Smartphones on wheels

I. CONNECTED CARS: CHINA’S PERSPECTIVE

II. WHAT CARS KNOW: DATA COLLECTED BY CONNECTED VEHICLES

III. WHAT RISKS DO CARS CREATE: THE CYBERSECURITY OF CONNECTED VEHICLES

IV. WHAT THIS MEANS FOR EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

1. What Europe can learn from China’s regulations

2. The current state of play – and what the EU should do next

INTRODUCTION

The rapid influx of Chinese intelligent and connected vehicles (智能网联汽车; Intelligent and Connected Vehicles; ICVs) across Europe is transforming mobility – and raising new cybersecurity questions. These cars come equipped with connectivity technologies that enable scanning, geolocation, communication with infrastructure, and remote real-time services. They also enable expansive data collection – including geospatial and personal data. While every major carmaker is now racing to develop and deploy these capabilities, the People’s Republic of China is emerging as the global leader. In 2025, Chinese automakers sold about 810,000 vehicles in Europe – up 99% year-on-year – lifting their market share to 6.1%.[1]

Beijing’s warning label

Chinese state bodies themselves increasingly frame connected cars as a fundamental national security risk. They emphasise the danger of state secrets being leaked, the collection of data on critical infrastructure and military facilities, and the transfer abroad of sensitive information about how the economy and society function. The main risks include:

- exposure to cyberattacks (for example, the remote takeover of vehicles or disruption of their sensors could cause serious accidents);

- the harvesting of sensitive data about the vehicle’s surroundings (for example, about critical infrastructure);

- the extraction of data from inside the car (for example, conversations or drivers’ and passengers’ biometric data).

The Chinese regulators also point to the risk of exporting insights derived from analysing datasets from millions of vehicles. This could enable, for instance, estimates of traffic volumes around military units, proxies for economic activity, or, via the mass scanning and facial recognition of passers-by, and broader forms of surveillance.

China’s playbook: regulate, restrict, certify

China’s response has been to build a comprehensive regulatory system for connected vehicles. It includes, among other measures, restrictions on data deemed important for national security and sensitive personal data collected by vehicles operating on Chinese roads being sent abroad. Chinese policy discussions have proposed a one-click mode to disable off-vehicle data collection in areas considered sensitive for national security.

For foreign manufacturers, Beijing has gone further: it makes access to certain parts of China conditional on passing an advanced data security certification process. Until recently, Tesla vehicles operating in China were subject to informal restrictions on driving and parking in sensitive areas – including near government buildings, certain airports, and motorways, as well as locations hosting events attended by senior Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders, including Xi Jinping. Tesla cars produced in Shanghai since 2019 underwent certification in 2024, following a series of Chinese data-security tests.

These steps are part of a broader state strategy: China is constructing regulatory tools to ensure that connected vehicles are used domestically in line with the state interest as defined by the CCP. In parallel, Beijing is pushing to deepen integration between connected cars and technologies with potential military applications – including the BeiDou satellite navigation system.

Defensive rules today, offensive potential tomorrow

While China’s current approach is defensive, it could in time choose to use the technology’s potential more offensively. Given the scope and sophistication of China’s domestic regulatory framework, its advanced offensive cyber capabilities, its mature intelligence ecosystem and strategic guidance on civil–military integration in the development of connected cars, this possibility cannot be ruled out. This would be especially true in a crisis and, most of all, in a wartime scenario.

That creates a clear need for the rigorous scrutiny of connected vehicles, including for the scanning of critical infrastructure via their sensors, the collection of sensitive information, and cyber vulnerabilities. This matters even more in light of the deepening China–Russia alignment and the risk that data gathered today by connected cars on European roads could ultimately be shared with the Russian Federation. Moreover, connected vehicles – regardless of the manufacturer’s country of origin – are also vulnerable to cyberattacks and, given their remote-control capabilities, could be repurposed for sabotage.

Europe’s gap and a policy opportunity

The EU lacks a comprehensive legal framework governing the operation of connected cars. And this is a breakthrough technology that requires detailed, enforceable rules – including to prevent the automatic transfer of sensitive data abroad and to reduce cyber risks.

China’s own regulatory approach can serve as a useful starting point for understanding the risks associated with connected cars – and, indirectly, for building a legal environment that limits them. Using Chinese documents as a reference point for “good practice” would also strengthen the EU’s hand politically: it would help European governments to justify tighter rules on Chinese connected vehicles to Chinese officials, by using Beijing’s own logic as precedent. Moreover, tougher regulation – for example, requirements to rely on European IT solutions – could double as industrial policy, pushing Chinese firms to locate value-added advanced services inside the EU.

About the report

The growing popularity of Chinese cars has reignited European debates about the cybersecurity risks that may come with them, from sensor-rich vehicles being exploited for espionage to the possibility that connected cars could be repurposed for sabotage. A frequent point of reference in these discussions is the regulatory and risk-assessment frameworks which have been adopted elsewhere, notably in the United States, the United Kingdom and Israel.

But Europe is overlooking an obvious comparison: China itself. China has built one of the world’s most extensive systems of regulation and standard-setting for connected vehicles. Chinese state institutions openly point to the wide range of cybersecurity threats associated with these cars – and they do not hesitate to exercise control over foreign manufacturers operating on Chinese roads, including Tesla.

This report maps China’s regulatory ecosystem for connected cars. It offers an insight into how the Chinese authorities think about this technology – and provides a useful starting point for European policymakers who are considering whether, and how, to build comparable rules at home.

The main goal of this report is to show how China defines connected cars – both as a source of strategic opportunities and as a potential threat to national security. The analysis reviews selected regulatory frameworks developed by the Chinese authorities to manage these risks.

