The year of Péter Magyar: great expectations, great challenges

One year ahead of Hungary’s parliamentary elections, Viktor Orbán, who has been in power for 15 years, faces a formidable challenger. Péter Magyar, a previously little-known Fidesz activist, began to play a major role in Hungarian politics in the spring of 2024. He capitalised on the largest scandal to hit the ruling party in years – a pardon granted by President Katalin Novák to a person convicted of covering up child abuse – using it to expose misconduct within the ruling elite and to highlight state dysfunction while pledging to bring an end to Orbán’s rule. Since then, he has established himself as the opposition’s new leader, transforming a social movement into a political party called TISZA. Under his leadership, the party has secured representation in the European Parliament and Budapest’s local government; it has also overtaken the ruling Fidesz in independent opinion polls.

Although much could still change in the run-up to the parliamentary elections, public enthusiasm generated by Magyar’s initial successes has positioned him as the only credible challenger to Orbán. Hopes for a change in power have been fuelled by the ruling camp’s reputational crisis and the waning appeal of its narrative, which remains focused on an ideological struggle against the ‘liberal West’, as well as economic hardships that are increasingly affecting the population. However, the prospect of a political shift in Hungary is tempered by the fact that after more than a decade of majority rule, Fidesz has consolidated power to such an extent that it is now impossible for the opposition leader to compete on equal terms.

Orbán’s challenger makes his debut

Within the span of just a year, Péter Magyar has emerged from relative obscurity as a background figure in Fidesz to become the leader of the opposition and Viktor Orbán’s principal political rival. He gained national prominence in February 2024, when a political scandal erupted over the pardon of a deputy director of a children’s home who had been convicted of covering up abuses against minors. The fallout led to the resignation of President Katalin Novák and the withdrawal of Justice Minister Judit Varga, Magyar’s former wife, from political life after she had co-signed the pardon.[1]

On 10 February, the day of the president’s resignation, Magyar published a Facebook post that quickly gained widespread attention. He argued that Orbán had unjustly shifted the political consequences of the pardon onto the two women involved, thus publicly distancing himself from the ruling camp. He resigned from his positions in state-owned companies and gave several high-profile interviews in which, speaking as an insider, he exposed irregularities within the ruling elite. He subsequently announced the creation of a movement called ‘Rise Up, Hungarians’ – a name that references the slogan of Hungary’s 1848 Spring of Nations revolution. The movement staged large-scale anti-government demonstrations in Budapest on 15 March and 6 April, drawing crowds not seen in years, with tens of thousands taking to the streets.

As there was insufficient time to register his movement as a political party ahead of the European Parliament elections, Magyar decided to run under the banner of TISZA – a little-known party at the time. It has a centre-right profile, but Magyar, its chairman since July 2024, has avoided clear ideological positioning in an effort to appeal to the broadest possible electorate. He has presented the party primarily as a political force committed to removing Fidesz from power. In the June 2024 European Parliament elections, TISZA came second with 29.7% of the vote, securing seven seats. Despite his earlier statements that he had no intention of becoming an MEP, Magyar ultimately accepted the mandate, and TISZA joined the European People’s Party (EPP) in the European Parliament.

Magyar’s arrival on the national political stage has reshaped the dynamics of Hungarian politics. Despite initial scepticism among opposition supporters, for whom his Fidesz background was potentially problematic, Magyar has, within a year, emerged as the undisputed leader of the anti-Orbán camp. He has sought to turn his former party affiliation into an asset, arguing that, as someone with ‘insider knowledge’, he understands the inner workings of the system and knows how to dismantle it. One of his main pledges is to hold the ruling elite accountable – even though he was once part of it. The controversies surrounding him – many of which have been amplified or even generated by the ruling party, including allegations of domestic abuse made by his former wife, ex-minister Judit Varga; video recordings of morally questionable behaviour in public spaces; and leaked conversations in which he insults participants in his own rallies and TISZA’s MEPs – have thus far failed to dent his popularity. Magyar has so far proven to be a ‘Teflon politician’ to whom no scandal seems to stick.

