Turkey and the US: a costly normalisation

On 25 September, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, met with his American counterpart Donald Trump at the White House. During the visit, a memorandum on strategic co-operation in the field of civil nuclear energy was signed – most likely including the use of small modular reactors (SMRs) – and an agreement was reached on the purchase by Turkish Airlines of 225 Boeings worth approximately $22 billion. A contract was also concluded for Turkey to purchase $43 billion worth of American LNG over 20 years. The parties also emphasised their support for the unity and territorial integrity of Syria. In addition, they discussed contentious issues – above all, the sale of F-35 fighter jets to Turkey, the US sanctions imposed on it for purchasing the S-400 system from Russia, as well as the modernisation of the existing F-16 fighter jets and the acquisition of new ones. No breakthrough was achieved on these matters, although the leaders of both states stressed that the talks were moving in the right direction. However, their declarations were overshadowed by Trump’s remark that resolving the problems would require concessions on the part of Turkey, and by his call for Turkey to cease importing Russian oil.

From the Turkish perspective, the meeting was intended to mark the culmination of the normalisation process with the US, initiated after Trump assumed office. The signing of high-value contracts was meant to persuade him to make greater concessions. The results of Erdoğan’s visit suggest that it should be regarded as an important step towards improving bilateral relations. However, full normalisation remains far from easy, and its pace will most likely depend on Turkey’s willingness to meet Trump’s demands.

A large catalogue of disputes

Turkish–American relations in the past decade have been exceptionally tense (see ‘A catalogue of disputes. The head of Turkish diplomacy visits the US’). The greatest controversies between the two states were stirred by policy on Syria, especially after 2015 – a consequence of the United States establishing co-operation with the Syrian Kurds, first in the form of the People’s Defence Units (YPG), and later the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), built mainly from YPG’s ranks. Washington decided to co-operate with YPG, among other reasons, following the failure of the Turkish–American programme to train the Syrian opposition to fight against so-called Islamic State (IS). The Kurds proved to be a more effective force, and determined to combat the jihadists. Turkey, however, regarded YPG as the Syrian extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – an organisation considered terrorist not only by Ankara itself but also by Washington. It therefore argued that its American ally was cooperating with terrorists, thereby undermining its security interests. Turkey was also concerned about the territorial aspirations of the Syrian Kurds – decision-makers feared that this community’s drive to build autonomy in Syria would spill over into the south-eastern part of Turkey.

Another serious problem was Turkey’s purchase of the Russian S-400 air and missile defence system in 2017. Washington had long signalled to Ankara that it should not conclude the transaction, as the deployment of the system in Turkey would have negative consequences for the integrated NATO air defence system, which Turkey is a part of. The United States feared that the data collected by the S-400 radars would be readily accessible to Moscow and would reveal the stealth characteristics of F-35 aircraft. The Turkish side regarded these arguments as political and claimed it had been forced to acquire the S-400 from Russia because its allies were unwilling to sell it the Patriot system on terms it found acceptable (it was particularly interested in a transfer of technology). When Turkey refused to abandon the deal with Russia, the first Trump administration took unprecedented steps. First, in July 2019, it excluded Turkey from the consortium producing the F-35 fighter jet and denied it the purchase of the aircraft. Then, in December 2020, it imposed sanctions which, among other measures, included a ban on export licences for US technologies and goods to Turkey’s Presidency of Defence Industries, thereby hampering Turkey’s access to US-made military components.

Turkish–American relations were also affected by the refusal to extradite Fethullah Gülen, the Muslim cleric residing in the United States whom Turkey accused of orchestrating the failed coup attempt in 2016. This reinforced conspiracy theories popular in Turkey that Western allies had been behind the coup attempt, and contributed to the country’s anti-Western turn in foreign policy. Another issue was the case of Turkey’s Halkbank, which had allegedly been involved in circumventing sanctions against Iran.

Seeking normalisation

After the second Trump administration took office in Washington, Turkey began efforts to rebuild its relations with the United States, as it saw the new president as more open to seeking solutions than Joe Biden, who had not attached much importance to relations with it and had described Erdoğan as a dictator in pre-election interviews.

Syria became an important element of Turkey’s approach to the United States. At the end of 2024 the country saw a regime change, as a result of which power was taken over by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, a group allied with Ankara. Turkey presented itself to the US as a key regional player, ready to participate in the stabilisation of the Syrian state and seeking its unification within its current borders (see ‘Turkey’s Syrian dilemmas: success and the road ahead’). Turkey’s emphasis on its readiness to support both the government in Damascus and the United States in the fight against terrorist groups was another step in the process of improving bilateral relations. This referred not only to the Kurdish organisations it regarded as terrorist, but also to the remnants of IS. By demonstrating its determination to combat jihadists, Ankara sought to persuade Washington to abandon its co-operation with YPG. It was also intended as a signal directed specifically at Trump – Turkey wished to present itself as an actor capable of assisting in the pursuit of American interests in the region and enabling the United States to bring its military operation in Syria to an end (approximately 2,000 US soldiers are currently stationed there).

