The CDU/CSU–SPD government facing economic challenges

According to the government forecast, the German economy will remain stagnant in 2025, marking the third consecutive year without GDP growth. The CDU/CSU–SPD coalition faces the urgent task of implementing comprehensive reforms aimed at improving conditions for doing business and stimulating domestic demand. Planned measures include reducing bureaucracy, relaxing the so-called debt brake, establishing a special investment fund, and introducing tax relief for companies. The absence of an approved budget for the current year poses a major challenge for the government. This stems from the coalition’s collapse and a snap election, and restricts the government’s ability to initiate new investment projects.

The condition of the country’s economy will be influenced not only by internal factors. External actors – namely the United States, China, and the European Commission – also play a significant role, as Germany’s trade policy largely depends on them. Currently, the European Union faces the threat of 50% tariffs from Washington. The European Commission is expected to have concluded a trade agreement with the United States by 9 July. Failure to resolve this issue could seriously harm the German economy and render Berlin’s reform efforts inadequate, given the country’s strong dependence on foreign markets.

Problems faced by the German economy

The main causes of the German economy’s woes include, above all, the prevailing uncertainty in international trade and Germany’s structural problems, such as an unfavourable demographic structure, excessive bureaucracy, a low level of business innovation, and high energy prices.

Key economic challenges for Germany include an ageing population and a shortage of skilled workers. Labour shortages are particularly evident in sectors linked to industrial transformation, such as electromobility, green technologies, and digitisation. Among the federal states, Bavaria – Germany’s third most industrialised region – faces the most acute situation, with the available workforce able to fill only 48% of vacancies. The labour shortage in Germany is expected to worsen across all sectors, with estimates suggesting that approximately 3.5 million individuals may leave the workforce within the next 10 years. Even assuming that annual immigration reaches 460,000 individuals (while current projections estimate it at around 330,000), the working-age population is projected to decline by approximately 1.5 million by 2035. The settlement of migrants in Germany is hindered by excessive bureaucracy and a low level of digitisation in administrative services. This significantly prolongs procedures such as the recognition of professional qualifications and the issuance of visas and work permits.

The Munich-based Ifo Institute estimates that private-sector companies in Germany incur annual costs of €146 billion due to reporting obligations. Businesses have long pointed out that excessive bureaucracy is one of the most significant barriers to running a business effectively. It also deters foreign investors. Consequently, the competitiveness of German companies is declining, with domestic businesses proving insufficiently innovative compared with their international counterparts. This is particularly evident in sectors such as artificial intelligence, microelectronics, and electromobility, where sales are dominated by Chinese brands (BYD, Geely, Chery, etc.) and the American company Tesla.

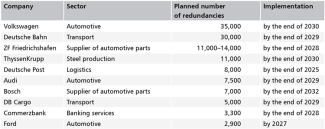

The decline in the attractiveness of German-made products is leading to a growing number of business closures, particularly in the manufacturing sector. The scale of this phenomenon is comparable to the situation during the 2008 financial crisis. Investment is also declining – according to the German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA), 76% of automotive suppliers intend to postpone their planned projects in Germany, relocate them abroad, or cancel them altogether. Consequently, production is being scaled back, and large-scale redundancy programmes are being implemented (see Table 1). However, labour shortages continue to significantly exceed the number of available workers, as the skills of those losing their jobs do not sufficiently match the requirements of emerging technological sectors.

High energy prices have posed another significant problem for the German economy in recent times. Although Germany has never enjoyed low electricity or natural gas costs (Eurostat figures indicate that energy prices have exceeded the EU average for many years), companies operating there were previously able to compensate for this with other competitive advantages. However, due to the sharp rise in energy prices since 2021 (electricity prices increased by several dozen percent and gas prices by over 100%) many products, especially from energy-intensive industrial sectors, have lost their competitiveness on global markets. A prime example of this is Germany’s key chemical sector, in which natural gas is both a basic raw material and an energy carrier. A comparison of German energy prices with those in countries such as the United States and China is particularly unfavourable for Germany. In those countries, energy costs are up to three times lower, and local businesses are among the main global competitors of German enterprises.

In addition to domestic factors, external actors also have a tangible impact on the German economy. The country’s prosperity has, for decades, relied on export-driven trade surpluses (in 2024, foreign sales accounted for 41.8% of Germany’s GDP). The United States is Germany’s most important trading partner and largest export market, with a trade surplus of €70.3 billion. However, the unpredictable protectionist actions of Donald Trump could result in a significant decline in trade with the US in the coming years. These developments also generate additional uncertainty for German companies, making it more difficult for them to plan their business strategies.

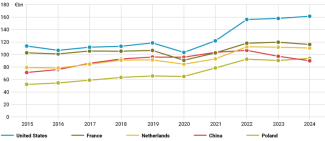

China is Germany’s second most significant trading partner, although in recent years it has declined in importance as a destination for German exports (see Chart). Goods imported from Germany are increasingly being replaced by cheaper Chinese products, which frequently offer higher quality. Moreover, the People’s Republic of China is becoming an increasingly challenging environment for foreign companies due to unfair practices by the Chinese government.[1] In 2025, total German exports are expected to decrease by 2.8%, with only a modest rebound forecast for 2026, at 0.7%.

