Agency on credit: Germany releases the debt brake

The amendment to Germany’s Basic Law, enabling increased spending on defence and infrastructure investments, should be seen as a key element of the changes initiated in the country following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 – albeit a step taken three years too late. The outbreak of full-scale war proved to be an insufficient catalyst for reform in Germany. Only the growing uncertainty regarding the consequences of the policies pursued by the new US president, Donald Trump, ultimately spurred Germany into action. The decision to circumvent the constraints of the debt brake has paved the way for the formation of a CDU/CSU-SPD government, but it does not guarantee the success of state reform. Nonetheless, the future coalition’s politicians have undoubtedly secured the financial capacity to implement their agenda, addressing a long-standing gap.

The adopted investment package and the planned increase in defence spending are intended to stimulate Germany’s stagnant economy, support the modernisation of its broadly defined infrastructure – from railways to energy grids and fibre-optic networks – improve equipment levels and streamline the Bundeswehr, and help defuse various social and political tensions within the country. However, the impact of the infrastructure fund on economic growth may be limited by labour shortages and excessive bureaucracy, including at the local government level. Similar obstacles – a lack of volunteers for military service and overly complex military procurement procedures – may also hinder efforts to strengthen Germany’s armed forces.

Should the announced reforms succeed, Germany is likely to use its regained economic strength and increased defence spending to improve its negotiating position, particularly in talks with its partners in the United States and Europe. This could support its ambition to reclaim a leadership role within the EU.

On 18 March, the outgoing Bundestag adopted an amendment to the Basic Law, altering the debt rules concerning defence spending and infrastructure investments. 512 of the 733 deputies voted for the proposal put forward by the CDU/CSU, SPD and the Greens, while 206 MPs from the AfD, FDP, BSW, and The Left voted against. On 21 March, the Bundesrat approved the amendment, with 53 of the 69 votes in favour. Amending the Basic Law requires a two-thirds majority in both the Bundestag and the Bundesrat. During the upcoming parliamentary term, passing the amendment would have required an agreement with either the AfD or The Left, both of which have opposed it and are likely to challenge the procedure of its adoption before the Federal Constitutional Court. The AfD rejects debt-financed investment, while The Left opposes borrowing for defence spending. Negotiations with either of these parties, particularly the AfD, are unacceptable to the other parliamentary groups; the CDU has even included a formal ban on cooperation with both parties in its statute. From the perspective of the CDU/CSU and SPD, which are set to form the new coalition, it was therefore crucial to secure the amendment’s passage by the outgoing Bundestag, through an extraordinary procedure, during the period after the election but before the new parliament convened. Securing the necessary two-thirds majority required negotiations with the Greens.

The amendment comprises three components. Firstly, it exempts spending on broadly defined defence exceeding 1% of GDP from the scope of the so-called debt brake – a fiscal rule incorporated into the German constitution during the 2009 global financial crisis to ensure the country’s financial stability.[1] Funds raised through additional borrowing will be allocated to modernising the Bundeswehr, improving civil defence, strengthening intelligence services, and supporting ‘countries attacked in violation of international law’, such as Ukraine.

Secondly, the amendment allows Germany’s federal states (Länder) to take on new debt of up to 0.35% of GDP.[2] Under the debt brake, since 2016, the federal government’s annual structural deficit has been limited to 0.35% of GDP; since 2020, the Länder have been strictly prohibited from incurring new net debt. The pandemic, Russia’s war against Ukraine, and the prolonged economic stagnation have revived the debate over the rationale for this restriction. Diverging views on the issue ultimately led to the collapse of the SPD–Greens–FDP coalition.

The amendment’s third component is the establishment of a 12-year, off-budget fund worth €500 billion to finance additional investments in infrastructure and climate projects, on the condition that at least 10% of the core budget is allocated to investments. Of this total, €100 billion will be allocated to the Länder, while another €100 billion will be earmarked for climate policy.

