Russian coal on the global market: difficulties and weak prospects

The EU embargo on Russian coal and the resulting need to redirect its supplies to other markets have significantly exacerbated the problems faced by Russia’s coal sector, which is finding it increasingly challenging to generate the expected export revenues. The low profitability of foreign sales is affecting the operation of the industry, as it is grappling with a crisis despite relatively high global coal prices. Breaking this negative trend appears unlikely, as the insufficient competitiveness of Russian companies stems from structural factors.

Export difficulties herald stagnation in the sector and undermine the prospect of meeting state targets for increasing the extraction and sale of coal. At the same time, they signal that a thorough transformation of the industry is necessary. Enhancing the competitiveness of Russian companies on the global market requires long-term investment in infrastructure, which in itself will not guarantee the profitability of a significant part of the sector. The situation of coal companies is further complicated by global decarbonisation trends and the strong competitiveness of other exporters in Asia. The negative momentum also carries consequences for the state, raising questions regarding the justification for subsidising the coal industry.

The sector’s crisis and production stall

Since 2024, Russian media have described the situation in the country’s coal sector as a ‘crisis’, highlighting the unprofitability of coal extraction in the Russian Federation. This has become particularly acute since global coal prices began to stabilise following the surge in 2022.[1] The industry is struggling with financial losses resulting from the inability to achieve sufficient margins on foreign sales. According to figures compiled by the Russian Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat), in 2024 over half of the sector recorded a net loss, while three years earlier the share of companies ‘in the red’ was only around 30%. Last year, the total net loss recorded by the sector as a whole amounted to 112.6 billion roubles (approximately $1.3 billion).

Chart 1. Total financial performance of the coal sector, 2021–2024

Source: Rosstat.

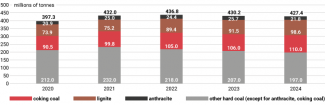

Since 2023, a slight decline in extraction has also been recorded, effectively indicating stagnation. In 2018–2019, Russian companies reached a historic production peak – a level of 439 million tonnes annually. Since then, production has remained at around 430 million tonnes annually, excluding the pandemic year of 2020.

Chart 2. Extraction of various types of coal, 2020–2024

Source: Rosstat.

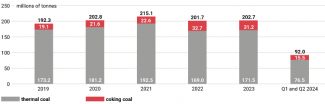

The situation is slightly different in the case of foreign sales. Over the past few years, the industry has recorded a decline in exports twice – in 2022 and in 2024. In both instances, the volume of coal sold fell by approximately 8% year-on-year. According to information from the Ministry of Energy, in 2024 coal sales shrank by 7.9%, to 196.2 million tonnes, a figure also confirmed by data from CDU TEK for the first half of the year.[2] The weaker performance is mainly due to a declining volume of thermal coal sales, while coking coal export volumes remained stable.

Chart 3. Coal exports,2019–2024

Source: CDU TEK.

The negative trend in exports heralds a halt to further growth in extraction, which had been steadily increasing since the 1990s. Foreign sales were the main driving force behind the entire sector, as evidenced by the pace of rising export volumes. Between 2000 and 2023, total coal exports increased from around 38 million tonnes to over 200 million tonnes. At the same time, the domestic market became less important for the sector – in 2011, domestic deliveries accounted for approximately 65% of all coal extracted in Russia, whereas by 2023, this figure had dropped to just around 48%. The share of coal in Russia’s energy mix has also been declining. While at the beginning of the 21st century coal accounted for 20% of energy generation, since 2020 only about 13% of electricity has been produced from coal. A slight decrease in overall consumption has been recorded (with an increase in metallurgical use), and future forecasts predict stagnation, particularly for thermal coal.[3]

Russian exports play a significant role in balancing the global coal market. According to IEA data, in 2024 Russian companies accounted for approximately 13.5% of global trade in terms of volumes sold,[4] making Russia the third largest exporter of coal after Indonesia and Australia. This share has declined over the past few years – as recently as 2019, Russia’s share in the global market was 18%.

Russian policymakers continue to assert their intention to enhance the country’s role as a coal exporter. According to the state energy strategy published in April this year (Energostrategy-2050),[5] Russia is set to expand its share of the global coal market in two stages: to 21–23% by 2036, and then to 24–27% by 2050. Under the inertia scenario, which assumes the continuation of current trends without new investments in sector development, Russia projects that exports will reach 288 million tonnes by 2036 (an increase of approximately 70 million tonnes compared to 2023), while production will rise to 545 million tonnes (approximately 100 million tonnes more than in 2023). These figures indicate that policymakers are also factoring in domestic sales, and thus higher domestic consumption. However, these assumptions contradict the forecasts of Russian analysts, who predict stagnation in domestic demand for coal and a potential increase in exports, primarily due to rising sales of coking coal.[6]

Chart 4. Scenarios for Russian coal extraction according to Energostrategy-2050

Source: Ministry of Energy of the Russian Federation.

