An uncertain future for Rosatom’s nuclear technology exports

Despite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Rosatom, unlike many other Russian energy companies, has not faced significant Western sanctions. This has enabled it to continue operating in the key area of supplying nuclear technology to foreign countries; this applies in particular to the construction of nuclear reactors. Against this backdrop, the corporation has been steadily working to shield its operations from further Western pressure. This is seen both in its focus on projects in non-Western countries and in its efforts to extend its cooperation with local partners.

Although work has continued on most of Rosatom’s international projects, the corporation’s prospects for expanding its role as a nuclear technology supplier into the 2030s remain uncertain. This is especially true in light of intensifying competition in the field of next-generation reactors, where Russian companies will face stiff competition from their Chinese rivals. Rosatom’s performance may also be affected by the economic situation in Russia. Should conditions deteriorate, the government is likely to become less willing to finance overseas investments. Under this scenario, the attractiveness of the Russian offer would diminish significantly.

Rosatom’s role as a technology supplier

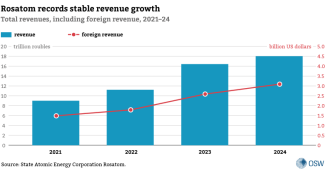

Unlike much of Russia’s energy sector – including the coal, gas and oil industries – the State Atomic Energy Corporation Rosatom has recorded steady revenue growth since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. According to the company’s financial reports published between 2022 and 2024, it succeeded in increasing both its foreign revenue and total revenue.

According to the 2024 report, this revenue growth was driven in part by the implementation of contracts for constructing reactors abroad – a core area of Rosatom’s operations. For years, this activity has served as one of the key instruments for advancing Moscow’s ambitions in the nuclear domain.[1] Strengthening Russia’s position in the construction and modernisation of nuclear facilities is intended to yield both economic and political benefits. By building reactors in foreign markets, Rosatom generates profits from recipient states as they repay their obligations for the services provided and the technology supplied. These investments are often accompanied by long-term contracts for the supply of Russian-produced nuclear fuel or for support in operating the facilities.

From a political standpoint, this form of cooperation fosters long-term ties between third countries and Russia in the area of energy security, although the depth of these relationships depends on the type of contract and other elements of the offer, including financing arrangements and the ownership structure of the plant. In this context, projects that create multi-year dependencies, for example through loan repayment obligations or the ownership structure of the special purpose vehicle, are particularly significant. Under the build-own-operate model promoted by Rosatom, the reactor effectively remains Russian property and thus beyond the control of the domestic government.

Rosatom boasts of its dominance in the global market for nuclear technology exports, claiming to account for nearly 90% of investments in this sector.[2] In reality, though, by the end of 2025, the corporation had signed agreements to build 22 reactors in seven countries, while around 60 to 70 of these facilities are currently under construction worldwide. Rosatom’s projects vary in terms of its level of involvement, financing models and stages of advancement. The company is building nuclear facilities primarily in Asia (Turkey, Iran, China, Bangladesh and India), alongside developments in Hungary and Egypt. However, in all these cases, construction began before 2022. Three new projects announced over the past three years, in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Iran, have yet to be formalised.

Table. Nuclear reactors currently under construction by Rosatom abroad

Russian ‘turnkey’ reactors

Rosatom’s strong position as a nuclear technology supplier stems primarily from its corporate structure and the financial support it receives from the state. For a prospective client seeking to build a nuclear power plant, the corporation functions as a comprehensive, one-stop shop. Its affiliated companies offer services covering the entire value chain of the civil nuclear industry – from design and construction to the training of technical staff and ongoing operational support, including the supply of fuel. Moreover, its offer may be underpinned by financing for a significant stretch, or even the entirety, of the investment in the form of low-interest loans provided by Russian entities, often on the basis of an intergovernmental agreement.

Owing to these two factors, Rosatom is seen as an attractive bidder on the international market. Potential competitors, primarily from Western countries, are unable to offer a similarly comprehensive package within a single organisational structure. This forces them to assemble large consortia, a process that complicates and prolongs the implementation of their projects. The ability to cover the full cost of construction clearly sets Rosatom apart from Western companies, which typically require co-financing from the host country. This is a major advantage of the Russian offer, particularly from the perspective of countries which do not have the sufficient funds for such capital-intensive investments. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that this model places a substantial burden on Russia, as it entails the allocation of large amounts of funding without any guarantee of a positive return. Loans are often granted at low interest rates, with the Russian state providing most of the capital.