Success for the incoming coalition

The amendment’s adoption represents a success for the CDU/CSU and SPD, paving the way for the formation of a coalition government led by Friedrich Merz. It also removes one of the most contentious issues in German politics and a constant source of tension in the previous government – the question of how to finance spending on infrastructure investments, defence and military aid to Ukraine. The future coalition partners have also acquired the ability to allocate part of the regular budget to fulfilling their election promises while avoiding deep spending cuts.

Thanks to the amendment, each party has been able to advance elements of its political agenda. The Christian Democrats’ key priority was to secure additional funding for the Bundeswehr, free from fiscal constraints. They sought not only to enhance Germany’s overall security, but also to strengthen Chancellor-designate Merz’s negotiating position (through increased defence spending) in forthcoming talks with President Trump and European partners. The Social Democrats and the Greens, for their part, advocated reform of the debt brake in order to secure additional resources for investments and expand fiscal space for social spending. Despite joining the opposition after their poor showing in the Bundestag election, the Greens also retained the ability to continue the climate projects launched during the previous parliamentary term, and secured funding for new initiatives. Furthermore, all parties faced pressure from the Länder, which have long struggled with a chronic lack of investment funds amid a growing number of responsibilities, including those arising from migration policy. The possibility of assuming new loans will help ease these shortages.

A majority of Germans support above-average levels of public borrowing, particularly for security-related purposes. Sixty-four per cent of respondents view the adoption of the constitutional amendment as the correct decision, including more than 80% of those who support the CDU/CSU, SPD, and the Greens (Politbarometer survey for ZDF, 20 March). The off-budget investment fund has generated less enthusiasm. While half of those surveyed assess it positively, 27% consider the amount earmarked excessive, and 15% reject the very notion of incurring debt for investment purposes. This group is dominated by supporters of the Christian Democrats, 44% of whom say they feel betrayed by their own leader. This sentiment is reflected in the polls. Since the election, support for the CDU/CSU has declined, while the AfD has continued to gain ground, edging past the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU – 24%, AfD – 25%, according to an Ipsos poll from 9 April). Throughout the campaign, Merz argued that streamlining the Bundeswehr and repairing infrastructure could be achieved without new borrowing, simply by cutting social spending and reducing the costs of migration policy. After the election, however, he abruptly changed course, citing a shift in US policy under President Trump as justification. In reality, Merz had long understood that Germany’s modernisation plans, including efforts to strengthen defence and generate renewed momentum for the economy, could not succeed within the confines of the regular budget.

The end of the Bundeswehr’s problems? Yes, but…

The decision to ease debt limits on defence spending has resolved the issue of how to secure stable funding for the Bundeswehr’s growing needs, a crucial factor enabling Germany to meet its commitments under NATO’s New Force Model.[3] The establishment of a special €100 billion fund for the German armed forces in February 2022, which is expected to be exhausted by 2027, enabled an increase in defence spending from €52.4 billion to €90.6 billion ($95.91 billion) in 2024.[4] As a result, for the first time since 1990, Germany’s defence spending exceeded 2% of GDP, reaching 2.1%. This was achieved by combining the budget of the Ministry of Defence (€52 billion), resources from the special fund (€19.8 billion), funding for military aid to Ukraine (€7.5 billion), and other expenditure classified by Germany as defence-related (€11.4 billion).[5]

The additional defence funding is intended to enable Germany’s security apparatus to adapt to current challenges: Russia’s aggressive policy and the risk of reduced US military engagement in Europe. Firstly, the new funds will allow the armed forces to meet their immediate needs: replenishing ammunition stocks, replacing equipment supplied to Ukraine, fully equipping units, and strengthening the country’s air defences.[6] In addition, the CDU/CSU and SPD have outlined plans to modernise the Bundeswehr and equip it with advanced technologies: expanding cyber capabilities, upgrading communications systems, and investing in artificial intelligence and unmanned systems. According to preliminary estimates, €150 billion will be required to fund projects in this area alone.[7]