Upheaval in Hungary’s party landscape

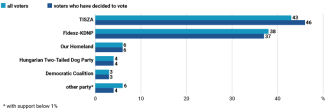

In October 2024, for the first time in 18 years, Hungary’s governing Fidesz-KDNP coalition was overtaken in the polls by another party. The most recent survey by the Medián Institute – widely regarded as the country’s most credible polling agency – conducted in early March, showed TISZA with 33% support among all voters, compared with 29% for Fidesz-KDNP; among decided voters, the figures were 46% and 37% respectively (see Chart 1). Among the established opposition parties – including the liberal-left Democratic Coalition (DK), the centrist Momentum, the satirical Hungarian Two-Tailed Dog Party, the right-wing Jobbik, and the far-right Our Homeland Movement – only the latter currently exceeds the 5% electoral threshold. While the party landscape has polarised into a duopoly dominated by Fidesz-KDNP and TISZA, Our Homeland may prove pivotal in the upcoming elections, given its consistently stable support base of 6–7%.

Over the past year, all major polling agencies,[2] both government-affiliated and independent, have recorded rising support for TISZA, creating a new polling landscape. In recent independent surveys, TISZA’s lead has ranged from several,[3] to more than ten,[4] percentage points. Even state-controlled agencies have registered a significant increase in support for Magyar’s party, although Fidesz continues to lead in their surveys, due to methodologies favouring the ruling bloc.[5] TISZA’s current position in the polls largely stems from its success in attracting voters from the established opposition parties – which Magyar has shunned alongside Fidesz – to emphasise his commitment to offering a completely new political alternative. In response, the leadership of these parties has criticised him for his past association with the ruling party. In an act that underscored the marginalisation of Fidesz’s former opponents and marked the end of an era in Hungarian politics, Ferenc Gyurcsány – prime minister from 2004 to 2009 and Orbán’s principal rival after 2010 – announced in May that he was stepping down as DK chairman, relinquishing his parliamentary seat and withdrawing entirely from political life.

Chart 1. Support for individual parties among all voters and among decided voters

Source: Medián poll for HVG, March 2025.

Orbán on the back foot: a crisis year for Fidesz

The context in which Magyar emerged and surged in the polls was defined by scandals within Fidesz and the country’s mounting economic challenges. The pivotal event that paved the way for his entry onto the national political stage was the resignation of President Katalin Novák. The pardon scandal, which prompted one of Fidesz’s most prominent figures to withdraw from public life, was not the only reputational crisis the ruling party faced over the past year. On 25 September, one month before the commemoration of the 68th anniversary of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, Balázs Orbán, the political director in the Prime Minister’s office, stated in an interview that in the event of a hypothetical Russian attack, the Hungarian government would not act as President Volodymyr Zelensky had done, describing Ukraine’s defensive actions as ‘irresponsible’. These remarks by a prominent adviser to the Prime Minister sparked a scandal, as they ran counter to the Hungarian right’s efforts to nurture the memory of the 1956 anti-Soviet uprising. Following this controversy, TISZA overtook Fidesz in some polls for the first time.

Fidesz is grappling with the waning appeal of its current narrative centred on foreign policy issues and the war. Its victory in the 2022 elections was largely driven by its efforts to instil fear in the population over the threat of a global armed conflict, along with its pledge that Hungary would remain uninvolved. At present, the government portrays Ukraine’s prospective accession to the European Union as the greatest threat to Hungary, which allegedly entails concrete ‘risks’ for society, primarily economic costs. These have been outlined in the questionnaire of the ongoing ‘national consultations’, a non-binding plebiscite used to shape public discourse and legitimise government policy.[6] The government also continues to rely on a permanent component of its narrative: criticism of Brussels and ‘liberal and globalist international networks’. Prime Minister Orbán’s recent speeches have focused on sharp criticism of the EU, which is increasingly portrayed as his camp’s primary Western adversary following the change of administration in the White House. Orbán has accused Brussels of seeking to overthrow the government in Budapest and replace it with a ‘puppet government’ – implicitly led by Magyar. Nevertheless, his government’s narrative, which portrays Magyar as a supposedly EU-controlled figure, has failed to stem his rising popularity.