Crucially, Rosatom’s leading role – not only as an exporter of nuclear technology, but also as a supplier of nuclear fuel and a dominant player in the global uranium enrichment market – has shielded the corporation and its affiliated companies from EU sanctions imposed since 2022. Although the West has declared its intention to reduce its dependence on Rosatom and has already taken concrete steps towards this end (for example, by securing alternative fuel suppliers), Rosatom continues to cooperate with selected Western companies. In 2024, Rosatom subsidiaries accounted for around 15% of enriched uranium deliveries to the EU. Their exports also covered 20% of US demand for enriched uranium[3] – a share that increased again in 2025.[4]

Moreover, the Kremlin has refrained from leveraging Rosatom for political purposes, for example by ordering it to halt fuel exports or suspend services provided to Western companies as a form of energy blackmail. This stands in contrast to its instrumentalisation of Gazprom, which deliberately reduced gas supplies to Europe starting in 2021.[5] It is worth noting, however, that on the rhetorical level, the Russian government has entertained this possibility.[6] In response to US restrictions on the import of enriched uranium from Russia, the Kremlin imposed limits on the export of this material to the United States,[7] though in practice, this measure remains a dead letter.[8] Rosatom’s relative operational freedom has enabled it to consolidate its reputation as a reliable partner, seemingly excluded from Moscow’s political calculations.

Sanctions fallout: Finland, Turkey and Hungary

Despite its privileged position in the global market, Rosatom has encountered difficulties in constructing nuclear power plants since 2022. In the new international landscape that emerged following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the corporation lost one of its key projects. In May 2022, construction of a reactor unit on Finland’s Hanhikivi peninsula, led by Rosatom’s subsidiary Atomstroyexport, was abandoned when its local partner, Fennovoima, terminated the contract, citing delays caused by the Russian side and heightened risks related to supply chain disruptions following the outbreak of the full-scale war.

At this stage, Rosatom is also facing obstacles in the implementation of two other projects that began before 2022: Hungary’s Paks II and Turkey’s Akkuyu. In the case of the former, construction of two VVER-1200 reactor units is more than a decade behind schedule,[9] a delay exacerbated by difficulties encountered over the past three years. In 2022, the corporation was forced to renegotiate existing contracts in order to enable its subsidiaries to continue operating and receive financing under the constraints of Western financial sanctions. Moreover, political pressure in Germany led to delays in the delivery of Siemens turbines destined for the plant. It is also worth noting that, although the Trump administration exempted Paks II from earlier US sanctions,[10] in September 2025, the Court of Justice of the EU issued a ruling that annulled the European Commission’s approval of state aid for the project, causing further delays[11] at a time when concrete is yet to be poured for the first unit.

Akkuyu, where Rosatom has been constructing four VVER-1200 reactors, is a far more advanced project. As in the case of Hungary’s Paks II, it has faced challenges related to financing and the supply of Western components. As a result, the commissioning of the first unit was postponed from 2023 to 2026. Both sides have been working continuously to overcome these difficulties. For example, they have developed a mechanism that allows the costs of the reactor units to be covered by transferring payments for Russian gas directly into the account of a special purpose vehicle in Turkey.[12]

From Rosatom’s perspective, the success of the Turkish project is particularly important due to its unique nature: it is the first investment being developed under the build-own-operate (BOO) model, which grants Rosatom full control over the construction process and allows it to retain ownership of the facility throughout its operational lifespan. The corporation exercises complete control over the local special purpose vehicle; any potential sale of shares in Akkuyu remains at Russia’s discretion. In practice, this limits Turkey’s influence over the progress of the project – a fact clearly underscored by Rosatom’s decision to terminate its contract with a local construction subcontractor, replacing it with a Russian company. The BOO model, championed by Sergei Kiriyenko (then head of the corporation) as early as the previous decade,[13] is intended to become the default export offer for countries interested in Russian nuclear technology. This lends particular importance to the pioneering project in Turkey.

