Excessive dependence? The growing role of US LNG and oil in the EU market

Since 2022, the EU has undergone a rapid transformation of its natural gas and crude oil import mix. Faced with Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine, now in its fourth year, and the Russian-European economic war, the EU has almost completely phased out imports of Russian oil and reduced its purchases of Russian gas to a minimum. Supplies from this source have largely been replaced by energy resources from the United States, whose share of the European market has increased markedly. This shift is most pronounced in US liquefied natural gas, which now accounts for nearly 30% of the EU’s total gas imports and 60% of its LNG imports, although levels of dependence vary significantly between individual countries. These shares are projected to increase in the coming years.

In some EU member states, this development has raised questions as to whether dependence on hydrocarbon imports from the United States, particularly LNG, could become excessive as supplies are expected to rise further, and whether such dependence might hinder diversification rather than support it. Concerns about overly close bilateral energy ties have been reinforced by a visible shift in US foreign, trade, and energy policies under President Donald Trump, as well as by certain US actions viewed by the EU as unfavourable, notably those relating to Greenland. Washington has further contributed to these concerns by casting doubt on at least some of the rules of international cooperation, the hierarchy of values, and the objectives it has previously shared with its allies.

The risk that the United States could weaponise energy supplies as political leverage is limited by fundamental differences between the EU’s dependence on gas imports from Russia and deliveries from the US. These include the global nature of the LNG market (as opposed to rigid pipeline connections), more flexible contracts, and the significantly more limited influence of political decision-makers on the operations of US companies.

EU imports of US LNG

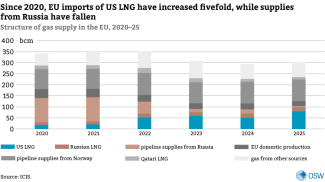

The EU’s growing energy dependence on the United States is most pronounced in the gas sector. Following the gas crisis and the outbreak of the full-scale war, the share of Russian gas in EU supply (domestic production plus imports) plunged from 36% in 2020 to 8% in 2025. Over the same period, purchases of US liquefied natural gas surged from 5% to more than 28% of the EU’s total LNG imports. The increase in US LNG deliveries between 2020 and 2025 accounted for almost two-thirds of the decline in Russian supplies to the EU over the same period.

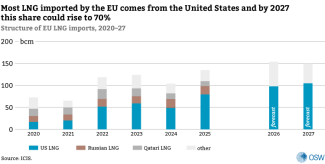

The share of US liquefied natural gas in the EU’s LNG import mix is even more significant. In 2025, it increased to almost 60% and is projected to rise further in the years ahead. According to an ICIS forecast, it could reach 70% as early as 2027. This stems from the EU’s plans to phase out Russian energy imports, a process expected to conclude within the next two years, and efforts to secure alternative LNG supplies, particularly through the signing of new contracts, mainly with US companies.[1] Another significant factor is that the key objectives of President Trump’s energy policy include expanding hydrocarbon production and exports, as well as encouraging higher imports of these fuels by countries in Europe and elsewhere.

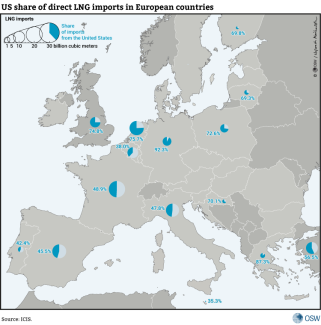

The dependence on US LNG varies greatly among individual European countries. In terms of direct deliveries, it is highest in Germany, where more than 90% of LNG imports come from the United States, and in seven other countries, including Poland and the UK, where this share exceeds 70%. However, the dependence of other countries, particularly Spain, France, and Belgium, may increase as they are expected to phase out imports of Russian LNG.

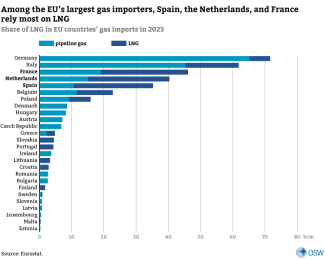

This picture is not complete. Actual dependence also reflects the role of LNG in the total gas imports of individual EU countries. For various reasons, most notably geographical location and access to the sea, some member states in practice rely almost exclusively on LNG, as is the case in Finland, Portugal, and Lithuania. Others, such as most Central European countries, import pipeline gas almost exclusively. However, this modus operandi tends to characterise relatively minor gas importers.

