invoked the right to education as one of the fundamental human rights protected under the Ukrainian constitution (which means that it has precedence over the provisions of specific laws). In April 2019, Ukraine’s Supreme Court overruled the district court’s decision saying that the arguments presented by the complainant regarding the toxicity of vaccines were insufficiently substantiated and the requirement to have children immunised was legal due to important public interest.[7]

The fact that the number of measles cases is increasing in proportion to the declining vaccination rate recorded for Ukrainian society prompts the conclusion that vaccine hesitancy has directly translated into the rising measles incidence rate in recent years – in 2017 as many as 86% of measles cases were diagnosed in unvaccinated individuals.[8] The trade in fake vaccination certificates is another consequence of the spreading of misinformation about vaccinations. It is estimated that as many as 30% of medical certificates regarding vaccinations performed in Ukraine are fake. According to Ukrainian journalists, the price of such a certificate is around 350 hryvnias (around PLN 55).[9] Ukraine’s minister of Education and Science announced that managers of educational facilities will be held responsible for allowing unvaccinated children to attend classes. At present, the Ministry of Education is working alongside the Verkhovna Rada’s health committee on a legal framework to regulate the problem.[10]

The results of neglect

In 2014–2016, incorrect political decisions and increasing vaccine hesitancy resulted in a decline in the number of vaccinations performed in children, and in particular in infants. While in 2007 the infant vaccination rate was 97%, it fell to 56% in 2010, to 45% in 2014, and to 42% in 2016 (the corresponding vaccination rate recorded for children aged six and younger was 31%), which was among the world’s lowest rates. As a consequence, in 2017 the number of diagnosed measles cases increased 46-fold compared with 2016. It should be noted that the individuals who contracted measles were mainly children – in 2017 as many as 75% of all measles cases were diagnosed in children, in 2018 the proportion was 63%.[11] The highest measles incidence rate was recorded in Ukraine’s western oblasts, in particular in Lviv Oblast which neighbours Poland, and in Vinnytsia, Rivne and Khmelnitsky oblasts, and in Kyiv.

The measles outbreak in Ukraine has also triggered an increased incidence rate in other countries. In April 2019, in New York City’s Brooklyn borough, an increased measles incidence rate was recorded in Orthodox Jewish communities, which resulted in a public health emergency being declared. The virus made its way to the United States from Israel, where it was diagnosed in individuals who had visited places of religious worship in Ukraine (each year thousands of Hasidic Jews go on a pilgrimage to tzadiks’ graves).[12]

In 2019, the increased measles incidence rate in Europe was mainly recorded in the former Soviet republics. Aside from Ukraine, which has topped this negative ranking for two years now, the highest number of measles cases was recorded in Georgia (4,389) and the Russian Federation (4,054), followed by Turkey (2,811), France (2,657), Northern Macedonia (1,897) and Romania (1,746).[13] In each of these countries, the spread of the measles virus is linked with a decline in the population’s vaccination rate due to individuals refusing or ignoring the need to have themselves or their children vaccinated. A data analysis shows that although in a significant number of European countries most residents have been vaccinated, the high mobility of Europeans facilitates the emergence of local isolated areas of increased measles incidence and the spread of the disease to other locations.

The response from the authorities

The first measure undertaken by the Ukrainian authorities to respond to delays in supplying the sufficient number of vaccines in 2014 involved a modification to the system of procuring medicinal products, including batches of vaccines. Pursuant to a law enacted in March 2015, purchases of medicinal products were to be effected via international organisations such as UNICEF and the UNDP, as well as the British company Crown Agents, until the end of March 2020. According to data compiled by the Ministry of Health, the introduction of new regulations facilitated a 40% reduction in the costs of purchase of medicinal products and helped procure the sufficient number of vaccines for all age groups in 2018. In January 2019, the government introduced a three-year planning scheme regarding the purchase of vaccines, which envisages the procurement of an additional 25% of vaccine doses to be used in case of emergency.