Secondly, the federal government will be able to allocate significantly more funding to increasing the size of the armed forces. According to plans by the Ministry of Defence, the Bundeswehr is expected to expand from 183,000 to 203,000 soldiers by 2031. However, this will require additional funds for salaries for new military and civilian personnel, as well as investment in the requisite infrastructure.[8]

Thirdly, the amendment to Germany’s Basic Law provides the government with the resources to implement the Operationsplan Deutschland (Germany Operational Plan). In the event of Russian aggression against NATO, one of Germany’s tasks would be to ensure an efficient system for transporting allied forces.[9]

Fourthly, the German government will gain financial flexibility to increase military assistance to Ukraine – a crucial factor given the uncertainty surrounding future support from the United States. In late 2024 and early 2025, the Chancellery repeatedly delayed the transfer of an additional €3 billion to Ukraine, arguing that it would necessitate cuts in other areas. Ultimately, the Bundestag’s budget committee, at the request of the Ministry of Finance, approved the release of these funds in March.

Making effective use of the new funding for the Bundeswehr will not be feasible without completing the reform of the procurement system initiated by Defence Minister Boris Pistorius (SPD). Another challenge stems from the limited production capacity of Germany’s defence industry. At present, it accounts for just 0.3% of Germany’s GDP.[10] On the list of the world’s largest arms producers, Rheinmetall is the highest-placed company with exclusively German capital, ranked 23rd with an annual turnover of $5.5 billion.[11] Currently, companies such as the navigation systems manufacturer Hensoldt and the tracked vehicle gearbox producer RENK are in discussions to recruit staff from civilian plants planning job cuts. Other businesses may follow the example of the KNDS consortium, which acquired a factory in Görlitz from the French train manufacturer Alstom in February, and plans to manufacture parts for Leopard tanks there.

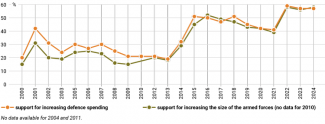

The German government also faces the problem of staffing shortages in the armed forces. The number of professional and contract soldiers has been falling since 2020 (see Chart 1). The Christian Democrats have proposed reintroducing mandatory military or civilian service to address this gap, but the SPD has consistently opposed this measure, insisting that military service should remain voluntary.[12] Ultimately, overcoming this challenge will require abandoning the so-called culture of military restraint, which developed particularly after the end of the Cold War in relation to overseas military operations, and is closely linked to the widespread anti-militarist sentiment within German society. This approach began to shift in response to events such as Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the onset of its aggression in the Donbas (see Chart 2).[13]

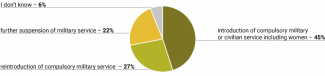

Public opinion polls indicate that 73% of Germans are concerned about security in Europe, 65% fear that Russia may attack additional European countries,[14] 27% support the reintroduction of mandatory military service, and 45% are in favour of introducing it either in the military or in social organisations, regardless of gender (see Chart 3). The decision to reform the debt brake, rather than to create a new special fund, is intended to safeguard investments against potential political crises or a takeover by parties opposed to such a radical shift, as any changes to the new rules would again require a two-thirds majority in both the Bundestag and the Bundesrat. However, this does not guarantee that future German governments will in fact utilise the fiscal space created by the CDU/CSU, SPD, and the Greens.

Chart 1. Structure of the Bundeswehr, 2000-24

Source: ‘Anzahl der Soldaten und Soldatinnen bei der Bundeswehr von 2000 bis 2024’, Statista, 26 February 2025, de.statista.com.

Chart 2. German attitudes towards increasing defence spending and funding for the Bundeswehr

Source: T. Graf, ‘Zwischen Kriegsangst und Kriegstauglichkeit. Sicherheits- und verteidigungspolitisches Meinungsbild in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 2024’, Zentrum für Militärgeschichte und Sozialwissenschaften der Bundeswehr, Forschungsbericht 137, 2024, p. 12, zms.bundeswehr.de.

Chart 3. German attitudes towards military and civilian service

Source: ARD-DeutschlandTREND April survey, Infratest dimap, April 2025, infratest-dimap.de.

