Piotr Żochowski

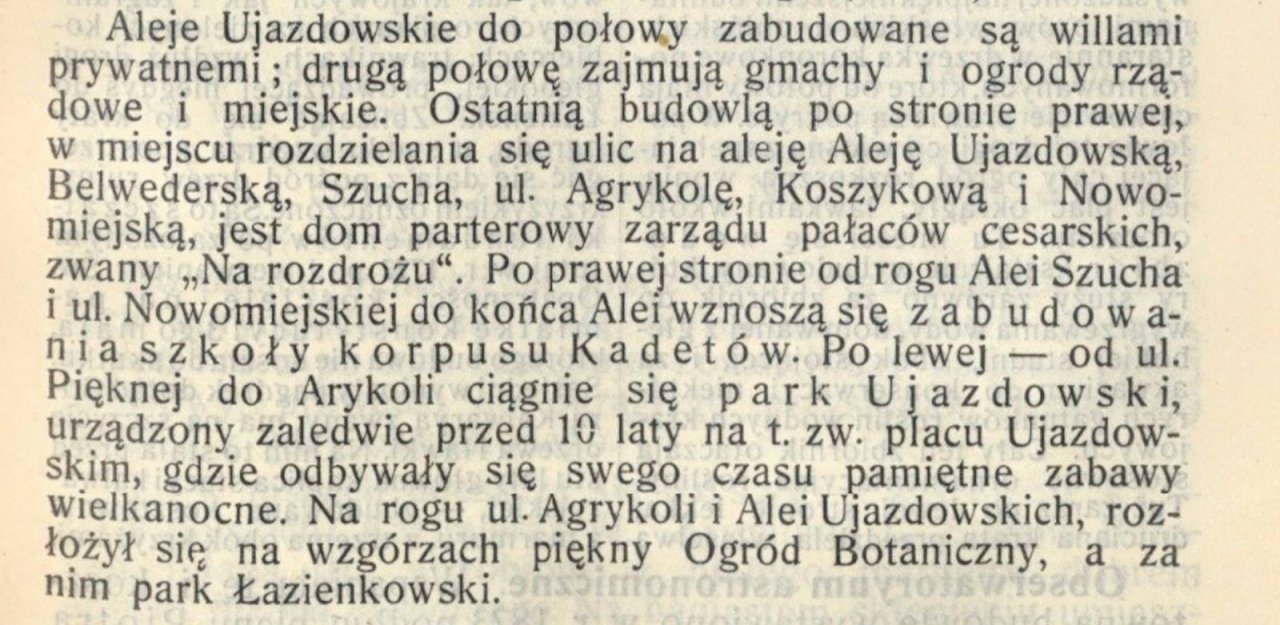

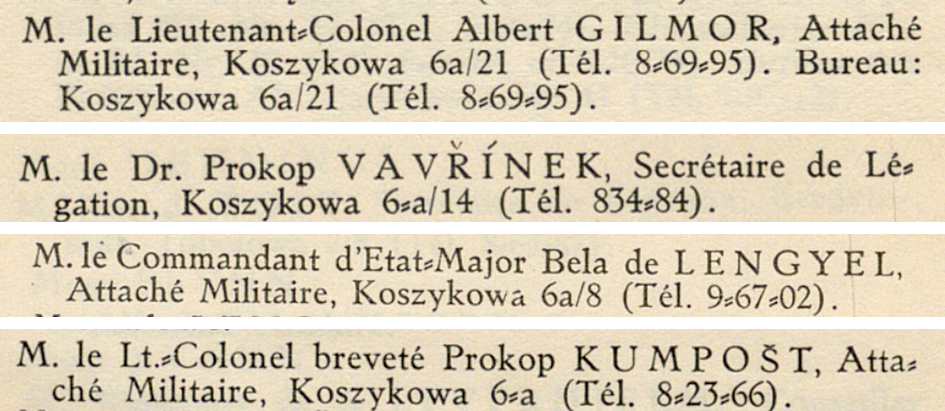

Warsaw, 6a Koszykowa street. One of many addresses in Warsaw. Those who have come across the Centre for Eastern Studies associate this address with its headquarters. It is easy to find if you know where Plac Na Rozdrożu square is. Its location is unique, as it is adjacent to objects of key importance for the city’s history: the Royal Route, the architectural project known as the King Stanisław Axis (Oś Stanisławowska), Łazienki Park, Ujazdów Park and the Łazienkowska expressway (which spans the Vistula River), the Prime Minister’s Office, the Ministry of National Defence, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Education, the Central Anti-Corruption Bureau. Also: the papal Nunciature and the embassies of Russia, Ukraine, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Finland, Germany and France.