Uninterrupted progress: Egypt, Bangladesh and Iran

As the main contractor operating under EPC (engineering, procurement and construction) agreements, Rosatom has also been implementing three other projects, located in Egypt (El Dabaa), Bangladesh (Rooppur) and Iran (Bushehr). These investments were already at an advanced stage prior to 2022, which increases the likelihood they will be completed. However, they have also encountered sanctions-related difficulties, particularly in relation to payments and supply logistics.

Implementing projects in countries that are less integrated with Western markets than Hungary and Turkey gives Rosatom greater leeway in navigating sanctions-related obstacles, as illustrated by the case of the Rooppur plant in Bangladesh. Nonetheless, even this project faced logistical difficulties in 2023, when Western countries imposed restrictions on Russian vessels, forcing the corporation to reorganise its supply chain for the site. The same year, faced with sanctions targeting Russian banks, the parties agreed to change the method of repaying the loan which Russia had provided for the construction of the units: the debt will be settled in Chinese yuan through China’s CIPS payment system, effectively insulating the transactions from Western-controlled capital flows.[14]

In the case of the other two projects, located in Egypt and Iran, sanctions have been described as an unspecified obstacle that has not hampered progress. According to the Russian ambassador to Egypt, they have only affected the Egyptian investment “to some extent”.[15] In late 2024, Rosatom insisted that sanctions had not had “any substantial impact” on this project.[16] As for the Iranian context, delays in constructing the facility in Bushehr stem from earlier problems, notably Iran’s failure to repay outstanding debt.[17]

High local involvement: India and China

The projects implemented with a high level of involvement from local contractors – namely, the nuclear units at Kudankulam in India and at Tianwan and Xudabao in China – have been least affected by sanctions. In these cases, Rosatom does not act as the main contractor but shares construction responsibilities with domestic companies. In the Chinese projects, the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) has assumed full responsibility for construction, except for the ‘reactor island’ – the ‘heart’ of the power plant housing the reactor. Rosatom’s tasks include building that core part of the facility and providing comprehensive oversight of its construction and commissioning. Importantly, China will produce fuel for the units under a Russian licence.

In the past, Rosatom reported[18] that for Chinese reactors built a decade ago, the so-called localisation rate – that is, the level of involvement from local companies – stood at around 75%. It can be assumed that the role of domestic entities has only increased since then, making it increasingly difficult to categorise these projects as ‘Russian’. By contrast, at India’s Kudankulam plant, Rosatom is responsible for supplying the technology and carrying out the majority of construction work. For the reactors currently under construction, the localisation rate is expected to reach 50%.[19] It should be noted that these percentage figures typically refer to the entire construction process, without distinguishing between the relative importance of individual components – for example, between the ‘reactor island’ and standard construction work.

Crucially, local entities exercise full control over the facilities, both during construction and throughout their operational lifespan. However, these projects differ in terms of financing: while China has funded its reactors entirely with its own resources, in India Russia has covered part of the cost of the units. It is worth noting that Russia’s capital contribution has been gradually decreasing as the Indian site expands. For the first four reactors at Kudankulam, Russia made a commitment to finance approximately 85% of the work, whereas for the two subsequent units, it is providing a loan covering around 50% of their value.

At the preliminary stage: Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Iran

Rosatom has continued its lobbying efforts, seeking to secure agreements for the construction of new nuclear units. The most concrete projects to date are those in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Iran. However, none of them has entered the active implementation phase, raising doubts about their short-term viability.

The most advanced of these projects is located in Uzbekistan’s central-eastern Jizzakh region. Preparatory work began there in October 2025.[20] According to arrangements made last year, Rosatom will build a ‘hybrid’ nuclear power plant consisting of two large VVER-1000 reactors and two SMRs – small modular reactors of the RITM-200N type, though initial plans had envisaged only the latter.[21] A detailed contract formalising the project is scheduled to be signed in March 2026.[22] Notably, this will most likely represent the first overseas deployment of Russian SMR technology.

The project in Kazakhstan is at an earlier stage of development. In June 2025, Rosatom was selected as the ‘leader of an international consortium’[23] tasked with building the country’s first nuclear power plant, to be named Balkhash.[24] Geological preparatory work is currently underway at the designated site[25] and the parties are discussing the technical and financial parameters that will form the basis of the contractual terms. The facility is expected to consist of two VVER-1200 units. It remains unclear how Rosatom will collaborate with the other members of the ‘consortium’ in the construction of the plant.