The study draws on Chinese-language (Mandarin) documents published by China’s central and local institutions, including ministries, regulators, standard-setting bodies, and local governments. It covers both legally binding acts and drafts of regulations and standards that signal the direction of future policy. The report is not comprehensive and cannot capture every relevant document issued by the Chinese authorities – in part because of the closed nature of China’s internet ecosystem. All materials used are drawn from open sources.

I. CONNECTED CARS: CHINA’S PERSPECTIVE

In China, the automotive industry is treated as a strategic pillar of the country’s technological future. Connected vehicles have been important for Beijing since 2015. They feature in China’s flagship industrial strategy, Made in China 2025, as a key pathway for modernising the country’s car industry.[2] The growth of the intelligent transport sector is also embedded in China’s 14th Five-Year Plan for 2021–2025 as a development priority.[3]

Chinese state bodies point to the sector’s strategic importance:

The development of connected vehicles helps enhance fundamental industrial capabilities, break through key technological bottlenecks, strengthen the ability to lead a new round of scientific and technological revolution and industrial transformation, and foster new competitive advantages for industrial development.[4]

Connected vehicles are, for China, not only the future of the automotive industry but also a building block of military power. In Beijing’s view, this technology does not belong solely to the civilian sector: it is also intended to strengthen China’s defence capabilities. This aligns with Xi Jinping’s civil–military fusion (军民融合) – the policy designed to remove barriers between civilian research and the defence industrial base, with the ambition of building a technologically advanced armed forces. From China’s perspective, the BeiDou satellite navigation system is particularly significant in this realm. On the one hand, it enables high-precision navigation services for connected cars; on the other, it is strategically important for the military operations of the People’s Liberation Army.

As the National Development and Reform Commission, together with ten other state bodies, argues in the “Connected Vehicle Innovation Development Strategy”:

[Our main tasks include] … promoting the transformation and application of new technologies, including carrying out joint military–civilian R&D efforts and accelerating the application of the BeiDou satellite navigation and positioning system and high-resolution Earth observation systems in connected-vehicle–related fields.[5]

As China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology puts it:

[China needs to] support the construction of the BeiDou satellite navigation system and facilities such as differential base stations, raise the level of the large-scale deployment of high-precision spatiotemporal services for vehicles, and meet vehicles’ needs for high-precision positioning and navigation.

[China should] promote the establishment of a data-sharing mechanism for connected-vehicle base map data and satellite remote-sensing imagery data.[6]

China’s push to develop connected vehicles goes hand in hand with growing national security concerns. In official documents, these risks are typically framed in two ways:

- Connected vehicles increase exposure to cyberattacks – for example, remote takeover or interference with sensors could trigger serious road accidents,

- Connected cars collect sensitive data both from their surroundings and from inside the vehicle (such as information related to critical infrastructure, or drivers’ and passengers’ biometric data), creating a larger surface for intelligence exploitation.

According to the Standardization Administration of China:

As a means of transport used in people’s daily lives, connected vehicles have an inherent advantage in acquiring and aggregating geographic information data on a wide scale, over long periods, and at multiple levels. The massive volume of geographic information data obtained can be used for military intelligence analysis, assessments of critical military and civilian facilities, and analyses of activity patterns in major military and economic operations, thereby posing potential risks to national security.

Chinese documents also highlight the significant risk of state secrets leaking:

Connected vehicles’ acquisition – via onboard sensors and systems – of geographic information data about the vehicle and its surroundings constitutes surveying and mapping activity as defined in Article 2, Paragraph 2 of the Surveying and Mapping Law of the People’s Republic of China.

The high-precision geographic information data obtained through these activities – such as spatial location data, point clouds, and imagery – fall within the category of “measured results” specified in the Provisions on the Scope of State Secrets in Surveying and Mapping Geographic Information Management Work (自然资发〔2020〕95号). Specifically, this includes measured outputs such as 3D models, point clouds, oblique imagery, real-scene imagery and navigation electronic maps that: have planimetric accuracy better than (or equal to) ten metres or relative feature-height measurement accuracy better than (or equal to) 5%, are outside military prohibited zones, and continuously cover an area exceeding 25 square kilometres. Such measured outputs constitute state secrets.

China currently lacks the corresponding mandatory standards and management systems to regulate data-processing activities in connected-vehicle surveying and mapping sensing systems. Problems such as the illegal collection, illegal storage, and illegal cross-border transmission (to overseas destinations) of geographic information data exist, making it highly likely that state-secret data could be leaked.[7]

The risk discussion also extends to cyberattacks and remote takeovers of vehicles. These concerns are explicitly reflected in documents issued by Industry and Information Technology Bureau of Shenzhen Municipality – Shenzhen has emerged as one of China’s key testing grounds for autonomous driving, backed by a dedicated local regulatory framework and designated pilot areas:

As vehicles become increasingly intelligent and connected, people are able to exercise greater control over their cars, bringing various conveniences to daily life. However, the accompanying security risks – such as remote attacks, data leaks, and even connected vehicles being taken over – are becoming increasingly apparent.[8]

Connected vehicles produced by foreign manufacturers have been explicitly identified as a national security threat by the Standardization Administration of China:

In particular, the widespread use and promotion of vehicles made by foreign manufacturers and brands across the country has brought potential and incalculable security risks to China’s geospatial information security and national security.[9]

As the automotive revolution unfolds, so too does China’s regulatory and technical standard-setting system for connected cars. Two laws provide the backbone of this approach: the Cybersecurity Law (2017) and the Data Security Law (2021). Together, they impose a broad set of obligations on manufacturers – including requirements to store key data inside China (with any transfer abroad subject to approval by the Cyberspace Administration of China); to implement security management systems; to classify data according to its importance, including to the state; and to conduct risk assessments and report to regulators.