The Centre for Eastern Studies occupies the ground floor and top three floors of a tenement house. Inside, traces of the building’s originally intended use can still be seen – a house with 3-4 flats on each floor, a staircase in art déco style and – this being the most characteristic feature – a corner finial reminiscent of a turret, a twin reflection of which draws attention to the neighbouring tenement house located at 6 Koszykowa street. Subsequent post-war adaptations of the house to turn it into an office building have not managed to quash the spirit of a pre-war tenement house. However, knowledge about its historical context – not just in relation to the city but also the country as a whole – has vanished from public consciousness. When you are at 6a Koszykowa it is worth looking back, exploring its immediate surroundings and grasping the unique nature of this place. The area around Centre for Eastern Studies and its past is bounded by by Aleje Ujazdowskie, Plac Na Rozdrożu, Aleja Szucha, Mokotowska, Służewska and Natolińska streets, Aleja Róż and Aleja Przyjaciół and a street familiar to just a few: św. Teresy street.

When Koszyki became Koszykowa

Those who make puns and riddles about OSW, when asked about the origin of the street’s name, respond by pretending that it is actually linked to the forgotten Russian intellectualist, Fedor Koshikov. However, regardless of most sincere intentions to find a link between its name and a patron who is directly associated with the eastern direction of research and analysis, no source has been found to support this interpretation.

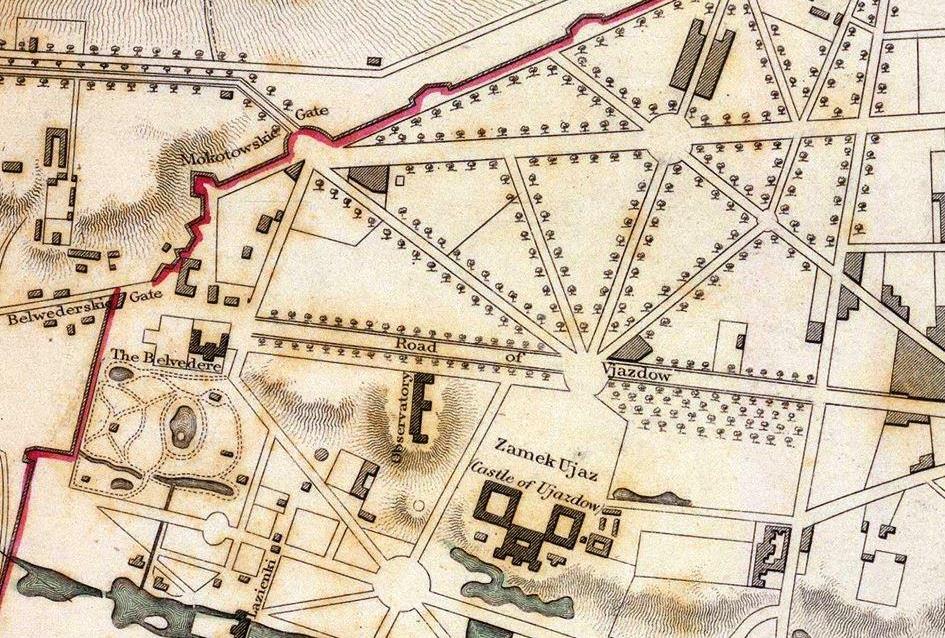

The spoken tradition of Warsaw links its name to Hala Koszyki, a shopping centre built at the beginning of the 20th century and existing until the present day, “because goods were offered in baskets there” (the Polish word koszyki means small baskets). Appealing as this interpretation may seem, it is still untrue. The name of the street originates from Koszyki Grange, which was established in the early 18th century, and its fields and orchards extended to what today is Plac Politechniki in the direction of Plac Na Rozdrożu. Its name reportedly originated from one of the occupations of its residents: weaving wicker baskets. Another version takes into account the use of wicker baskets for delimiting the then boundaries of Warsaw, the so-called Lubomirski Trenches or Embankments (Polish Okopy or Wały Lubomirskiego – the red line on the map fragment).