In addition to internal party scandals and the declining appeal of Fidesz’s narrative, mounting economic difficulties have become a growing challenge for the government. For several months now, consumer inflation has topped the list of pressing concerns in public debate. After stabilising at approximately 3% in the final months of 2024, it rose again in January, reaching 5.7%, followed by 5.6% in February and 4.7% in March. The inflationary peak in 2023 reached 26%, setting a record within the European Union. Hungary also experienced the longest period of double-digit inflation within the bloc. Consequently, negative consumer sentiment has deepened further.

Weak economic conditions are also reflected in other macroeconomic indicators, including GDP, with the Hungarian economy contracting by 0.8% in 2023 and growing by only 0,5% in 2024, and a budget deficit exceeding 5.7% of GDP last year. The government promised that a recovery would begin in 2025, but a significant improvement appears unlikely: in May, the European Commission revised its forecast for Hungary’s GDP growth this year from 1.8% to 0.8%. In particular, the prospects are constrained by Hungary’s inability to access EU funds, two-thirds of which (c. €20 billion) remain frozen under the conditionality mechanism. The economic downturn has been felt in Hungary since 2020: while voters in the 2022 elections may still have remembered the eight years of relative prosperity between 2012 and 2019, the ruling Fidesz-KDNP coalition will no longer be able to rely on that memory in the 2026 campaign.

In the first months following his emergence on the political stage as a government critic, Magyar focused his efforts on organising anti-government protests, the largest of which drew crowds comparable to the mass demonstrations against the discredited Gyurcsány government in 2006.[7] In speeches delivered not only in Budapest but also in smaller towns seldom visited by government officials, the leader of TISZA has condemned abuses of power and oligarchic networks linked to Fidesz. In particular, he has denounced those affiliated with the National Cooperation System (NER), which since 2010 has played a key role in entrenching the institutional foundations of Hungary’s political system. Magyar has centred his criticism on domestic issues, arguing that Fidesz has ‘forgotten’ them as it focused on global affairs and its ongoing confrontation with EU institutions.

Following the 2024 European Parliament elections,[8] Magyar turned his attention primarily to highlighting the areas of Hungarian public life that have been dysfunctional under the current government. During the summer lull in political activity, he set the tone of public debate by touring the country, visiting public institutions such as hospitals and foster care facilities and exposing their dire condition through his social media channels. He remains highly active on these platforms, which serve as his main channel of communication with supporters.

Magyar’s one-man political show

For a long time, Magyar focused on a high-profile campaign criticising the government and the domestic situation without presenting a coherent policy platform for TISZA. The ‘21 demands’ he put forward on 15 March 2024 contained only very general statements. He mainly signalled that he would seek to hold the current government accountable, raise living standards for Hungarians, pursue a pro-European agenda, and improve the country’s international reputation. A few more concrete proposals were presented during TISZA’s commemoration of the 1956 revolution last October. On that occasion, Magyar declared that after the elections he would endeavour to unblock EU funds, suggesting that an investigation by the European Public Prosecutor’s Office into the current government’s alleged misuse of public funds could facilitate this process. He also pledged to reform the education and healthcare systems, introduce a constitutional limit of two terms for the office of prime minister (a clear reference to Orbán, who is currently serving his fourth consecutive term and fifth overall), raise the minimum wage, and maintain existing family benefits, 13th-month pension payments, and reduced household energy tariffs.