Chinese state bodies argue that connected vehicles are a disruptive technology and therefore require the regulatory framework to be continually updated:

As a typical representative of the new round of scientific and technological revolution and industrial transformation, connected vehicles are developing rapidly; however, the rapid advances in automotive technology have also highlighted a lag in the laws, regulations, policies, and standards related to connected vehicles’ cybersecurity and data security.

Therefore, there is an urgent need to formulate relevant laws, regulations and standards, to strengthen supervision and management and to safeguard China’s geospatial information security and national security.[10]

Accordingly, China is gradually reinforcing its legal framework for connected vehicles by relying on administrative regulations and technical standards – regulatory instruments that can be revised rapidly in step with technological developments. This is overseen by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and the Standardization Administration of China. The National Technical Committee of Auto Standardization is under their remit, including its TC114/SC34 subcommittee on Intelligent and Connected Vehicles (全国汽车标准化技术委员会智能网联汽车分技术委员会编号TC114/SC34). The subcommittee brings together 72 experts, mostly drawn from the automotive sector.[11]

Local authorities also play an important role, developing regional, non-binding technical standards for companies. Shenzhen stands out in this respect. As one of China’s key innovation hubs, the city has produced a range of local technical standards for connected cars – some of which directly impinge on state security priorities, including data protection and cybersecurity.

However, China has gone further than codifying rules: it has built an additional data-security certification regime designed to test connected car manufacturers in practice. Since 2024, this work has been carried out by the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM; 中国汽车工业协会) and the China’s National Computer Network Emergency Response Technical Team/Coordination Center (CNCERT/CC; 国家计算机网络应急技术处理协调中心). [12] The tests assess:

- Anonymisation of facial and other information from outside the car: the effectiveness of anonymising both facial data and data captured from the vehicle’s surroundings is tested (including pedestrians’ faces and other vehicles’ licence plates). The vehicle’s system must detect at least 90% of faces and licence plates in the data (photos and video recordings) and then anonymise them.

- In-vehicle processing of cabin data: In-cabin personal data may be shared with third parties only if the data subject (for example, the driver) has given consent. For instance, if voice commands must be processed off-board to enable real-time recognition of vehicle control instructions, the vehicle must obtain the data subject’s consent and – once the function is completed – immediately delete both the raw voice-command data and the processing results. Likewise, features such as remote viewing or cloud storage that make data available to the user must operate on the basis of consent and include measures that prevent access by unauthorised persons.

In the selected test environment, the vehicle must not provide any other in-cabin data to external parties. The direct transfer of personal data abroad is also prohibited. - The default non-collection of in-car data: the test checks that the vehicle does not gather in-cabin personal data unless the driver explicitly enables this. By default, personal information collection must be switched off unless the driver changes the setting. Any processing of personal information must be based on consent, and sensitive personal information must require separate, explicit consent.

Users must be able to choose a time limit for sensitive-data consent and be given clear options to agree or refuse; consent cannot be set to “always on” or indefinite. The vehicle must also provide an easy way to withdraw consent, and withdrawal must not invalidate any processing that lawfully occurred before it. Where it can be done without compromising driving or personal safety, stopping in-cabin image/video collection should also turn off the in-cabin cameras or other image capturing hardware.

The system must offer a way to delete in-cabin data stored on the vehicle, and if an individual asks for the deletion of sensitive personal information, it must be erased within ten working days.

- The conspicuous notification of personal information processing: the test checks that individuals are clearly informed – through at least one highly visible method – about when and why their personal data are being processed, and that they are given easy-to-use, interactive tools to manage that data. The vehicle must provide an explanation of the specific processing context and necessity, and provide conspicuous entry points (which are easy for the data subject to notice) to functions that allow the user to view, copy, and delete their personal information.

The notice and controls should cover, at a minimum: the categories of personal information processed and why each category is necessary (including the purpose, use, and processing method); the situations in which each category is collected and how the user can stop collection; where the data are stored and for how long (or the rules used to determine storage location and retention period); how the user can view and copy their data, delete data stored in the vehicle, and request the deletion of data that have already been provided outside the vehicle; the name and contact details of the person responsible for handling user rights requests; and any other disclosures required by laws and administrative regulations.

In addition, if the vehicle data processor continuously collects sensitive personal information, the vehicle must provide a clear, ongoing status indication – such as an in-vehicle display icon or a flashing/steady indicator light. The indication must be easy to understand and clearly differentiated depending on the type of information being collected. - Precision- and range-appropriate data collection: the test checks whether the vehicle’s sensors collect personal data only at the level of precision and within the coverage area necessary to deliver the relevant function. For example, if a feature only needs to detect obstacles, the vehicle’s cameras should not capture footage at a resolution that would make it possible to identify pedestrians’ faces near the car.

When collecting personal information, the vehicle data processor must set parameters such as the coverage range and resolution of cameras, radar, and similar sensors in line with the data-accuracy requirements of the services provided.

The precision- and range-appropriate collection test is the newest element of the CAAM’s data security testing: earlier CAAM notices focused on four requirements, while the five-requirement framework was published in August 2025.[13]

Producing its cars in Shanghai since 2019, Tesla is the first non-Chinese (US) automotive company to obtain a data security certification from China’s authorities. A positive assessment was issued in April 2024 and covered two models: the Tesla Model 3 and the Tesla Model Y.[14]

Officially, participation in data security tests is voluntary and open to both domestic and foreign manufacturers.[15] Before receiving the certification, however, Tesla cars were subject to informal restrictions on driving and parking near locations considered sensitive for state security – such as government institutions, military facilities, some airports and motorways – as well as places where events involving key Chinese Communist Party representatives were planned, including Xi Jinping.[16] These restrictions remained in place even though Tesla had already launched a data centre in Shanghai in 2021 to comply with rules on the local storage of data generated in China.[17] Tesla stated that the reason for obtaining the data security certification is to allow its vehicles broader access to the locations mentioned above.[18]

Chinese companies that have so far obtained certification for selected models include: BYD, Li Auto, Lotus, Hozon New Energy, NIO, Chongqing Changan, SAIC, Chery, Geely, Great Wall, XPeng and FAW-Volkswagen.[19] Many already operate in Europe or are preparing to enter the market soon.

