Ukraine: new government led by Yuliia Svyrydenko

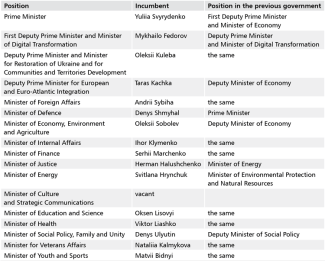

On 17 July, the Verkhovna Rada voted (with 262 in favour and 22 against) to appoint Yuliia Svyrydenko as Prime Minister and approved the composition of her government. Mykhailo Fedorov, the former Minister for Digital Transformation, became the First Deputy Prime Minister. The dismissed Prime Minister, Denys Shmyhal, was appointed Minister of Defence, with that ministry merged with the Ministry of Strategic Industries. The ministries of Economy, Environment and Agricultural Policy were consolidated into a single entity, now headed by Oleksii Sobolev, formerly Svyrydenko’s deputy at the Ministry of Economy. Oversight of the Ministry of Justice was again separated from the post of Deputy Prime Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration. Olha Stefanishyna, who until recently was responsible for this area, was appointed presidential envoy for the development of cooperation with the United States. The Ministry of Justice was taken over by Herman Halushchenko, previously Minister of Energy. Taras Kachka, who until now served as Deputy Minister of Economy, will be responsible for integration with the European Union and NATO. Andrii Sybiha retained his position as Minister of Foreign Affairs.

The government reshuffle is not expected to bring significant changes to Ukraine’s domestic or foreign policy. The shake-up was primarily driven by corruption scandals involving some ministers, rather than a declared intention to introduce new faces. In Ukraine, the government is not the main body setting the reform agenda or making key decisions. This role belongs to the office of the president, while the Cabinet of Ministers carries out its directives.

Commentary

- The appointment of Svyrydenko has strengthened Andrii Yermak’s influence over the government. The new prime minister is closely associated with the head of the Office of the President, who is effectively the second most influential politician in the country after the president. She is also known for showing limited assertiveness in her dealings with Yermak. Unlike her predecessor, she lacks significant experience in balancing the interests of various factions within the ruling camp with the instructions coming from the president’s inner circle.

- Most likely, the changes have been triggered by corruption scandals. In June this year, the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) was preparing to bring charges against Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for National Unity, Oleksii Chernyshov. To avoid this, he extended his foreign visits by several days. It was only after talks with Timur Mindich, a trusted associate of Volodymyr Zelensky and co-owner of the Kvartal 95 studio founded by the current president, that Chernyshov returned to Ukraine, where he was formally charged. Meanwhile, Deputy Prime Minister Stefanishyna has faced corruption allegations since 2019, and in recent months journalists have uncovered several new scandals involving her. The government reshuffle therefore allows the authorities to replace problematic ministers and address reputational issues without openly admitting that the dismissals are linked to corruption. Chernyshov, notably, has close links with the Zelensky family. However, despite corruption scandals within the Ministry of Energy, Herman Halushchenko remains in the cabinet, now serving as Minister of Justice – most likely thanks to Mindich’s protection.

- The changes may have also been triggered by public demand for new faces in politics. Since Donald Trump’s return to the US presidency, Ukrainian politicians have been anticipating a ceasefire that would, among other things, allow new elections to be scheduled. However, with elections still legally impossible due to the ongoing war and widespread dissatisfaction with the Cabinet of Ministers – according to a March survey by the Razumkov Centre, over 70% of respondents did not trust the government and 67% did not trust Prime Minister Shmyhal – the authorities opted for a staff reshuffle to give the appearance of responding to public sentiment and political developments. In practice, most changes (with the exception of the Ministry of Culture) consisted of promoting deputy ministers to ministerial posts and swapping the heads of certain ministries (see Appendix 1). The opposition described these moves as ‘rearranging deckchairs.’

- The nomination of Taras Kachka as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for European Integration may lead to a more assertive tone from Kyiv towards the EU. It is an attempt to create the impression of a fresh start in fulfilling commitments to the Union, especially given the European Commission’s criticism of stalled judicial reforms. At the same time, this move signals a potentially more confrontational approach by Kyiv in future negotiations with the EU, particularly in view of opposition from some member states – including all of Ukraine’s EU neighbours – to provisions of the new trade agreement. Kachka is known for his undiplomatic language and firm negotiating stance. In 2023, he threatened Poland with an embargo on apple and vegetable imports in response to the ban on Ukrainian agricultural products. In March this year, he also suggested retaliatory measures against countries that, in his view, were obstructing negotiations on the terms of the trade deal with the EU. Kachka was also among the negotiators of the raw materials agreement with the United States.

- The merger of several ministries under the leadership of Sobolev is intended to streamline economic policy-making. However, past experience with the creation of similar ‘super-ministries’ in Ukraine suggests that they rarely fulfil this purpose. Beyond Sobolev, the government lacks figures closely aligned with Svyrydenko, which means that in the event of conflicts she will have to rely on support from the Office of the President. Yermak’s influence may be counterbalanced to some extent by the promotion of Mykhailo Fedorov, who is strongly connected to Zelensky, to the role of First Deputy Prime Minister, as well as by Shmyhal’s continued presence in government.

- As part of the reshuffle, the government reorganised the unconventional ministries created in 2024, which had failed to fulfil their intended roles. The changes affected the Ministry of Culture and Strategic Communications. Initially, this body was meant to combat Russian propaganda, but that concept has now been abandoned. The institution has been transformed into the Ministry of Culture, although its leadership position will remain vacant for the time being. The Ministry of National Unity, originally tasked with encouraging the return of Ukrainians from abroad, has been merged with the Ministry of Social Policy.

Appendix 1. Prime Minister Svyrydenko’s biography

Yuliia Svyrydenko (born 1985 in Chernihiv) is a civil servant and economist. In 2008, she graduated from the Kyiv National University of Trade and Economics. Between 2008 and 2011, she worked at the agricultural company AMP. From 2011, she headed the permanent representation of Chernihiv in its partner city Wuxi in China. In May 2015, she became an adviser to Valerii Kulich, head of the Chernihiv Regional State Administration, and was appointed his deputy two years later. From July to November 2018, she served as acting head of the administration. In September 2019, she was appointed Deputy Minister of Economy, where she was involved, among other tasks, in labour law reform. In December 2020, she became deputy to Andrii Yermak, head of the Office of the President of Ukraine, with responsibility for economic policy. From November 2021, she served as First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Economy in Denys Shmyhal’s government. In 2025, she led negotiations with the United States on the terms of the raw materials agreement.

She is regarded as a non-confrontational figure and has not been implicated in any major scandals. In April this year, the opposition accused her of a conflict of interest related to earnings from lectures at the private Kyiv School of Economics. Over the course of a year, she received more than 3 million hryvnias (over € 61,370) for this work, while an NGO affiliated with the school was among the beneficiaries of a foreign grant awarded by the Ministry of Economy. No formal charges were brought against her.

Appendix 2. The Svyrydenko cabinet