Tom Barrack – the United States ambassador to Turkey since May 2025 and special envoy for Syria – also played an important role in the process of improving bilateral relations. He emphasised Turkey’s strategic significance as an important NATO ally and a potential US partner in stabilising the Middle East. He also supported negotiations concerning the defence sector, arguing that Turkey’s re-entry into the F-35 programme would strengthen ties between the two states and bolster Washington’s position in the region. In addition, in May 2025 he co-founded the US–Turkey Syria Working Group, intended to improve the coordination of actions in the fields of security and stability in that country. Barrack made a good impression on Turkish decision-makers by supporting their vision of integrating Kurdish forces into the Syrian government army. On several occasions he also underlined Turkey’s central role in the fight against IS.

The improvement of bilateral relations was also influenced by Turkey’s stance on the war in Ukraine. It emphasised its support for Trump’s efforts to resolve the conflict (see ‘Turkey in Trump’s world: when in trouble turn to Europe?’). It sought to present itself as a mediator in negotiations between Moscow and Kyiv, as well as an intermediary in dialogue between the United States and Russia (in February and April 2025, representatives of both states met in Istanbul). To strengthen its image in Washington as a constructive regional actor, in the initial weeks of the US president’s term Turkey adopted a cautious approach towards Israel’s actions in the Gaza Strip and the Middle East.

The path to rebuilding the alliance is not easy

The Turkish side prepared well for Erdoğan’s talks with Trump and achieved successes in the form of the Americans' confirmation of a shared vision for Syria and assurances of a willingness to continue normalizing bilateral relations. Moreover, Trump suggested that this could happen quickly. However, it remains problematic for Turkey that no breakthrough was achieved on the most important issues, particularly its return to the F-35 programme or the lifting of US sanctions. Turkey was certainly aware that resolving these problems would not be easy. However, they may have been surprised by Trump's assertiveness—pointing to his readiness to make concessions on these matters in exchange for unspecified steps that Ankara must take first, as well as his call to cease importing Russian oil.

Trump’s attitude suggests that further negotiations between Turkey and the United States may prove complicated. In these talks, Washington may argue that on two sensitive issues – the sale of F-35 fighter jets and the lifting of sanctions – it intends to apply a strict interpretation of Section 1245 of the National Defence Authorisation Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (NDAA FY2020) and Section 1241 of the National Defence Authorisation Act for Fiscal Year 2021 (NDAA FY2021). These make any breakthrough in these areas conditional on confirmation by the Secretaries of Defence and State (NDAA FY2020 concerning the F-35) and by the President (NDAA FY2021 concerning CAATSA) to the relevant bodies that Turkey: a) has removed all its S-400 equipment and personnel, b) has ensured that the S-400 or any equipment acquired to replace it is neither operated nor maintained in the country by Russia, c) will provide guarantees that it will never purchase the S-400 or its successors.

Meeting these requirements has been the subject of intensive negotiations over the past five years. During this period, the US approach has shifted – above all by narrowing the definition of ‘Turkey’s possession of the S-400’, to which Ankara was unwilling to agree in any case. A hardening of Washington’s stance and the linking of its conditions to Turkey’s purchases of Russian oil could further weaken Ankara’s negotiating position.

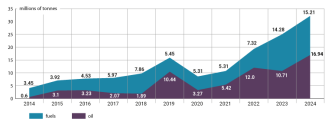

Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, Ankara has tripled its imports of crude oil and petroleum-derived fuels from Russia (see Chart), partly for refining and re-exporting them to foreign markets, including the EU. This has enabled it to save billions of dollars on energy bills thanks to discounted prices for the imported raw material (as much as $5–20 less per barrel when purchasing Urals crude), while generating profits from the sale of refined products. Moving away from this arrangement could mean higher fuel and energy costs for Turkey.

Turkey may propose a symbolic reduction in imports of Russian oil, but it is most likely to oppose a complete halt to its purchase. The agreement with the United States on LNG, as well as the resumption of oil supplies from Iraqi Kurdistan to Turkey thanks to US mediation – which coincided with Erdoğan’s visit to Washington – will change little in this respect, as they will not cause any immediate improvement in the country’s energy situation.

Chart. Turkey’s oil and fuel imports from Russia

Source: Turkey’s Energy Market Regulatory Authority, epdk.gov.tr.