The EU increases its agri-food imports from Ukraine: causes and reactions from Central European states

31 March 2023 saw the publication of a joint letter by the prime ministers of Poland, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia, and the president of Bulgaria, to the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen on the measures they intended to take to counteract the negative effects of the increased imports of agricultural products from Ukraine to the EU. The document highlights the unprecedented increases in imports of grain, oilseeds, fruit, dairy and honey. It also proposes measures to improve the situation of local agricultural producers, including increasing the financial support offered to them. The authors of the letter emphasise that if the market disruptions cannot be eliminated by other means, tariffs and tariff rate quotas will need to be re-introduced on imports from Ukraine (they were suspended in June 2022). On 7 April 2023, Warsaw and Kyiv reached an agreement on suspending the export of wheat, corn, sunflower seeds and rapeseed to Poland until the beginning of the new season (summer), while the transit of Ukrainian produce via Polish territory will be maintained.

The war has doubled imports of Ukrainian agri-food products to the EU. This particularly applies to grain, the import of which has risen from 7.8 million tonnes in 2021 to almost 16 million tonnes in 2022. Agri-food exports were already of key importance for Ukraine prior to the Russian invasion, and since then their role has increased further. In 2021, their value amounted to $27.7 billion and in 2022 to $23.4 billion, although at that time it already accounted for 53% of Ukraine’s total exports. Although agri-food exports fell by 15.5%, their proportion was much smaller than in other important sectors of the Ukrainian economy (for comparison, metallurgical exports dropped by 62.4% in 2022).

The characteristics of Ukraine’s agri-food exports

Before the war, two thirds of Ukraine’s exports were dispatched via ports on the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. More than 90% of agricultural produce was exported this way. The Russian invasion has resulted in some Ukrainian ports being occupied and others blocked; this triggered the need to find alternative export routes. To facilitate trade, in May 2022 the European Union established so-called ‘Solidarity Lanes’, in which Poland and Romania played key roles. The most important elements of these lanes included Ukrainian ports on the Danube and the transit operations from these ports to Romania (in 2022 the port in Constanța serviced 8.2 million tonnes of grain; this accounted for around 21% of Ukraine’s grain exports, the total of which Kyiv estimates at 38.3 million tonnes), as well as by land via Poland.

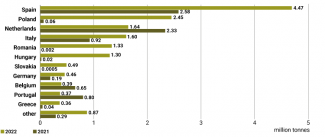

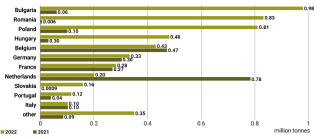

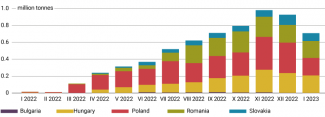

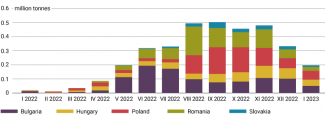

Alongside this, Ukrainian agri-food producers sought new markets for their produce, mainly focusing on Ukraine’s neighbours. Before the war, these countries had imported only insignificant amounts of cereals and oilseeds. However, in March 2022 their imports from Ukraine began to increase rapidly (see Charts 1 and 2). Despite a negative trend which started in November (possibly because of seasonal factors), the import figures remain high compared to the pre-war period.

The increase in agri-food imports from Ukraine recorded in 2022 affected specific EU member states to varying degrees (see Chart 1). While those of Ukraine’s neighbours which had not imported Ukrainian grain in previous years began to buy large amounts of it following the outbreak of the war (for example Romania recorded a more than 800-fold increase in grain imports), many EU countries which had previously bought grain from Ukraine (such as the Netherlands, Belgium and Portugal) saw their imports fall off. A similar situation regarding oilseed imports has been recorded (see Chart 2).

Chart 1. Grain imports from Ukraine to selected EU member states in 2021 and 2022

Source: Eurostat.