Chart 5. Scenarios for Russian coal exports according to Energostrategy-2050

Source: Ministry of Energy of the Russian Federation.

The impact of sanctions

Since 2022, Russia’s coal sector – like its oil and fuel industry – has been grappling with Western sanctions. These restrictions have significantly hampered its operations, affecting logistics, export markets, and financing. By 2025, US Treasury Department designations had targeted half of the entire sector,[7] including the largest coal producer – the SUEK conglomerate, which in 2023 accounted for a quarter of national production. Consequently, the purchase of Russian coal by entities from third countries has become far less likely due to the risk of secondary sanctions from the United States, which would also create complications in processing transactions.

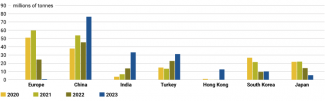

However, the most significant element of Western restrictions is the EU embargo on coal, along with a reduction in imports by several Asian countries (Japan and South Korea). These constraints have led to a substantial decline in Russia’s coal sales since 2022. Consequently, Russia lost access to markets that previously accounted for nearly half of its exports. In 2021, Russia supplied almost 103 million tonnes of coal to European countries (including non-EU states), South Korea, and Japan. Just two years later, this volume had dropped to around 16 million tonnes (a decrease of approximately 85%). Sales to Europe ceased almost completely, while exports to South Korea fell by as much as 50% and to Japan by 75%.

As a result of Western restrictions, as with oil and fuels, Russia was compelled to redirect coal shipments to alternative markets. Compared to the export volumes recorded in 2021 and 2023, coal sales increased primarily in three directions: China (by 40%), India (by 500%), and Turkey (by 240%). While in 2021 Russia delivered 73 million tonnes of coal to these countries, by 2023 that figure had risen to 143 million tonnes. This accounted for almost 75% of the Russian Federation’s total coal exports.

Chart 6. Coal exports to selected destinations, 2020–2023

Source: author’s own analysis based on figures published by CDU TEK.

Transport limitations: by rail…

Sanctions have thus forced Russia to redirect its coal supplies to new markets, which has had a significant impact on the financial situation of the coal sector. According to media reports, the Ministry of Energy estimates the sector’s total losses since 2022 at almost 2.1 trillion roubles (approximately $23.7 billion), with more than half of that figure attributed directly to Western restrictions.[8] The sanctions regime has substantially intensified pre-existing problems that negatively affect the profitability of exports. These challenges stem from structural weaknesses, the most critical of which involves logistical problems.

A key factor reducing the competitiveness of Russian coal is the long export route to ports, which translates into high transportation costs that affect the final price of coal. The most intensively exploited coal deposits in Russia are located at a considerable distance from the seaports through which the vast majority of foreign sales are carried out.[9] Mines situated in the most significant coal basin – the Kuznetsk Basin (known as Kuzbass, which accounts for half of both extraction and exports) – are separated from ports by thousands of kilometres. Depending on the final destination, coal must be transported approximately 4,000 km to the port of Ust-Luga on the Baltic Sea, 4,600 km to the port of Tuapse on the Black Sea, or 5,700 km to the port of Vostochny on the Pacific Ocean. For comparison: coal fields in other key producing countries are located only tens or hundreds of kilometres from ports.

Table. Comparison of distances between coal fields and coal terminals of key coal exporters

Source: author’s own analysis based on figures compiled by N.Trans Lab.[10]

Moreover, due to newly established supply routes, half of the exported coal is currently transported through Asian terminals in Russia – owing to the shorter maritime distance to key coal recipients in Asia. This shift places additional strain on the rail network, as the distance between the coal field and the port must be covered via Russian railways, whose insufficient capacity represents yet another significant problem.