Picture. Tesla vehicles in China were subject to informal restrictions in sensitive areas

Source: Weibo account of China Newsweek; Yueyang Airport “bans Teslas from entering”; Changsha Airport and Changsha South Railway Station have no similar rule (岳阳机场“禁止特斯拉入内”,长沙机场、长沙南站没有类似规定), 15 August 2023, hengyang.gov.cn.

Translation of the text above the picture:

On August 12 in Yueyang, Hunan, some internet users reported that a notice had been posted in the parking lot of Sanhe Airport reading: “Confidential controlled area. Teslas may not enter”.

On August 13, staff answering the airport’s complaints hotline said the parking lot does indeed have such a notice and that Tesla vehicles are prohibited from entering. They added that the notice has been in place for several months. If Tesla owners need to park, they can drop passengers off at the airport and then park outside the airport – turning right at the intersection outside.

That same day, staff answering the airport police hotline also confirmed that this notice was on display. The reason given was that Tesla vehicles have a certain mode that records video of the environment around the car after the owner leaves. The staff member said many organizations now prohibit Teslas from entering, and even Teslas owned by airport employees are not allowed in.

II. WHAT CARS KNOW: DATA COLLECTED BY CONNECTED VEHICLES

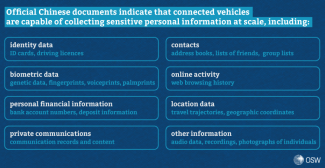

Equipped with radars, sensors, high-resolution cameras, precision maps, and global navigation satellite systems (GNSS), connected vehicles can observe, record, and analyse data from both the vehicle’s surroundings and its interior. Chinese state documents map these data types – and outline how the authorities expect them to be governed.

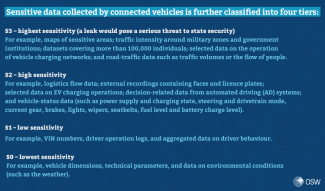

Chinese documents define “sensitive data” as data of critical importance to national security. This category includes:

- data on geospatial information, as well as flows of people and vehicles in sensitive areas – such as military management zones, defence and scientific-industrial facilities, and party and government bodies at the county level and above;

- data relating to traffic volumes, logistics, and other indicators of economic activity;

- data on the operation of electric-vehicle charging networks;

- video and photos from a vehicle’s external cameras containing faces and vehicle licence plate numbers;

- personal data relating to more than 100,000 individuals;

- other data designated by the national information and communications authorities and relevant state bodies – including the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the Ministry of Public Security, and the Ministry of Transport – as critical to national security, the public interest or the lawful rights and interests of individuals.[20]

Source: Requirements of data security for intelligent and connected vehicles (智能网联汽车数据安全要求), Market Regulation Bureau of Shenzhen Municipality, 22 August 2023, sz.gov.cn.

China’s rules set out clear principles for handling sensitive data:

- domestic storage: sensitive data collected by connected vehicles in China should be stored inside the country. The authorities have called for testing to verify that these data are not being transmitted beyond China’s borders. If a business needs to transfer sensitive data generated in China abroad, the data controller may do so only after securing a Cyberspace Administration of China security assessment.

- data minimisation: the scope and resolution of cameras, radars, and other sensors must be proportionate to the services provided;

- access control: the use of sensitive data must be protected by safeguards that prevent unauthorised access;

- irreversible deletion: once deleted, sensitive data must be impossible to recover;[21]

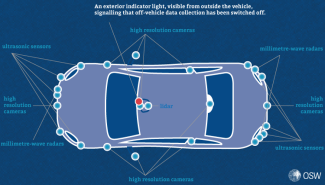

- a one-click mode to disable off-vehicle data collection: Chinese standard-setting bodies propose equipping connected cars with a one-click mode that halts the collection of data from outside the car – by switching off sensors, cameras, radars, LiDAR and other systems. When this mode is activated, the vehicle cannot collect information about roads, buildings, terrain, licence plates or other road users. Crucially, switching to this “data-off” mode should be visibly indicated on the exterior of the vehicle – so that e.g. the authorities tasked with protecting sensitive sites can readily identify it.[22]

Figure. In “data-off” mode – when off-vehicle data collection is disabled – high-resolution cameras, LiDAR, radar, sensors and other relevant systems in a connected car are switched off. “Data-off” mode is visibly indicated on the exterior of the vehicle

Source: Own work based on Cybersecurity Standards: a Practical Guide. Guidance on “One-Click Stop” for Collecting Off-Vehicle Data (网络安全标准实践指南– 一键停止收集车外数据指引), National Technical Committee 260 on Cybersecurity of Standardization Administration of China, June 2024, tc260.org.cn.

Equipped with cameras, infrared sensors, fingerprint scanners, and microphones, connected vehicles can capture virtually every movement and utterance of the driver and passengers – and, in some cases, of people in the vehicle’s immediate vicinity.