Barriers to reforms

The new government has identified overcoming economic stagnation as one of its priorities. The CDU/CSU–SPD coalition has presented a comprehensive programme of economic reforms,[2] aimed at revitalising both private and public investment. However, the implementation of these plans is hindered by the fact that Germany is still operating under a provisional budget, which only permits the financing of expenditures essential to the functioning of the state. As a result, new initiatives remain delayed. To address this issue, on 28 May, during an informal meeting of the coalition committee, its members agreed to implement numerous measures outlined in the coalition agreement, with some due to be introduced before the summer recess. These include the creation of a special €500 billion fund for infrastructure investment over a 12-year period, reform of the debt brake,[3] financial support for small businesses and start-ups, and the introduction of tax incentives (including for businesses, scientific research, and the purchase of electric vehicles).

Finance Minister Lars Klingbeil (SPD) refers to himself as the ‘investment minister’ and intends to counteract economic difficulties through an expansive fiscal policy. However, the government’s ambitious plans may be disrupted primarily by the strained budgetary situation. Revenues in 2025 are expected to amount to €979.7 billion, which is €19.1 billion less than forecast last autumn. Over the period from 2025 to 2029, revenues are projected to fall short by a total of €81.2 billion. The tax reliefs for businesses proposed in the government’s draft bill will further reduce budget revenues beyond what was previously accounted for: €630 million in 2025 and €17 billion by 2029. This necessitates cost-cutting, prompting Klingbeil to revise his earlier narrative and announce spending reductions across all ministries. The federal government’s fiscal policy is drawing criticism from federal states and municipalities, which have for years been burdened by increasing financial demands imposed by Berlin. These demands are not offset by additional revenues, leading to substantial disapproval of the government’s tax relief plans, such as the proposed reduction of VAT on restaurant and catering services.

Another obstacle to implementing reforms is the questionable feasibility of utilising the resources from the aforementioned infrastructure fund. This is hindered by EU regulations stemming from the Stability and Growth Pact: accessing these funds could raise Germany’s public debt from the current 62.5% to 90% of GDP. Consequently, Berlin will seek changes to these rules. The first step in this direction was already taken by Klingbeil’s predecessor, Jörg Kukies (SPD). However, sweeping reforms appear unlikely due to resistance from other EU member states, particularly those most heavily indebted. On the one hand, they advocate the mutualisation of public debt through the issuance of Eurobonds; on the other hand, they are reluctant to support a sudden policy reversal by Germany, which under previous governments consistently pushed for stricter fiscal rules for EU countries facing financial hardship.

Outlook

An expert report published in May by the government advisory body (Sachverständigenrat) indicated that Germany’s GDP is expected to grow by 1.0% in 2026. This growth will largely depend on the effective utilisation of funds from the aforementioned special fund. It is crucial that these resources are allocated to additional investments, rather than merely reallocated from the general budget to finance election pledges that do not contribute to economic growth, such as increasing the commuter tax allowance or reducing VAT on catering services. Economists argue that the volume of transfers from the infrastructure fund could reach up to €50 billion annually, which they believe should be subject to a legal cap. At the same time, inflation and unemployment levels are projected to decline slightly in the coming year (see Table 2).

The precise course of action that the government should take remains a point of contention among experts. Critics of the special fund argue that creating additional resources for investment is not only unnecessary but also poses a threat to the stability of Germany’s public finances, owing to the projected increase in debt. Instead, they advocate substantial deregulation rather than merely improving the enforcement of existing rules. This free-market approach aims to stimulate the private sector by introducing clear and simplified regulations. Its proponents attribute the current economic challenges to excessive state intervention in the economy.

The issue of economic revival will serve as a political test for the CDU/CSU–SPD government, particularly amid growing social radicalisation linked to prolonged stagnation. The rising popularity of the AfD increases pressure on the ruling coalition and compels it to take swift action. In 2026, state elections will be held in Berlin, Rhineland-Palatinate, Baden-Württemberg, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, and Saxony-Anhalt. In the latter two regions, support for the AfD stands at around 30%, further intensifying political tension. Time is not on the coalition’s side: investments will yield results only in the medium and long term, so the earlier the announced reforms are implemented, the greater the chance that their initial effects will be visible as early as next year.

Table 1. Examples of German companies planning layoffs

Source: Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der gesamtwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung, Frühjahrsgutachten 2025.

Table 2. Germany’s selected economic indicators

Source: Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der gesamtwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung, Frühjahrsgutachten 2025.

Chart. The value of Germany’s exports to selected countries in current prices

Source: German Federal Statistical Office.

[1] A. Kozaczyńska, ‘German exports under pressure. Germany’s trade in 2024’, OSW, 4 March 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[2] OSW’s Department for Germany and Northern Europe, ‘Course adjustment: the CDU/CSU–SPD coalition agreement’, OSW Commentary, no. 660, 17 April 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[3] Idem, ‘Agency on credit: Germany releases the debt brake’, OSW Commentary, no. 657, 11 April 2025, osw.waw.pl.