Although efforts are underway to increase the handling capacity of coal terminals, the pace of their modernisation is not being matched by Russian Railways (RZD), whose infrastructural limitations prevent the full utilisation of the export capacities of the country’s ports. This is reflected in usage statistics: in 2024, only 45% of the capacity of terminals in the European part of Russia was utilised, and 57% in the Asian part.[11] This situation stems from the insufficient transport capacity of the overburdened railway lines, which – despite ongoing investments – are unable to meet the demands of the Russian coal sector.[12]

Infrastructure limitations on coal exports present an objective barrier to export operations, despite the preferential treatment of this resource by the Russian authorities, who pressure Russian Railways (RZD) to offer discounts for these shipments. The national carrier classifies coal as a priority commodity, which results in the application of the lowest discounted freight rates to its transport. Moreover, certain coal-producing regions receive annual transport quotas – under agreements with the railway operator – specifically to facilitate coal exports to eastern destinations.[13] Due to this preferential status, coal accounts for a substantial share of rail transport (around 44% of total freight in 2021).[14] For comparison, the transported volume of exported Russian mineral fertilisers – a commodity that competes with coal for access to the railway network and is also shipped further from ports via bulk carriers – is several times smaller than the tonnage of exported coal.[15] Consequently, the mineral fertiliser sector does not overburden Russian railways to the same extent as the coal sector, while at the same time generating greater profit per tonne of transported cargo.[16]

According to industry representatives, coal transport costs can account for as much as two-thirds of its final price, depending on the location of extraction.[17] This is due to both the physical distance from ports and the limited capacity of the railway network. In a situation where global coal prices no longer guarantee high margins for exporters, the profitability of the sector is unclear, despite the preferential treatment it receives from the government. This is why the sector repeatedly calls for additional reliefs.[18]

…and by sea

Western sanctions have also hampered coal exports at the next stage of transport, namely the shipment of the commodity from Russian ports. Unlike in the case of oil, maritime coal transport is a far less profitable business. This is due both to the lower market value of coal compared to oil and to the logistical challenges involved in its transport. A similar situation applies to other bulk commodities that can be carried by the same vessels used for coal, such as wheat or mineral fertilisers. When a capesize bulk carrier is loaded to capacity, the value of the coal being transported is significantly lower than that of an equivalent tonnage of other bulk goods. This directly affects the final export margin for coal sellers.

The Western-imposed restrictions have increased delivery costs and intensified the competition faced by Russian suppliers. The EU embargo and the resulting loss of market access have also extended delivery routes – with limited railway capacity forcing Russia to export coal to Asian buyers even via European ports. Compared to previous sales to European countries, transport over significantly greater distances – such as to India – drives up the final cost of delivering the cargo. Deliveries to end recipients therefore take longer, reducing the total number of trips bulk carriers can make and consequently lowering the final transaction volume. Additionally, in the case of the western route (that is, to European ports), the coal sector does not receive subsidies for discounted transport, unlike the support provided for shipments to Asian ports.

The Russian sector demonstrates that under sanctions, profits from exports can only be achieved when shipments are made using the largest bulk carriers – capesize vessels. However, only large companies operate such vessels or have the capacity to accumulate sufficient capital to charter them for transporting their own cargo.[19] Moreover, not all terminals are equipped with the infrastructure necessary to accommodate such large ships.

Sanctions have also hindered cooperation between Russian companies and foreign shipowners and shipyards. A major issue is the insufficient size of Russia’s own fleet of bulk carriers, which largely consists of smaller vessels – making long-distance exports from Russia unprofitable with such ships. According to 2022 data, bulk carriers owned by Russian companies accounted for 30% of all foreign sales of bulk cargo – including not only coal, but also metal ores, fertilisers, and grain. Due to the limited number of such vessels, exporters are forced to bear the additional costs of chartering ships from other countries, which negatively impacts the overall profitability of Russian coal sales. Aware of these challenges, the authorities have allocated additional budgetary funds for the construction of new ships and the acquisition of used ones. However, tangible results of these initiatives will only emerge over time, due to factors such as strong competition among shipowners purchasing vessels and production constraints in Russian shipyards.[20]

New export dependences

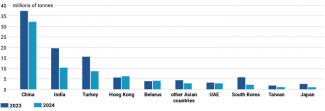

The EU embargo and the need to redirect coal deliveries have also deepened Russia’s export dependence on two countries – China and India. Between 5 December 2022 and February 2025, these countries accounted for 45% and 18% respectively of Russia’s total coal sales.[21] In theory, these markets might appear to be relatively secure destinations for continued exports, as forecasts suggest rising consumption driven by factors such as the expansion of coal-fired power plants and energy-intensive industries. However, it should be noted that the rate of demand growth for coal differs between the two countries. Nevertheless, last year’s decline in Russian coal exports to these destinations suggests that these favourable developments are insufficient to offset other factors negatively affecting the outlook for this trade.

Chart 7. Coal exports to selected countries in the first half of 2023 and 2024

Source: CDU TEK.