Under Article 4 of China’s Personal Information Protection Law, this information qualifies as personal data.[23] Chinese standard-setting documents place particular emphasis on:

- sensitive personal data collected by connected cars – including information on travel routes, audio and video recordings, photographs, and biometric data;

- in-cabin data collected inside connected vehicles – data gathered through cameras, infrared sensors, fingerprint scanners, and microphones, which may include personal data as well as information generated by processing them.[24]

China’s approach to personal data processing in connected vehicles rests on a set of practical rules:

- domestic storage: when dealing with personal data which are collected by connected cars in China, the vehicle data processing entities are required to store these data in China. Where data must be transferred abroad, the controller should apply to the Cyberspace Administration of China for a security assessment of the transfer;

- privacy by default: unless the driver changes the settings, vehicles should not collect personal data or transmit it beyond the vehicle;

- user consent: processing personal data requires the consent of the car’s owner or driver. Before collection begins, the user must receive clear information on the types of data collected, the purpose and method of processing, the location and duration of the data’s storage, and the controller’s contact details.

Users have the right to withdraw consent at any time; vehicle systems should make this easy, and manufacturers are required to provide the necessary functionality. In emergencies – for example, to protect life and health – and to ensure road safety, data may be processed without the owner’s or driver’s consent;

- anonymisation: visual data containing faces and licence plates must be anonymised before being transmitted outside the vehicle. The anonymisation process is subject to strict testing: the detection of objects requiring anonymisation (faces and licence plates) must reach at least 90%, while false identifications must not exceed 10%;

- data deletion: personal data should be erased once the processing purpose has been achieved, consent has been withdrawn, or service provision has ended. Users may request deletion, and the processor must comply within ten working days;

- access control: data must be protected against unauthorised access. Driver/owner identification functions in the vehicle may not rely solely on biometric data.[25]

III. WHAT RISKS DO CARS CREATE: THE CYBERSECURITY OF CONNECTED VEHICLES

Connected vehicles rely on multiple channels that expose them to potential cyberattacks. Manipulating sensor signals, disrupting V2X (vehicle-to-everything) communications – which allow vehicles to interact with road infrastructure, other vehicles and road users – or remotely taking control of key vehicle functions could trigger collisions, paralyse transport infrastructure, and cause large-scale road incidents.

China’s cybersecurity rulebook for connected vehicles is designed to shield them from hostile third-party activity – including hacking and offensive cyber operations. China’s provisions include:

- limits on cross-border data transfers: the direct transmission of vehicle data abroad is prohibited.

- a vehicle cybersecurity management system: manufacturers must implement a cybersecurity system covering the vehicle’s entire lifecycle – from design and production to operation and decommissioning. This system should include risk identification and assessment, the monitoring of threats and vulnerabilities, and incident-response procedures.

- securing external interfaces: vehicles should not ship – or operate – with unpatched high-risk software flaws, and any unused communication ports should be kept closed. Third-party apps must be vetted for their integrity, with unauthorised software blocked or tightly limited. The same logic applies to physical access points, such as USB and diagnostic ports, which should be protected via access controls, anti-malware measures, and authentication for any attempt to alter critical vehicle settings. Where remote control is possible, commands must be verified for authenticity and integrity, and the vehicle should maintain robust security logs.

- cloud and V2X channels: connections to a manufacturer’s cloud should run on secure protocols (such as TLS 1.2). V2X systems are expected to use certificate-based authentication and to safeguard data integrity. Inside the vehicle, networks should be segmented into security zones. And the software should be able to spot and resist denial-of-service attacks, while detecting and stripping out malicious data embedded in V2X traffic or other messages.

- software update security: update systems should support secure booting, protect firmware integrity, and be free of known high-risk vulnerabilities. Both over-the-air (OTA) and offline updates must be verified for authenticity and integrity. The update process should be monitored and logged, particularly where there have been failed attempts.

- protecting data and code: manufacturers are required to store cryptographic keys and authentication credentials securely – ideally in dedicated hardware security modules (HSMs). Personal data and other sensitive information must be shielded from unauthorised access through encryption and access controls. Critical vehicle parameters – such as brake-system configurations or airbag deployment thresholds – receive particular protection and cannot be altered or deleted without authorisation. Vehicles should also support the secure deletion of personal data and prevent its recovery – this is especially important when a vehicle is resold or scrapped.[26]

IV. WHAT THIS MEANS FOR EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

So far, China has approached connected vehicles largely defensively, building an expanding regulatory toolkit to protect itself against unauthorised data collection and cyber risks to vehicle systems. But Beijing could, over time, also choose a more offensive posture. China’s domestic regulatory framework, its advanced offensive cyber capabilities, its mature intelligence ecosystem, and strategic guidance on civil–military integration in the development of connected cars is of such a broad scope and high sophistication that this possibility cannot be ruled out – especially in a crisis – and, most of all, in a wartime scenario. At a minimum, the logic and breadth of China’s domestic rules, and its own official risk assessments, underline one central point: Beijing treats connected vehicles first and foremost as a security technology, not just a consumer product.

Under Article 7 of China’s National Intelligence Law – and through a range of informal levers – Chinese carmakers could, in principle, be compelled to support and cooperate with state intelligence work, potentially including by handing over data held abroad.[27] As a result, data collected in Europe by Chinese-made connected vehicles could be repurposed for intelligence purposes – from tracking individuals and goods flows to mapping mobility patterns – and for training AI systems, including with potential military applications.

Some research initiatives and media reports suggest the privacy and security risks related to the Chinese-made vehicles are not merely theoretical. For example, the “Lion Cage” research initiative led by Norwegian engineer Tor Indstøy highlighted how data flows to and from a Chinese-made electric vehicle as a potential area of concern. In the analysis, about 90% of the car’s outgoing communications — covering data ranging from basic voice commands to location information — were transmitted to China.[28] Moreover, in 2023, British news outlets reported the discovery of a suspected Chinese tracking device in a UK government vehicle – an episode that has since been repeatedly cited in the UK debate about exposure to Chinese-linked surveillance.[29] This underlines the case for the especially rigorous vetting of connected cars, including for the use of their sensors to scan critical infrastructure and to harvest other sensitive information.