Despite the alarming statistics regarding the surge in the number of measles cases, the Ministry of Health decided against declaring an epidemic. Instead, it chose to take provisional measures (temporarily shutting down schools, carrying out vaccination campaigns, launching mobile vaccination clinics). In May 2019, the ministry announced free access to vaccinations for all citizens regardless of their age and profession (formerly free vaccination programmes were offered to healthcare professionals, school employees, soldiers and students, and citizens aged 30 and younger). Alongside this, the age threshold for children entitled to receive the first dose of the measles vaccine was lowered to six months (formerly vaccinations were performed in children aged one and older). In addition, an awareness-raising campaign on vaccinations was organised with the participation of Prime Minister Oleksiy Honcharuk and Metropolitan Epiphanius, the head of the autocephalous Orthodox Church of Ukraine.

These measures have resulted in a major improvement in Ukrainian society’s vaccination rate. In 2017, the infant vaccination rate was 88%, in 2018 it was 91%, and at the end of November 2019 the vaccination rate recorded for children aged one and younger was almost 85%.[14] According to the Public Health Centre’s acting director general, as a result of efforts made by the Ukrainian healthcare sector and international humanitarian organisations, the measles epidemic has been on the wane.[15] The experience gained so far during the rapid spread of the disease was, at the end of November 2019, crowned by the Ukrainian government adopting the Strategy for the development of immunological prevention and protection of the population against infectious diseases until 2022. This obliges the authorities for example to guarantee sufficient funding for activities intended to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, to implement a programme providing residents with access to reliable and scientifically proven information on the importance of immunisation and to devise a response plan to be used in situations of sudden increases in the number of individuals contracting infectious diseases.

The crisis of the state’s credibility

Despite successful measures carried out by the government in Kyiv to boost society’s vaccination rate, many Ukrainians continue to be sceptical about this type of disease prevention. Public opinion polls show that in Ukraine the effectiveness of anti-vaccine propaganda is closely linked with citizens’ distrust of state institutions. More than a third of the respondents argue that the activities carried out by the Ministry of Health have no impact on their health and more than half of them have doubts about the competence of the employees of public healthcare facilities.[16] As many as 29% of Ukrainians view immunisation as harmful to health and a mere half consider it effective.[17] A mere 66% of the respondents believe that immunisation programmes should be compulsory for children, and 27% oppose this view. In this context, it should be noted that, regardless of their opinion on whether immunisation should be compulsory, the vast majority of citizens (73%) believe that it should mainly be left for the parents, and not for the state, to decide whether a child should be vaccinated.[18]

The above-mentioned statistics show the immense challenge faced by the authorities as regards the state’s awareness-raising policy in the field of disease prevention. Ukrainian society continues to be susceptible to fake news and manipulated information on the safety of immunisation. This boosts the risk of evading compulsory immunisation programmes in a situation of increased anti-vaccine propaganda which uses widely publicised cases of individuals contracting a disease or dying (which are mistakenly attributed to vaccination procedures carried out at that time). In this situation, the only way to eliminate the effects of fake news is through activities carried out by state institutions capable of successfully counteracting the spread of beliefs which are harmful to public health. This is all the more important in the context of increasing media hype and the blurring of responsibility for publishing fake news on the Internet and on social media sites. Due to Ukraine’s ongoing crisis of the state’s credibility, its society continues to be susceptible to conspiracy theories regarding the safety and efficacy of vaccines. This makes these theories the most serious obstacle to preventing the return of disease outbreaks in the future.

Appendix. Vaccination rate and number of measles cases diagnosed in Ukraine in 2002–2019

Source: World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/burden/vpd/surveillance_type/active/measles_monthlydata/en/.

[1] М. Бродский, ‘Тендеры смерти’, Зеркало недели, 3 October 2014, www.zn.ua.

[2] See Є. Прохоренко, ‘Що буде після ліквідації СЕС?’, Еженедельник АПТЕКА, 3 October 2016, www.apteka.ua. At present, the monitoring of epidemiological threats is the task of the Public Health Centre, established in May 2016 at the Ministry of Health. The State Epidemiological and Sanitary Service was dissolved in March 2017.

[3] An analysis of posts on social media sites carried out by researchers from the George Washington University has revealed that the global increase in the number of measles cases in 2014–2017 correlates with the increased activity of fake Internet accounts established in Russia. The content spread by Russian Internet bots involved similar threads posted on various sites, including doubts about the adverse effects of vaccines, vaccine quality and parents’ rights to decide whether to have their child vaccinated or not. See D.A. Broniatowski et al., ‘Weaponized Health Communication: Twitter Bots and Russian Trolls Amplify the Vaccine Debate’, American Journal of Public Health, October 2018, no. 108(10), pp. 1378–1384, ajph.aphapublications.org.