Chart 2. Oilseed imports from Ukraine to selected EU member states in 2021 and 2022

Source: Eurostat.

In July 2022, an agreement was signed in Istanbul establishing a so-called grain corridor, which enabled Ukraine to export agricultural produce from three of its Black Sea ports (Odesa, Chornomorsk and Pivdennyi). The first ships left these ports on 1 August. By the end of March 2023, 26.4 million tonnes of Ukrainian produce (mainly grain, oilseeds and cooking oil) had been dispatched in this way. The launch of the grain corridor has resulted in these ports regaining their dominant role in exporting agri-food products (75% in December 2022). However, this proportion was not as high as it had been before the war, most likely because the volume of exports transported by land in the following months, mainly to and via Ukraine’s EU neighbours, remained high.

Chart 3. Grain imports from Ukraine to the neighbouring EU countries between January 2022 and January 2023

Source: Eurostat.

Chart 4. Oilseed imports from Ukraine to the neighbouring EU countries between January 2022 and January 2023

Source: Eurostat.

The consequences of increased imports for Central European states

The gradual establishment of these new logistical chains in 2022 was of key importance in increasing Ukrainian grain and oilseed exports. Although the Black Sea ports have been unblocked to some degree, the lifting of tariffs and tariff rate quotas on Ukrainian produce starting from June 2022 kept profitable the export of these goods to the neighbouring countries, in particular in regions located in the vicinity of the EU border. As regards other categories of imports listed in the agreement, figures from Eurostat indicate a clear increase in cooking oil imports from Ukraine (although not as big as in the case of grain and oilseeds). Other import categories are less important because of their smaller volume.

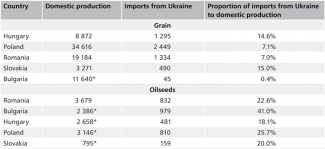

In those Central European states which have been net exporters of grain and oilseeds for many years, this was the first time when imports from Ukraine started to affect their domestic markets. In absolute numbers, Poland has become the biggest recipient of these import categories of those states. In proportion to their own production levels, the share of Ukrainian grain was the biggest in Slovakia and Hungary, and the share of Ukrainian oilseeds was the biggest in Bulgaria (see Table 1). The increase in the volume of grain imports from Ukraine and the trends recorded on the global agricultural market have contributed to a rapid decline in prices, and to the problems local farmers have faced regarding the sale of their produce from last year.

Table 1. Comparison of specific countries’ production of grain and oilseeds and their import of these products from Ukraine in 2022 (in thousands of tonnes)

* Data for 2021. Production over consecutive years has been similar, and so we have decided to use the 2021 figures in this comparison instead of 2022 figures.

Source: Eurostat (the APRO_CPSH1 data base for production, the DS-059313 data base for imports).

How specific EU member states have reacted to the increased imports from Ukraine

The losses suffered thanks to the increase in Ukrainian grain imports are an important topic in ongoing debates in Romania. The problem began to receive extensive discussion in mid-March, when it became clear that the European Commission would offer a mere €10 million to Bucharest as compensation to the farmers who have lost a major portion of their profits due to increased grain imports from Ukraine to Romania and to the grain transit via Romanian ports (while the EC pledged to offer €17 million to Bulgaria and almost €30 million to Poland). Romanian farmers estimate their losses resulting from this situation at around €200 million. Representatives of farmers’ associations have argued that the problem goes beyond the low price of the imported grain (which undermines the competitiveness of their production and forces them to reduce their prices). It also involves the fact that the launch of the transit corridor via Romania (which mainly runs to Romanian ports) has provoked an uncontrolled increase (up to five-fold) in the cost of logistical operations. There has also been a significant reduction in the availability of trucks, freight rail cars and barges. As a consequence, some Romanian farmers have been unable to sell their grain. According to the Association of Agricultural Producers from Dobrogea, since November 2022 the price of wheat has fallen 35% (from €370 to €240 per tonne). Moreover, farmers also argue that the grain exported from Ukraine to Romania fails to meet quality standards; for example, some of it is genetically modified, and some has been grown using banned pesticides, and so on.