This matters most acutely for NATO’s eastern flank, given the deepening China–Russia relationship and the risk that data gathered by Chinese connected vehicles on European roads could ultimately be shared with the Russian Federation.

But policymakers should also keep a broader point in view: connected vehicles, regardless of their country of origin, are inherently exposed to cyberattacks and to the exploitation of their sensors for intelligence purposes – and, where remote control is possible, even to acts of sabotage.

For that reason, thinking about regulation across Europe should go beyond threats specific to China. It should also be used to raise cybersecurity standards for the entire market, tightening requirements for all manufacturers operating in the European ecosystem.

China’s approach offers a useful starting point for understanding the risks associated with connected vehicles – and, indirectly, for designing a regulatory environment to contain them. For instance, Chinese regulators stress that connected cars can collect and transmit abroad geospatial data from sensitive areas, including data related to critical infrastructure – with the potential to expose state secrets. Beyond risk categorisation, Chinese documents also provide templates for certifying car manufacturers and for diagnosing and verifying whether data are being sent overseas and what these data are. They also point to specific technical safeguards – such as a one-click mode to disable off-vehicle data collection in areas considered sensitive for national security – making it easier for the state services to determine when a car is actively harvesting data. Taken together, these measures are not only a practical set of “good practices”. For the EU, drawing on them would also provide a political argument: it would help European governments or the EU justify any decision to tighten the rules on Chinese connected vehicles by pointing to Beijing’s own logic and precedents.

Beijing’s treatment of foreign manufacturers such as Tesla illustrates how cautiously and restrictively China approaches non-domestic players. This includes the state-led data-security certification of connected cars, alongside requirements to store vehicle-generated data locally, inside China. In practice, meeting these conditions is a prerequisite for operating smoothly in the Chinese market.

For the EU, China’s certification model offers a ready-made template: it could help raise baseline vehicle cybersecurity, strengthen digital sovereignty and support trusted European suppliers in sectors such as IT services, data processing, AI and autonomous driving.

The need to put connected vehicles on a clear regulatory footing in Europe is becoming urgent, not least because the number of Chinese-made cars on the EU market is rising sharply. Europe remains one of the most attractive destinations for Chinese carmakers, and both imports and local production are likely to expand significantly in the coming years. Even after the EU introduced anti-subsidy duties on Chinese battery electric vehicles (BEVs), their level (17–35.3%, plus the EU’s 10% common external tariff) remains relatively modest compared with the trade policies of other countries, such as the United States, where tariff rates reach 100%.[30]

At the same time, some Chinese manufacturers are cushioning the impact of EU duties by shifting exports towards plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) and internal-combustion models, which are not subject to the EU’s additional levies.[31] Crucially, the “digital layer” is no longer an EV-only feature: vehicles across all powertrains are now becoming connected, sensor-rich and software-defined. Europe should therefore expect that, as the stock of Chinese-made connected cars grows, consumer resistance to new rules – and the political cost of regulation – will rise in parallel.

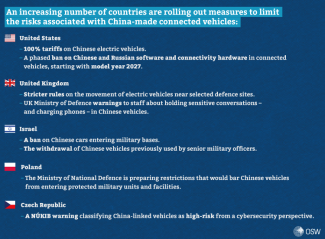

A growing number of countries are taking steps to curb the national security risks associated with connected cars from China. The United States is leading the way: in 2024, invoking a national security clause, Washington adopted rules that introduce a phased ban on the use of Chinese and Russian software and communications hardware in new cars. The measures will be rolled out gradually for model year 2027 vehicles and beyond.[32]

In the United Kingdom, some defence institutions have introduced stricter requirements governing the movement of electric vehicles near selected sites.[33] The British media has also reported that the Ministry of Defence has warned staff against holding sensitive conversations inside cars, amid concerns over Chinese espionage.[34] Media reports further suggest that Israel has barred Chinese cars from entering military bases and withdrawn Chinese vehicles used by senior officers.[35] Poland’s Ministry of National Defence press services confirmed that preparations were underway to limit the entry of Chinese-manufactured vehicles to protected military areas.[36]

The Czech Republic’s National Cyber and Information Security Agency (NÚKIB) has issued a warning classifying the threats linked to the transfer of system and user data as high-risk, as well as the remote administration of technical assets from Chinese territory. The warning identifies connected vehicles as one example of high-risk products and services that may transmit data to China.[37]

There is currently no comprehensive EU framework governing the operation of connected vehicles. So far, European action has taken shape along multiple tracks:

- The European Commission is conducting a cybersecurity risk assessment of connected vehicles in the context of the NIS2 directive.[38] Connected vehicles may also be addressed in the ongoing review of the EU’s 2019 Cybersecurity Act.[39]

- The EU Data Act singles out vehicles as a core category of connected products. It sets rules on both third-country government access to data and on the conditions for international data transfers. Article 32 prohibits the transfer of these data – or making them available to foreign authorities where this would be in conflict with EU law or the law of a member state, unless an appropriate international agreement is in place.[40]

- EU rules on type-approval for motor vehicles require manufacturers of connected cars to comply with design requirements and organisational cybersecurity measures.[41] These binding obligations are complemented by guidance: the EU Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) has issued recommendations on the security of connected and automated mobility,[42] which serve as a reference point for designing and implementing vehicle cybersecurity solutions.