In 2025, reports also emerged about Iran’s interest in new nuclear facilities that the Russian corporation could build in addition to the ongoing project in the city of Bushehr. In September, the two countries signed a memorandum on cooperation in the field of constructing SMRs;[26] in October, Russia’s ambassador to Iran announced that talks were underway regarding a potential site for a ‘large’ nuclear unit named Hormoz.[27] In November, the Iranian media reported another intergovernmental agreement, envisaging the construction of eight reactors (excluding the four units in Bushehr), which implies the development of a new site.[28] The Russian side has not confirmed these reports, which essentially represent a modification of plans first announced a decade ago,[29] nor has it provided any contractual details.

Conclusions: the challenge of maintaining market dominance in the 2030s

The fact that work is ongoing on most of Rosatom’s foreign ventures, with the exception of the cancelled Hanhikivi-1 project in Finland, indicates that the corporation has largely succeeded in navigating sanctions-related obstacles since 2022. However, the political will of the host countries remains the key condition for continuing the construction of nuclear power plants, as illustrated by the projects in Turkey and Hungary. The decision not to impose effective sanctions on the corporation, which equates to it being deliberately excluded from the broader sanctions regime, has enabled the interested countries to maintain largely unfettered cooperation with it. The difficulties stemming from other restrictions imposed on Russia, particularly in the areas of logistics and financial settlements, have so far caused only temporary delays in implementing projects.

By continuing work on its projects, Rosatom has managed to reinforce its image as a ‘reliable’ contractor and to maintain the appearance of independence from the Kremlin’s political agenda. However, it is important to note that the company now appears to be effectively excluded from any future involvement in new projects on Western markets. This stems not only from pressure being exerted on Russia through sanctions, but also from the company’s role in the defence sector and its unlawful takeover of Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant.

Nevertheless, Rosatom’s positive reputation among its existing clients is underscored by its flexibility in accommodating partners – whether by renegotiating financing arrangements, as in the case of Bangladesh, or by stepping in to replace Western partners, as seen in Turkey. However, sanctions have led to project delays and forced the corporation to undertake costly adaptations, requiring it to seek alternative solutions following the loss of certain clients for its services.

Sanctions-related constraints have reinforced the need to insulate Rosatom’s operations from Western political pressure. This suggests that the corporation will increasingly seek collaborators from non-Western countries in future consortia. Ongoing talks with prospective new partners are still far from producing concrete arrangements regarding either the investment timelines or Rosatom’s precise role. It is, however, worth noting that the geographical scope of these projects indicates a clear focus on countries where Russia wields significant political influence.

Rosatom’s ongoing projects are based on agreements signed a decade ago and the corporation has not concluded a single binding contract for a new venture over the past five years. This could result in a significant slowdown in its activity during the 2030s, once the current projects are completed. Over time, the company’s competitive advantages may also diminish, particularly if it fails to develop attractive offers beyond its traditional portfolio, namely the Generation III+ reactors it is currently building. Moreover, given the growing global interest in SMRs, Rosatom is likely to face stiff competition in this segment from players such as China, which has been actively developing SMR technology with a view to exporting it. Therefore, the appeal of Russia’s offer in this area will depend in part on the success of its project in Uzbekistan. The company’s prospects are further clouded by efforts to ‘derussify’ the nuclear technology market, being driven primarily by Western countries.

It should be noted that capturing new markets, particularly in non-Western countries which express an interest in Russian reactors, may also require offering attractive financing. Should Russia’s economic situation deteriorate further, the state will find it increasingly difficult to provide favourable loans for Rosatom’s projects. This would undermine the viability of its build-own-operate model, which is currently only being implemented in Turkey. An inability to provide substantial co-financing may also diminish Rosatom’s role as a political instrument for expanding Russia’s influence abroad.

[1] M. Menkiszak, Aktywność zagraniczna Rosji w sferze energii nuklearnej, OSW, Warszawa 2011, osw.waw.pl.

[2] ‘“We Aim for Long-Term Cooperation”’, Rosatom Newsletter, February 2025, rosatomnewsletter.com.