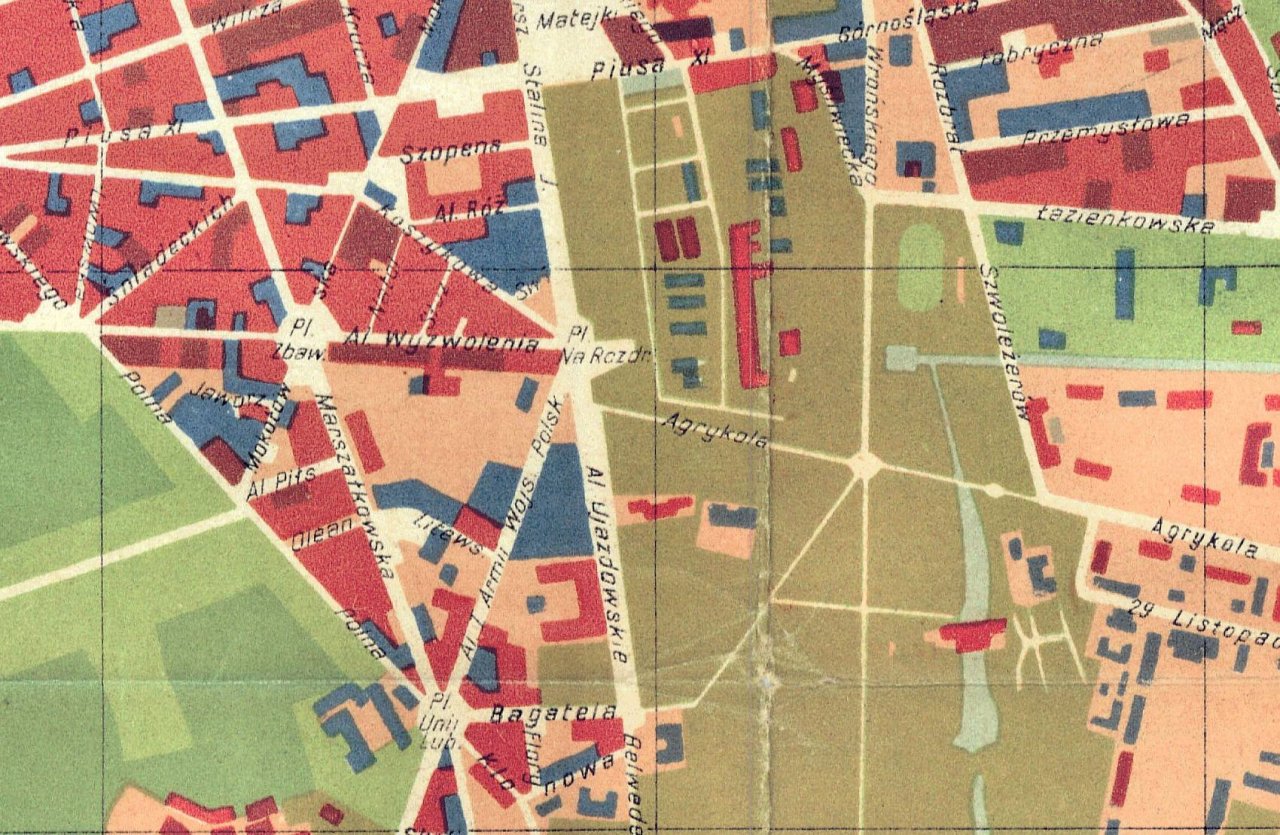

They were created in 1770 to strengthen sanitary control at the time of the plague epidemics that was sweeping across the country, although this was merely an excuse, while the real intention was to control traffic to the city and collect entry fees. The line of the trenches (embankments) started in Czerniaków, surrounded Łazienki Park and the Belvedere to run further along what now are Polna and Koszykowa streets, which set the boundaries of Warsaw until 1916. Mokotów Turnpikes at Plac Unii Lubelskiej are the remnants of the embankment line. The Koszyki road until 1825 was the frontier street, and the embankment that set the frontier was built of baskets filled with earth, which allegedly provided grounds for naming the street later. This version would have been likely, if not for the fact that the Koszyki Grange was established in early 18th century before King Stanisław Axis was designed and the existing field roads – ‘to Nowa Wieś i.e. New Village’ (Nowowiejska) and ‘to Koszyki’ – were adapted to fit this city planning project. The Lubomirski Trenches were levelled with the ground in 1875, and the fields and orchards would gradually be replaced with urban development. The present name of the street has been in use since around 1885. The tradition clearly links Koszykowa with the wicker baskets that were made in the area which later became part of the Koszyki Grange.

Without giving up the search for possible links between the name of the street and OSW’s mission, it is worth paying attention to etymology of the Polish word kosz. Zygmunt Gloger, the author of Encyklopedia Staropolska (Old Polish Encyclopaedia) derived this name from the Turkish word koç meaning “a Tatar camp, its Polonised version being koczowisko. Poles used to call kosz or tabor a camp in the field surrounded with carts to protect it from a sudden enemy attack. (…) The word kosz was also used to refer to the Zaporizhian Sich (hence the term kosz ataman) and individual Ukrainian castles, the guardhouses used by Polish knights and Cossacks to protect the peasants from Tatar attacks. These koszs or castles were usually located next to large routes; to name just a few: Bila Tserkva, Uman, Savran, Bar, Nemyriv, Trakhtemyriv, Cherkasy and Kodak”. Thus etymology takes the side of OSW, which is located at Koszykowa street for a reason.