An opportunity to bridge the infrastructure investment gap

Alongside increased borrowing for defence, another key component of the package is the establishment of a special, debt-financed fund for broadly defined infrastructure investments. It is intended to cover areas such as transport, energy, climate protection, education, healthcare, and digitalisation. Without the CDU/CSU’s consent to the establishment of this fund, the SPD and the Greens would not have supported a substantial increase in defence spending. By combining these two initiatives, lawmakers avoided framing defence and infrastructure investments as competing or mutually exclusive priorities. More importantly, however, the fund provides the government with an opportunity to address serious investment backlogs accumulated over recent decades. Largely due to inadequate funding, Germany’s overall infrastructure has steadily deteriorated in recent years, increasingly affecting the daily lives of its citizens. The financial needs are substantial: for example, investment required for the federal road network is estimated at €180 billion,[15] rail transport – €250 billion,[16] hospitals – €50 billion,[17] and schools and kindergartens – €67 billion.[18] In addition, the energy infrastructure associated with the Energiewende will require substantial investment: the total cost of expanding power grids alone is estimated at €650 billion.[19]

Allocating an additional €500 billion over a 12-year period will not resolve all of Germany’s investment backlogs, but it does offer a real opportunity to make substantial progress. Whether this opportunity is realised will depend on a number of factors. Firstly, it remains unclear how priorities will be set, which specific sectors will receive new funding, and to what extent they will benefit. The distribution of these funds has already become the focus of competing lobbying efforts by various sectors of the economy seeking to influence policymakers. Decisions on this matter will be taken by the incoming government as well as by future administrations.

It also remains unclear whether the planned funds can be utilised as intended. Past experience with other funding instruments, such as the Climate and Transformation Fund and the regular federal budget,[20] clearly demonstrates that a significant portion of allocated funds often remains unused. Major challenges include numerous regulatory and bureaucratic barriers, complex and lengthy procedures for planning investments and obtaining permits, as well as frequent legal complaints brought by local organisations in Germany, which often delay projects for months, if not years.

Further obstacles to investment delivery include shortages of skilled workers and the limited capacity of companies in sectors such as construction. Germany already has 1.5 million job vacancies, a figure that could rise to as many as 7 million by 2035.[21] Most economists agree that without far-reaching structural reforms, which are often politically difficult, the additional funds will either not be fully utilised or will be spent inefficiently, for instance on poorly selected projects or on consumption rather than investment.

Climate neutrality in the constitution

In the context of the newly established fund, the Greens secured at least two significant gains in negotiations with the CDU, CSU, and SPD. The first was the allocation of €100 billion, a full fifth of the planned resources, to the Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF), which is used to finance initiatives linked to the broader Energiewende agenda.[22] The second was the inclusion of the objective of achieving climate neutrality by 2045 in Germany’s Basic Law. While this was formulated as a legal condition for spending funds from the KTF, rather than a general objective of state policy, some legal experts argue that it could set an important precedent likely to influence future rulings by the Federal Constitutional Court in cases concerning national climate policy.

The injection of an additional €100 billion into the KTF over the next 12 years aligns with the broader trend of continuing the current Energiewende model. This boost will facilitate the next government’s ability to finance projects related to the energy transition. As with planned investments in transport, digital, and education infrastructure, it remains unclear how future governments will allocate the new funds. These resources may be used to (co-)finance projects aimed at expanding electricity and district heating networks, constructing new dispatchable power plants (mainly gas-fired), and developing hydrogen infrastructure, including storage facilities. They could also support various decarbonisation measures in the industrial sector (such as contracts for difference); heating and district heating (for example, thermal retrofitting of buildings and replacing heat sources with low-emission alternatives); and transport (promoting e-mobility and expanding public transport).