The competitiveness of Russian coal on the Indian and Chinese markets is relatively low due to the previously discussed challenges. The situation is further exacerbated by the energy policies of these key importers. In both countries, domestic coal production is increasing,[22] reflecting their intention to maintain or enhance energy security.[23]

Moreover, Russia’s coal exports are also being reduced by protectionist measures introduced by importers – for example, China’s reinstatement of tariffs on coal from the Russian Federation,[24] which led to a decline in volumes sold to that country. Another important factor is China’s replacement of Russian coal with Australian coal, following the lifting in 2023 of its unofficial embargo on imports from Australia.[25] At the same time, Russia is now forced to compete in Asia with other key exporters – Indonesia and Australia – to a much greater extent than it did in Europe. This is due to the shorter delivery routes from those countries.

Conclusions: painful transformation is necessary to maintain export profitability

The difficult situation of the Russian coal sector, resulting from the exacerbation of its structural weaknesses by Western sanctions, became fully apparent only in 2023, when the industry recorded a significant decline in profitability – despite the fact that the EU embargo had already been introduced a year earlier. In 2022, the impact of the sanctions was mitigated by record-high coal prices, which allowed comfortable margins despite the sanctions pressure. However, this was an exceptional circumstance, triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which intensified the energy crisis and disrupted parts of the global commodity market. Once coal prices stabilised – with 2024 levels returning to those seen before the invasion – export profitability dropped sharply. Consequently, the Russian coal sector posted a negative net result last year.

Chart 8. Average price of Australian coal (Newcastle FOB), 2018–2026[26]

Source: author’s own analysis based on figures compiled by the World Bank.

In the medium and long term, a renewed increase in coal prices driven by structural, and therefore lasting, factors appears unlikely. While there is the prospect of rising demand for coal in developing countries, decarbonisation trends among developed economies mean that overall global demand is expected to decline. Thus, forecasts indicate a gradual decrease in prices in 2025–2026,[27] as well as a flattening of supply, with peak production expected in 2027. The International Energy Agency contends that prices will remain high enough for producers to continue earning revenue from their operations for some time – with the notable exception of Russian companies, whose product is simply uncompetitive on the global market.[28]

The profitability of coal exports from Russia could be improved by addressing existing challenges – primarily the infrastructure bottlenecks. However, doing so would require significant investments from the state and the long-term implementation of such projects, and even then, it would not guarantee a full recovery of the sector. At the same time, it is difficult to imagine that Russia will actually achieve its ambitious targets for further increases in export volumes. Already, it has become evident that, despite relatively high coal prices, companies are being forced to limit exports due to the unprofitability of transporting coal. With global demand for coal continuing to decline, the key challenge for the Russian coal sector will be to maintain its current share in international trade. Increasing that share, especially given the current pace of growth among major producers (Australia, Indonesia) and importers (China, India), appears particularly unlikely.

The implications of these difficulties extend beyond the condition of the coal companies themselves. Although the coal industry accounts for only approximately 0.8% of Russia’s GDP (for comparison, the oil and gas sector contributes approximately 16.5%), it plays a significant role in the functioning of 29 monotowns built around coal mining, especially in the Kuznetsk Basin (Kuzbass) region. In 2023, the coal sector directly employed 142,000 individuals,[29] with almost 100,000 working in Kuzbass alone. In addition, substantial numbers of workers are employed in industries that rely on coal (such as metallurgy and combined heat and power generation), as well as in companies involved in logistics and transport operations related to coal deliveries. In Russia, the total number of individuals whose livelihoods are indirectly tied to the coal sector is estimated at several hundred thousand.

In this context, a comprehensive restructuring of the entire coal sector cannot be ruled out, as it is also likely to face declining domestic demand, driven in part by Russia’s ongoing gasification efforts. Low profitability will lead to the closure of thermal coal mines located far from export markets, such as those in the Kuznetsk Basin. At the same time, the sector will be sustained by large companies with sufficient capital to extract coal from deposits situated closer to export terminals.[30] On international markets, companies specialising in coking coal exports are also expected to remain active, as demand for this type of coal is not projected to decline as rapidly as that for thermal coal. The coal sector’s unprofitability and the resulting need to scale back parts of its operations will confront the Russian authorities with a dilemma regarding the justification for continuing to subsidise it.

[1] ‘"Кризис только начинается". Доля убыточных угольных предприятий в России возросла до 52%’, Сибирь.Реалии, 13 August 2024, sibreal.org.

[2] A comparison of the cited CDU TEK statistics with those for H1 2023 suggests that the decline could have been greater, amounting up to approximately 10%.