On King Stanisław Axis – Plac Na Rozdrożu

It is not difficult to find the headquarters of OSW. All you need do is ask for directions to Plac Na Rozdrożu, a square whose location is familiar to most Varsovians. One of the streets radiating from it is Koszykowa, and the unique tenement house number, 6a, can be seen from the square when you look in the north-western direction. What is the secret of this easy-to-spot location? It could be explained by the history of the city’s spatial development. The architectural axis was planned in 1768–1773, when King Stanisław August Poniatowski, who took French solutions as a model, accepted the spatial planning design based on a network of squares with streets running from them in a star-like manner. The Axis stretched from the east to the west along what is now Nowowiejska street and was expected to provide a link between the king’s mansion in Ujazdów Castle on the outskirts of Warsaw and the western suburbs of the city. It is believed that the authors of the design are Ephraim Schröger, an architect of German origin, and August Fryderyk Moszyński, a Freemason and a patron of art, the author of the concept of redevelopment of Uzadów Castle and its surroundings. It is thanks to him that the squares Plac Na Rozdrożu, Plac Unii Lubelskiej and Plac Zbawiciela were delineated in 1768. This layout, which was intended to resemble the layout of the streets in the capital city of France, allowed devotees of this region of Warsaw to call it ‘little Paris’. It was only towards the end of the 19th century that buildings were erected along the delineated squares and streets, and the city planning design was used in the 1950s on the occasion of the construction of Marszałkowska Residential District, which was built in the socialist realism style. Its characteristic element is the housing development Latawiec at Aleja Wyzwolenia, close to Koszykowa and OSW. The centuries-old perspective of Plac Na Rozdrożu was disrupted due to the liquidation of one of the avenues along which excavations were made in 1972–1974, with the construction of the Łazienkowska expressway in mind.