The party is expected to develop its full programme through public consultations, which have been ongoing since last December, with the input of 65 thematic working groups. On 15 February, TISZA unveiled an outline of its programme at a party rally, shortly after entering full campaign mode at the start of the year (in his New Year’s address, Magyar called for early elections). The headline promises included freezing public debt, halting the sell-off of national assets, raising wages, indexing pensions, taxing the wealthiest individuals, creating separate ministries for rural development, health, and education (the interior ministry currently oversees the latter two), decentralising the state, increasing budgetary allocations for the healthcare system, enhancing education quality, restoring university autonomy, constructing residential care homes, and supporting the manufacturing sector, farmers, and small and medium-sized enterprises.

Thus far, TISZA’s leader has said little on Ukraine and the war, an issue that has been almost entirely dominated in Hungary by Fidesz’s ‘peace’ narrative, which frames any expression of support for Ukraine as ‘war-mongering’. Last July, Magyar travelled to Kyiv to personally deliver aid collected for a children’s hospital bombed by Russian forces, but in October MEPs from his party abstained from voting on a resolution to provide financial assistance to Ukraine. At a congress of the European People’s Party (EPP) last April, they also withheld support for a resolution backing Ukraine’s accelerated accession to the EU – a decision which Magyar justified by asserting that Ukraine had not fulfilled the accession criteria.

This restraint appears to stem from a purely pragmatic political calculation. Had Magyar supported assistance to Ukraine, the Orbán government would likely have accused him of seeking to ‘drag the country into the West’s war with Russia’ or to bring Ukraine into the EU. Such claims could alienate Fidesz voters, who have been heavily influenced by state propaganda on this issue and whom the opposition leader has been actively courting. After 58% of respondents in TISZA’s survey, conducted in response to Fidesz’s ‘national consultations’, declared support for Ukraine’s accession, Magyar pledged to hold a referendum on this matter if he wins the election. It also remains unclear how he would approach Hungary’s relations with Russia should he come to power. In a January interview with Reuters, he stated that his policy would be ‘pragmatic’, adding that the flagship project of Hungarian-Russian energy cooperation – the expansion of Hungary’s Paks nuclear power plant by Russia’s Rosatom – cannot realistically be suspended at this stage, although he did call for its ‘renegotiation’.

So far, the movement of voters from Fidesz to TISZA has been minimal. The new party’s support base consists primarily of voters who previously backed the traditional opposition, many of whom have now moved to TISZA, as well as the undecided. However, the experience of the 2022 elections shows that Fidesz has greater reserves of support within the latter group. This means that while Magyar has succeeded in consolidating the electorate of the older opposition parties, he still faces the challenge of winning over the undecided and attracting at least a portion of the ruling party’s supporters. When preferences are broken down by age and place of residence, TISZA trails Fidesz most clearly among older voters (over 65) and residents of small towns. Reaching these groups will require addressing different topics, employing new forms of communication, and above all, building a robust nationwide party infrastructure.

The organisational base of the new party’s supporters consists of so-called ‘TISZA islands’ – more than a thousand local associations across Hungary and abroad, collectively comprising tens of thousands of people. However, these are not formal party structures. Since October, TISZA has been recruiting members, prospective candidates for the 106 single-member constituencies, and professionals to form its expert support base. Applications are submitted online, in a process that opposition-linked media outlets have likened to a talent show casting. Until recently, Magyar’s camp lacked professional politicians; his public appearances were predominantly accompanied by artists and celebrities. A turning point came in mid-February, when Romulusz Ruszin-Szendi, the former Chief of the Hungarian General Staff who was dismissed from his post in 2023, appeared at a TISZA rally.