[3] Е. Кузнецова et al., ‘Будущее угольной индустрии: рынок России до 2050 г.’, Яков и Партнёры, April 2023, yakovpartners.ru.

[4] Coal 2024. Analysis and forecast to 2027, International Energy Agency, December 2024, iea.org.

[5] ‘Энергетическая стратегия Российской Федерации на период до 2050 года’, Ministry of Energy of the Russian Federation, 12 April 2025, minenergo.gov.ru.

[6] Е. Кузнецова et al., ‘Будущее угольной индустрии: экспортный потенциал России до 2050 года’, Яков и Партнёры, August 2023, yakovpartners.ru.

[7] See Coal 2024. Analysis and forecast to 2027, op. cit.

[8] В. Милькин, Г. Бичашвили, А. Волобуев, ‘Минэнерго оценило потери угольной отрасли в 2 трлн рублей’, Ведомости, 2 April 2025, vedomosti.ru.

[9] According to figures for 2023, 91.7% of coal exports were carried out via ports. See Д. Губанов, Г. Мешков, И. Петренко, ‘Итоги работы угольной промышленности России за 2023 год’, Уголь, 2024 (3), p. 18–29, after: cyberleninka.ru.

[10] See Highway to Hell: Перспективы угольной промышленности России, N.Trans Lab, October 2024, stolypin.institute.

[11] В. Елетина, ‘Морские порты для перевалки угля в 2024 году оказались недозагружены’, РБК, 28 January 2025, rbc.ru.

[12] For more see I. Wiśniewska, Pivot to the east. Russia’s transport policy, OSW, Warszawa 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[13] In 2025, these transport quotas were only provided to Kemerovo oblast.

[14] See Highway to Hell: Перспективы угольной промышленности России, op. cit. In 2024, foreign sales of Russian fertilisers, which are another type of bulk goods transported in a similar way to coal, accounted for 5% of Russia’s total exports value.

[15] In 2024, Russia exported 42 million tonnes of mineral fertilisers.

[16] In 2022–2023, coal accounted for approximately 6% of Russian exports in terms of value. The figure is similar for mineral fertilisers.

[17] Е. Зайнуллин, ‘Уголь на пороге кризиса’, Коммерсантъ, 23 April 2024, kommersant.ru.

[18] О. Войцеховская, ‘Уголёк или жизнь. Проблемы отрасли выходят за рамки отношений угольщиков с РЖД, скидок и квот’, Vgudok, 18 December 2024, vgudok.com.

[19] Е. Зайнуллин, ‘Дешевому углю — большое судно’, Коммерсантъ, 10 January 2023, kommersant.ru.

[20] K. Сергеев, ‘Крупнотоннажный флот России: ставка на сэкондхэнд?’, Корабел.ру, 23 March 2023, korabel.ru.

[21] P. Katinas, V. Raghunandan, ‘February 2025 — Monthly analysis of Russian fossil fuel exports and sanctions’, Centre for Research on Energy and Clear Air, 14 March 2025, energyandcleanair.org.

[22] ‘China’s Coal Output Hits a Record and Fuels Oversupply Concerns’, Bloomberg, 16 December 2024, bloomberg.com; ‘India hits record 1 billion tonne coal production this fiscal year’, The Economic Times, 21 March 2025, economictimes.indiatimes.com.

[23] See M. Kalwasiński, ‘China on the road to ‘green’ energy security’, OSW Commentary, no. 605, 7 June 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[24] A. Shaw, ‘China reinstates coal tariffs threatening Russian exporters’, Power Technology, 2 January 2024, power-technology.com.

[25] C. Howe, ‘China buys less Russian coal in 2024 despite record imports’, Reuters, 20 January 2025, reuters.com.

[26] Coal valuation at Australia’s port of Newcastle is one of the most important indicators for its price fluctuations on Asian markets and serves as a major point of reference for global prices.

[27] See ‘Commodity Markets’, World Bank, worldbank.org.

[28] See Coal 2024. Analysis and forecast to 2027, op. cit.

[29] Д. Губанов, Г. Мешков, И. Петренко, ‘Итоги работы угольной промышленности России за 2023 год’, op. cit.

[30] The Elga project in Sakha is one such initiative, enabling the extraction of coking coal at the Elga Coal Complex. It is expected to operate its own railway line and a coal terminal in Khabarovsk Krai, on the Sea of Okhotsk. The port’s construction is almost complete. Plans have been made to export 15 million tonnes of coal via this facility in 2025.