Plac Na Rozdrożu – the one that does not exist

Plac Na Rozdrożu started to serve as a meeting place in the 19th century. Along with Plac Ujazdowski, which was located in the territory of the present park, it was used for public parties, exhibitions and military exercises. Under Russian occupation this region was also of military significance. The barracks of the Lithuanian Lifeguard Regiment were located nearby, and the Main Military Hospital, commonly known as Ujazdów Hospital, was established in 1818 by order of Grand Duke Konstantin Romanov. The hospital complex consisted of twenty red-brick pavilions that were built towards the end of the 19th century. After Poland regained independence, the complex provided venue to a military school of sanitary services. As a consequence of the constant presence of the Russian military unit (“regiment”), the Church of the Archangel Michael (an Orthodox wooden church) was built in 1894 at Plac Na Rozdrożu. It was situated on the eastern side of the square, where the Łazienkowska expressway runs presently. The church was demolished in 1923.

The changes in the area around Koszykowa street gained momentum towards the end of the 19th century. One of the major projects, which added prestige to its surroundings, was the creation of Ujazdów Park in 1893-1896. Over time, the park and Aleje Ujazdowskie have become a favourite place for Varsovians to take a stroll on Sunday.

In the inter-war period, Plac Na Rozdrożu also became a place for patriotic demonstrations and military parades. Another thing that added prestige to the square was the fact that state institutions were situated close to it: the Ministry of Military Affairs on the former 6 Sierpnia street (present-day Aleja Wyzwolenia), the Supreme Audit Office (the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has its office there now) and the Ministry of Public Education and Religion at Aleja Szucha. The proximity of the Belvedere and the Main Inspectorate of the Armed Forces (the Prime Minister’s Office is located there at present) also made an impact. In 1935, when Poland bade farewell to Marshal Józef Piłsudski, ideas appeared for commemorating him through urban development. One of the ideas was to delineate Józef Piłsudski avenue running westwards along King Stanisław Axis (more or less on the axis of the present Łazienkowska thoroughfare), which was expected to be the main road of a district named after Piłsudski. According to the plans, the buildings along it were to be in the monumental modernism style. The planned avenue would begin with a Józef Piłsudski monument, which was to be erected at Plac Na Rozdrożu, which was renamed Plac Wolności in 1938. These plans were thwarted due to the outbreak of World War II in September 1939.

The elite housing cooperatives

The ‘turnpikes’ of the tenement houses at Koszykowa

can be seen. NAC

The prestigious surroundings of Plac Na Rozdrożu towards the end of the 1920s were appreciated by developers. The construction of the sister buildings, 6 and 6a Koszykowa, was completed in the early 1930s. The characteristic corner finials, the terrace along the top floor and the geometric twists on the facades typical of the art déco style emphasised the exceptional nature of both buildings. These buildings, as well as the building which currently serves as the headquarters of the Ministry of Justice, were designed by the famous Warsaw-based architect, Adolf Inatowicz-Łubiański. He was born in 1892 in Kherson Governorate. Having received his education as an architect at the technical university in Riga, he studied painting in Kiev and in 1920 he fought as a volunteer in the Polish-Bolshevik War. In the late 1920s/early 1930s, he became a popular architect.

What is now the headquarters of OSW was built by the limited company named Żelazo-Beton, whose achievements in the construction sector included a number of military facilities (for instance, the Polish Navy’s torpedo warehouse in Gdynia).

The buildings were managed by the cooperatives Kresowa (4-6 Koszykowa) and Idealna (6a Koszykowa). According to Jerzy Kasprzycki, an expert in the history of Warsaw, an important role in the cooperatives that developed the buildings was played by Julia Mazaraki, a land owner originating from the eastern borderland of Poland known as Kresy and an activist of the cooperative movement. “A tenant in the buildings erected under her patronage had to be someone. Money was not enough – you had to have a proper name, social position and influential friends. One of the residents of the front building at Aleje Ujazdowskie with a side wing on Koszykowa was Jerzy Paczkowski, a poet and satirist popular in pre-war Warsaw, editor of the satirical literature weekly, Cyrulik Warszawski, author of satirical texts for cabarets and theatres, whose sharp tongue mercilessly mocked dignitaries of the time.” One proof of the tenement house’s status was the lease offer , which contained the provision: ‘only for those with a position.’