Déjà vu from 2021 and the aces up Orbán’s sleeve

The public enthusiasm surrounding Magyar’s recent polling performance recalls the mood ahead of the April 2022 parliamentary elections. At that time, six ideologically diverse opposition parties united to form what was meant to be a credible counterweight to Fidesz. The new bloc managed to select a joint leader and candidate for prime minister, Péter Márki-Zay. In the final months of 2021, polls indicated that the United for Hungary coalition enjoyed greater support than the ruling party. Ultimately, however, the Fidesz-KDNP coalition secured a landslide victory with 53% of the vote, while the opposition alliance garnered only 35% and even failed to strip Fidesz of its constitutional majority in parliament. Analysts pointed to the opposition’s insufficient internal consolidation (the alliance was formed with the aim of defeating Fidesz rather than governing together) and Márki-Zay’s lack of leadership stature as key factors in the defeat. Today, the situation is different in these respects: Fidesz now faces a single party with a strong leader. However, the systemic realities remain unchanged. The disproportionate electoral system continues to favour Fidesz, which, as the party of power, also has significant capacity to offer pre-election incentives and mobilise its base.

Fidesz designed the electoral system in such a way as to secure a parliamentary advantage even with a minority of the vote. In elections to Hungary’s unicameral parliament, voters cast two ballots: 106 MPs are elected in single-member districts, while the remaining 93 are chosen from party lists. The electoral law adopted in 2011 strengthened the majoritarian component (where a simple plurality is sufficient to win a district) and introduced the so-called compensation mechanism, which reallocates ‘unused’ votes from districts to those cast for candidates on national lists. In practice, the system is highly disproportional and strongly favours the winning party. This enabled Fidesz to secure a two-thirds parliamentary majority with just 44% of the vote in 2018 and 53% in 2022.

Should Orbán’s party conclude that TISZA’s lead is sustainable and that it might benefit from the electoral system originally tailored to favour Fidesz, further amendments to the electoral law could follow. One solution discussed in the Hungarian press is the introduction of single-member constituencies for ethnic Hungarians voting in the neighbouring countries, a move that would increase the voting power of minority communities, which form a core part of Fidesz’s electorate. Another possibility would be to lower the electoral threshold to 3% (as it was until 1993), so that supporters of smaller opposition parties do not perceive their vote as wasted and choose these parties over TISZA.

The approaching elections will likely prompt the government to deploy familiar methods of maintaining support through social benefits. It has already announced a number of measures for the coming year, including additional housing subsidies for families, VAT refunds on a range of food products for pensioners, and lifetime income tax exemptions for mothers with two or more children. The ruling camp also benefits from its dominance in the media landscape: approximately 78% of the market is controlled by individuals affiliated with Fidesz,[9] enabling it to freely shape the pre-election discourse. After a decade of politicising public broadcasters, the government has in recent months intensified pressure on independent media, which are now largely confined to the Internet. The law on the ‘defence of sovereignty’, passed in December 2023, allows for the surveillance of media outlets and NGOs as well as penalties for receiving foreign funding. The change of administration in the White House and the suspension of USAID assistance programmes have provided the government in Budapest with an opportunity to advance its campaign against recipients of US financial support. In his State of the Nation address last February, Orbán announced the appointment of a government commissioner who would travel to the United States to collect data on organisations that had previously benefitted from such support.

Prospects

Magyar’s most notable successes include sidelining the traditional opposition, forcing Fidesz to respond to his agenda in public debate, primarily through social media, and introducing a new quality in the style of communication with voters. At the same time, he now finds himself at a point where merely highlighting the government’s mistakes may no longer be sufficient to retain public attention, especially in the absence of an appealing programme and clear positions on many key issues. He also faces the challenge of establishing party structures across the country and reaching Orbán’s most loyal electorate: elderly people living in more than 2,000 of the country’s smallest towns who do not use the Internet. Their votes are likely to be decisive in next year’s elections. It appears that the key task for the new opposition leader is not only to communicate effectively with potential voters but, above all, to engage in painstaking grassroots work and to build a national party infrastructure.