[3] A. Natter, ‘Russia Still Top Supplier of US Nuclear Fuel Despite Import Ban’, Bloomberg, 30 September 2025, bloomberg.com.

[4] D. Gorchakov, ‘EU and US reduce Russian uranium and nuclear fuel purchases in 2024’, Bellona, 13 January 2025, bellona.org; F. Rudnik, ‘Russia continues to export uranium to the United States’, OSW, 18 June 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[5] F. Rudnik, ‘Farewell to Europe: Gazprom after 2024’, OSW Commentary, no. 644, 11 February 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[6] ‘Новак прокомментировал возможность запрета на экспорт урана из России’, TACC, 21 March 2022, tass.ru.

[7] И. Шульгина, ‘Россия временно ограничила экспорт обогащенного урана в США’, Ведомости, 15 November 2024, vedomosti.ru.

[8] See: F. Rudnik, ‘Russia continues to export uranium to the United States’, op. cit.

[9] I. Gizińska, A. Sadecki, ‘Russia’s nuclear project in Hungary: France’s growing role’, OSW Commentary, no. 520, 4 July 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[10] I. Gizińska, F. Rudnik, ‘Hungarian-Russian Paks nuclear project: a new breach in Western sanctions’, OSW, 14 July 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[11] I. Gizińska, ‘Dark clouds over Paks II: no approval for Hungary’s state aid’, OSW, 17 September 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[12] A. Michalski, F. Rudnik, ‘Turkey’s nuclear power plant: old problems, new solutions’, OSW, 3 September 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[13] C. Digges, ‘Putin leaves Kazakhstan without deal to build nuclear plant’, Bellona, 5 December 2024, bellona.org.

[14] A. Kashem, ‘Russia extends Rooppur loan repayment by two years, waives $164m penalty’, TBS News, 16 April 2025, tbsnews.net.

[15] ‘Russian ambassador to Egypt assessed the impact of sanctions on the El Dabaa NPP project’, Известия, 5 February 2025, en.iz.ru.

[16] ‘Rosatom Newsletter, nr 11 (283)’, November 2024, rosatomnewsletter.com.

[17] ‘Россия и Иран решили вопросы по долгу перед Росатомом по строительству АЭС "Бушер"’, TACC, 17 May 2023, tass.ru.

[18] Росатом: Итоги деятельности 2014, Rosatom, report.rosatom.ru.

[19] ‘Russia eyes over 50% localisation for new Kudankulam reactors’, The Indian Express, 12 November 2017, indianexpress.com.

[20] ‘В Узбекистане стартовал первый этап строительства АЭС. Когда начнут запускать энергоблоки?’, Gazeta, 13 October 2025, gazeta.uz.

[21] ‘"Узатом" и "Росатом" договорились о конфигурации АЭС в Узбекистане и поставках ядерного топлива’, Интерфакс, 26 September 2025, interfax.ru.

[22] ‘Узбекистан и Россия готовят контракт на строительство крупной АЭС с двумя энергоблоками ВВЭР-1000’, Атомная энергия, 13 October 2025, atomic-energy.ru.

[23] Д. Искакова, ‘Росатом выбран лидером международного консорциума по строительству первой АЭС в Казахстане’, Казинформ, 14 June 2025, inform.kz.

[24] D. Dalton, ‘Kazakhstan Announces Name Of First Nuclear Power Station’, NucNet, 17 November 2025, nucnet.org.

[25] S. Sakenova, ‘Kazakhstan Launches Preliminary Works at First Nuclear Power Plant’, The Astana Times, 8 August 2025, astanatimes.com.

[26] ‘РФ и Иран подписали меморандум о сотрудничестве в строительстве малых АЭС на территории Ирана’, Интерфакс, 24 September 2025, interfax.ru.

[27] ‘Иран и Россия работают над проектом АЭС большой мощности’, TACC, 28 October 2025, tass.ru.

[28] ‘Iran to Build 8 New Nuclear Plants with Russia’s Help’, Tasnim News Agency, 2 November 2025, tasnimnews.com.

[29] ‘ROSATOM to Build Eight New Reactors in Iran’, Rosatom Newsletter, November 2014, rosatomnewsletter.com.