Most major European gas consumers import this fuel both via pipelines and in liquefied form. Among them, Spain and the Netherlands rely most heavily on LNG, which accounts for more than 60% of their total gas imports. Germany’s reliance on LNG is the lowest, at just 9% in 2023. According to Bruegel’s estimates, LNG accounted for more than 46% of the EU’s gas imports from third countries in 2025.[2]

Moreover, a number of EU countries purchase LNG from the United States (and from other sources) indirectly, which is not reflected in official statistics. They typically import it via the terminals and pipeline infrastructure of neighbouring countries. For example, the Czech Republic imports LNG through Dutch or German terminals, Austria relies on Italian and German infrastructure, while Germany itself sources substantial volumes via terminals in the Netherlands and Belgium.

US oil in the EU

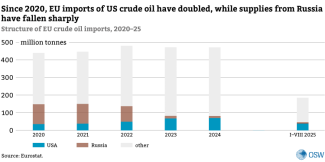

A similar pattern can be seen in oil, although the EU’s dependence on the United States for this fuel is significantly lower than in the case of US LNG. Since 2020, deliveries of crude oil from Russia have fallen tenfold, with its share of EU imports plunging from around 25% to 2.5%. Over the same period, purchases from the United States have doubled; US crude now accounts for about 15% of the EU market. Between 2020 and 2024, the increase in US supplies was equivalent to more than one third of the decline in Russian oil exports to the EU.

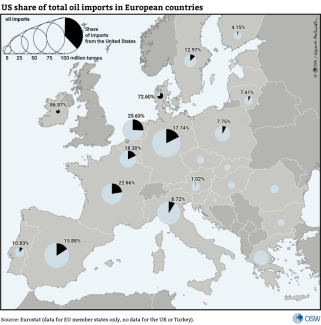

Similarly to LNG, US oil plays a varied role in individual European countries. Ireland and Denmark are the most dependent on it, but in most other member states its share of imports does not exceed the EU average of 15%. A number of EU countries, including those in Central and Southeastern Europe, do not purchase US crude at all.

The significance of the EU’s dependence on US gas and oil imports

The EU’s growing dependence on energy imports from the United States, particularly gas, has recently prompted increasing concern. This stems from a fundamental shift in Washington’s policy, emerging cracks in transatlantic unity and instances of the United States pursuing its own interests at the expense of those of its allies, for example with regard to Greenland. Repeated threats of sanctions, aimed at pressuring partners into taking actions favoured by the Trump administration, have raised questions about whether, and how, the United States could seek to exploit Europe’s dependence on US energy supplies for political purposes.

Concerns about this dependence on the United States may be reinforced by the fact that increasing hydrocarbon exports, including to the EU, is one of the priorities of the current US administration’s energy policy, as reflected in its pursuit of ‘energy dominance’.[3] An EU-US trade deal signed in July 2025 was intended to support this objective, with the EU political commitment to increase its imports of US energy, mainly gas and oil, to $250bn per year over the next three years. At the same time, advancing this goal could make it more challenging for Washington to use energy supplies as political leverage, since expanding these exports depends in part on the stability of supplies and credibility of US companies in meeting their contractual obligations.

Potentially the most critical factor is the dependence of the European Union and some of its member states, as well as the UK, on liquefied natural gas from the United States. Today, it already accounts for well over half of total LNG supplies to the EU. In the coming years, as EU countries plan to finalise the phase-out of Russian gas imports[4] and the scope for increasing pipeline supplies remains limited, the EU’s reliance on LNG will continue to grow.