The luxurious standard of the buildings for that time and the careful selection of tenants also attracted representatives of the Soviet diplomacy. And this is where the OSW’s genius loci is manifested. The Soviet trade mission had its seat on the ground floors of the twin tenement houses in the 1930s. It was engaged in intense trade activity, such as offering agency services in the sale of fur coats. In 1934 this location served as the setting of a crime story, the main protagonist of which was named Wacław Syropol.

A characteristic feature of the immediate surroundings of 6a Koszykowa is the lack of a courtyard. The internal space between the neighbouring buildings is Warsaw’s shortest street, named after Saint Theresa. According to Tomasz Urzykowski’s description (‘Wokół Placu Na Rozdrożu’, Spacerownik Warszawski 2008), the press reported the emergence of the street in August 1931 (a driveway of around 50 metres in length that emerged during the construction of the tenement houses). “Our city has recently gained a tiny new street. Two large residential blocks of flats have been built at 2 and 4 Koszykowa by housing cooperatives. These blocks form a short street which has been named św. Teresy.” This happened in 1927, when allotment of the land adjacent to Koszykowa was carried out. The street was treated as a driveway to the houses built by the housing cooperatives Kresowa and Idealna.

The Nazi occupation

The building at 6a Koszykowa was left intact after the siege of Warsaw in September 1939. Its condition was captured in a picture made by an anonymous German photographer who was documenting the removal of the barricade across Koszykowa by residents of the buildings in the neighbourhood.

In 1942, members of the cooperatives managing the tenement houses finally repaid the loan granted for their construction. The fact that Polish residents of the buildings were forced to leave the buildings in the same year can be viewed as a bitter irony of history. Their presence became undesirable in the area where Nazi security institutions were located. Along with the infamous Gestapo headquarters at Aleja Szucha, the central headquarters of Criminal Police were located in the immediate neighbourhood. The flats were taken over by Nazi officials and officers of law enforcement agencies and individuals who were trusted by the occupation authorities. The name of the street was also changed. Koszykowa became Kurt Lück Strasse (the short-lived patron was an ethnographer originating from Chodzież, an SS officer subsequently killed by Belarusian guerrillas near Orsha, who was engaged in strengthening German influence in the territory of interwar Poland,). However, the new residents did not enjoy a quiet life there. On 1 October 1943, a unit of the Home Army staged a successful attack on a resident of the building at 6 Koszykowa, Ernst Weffels, a shift supervisor in the women’s section of Pawiak Prison, who was known for his extreme brutality.

The Warsaw Uprising

In August 1944, 6a Koszykowa was out of reach of the insurgent troops who held the front line along Mokotowska street and a fragment of Aleja Róż. The building was controlled by police units of the SD (Sicherheitsdienst, the intelligence agency of the SS), which took part at the beginning of September 1944 in the brutal displacement of civilian residents from the area around what now is Aleja Wyzwolenia.

In the ‘People’s Poland’

Na Rozdrożu. The inscription ‘Ruch’ can be seen on the

building at 6a Koszykowa. 1979. Fotopolska

The tenement house, which had suffered only minor destruction, was taken over by the state in 1945. The building was granted the status of a public institution building (the ‘public utility’ of the Nazi security authorities was recognised without provoking any major distaste). This opened up the way for another dark chapter in the building’s history. It was left at the disposal of the Ministry of Public Security.

Św. Teresy street became the internal courtyard of the ministry, from which ‘enemies of the system and the state’ were led into the underground cells. 6a Koszykowa became a fragment of the closed area at the disposal of officers of the security services. They lived here, with the ministerial kindergarten and canteen available for their use, and enjoyed access to nearby shops that were reserved for the members of the communist elite. This situation continued until 1954, when public security officials moved to the new building on Rakowiecka street. The tenement house was handed over to civilian institutions. The editorial offices of the publishing houses that were part of the ‘socialist press corporation’, RSW Prasa-Książka-Ruch, stayed there longest of all, until 1990. The Central Customs Office was located on the lower floors of the building for some time. In December 1990, the Centre for Eastern Studies began writing a new chapter in the history of 6a Koszykowa.

The present look of the building on the outside and the headquarters of OSW

We have made all possible efforts to obtain the rights to publish all the photographs above. Possible authors or copyright owners are requested to contact us so that we can make a correction.