In the current situation, Fidesz’s main challenge lies in the country’s poor economic condition, which the government has sought to blame on international circumstances, namely the war and sanctions. However, a growing number of Hungarian people, facing declining living standards, appear increasingly aware that the quality of life in Hungary is beginning to fall behind that of neighbouring countries. A closer look at support for Fidesz over the years reveals that it peaked during the period of economic prosperity between 2013 and 2019, when Hungary’s middle class expanded rapidly. A year and a half ahead of the elections, the government began making electoral promises centred on tax relief and social benefits, targeting primarily its core electorate. However, fulfilling these pledges is hampered by the current state of public finances and the scant prospects for unfreezing the EU funds that have been withheld under the conditionality mechanism.

A victory for TISZA in the next parliamentary elections in the spring of 2026 would likely be attributable to both Magyar’s new political offer and the declining popularity of Fidesz, which has been grappling with reputational issues and the country’s poor economic situation. However, even under such circumstances, TISZA is unlikely to secure a constitutional majority. Hungary’s legal framework established by the second Fidesz government includes approximately 70 so-called cardinal laws governing key areas of state activity, which require a qualified two-thirds majority to be amended. In practical terms, this means that even if Magyar were to become prime minister, he would most likely be unable to implement the systemic reforms he has pledged. Fidesz would retain many tools for preserving its resources and obstructing the actions of the new government.

APPENDIX

Profile of Péter Magyar

Péter Magyar (born in 1981 in Budapest) comes from a family with legal and political traditions. His mother served as Secretary General of the Supreme Court and as Vice-President of the National Judicial Office (OBH). His grandfather was a Supreme Court judge; his grandmother’s brother was Ferenc Mádl, President of Hungary from 2000 to 2005. In 2004, Magyar graduated from the Faculty of Law at the Péter Pázmány Catholic University in Budapest. He began his career as a judicial assistant at the Metropolitan Court before moving to the private sector, where he advised foreign companies on investments in Hungary. Following Fidesz’s rise to power in 2010, he worked at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A year later, during Hungary’s EU presidency, he was posted as a diplomat to the Permanent Representation of Hungary in Brussels. From 2015, he worked in the Prime Minister’s Office, where he was responsible for maintaining relations between the government and the European Parliament. Between 2018 and 2024, he held a number of executive roles in state institutions and companies, including the Hungarian Development Bank (MFB), the Student Loan Centre, Hungarian Public Roads (MKNZRT), and the Volánbusz transport company. From 2006 to 2023, he was married to Judit Varga, with whom he has three children. Beginning in 2019, Varga served as Minister of Justice; she resigned in 2023 following her decision to run as the lead candidate for the Fidesz-KDNP list in the European Parliament elections.

[1] See I. Gizińska, ‘Hungary: resignation of President Novák’, OSW, 13 February 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[2] Publicus, Medián, Závecz, IDEA, Századvég, Alapjogokért Központ, Nézőpont, Republikon, 21 Research Center.

[3] A lead of five percentage points among all voters and nine percentage points among decided voters, according to the March 2025 Medián poll.

[4] A lead of 14 percentage points among decided voters, according to the April 2025 poll by 21 Kutatóközpont.

[5] According to a poll conducted last March (at the same time as the Medián survey) by Nézőpont, a government-affiliated research institute, 37% of respondents supported the ruling party, while 25% backed TISZA. Nézőpont assesses party preferences among active voters, both those who explicitly declare their choices and those identified through statistical methods among undecided or concealed voters. Based on this, it estimates the ‘most probable result for the list’. According to projections derived from the March poll, the ruling party would be unable to retain its two-thirds constitutional majority.

[6] See I. Gizińska, A. Sadecki, ‘Hungary hardens its stance on Ukraine’, OSW, 28 March 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[7] See idem, ‘The ‘Rise up, Hungarians’ movement: a new challenge to Fidesz’s domination’, OSW, 10 May 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[8] See I. Gizińska, ‘Hungary elections: Fidesz’s victory overshadowed by the new opposition’s success’, OSW, 13 June 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[9] A study conducted by Mérték Médiaelemző Műhely in 2019.