- Manufacturers placing connected vehicles on the EU market must comply with UN regulations on:

- vehicle cybersecurity and cybersecurity management systems (UN R155);[43]

- software updates and software update management systems (UN R156);[44]

- automated lane keeping systems (UN R157).[45] - Where vehicle sensors collect users’ personal data, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) also applies.[46] Meanwhile, the NIS2 directive on securing networks and information systems designates operators of intelligent transport systems as a highly critical sector, imposing obligations that include risk management, board-level accountability for cybersecurity, operational readiness and cooperation across the supply chain.[47]

- Security concerns linked to Chinese vehicles are also increasingly being raised by members of the European Parliament,[48] with them pointing to the UK government’s experience and the findings of Estonian intelligence (among other matters). The UK media has reported that British ministers warned that China could use electric vehicles for espionage.[49] Meanwhile, in its 2024 report, Estonia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (Välisluureamet, VLA), warned of the potential transfer to China of data collected by Chinese electric vehicles operating in Europe, as well as an elevated risk of cyberattacks.[50]

EU rules – and most member states’ national frameworks – still lack detailed technical standards and mandatory audits that would enable the systematic, practical verification of cybersecurity and data protection in connected vehicles. As a result, many governments do not even have the tools to regularly check whether the risks discussed in this report – including those explicitly identified in Chinese documents – are becoming present on EU territory.

Given the foundational nature of the threats posed by connected vehicles, it is essential to introduce instruments: not only for cybersecurity and personal data protection, but also, more broadly, for the EU’s digital sovereignty.

The optimal response would be for the EU to introduce rules requiring car manufacturers to obtain additional security certification. A mechanism of this kind would not only raise the level of protection in the single market, it could also help Europe capture technological know-how and anchor a greater share of value added inside the EU. Done well, this would push back against a growing trend: Europe being reduced to a sales market – or, at best, an assembly line – for products designed and controlled elsewhere, increasingly in China.

If an EU-wide agreement proves to be out of reach – whether because a group of member states blocks it, or because of the prevailing trend in Brussels to favour regulatory simplification – Europe should pivot to a coalition of willing countries prepared to move forwards. That effort should be underpinned by a common EU-level template: a single package of standards, ideally developed by the European Commission, that participating states could transpose in a consistent manner. This would not eliminate fragmentation altogether. But it would contain it – while allowing the states that move first to raise security standards and strengthen technological resilience.

[1] B. Anderson, ‘One in 10 New Cars Sold in Europe Last Month Was Chinese’, Carscoops, 22 January 2026, carscoops.com.

[2] “Made in China 2025” (中国制造2025), State Council of the PRC, 19 May 2015, gov.cn; English-language version: Notice of the State Council on the Publication of “Made in China 2025”, CSET, 10 March 2022, cset.georgetown.edu.

[3] 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China and the Long-Range Objectives for 2035 (中华人民共和国国民经济和社会发展第十四个五年规划和2035年远景目标纲要), State Council of the PRC, 13 March 2021, gov.cn; English-language version: Outline of the People’s Republic of China 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and Long-Range Objectives for 2035, CSET, 13 May 2021, cset.georgetown.edu.

[4] Connected Vehicle Innovation Development Strategy (智能汽车创新发展战略), 24 February 2020, ndrc.gov.cn.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Action Plan for the Development of the Intelligent, Internet-Connected Vehicle Industry (车联网(智能网联汽车)产业发展行动计划), Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the PRC, 25 December 2018, gov.cn.

[7] Basic requirements of security testing for sensing system of intelligent and connected vehicle spatio-temporal data (智能网联汽车时空数据传感系统安全检测基本要求), Standardization Administration of China, 2023, std.samr.gov.cn.

[8] Guidance on the “Technical Requirements for Vehicle Information Security of Intelligent and Connected Vehicles” (智能网联汽车整车信息安全技术要求》解读), Industry and Information Technology Bureau of Shenzhen Municipality, 2023, sz.gov.cn

[9] Basic requirements of security testing for sensing system of intelligent and connected vehicle spatio-temporal data (智能网联汽车时空数据传感系统安全检测基本要求), op. cit.

[10] Ibid.

[11] TC114/SC34 Subcommittee on Intelligent and Connected Vehicles (TC114/SC34 全国汽车标准化技术委员会智能网联汽车分技术委员会), Standardization Administration of China, std.samr.gov.cn.

[12] Notice on the Results of Testing for Compliance with Five Security Requirements for the Processing of Automotive Data, Third Batch (关于汽车数据处理5项安全要求检测情况的通报(第三批)), China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM), 18 August 2025, caam.org.cn.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Notice on the Results of Testing for Compliance with Four Security Requirements for the Processing of Automotive Data, First Batch (关于汽车数据处理4项安全要求检测情况的通报(第一批)),China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM), 28 April 2024, caam.org.cn.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Yueyang Airport has ‘banned Teslas from entering,’ but Changsha Airport and Changsha South Railway Station do not have similar rules (岳阳机场“禁止特斯拉入内”,长沙机场、长沙南站没有类似规定), People’s Government of Hengyang, 15 August 2023, hengyang.gov.cn; Z. Yan, Q. Li, B. Goh, ‘Tesla cars barred for 2 months in Beidaihe, site of China leadership meet’, Reuters, 20 June 2022; ‘Tesla cars barred from some China government compounds’, Reuters, 21 May 2021; ‘Tesla cars banned from China’s military complexes on security concerns’, Reuters, 19 March 2021, reuters.com.

[17] D. Yi, F. Murphy, ‘Tesla Announces New Shanghai Data Center to Allay Concerns’, Caixin Global, 26 May 2021, caixinglobal.com.

[18] D. Ren, ‘Elon Musk in China: Tesla passes data security assessment that could pave way for lifting of bars to its cars’ movements’, South China Morning Post, 29 April 2024, scmp.com.

[19] Notice on the Results of Testing for Compliance with Four Security Requirements for the Processing of Automotive Data, First Batch; Notice on the Results of Testing for Compliance with Four Security Requirements for the Processing of Automotive Data, Second Batch (关于汽车数据处理4项安全要求检测情况的通报(第二批)),China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM), 7 January 2025, caam.org.cn; Notice on the Results of Testing for Compliance with Five Security Requirements for the Processing of Automotive Data, Third Batch.