[4] The death of a 17-year-old boy the day after receiving a measles vaccine is viewed as the beginning of the anti-vaccination campaign in Ukraine. The findings of a parliamentary investigative committee and the government’s decision to suspend the immunisation programme in schools until the committee publishes its final report (the ban was in place for several months) gave rise to conspiracy theories. In their report from the committee’s work, the parliamentarians argued that the boy’s death resulted from the low quality of vaccines imported from India. The results of the committee’s work were challenged by a specially appointed group of WHO experts, who discovered that the cause of the teenager’s death was septic shock triggered by an infection, rather than administration of the vaccine. See ‘ВООЗ: Смерть підлітка в Краматорську не пов’язана зі щепленням’, Радіо Свобода, 5 November 2008, www.radiosvoboda.org. Although the Ministry of Health rejected the findings of the parliamentary committee, in 2010, under pressure from the public, the ministry decided to destroy around 8 million doses of the Indian-made vaccine. By doing so, it lost its entire stock of this product. Х. Коновалова, ‘Смертельную вакцину уничтожат’, Сегодня, 15 April 2010, www.segodnya.ua.

[5] The death of 11 children in 2012 resulting from the administration of vaccines whose quality had allegedly not been checked gave rise to attacks against the then Minister of Health Raisa Bohatyrova from opposition politicians. At the time Ms Bohatyrova’s son co-owned the plant which manufactured the vaccines. ‘У МОЗ кажуть, що вакцини сина Богатирьової безпечні і від них ніхто не помирав’, Українська правда, 24 January 2013, www.pravda.com.ua.

[6] In line with disease prevention requirements, the compulsory measles vaccination programme covers children aged one and older (first dose of vaccine) and children aged six and older (second dose). ‘В Україні оновлено Національний календар профілактичних щеплень’, Міністерство охорони здоров’я України, 5 July 2018, www.moz.gov.ua.

[7] ‘Верховний Суд прийняв рішення на користь обов'язкової вакцинації’, Левый берег, 29 May 2019, ukr.lb.ua.

[8] ‘У 2017 році в Україні на кір захворіли понад 4 700 осіб – МОЗ’, Униан, 16 January 2018, www.unian.ua.

[9] ‘В ЮНІСЕФ оцінюють у близько 30% кількість фальшивих довідок про вакцинацію’, Радіо Свобода, 14 May 2018, www.radiosvoboda.org.

[10] ‘Новосад: За чотири місяці ми виконали 70% з того, що пообіцяли’, Інтерфакс-Україна, 20 January 2020, ua.interfax.com.ua.

[11] ‘У 2018 році на кір захворіли понад 54 тисячі українців. Зупинити поширення хвороби може лише вакцинація’, Міністерство охорони здоров’я України, 2 January 2019, www.moz.gov.ua.

[12] D.G. McNeil Jr., ‘Scientists Thought They Had Measles Cornered. They Were Wrong’, The New York Times, 3 April 2019, www.nytimes.com.

[13] Measles and rubella monthly update for the WHO European Region, World Health Organization, 8 January 2020, www.euro.who.int.

[14] ‘Відповіді на поширені питання про вакцинацію від кору’, Міністерство охорони здоров’я України, 7 March 2019, www.moz.gov.ua.

[15] ‘Реліз Круглого столу “Стратегія розвитку імунопрофілактики та захисту населення від інфекційних хвороб”’, Батьки за вакцинацію, 23 December 2019, www.bzv.org.ua.

[16] ‘Оценка медицинской сферы в Украине: июнь 2018’, Рейтинг, 9 July 2018, www.ratinggroup.ua.

[17] For comparison, in Poland 78% of the respondents consider immunisation safe and 84% view it as effective. See Wellcome Global Monitor 2018, Wellcome Trust, 19 July 2019, wellcome.ac.uk.

[18] ‘Оценка медицинской сферы в Украине…’, op. cit. For comparison, in Poland 87% of the respondents are in favour of compulsory immunisation and a mere 9% support the view that it should be voluntary. See ‘Stosunek do szczepień ochronnych dzieci’, Komunikat z Badań, January 2019, no. 9/2019, CBOS, www.cbos.pl.