Economic consequences

The fiscal package is expected to have a positive impact on the German economy, although its full effect on the pace of economic growth will only become apparent in 2028-29, primarily due to procedural and logistical factors. According to projections by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin),[23] the special fund will raise Germany’s GDP by 1% in 2026 and by an average of 2% annually from 2027, compared with a scenario in which the package is not implemented. The public investment multiplier for the fund is estimated at two, meaning that GDP is projected to increase by twice the amount of investment spending during the period analysed. This will be driven primarily by increased demand for services, especially in the construction sector, leading to higher private investment and consumption. By contrast, increased defence spending is expected to have only a modest impact on GDP growth, as this sector plays a relatively minor role in the German economy. The value added by Germany’s defence industry accounts for less than 1% of GDP.

Moreover, forecasts suggest that the package will have a limited long-term impact on price growth, owing to underutilised production capacity in many industrial sectors, such as machinery manufacturing. Taking into account the European Central Bank’s response and the increase in interest rates, inflation is expected to rise by 0.5 percentage points annually following the introduction of the infrastructure fund.

Rising public debt and interest payments are often cited as potential risks to the German economy. According to the German Economic Institute (IW Köln), the nominal value of public debt will rise to €2.2 trillion over the 12-year lifespan of the fund (excluding increased defence spending enabled by the relaxation of the debt brake). This would raise the level of public debt to 85% of GDP by 2037, up from 63% in 2025, while the annual deficit of central and local government institutions is expected to reach around 3.3% of GDP. According to the Federal Court of Auditors, by the end of the fund’s implementation period, annual interest payments could rise by an additional €37 billion. For comparison, €34 billion was allocated to interest payments in 2024, accounting for 7.3% of total budget expenditure. There is a risk that the ratio of interest payments to tax revenues could double to 17% by 2037, generating significant pressure for fiscal consolidation. This makes it essential that the funds are genuinely directed towards investment rather than inflationary consumption.

The fund’s compatibility with the rules of the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact remains in question. The European Commission is considering allowing defence spending of up to 1.5% of GDP per year, under the ReArm Europe package, to be excluded from the budget deficit limit, which would keep Germany within the threshold. However, the future level of public debt, expected to significantly exceed the 60% of GDP ceiling, would present a problem. This would compel the German government to enter into negotiations with the Commission regarding acceptable levels of investment expenditure. Pressure from a growing number of EU member states, including Italy and France, may lead to a further relaxation of the EU’s fiscal rules. Under the new regulations adopted on 30 April 2024, investment is treated in the same manner as consumption. The substantial investment needs of EU member states could result in the introduction of a relevant clause.

Capital markets responded to the announcement of increased public spending with a rise in the yield on 10-year German bonds from 2.6% to 2.9%. Yields on French (3.6%) and Italian (4.0%) bonds also rose, reflecting growing uncertainty among investors. Despite this, German shares gained, and the euro strengthened against the dollar, indicating a moderate economic recovery. These developments coincided with an increase in the US ‘fear index’ following President Trump’s announcement of new tariffs. This may suggest that the impact of Germany’s fiscal plans on European markets has been overstated. Stimulating domestic demand through the fiscal package could help cushion the effects of the US administration’s trade policy. However, volatility in global markets is generating significant uncertainty and making it difficult to forecast the trajectory of both the German and wider European economies.

[1] A. Kozaczyńska, ‘The debt brake: Germany in a crisis of uncertainty’, OSW Commentary, no. 642, OSW, 28 January 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[2] ‘Gesetz zur Änderung des Grundgesetzes (Artikel 109, 115 und 143h)’, Bundesgesetzblatt Teil I, no. 94, Bonn, 24 March 2025, recht.bund.de.

[3] See J. Gotkowska, J. Tarociński, ‘NATO after Madrid: how much deterrence and defence on the eastern flank?’, OSW Commentary, no. 462, 5.07.2025, osw.waw.pl.

[4] Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2024), NATO, 12 June 2024, p. 7, nato.int.

[5] ‘Deutsche Verteidigungsausgaben: Intransparente Planung’, Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft, 20 August 2024, iwd.de.

[6] M. Gebauer, P.-A. Krüger, ‘So will die Bundeswehr jetzt die vielen Milliarden ausgeben’, Spiegel Online, 21 March 2025, spiegel.de.