A substantial portion of these additional LNG supplies is likely to come from the United States, driven by President Trump’s policy, import contracts signed by European and US companies, and the United States’ growing role in the global LNG market. The US is already the world’s largest exporter of LNG and its importance is set to increase further.[5] By 2030, almost 50% of new global liquefaction and export capacity coming online will be located in the United States.[6]

Amid the EU’s phase-out of imports from Russia, growing supplies from the United States are no longer contributing to efforts to diversify sources or increase the number of routes for supplying gas to the EU. At the same time, the nature of the bloc’s dependence on US LNG remains markedly different from the dependence European countries have experienced with regard to Russian gas. The state’s influence over the operations of energy companies in the United States is far smaller than in Russia. Any attempt by the Trump administration to use supplies to Europe for political purposes may also be constrained by the close ties between some administration officials and the US oil and gas sector. The risk is further reduced by the absence of clear alternatives to current volumes of US LNG deliveries to the European market. In the first ten months of 2025, 63% of total LNG exports from the United States went to EU countries and the UK.[7] A significant increase in supplies to the Chinese market and an expansion of US–China gas ties currently appear highly unlikely.

The nature of this dependence also differs due to the much greater flexibility of LNG trade, a trend that has continued in recent years. First, LNG is traded on a global market, and import terminals, unlike pipelines, allow buyers to source gas from a wide range of suppliers. Second, a growing share of contracts signed worldwide (around 45% in 2024 and expected to rise further), including those concluded by European buyers and often involving US companies, do not specify the cargo’s final destination.[8] This enables LNG to be delivered to virtually any location around the world, meaning that there is no permanent or unambiguous link between the country of origin and the market where it is ultimately consumed.

Moreover, the share of the portfolio players, including traders, in LNG trade has been rising in recent years, enhancing the liquidity and flexibility of the market. Finally, more than 300 bcm of new export capacity is expected to come online globally by 2030, with half of it located outside the United States, including in Qatar and Canada. This will significantly increase LNG availability and could lead to a global oversupply, heightened competition, and lower prices.[9] This oversupply would likely be compounded if Russia were to redirect larger volumes of gas to Asia, especially China.

None of this completely eliminates the risks associated with the EU’s already substantial and still growing dependence on supplies from the United States, or the potential for Washington to use them as political leverage. However, the logic of today’s global LNG market and the outlook for its development could mitigate these risks in the coming years. It is certainly legitimate to ask whether the United States will continue to abide by the rules that apply in the LNG and oil markets, or whether it will seek to undermine them in some way. For now, it appears to be fully leveraging the opportunities offered by the global markets to pursue its energy policy objectives and stimulate exports. It has recently deployed political instruments to bolster its influence over these markets, notably by seeking to gain control over parts of its competitors’ sales outlets, as demonstrated by its actions in Venezuela and its reported interest in Russia’s gas export pipelines. However, it does not appear to be seeking to overturn the rules of the game.

Any steps to reduce the EU’s dependence on imports of US LNG would undoubtedly face significant political challenges in the near term. However, a global oversupply and the current rules of the game on the international LNG market could create more favourable conditions for such moves. Given the EU’s ongoing decarbonisation process and the prospect of a substantial long-term decline in natural gas consumption in Europe, European companies may seek to conclude LNG purchase contracts on the most flexible terms possible, and without a specified final destination. This would allow them to adjust delivery volumes and routes to the EU’s actual needs, which have recently become highly unpredictable. With European demand expected to decline over time, such flexibility would also help them to remain profitable by enabling them to generate revenues from trade, including in US gas, with countries where demand remains stronger.

[1] In November 2025 alone, the US company Venture Global signed long-term contracts for LNG sales with the Greek firm Atlantic-See LNG and Spain’s Naturgy, see: ‘Venture Global. Press Releases’, investors.ventureglobal.com.

[2] See: Bruegel Dataset: U. Keliauskaitė, B. McWilliams, G. Sgaravatti, G. Zachmann, ‘European natural gas imports’, version as of 22 January 2026, Bruegel, bruegel.org.

[3] See: ‘Energy Dominance’, The White House, whitehouse.gov.

[4] A. Łoskot-Strachota, ‘End of Russian gas imports to the EU: closer than ever’, OSW, 16 January 2026, osw.waw.pl.

[5] See: 2025 World LNG Report, International Gas Union, at: datocms-assets.com.

[6] See: ‘Cumulative LNG liquefaction capacity additions from post-FID projects’, International Energy Agency, 22 October 2025, iea.org.

[7] Calculations based on ‘U.S. Natural Gas Exports and Re-Exports by Country’, U.S. Energy Information Administration, eia.gov.

[8] See: Gas 2025. Analysis and forecasts to 2030, International Energy Agency, October 2025, iea.org.

[9] Ibid.