[20] Several Provisions on the Administration of Automotive Data Security (Trial Version) (汽车数据安全管理若干规定(试行)), Cyberspace Administration of China, National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Ministry of Public Security, and Ministry of Transport of the PRC, 16 August 2021, gov.cn.

[21] Ibid; Basic requirements of security testing for sensing system of intelligent and connected vehicle spatio-temporal data (智能网联汽车时空数据传感系统安全检测基本要求), op. cit.

[22] Cybersecurity Standards: a Practical Guide. Guidance on “One-Click Stop” for Collecting Off-Vehicle Data (网络安全标准实践指南– 一键停止收集车外数据指引), National Technical Committee 260 on Cybersecurity of Standardization Administration of China, June 2024, tc260.org.cn.

[23] Personal Information Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (中华人民共和国个人信息保护法), Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), 20 August 2021, cac.gov.cn.

[24] Requirements of data security for intelligent and connected vehicles (智能网联汽车数据安全要求), Market Regulation Bureau of Shenzhen Municipality, 22 August 2023, sz.gov.cn.

[25] Several Provisions on the Administration of Automotive Data Security (Trial Version) (汽车数据安全管理若干规定(试行)), op. cit.

[26] Technical requirements of cyber security for intelligent and connected vehicles (智能网联汽车整车信息安全技术要求), Market Regulation Bureau of Shenzhen Municipality, 22 August 2023, sz.gov.cn.

[27] National Intelligence Law of the People’s Republic of China (中华人民共和国国家情报法), National People’s Congress, 12 June 2018, npc.gov.cn; English-language version: PRC National Intelligence Law (as amended in 2018), China Law Translate, 27 June 2017, chinalawtranslate.com.

[28] J. Robertson, ‘Probing a $69,000 Chinese Electric Vehicle for Clues on Spying’, Bloomberg, 15 May 2024, bloomberg.com.

[29] M. Ross, ‘Chinese tracking device is ‘discovered inside UK government car’, as senior politician slams Beijing as a ‘systematic’ threat to Britain’s security’, Daily Mail, 6 January 2023, dailymail.co.uk.

[30] ‘President Biden Takes Action to Protect American Workers and Businesses from China’s Unfair Trade Practices’, The White House, 14 May 2024, bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov.

[31] Z. Yan, Q. Li, B. Goh, ‘China automakers pivot to hybrids for Europe to counter EV tariffs’, Reuters, 5 December 2024, reuters.com.

[32] ‘Commerce Finalizes Rule to Secure Connected Vehicle Supply Chains from Foreign Adversary Threats’, United States Department of Commerce, 14 January 2025, bis.gov.

[33] ‘China: Electric Vehicles. Question for Ministry of Defence’, Parliament of the United Kingdom, 6 March 2025, questions-statements.parliament.uk.

[34] T. Cotterill, ‘MoD tells staff not to discuss secrets in cars amid China spying fears’, The Telegraph, 18 November 2025, telegraph.co.uk.

[35] H. Sugars, ‘IDF recalls 700 Chinese EVs used by senior officers over security concerns’, The Jewish Chronicle, 4 November 2025, thejc.com.

[36] ‘China reacts to Poland’s plan to ban Chinese cars from military areas’, Polish Press Agency, 19 January 2026, pap.pl.

[37] ‘NÚKIB Warns Against the Transfer of the Data to and Remote Administration from People’s Republic of China’, National Cyber and Information Security Agency, 3 September 2025, nukib.gov.cz.

[38] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Industrial Action Plan for the European automotive sector, Council of the European Union, 5 March 2025, data.consilium.europa.eu.

[39] ‘Commission opens consultation on revising EU Cybersecurity Act’, European Commission, 11 April 2025, digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu.

[40] Regulation (EU) 2023/2854 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2023 on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data and amending Regulation (EU) 2017/2394 and Directive (EU) 2020/1828 (Data Act), Official Journal of the European Union, 22 December 2023, eur-lex.europa.eu.

[41] Regulation (EU) 2019/2144 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019, Official Journal of the European Union, 16 December 2019, eur-lex.europa.eu.

[42] ‘How to Secure the Connected & Automated Mobility (CAM) Ecosystem’, European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, 5 May 2021, enisa.europa.eu.

[43] UN Regulation No 155 – Uniform provisions concerning the approval of vehicles with regards to cybersecurity and cybersecurity management system [2021/387], Official Journal of the European Union, 9 March 2021, eur-lex.europa.eu.

[44] UN Regulation No 156 – Uniform provisions concerning the approval of vehicles with regards to software update and software updates management system [2021/388], Official Journal of the European Union, 9 March 2021, eur-lex.europa.eu.

[45] UN Regulation No 157 – Uniform provisions concerning the approval of vehicles with regards to Automated Lane Keeping Systems [2021/389], Official Journal of the European Union, 9 March 2021, eur-lex.europa.eu.

[46] Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation), Official Journal of the European Union, 4 May 2016, eur-lex.europa.eu.

[47] Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation), Official Journal of the European Union, 4 May 2016, eur-lex.europa.eu.

[48] B. Groothuis, C. Nagtegaal, ‘Security concerns around Chinese electric vehicles’, European Parliament, 26 September 2023; K. Złotowski, ‘Cybersecurity risks posed by Chinese technology’, European Parliament, 20 February 2024, europarl.europa.eu.

[49] W. Hazell, D. Penna, ‘China ‘will use electric cars to spy on Britain’’, The Telegraph, 5 August 2023, telegraph.co.uk.

[50] The Advance of Chinese technology, Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service, raport.valisluureamet.ee.