[7] G. Heiming, ‘Einigung über die Finanzierung der Bundeswehr’, Europäische Sicherheit & Technik, 5 March 2025, esut.de.

[8] Unterrichtung durch die Wehrbeauftragte, Jahresbericht 2024 (66. Bericht), Deutscher Bundestag, Drucksache 20/15060, 11 March 2025, p. 11, bundestag.de.

[9] ‘„Wir reagieren auf die geänderte Sicherheitslage in Deutschland und Europa“’, Bundeswehr, 3 April 2024, bundeswehr.de.

[10] F. Bethmann, ‘Deutsche Rüstungsindustrie boomt’, ZDF, 20 February 2025, zdf.de.

[11] The French-German-Spanish consortium Airbus ranks 12th, with revenues of €12.9 billion. See ‘The SIPRI Top 100 arms-producing and military services companies in the world, 2023’, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, December 2024, sipri.org.

[12] L. Gibadło, P. Szymański, ‘Plans for a new model of military service in Germany’, OSW, 14 June 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[13] J.L.S. Barbin, T. Konopka, Militärische Zurückhaltung oder militärisches Engagement? Entstehung und Entwicklung der strategischen Kultur der Bundesrepublik Deutschland bis 1990 im Lichte von Archivquellen, SIRIUS – Zeitschrift für Strategische Analysen, Vol. 7, Issue 4, 2023, pp. 327–353, at: degruyterbrill.com.

[14] See a survey for ARD-DeutschlandTREND April, Infratest dimap, April 2025, infratest-dimap.de.

[15] ‘Straßenbauprojekte kosten Bund 15 Milliarden Euro mehr’, ntv, 10 September 2024, n-tv.de.

[16] T. Wüpper, ‘20 Milliarden Euro pro Jahr für Ersatz und Neubau auf der Schiene’, Stuttgarter Zeitung, 17 March 2025, stuttgarter-zeitung.de.

[17] C. Schwietering, ‘50 Milliarden Euro für notleidende Kliniken. Lauterbach krempelt medizinische Versorgung um’, Tagesspiegel, 16 March 2024, tagesspiegel.de.

[18] S. Fokken, ‘Was das Sondervermögen für Kitas, Schulen und Unis bringen könnte’, Spiegel Online, 7 March 2025, spiegel.de.

[19] F.-T. Wenzel, ‘Der Ausbau der Stromnetze kostet 650 Milliarden Euro – oder noch mehr’, Redaktionsnetzwerk Deutschland, 8 December 2024, rnd.de.

[20] Of the funds allocated for investment in the regular federal budgets, 30% went unspent in 2020, 23% in 2021, 10% in both 2022 and 2023, and 20% in 2024. Under the KTF, the unspent share amounted to 50% in 2022, 44% in 2023, and 15% in 2024. In 2024, the figure was notably reduced due to a reallocation of funds to a different purpose late in the year; otherwise, the proportion of unspent funds for the originally planned objectives would have stood at 40%.

[21] T. Hellwagner et al., ‘Wie sich eine demografisch bedingte Schrumpfung des Arbeitsmarkts noch abwenden lässt’, IAB-Forum, 21 November 2022, iab-forum.de.

[22] The Climate and Transformation Fund (German: Klima- und Transformationsfonds, KTF) is a special-purpose fund designed to finance expenditures related to the broadly defined energy transition. This includes subsidies for building insulation and heating system replacements, the development of electromobility, industrial decarbonisation, the expansion of railway infrastructure, subsidies for renewable energy, support for investments in hydrogen technologies, and even the construction of semiconductor factories. The KTF’s primary revenue sources are proceeds from sales of CO₂ emission allowances under the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) and Germany’s national emissions trading system (nEHS), which covers the transport and building sectors. The KTF’s budget for 2024–27 amounts to €212 billion.

[23] The Institute’s forecast was based on the initially announced 10-year duration of the fund, rather than the current 12-year framework.