The EC’s decision to grant just €10 million in compensation to Romania has sparked outrage among Romanian agricultural producers. They have called this sum “offensive”, and announced that they would hold protests: the first one took place on 7 April. Some agricultural associations have officially refused to accept this assistance. The situation affecting Romanian famers has also sparked political tension. As early as 23 March, the spokesman of the National Liberal Party (PNL), which is a member of the ruling coalition, expressed his party’s dissatisfaction with the amount of these funds, and stressed that the Minister of Agriculture Petre Daea (who is a member of another coalition party, the Social Democratic Party (PSD)), is responsible for negotiations with the EC. The minister has also come under criticism from other members of the PNL. President Klaus Iohannis, who is associated with this party, has joined the accusations, and on 22 March he said that “the data the ministry had presented to the EC may have been inaccurate”. Alongside this, he accused the EC of applying the accounting principles in an “ultra-bureaucratic manner” and failing to acknowledge the sacrifices being made by Romanian farmers. The opposition has expressed its criticism of the government’s actions. Dacian Cioloș, a former prime minister and current leader of the REPER opposition party, has put the blame for the insufficient compensation primarily on the minister of agriculture. According to Cioloș, the minister decided to seek assistance too late. The Eurosceptic national-conservative AUR party has criticised the EC and accused the government in Bucharest of subordinating the interests of Romanian farmers to Ukraine.

At the same time, both the PNL and the PSD are arguing that soon Romania will succeed in negotiating another instalment of EC assistance, this time bigger. These parties are competing with each other to come across as initiators of a potentially successful resolution to this problem. The agriculture minister, for his part, does not plan to resign.

Although in Bulgaria the problems with increased and duty-free import of Ukrainian agricultural produce are an important topic, until recently they had been overshadowed by the campaign for the parliamentary elections held on 2 April. They were absent from the major parties’ campaign narratives. Moreover, there are no indications that this issue might affect Bulgarian-Ukrainian relations. The provisional government and the politicians from the most important parties (excluding the pro-Russian Revival party) have avoided making statements which could be interpreted as hostile towards Ukraine. Instead, they are focused on seeking greater support from the EU and on solving the present problem at the EU level.

In late March and early April, during the week before the election, protests numbering several hundred farmers were held. They demanded that the validity of the EU regulation on duty-free import of agricultural products from Ukraine should not be extended to Bulgaria, and that the EU should earmark more funds than those initially announced (€17 million) for Romania under the compensation mechanism. During the protest, the farmers blocked the European E79 motorway, which runs through western Bulgaria, as well as several border crossing points with Romania (at Vidin, Ruse, Kardam and Silistra) which lead to Constanța. Another blockade of roads leading to that port was organised on 7 April, this time in coordination with agricultural organisations from Romania.

The protests arranged by the National Association of Grain Producers (NAZ) received support from the provisional government headed by Gailab Donev which continues to rule the country. The agriculture minister Yavor Gechev took part in one of the blockades and drove a tractor which blocked the E79 road. He called on the EU to expand the compensation mechanisms offered to farmers, and argued that from Bulgaria’s point of view the sum pledged is too small. The government has promised to actively seek to solve the problem in the forum of the European Council. The agriculture minister has maintained that “the countries located closer to Ukraine are paying a higher price for the war”, although at the same time he stated that although Sofia does support the plan to establish European corridors to transport Ukrainian grain imports, these must not be organised “at the cost of Bulgarian farmers”.

Both the government and the agricultural organisation have emphasised that the most important challenges Bulgaria is facing in connection with the import of Ukrainian grain and oilseeds concern the low purchase prices of grain and the fact that unsold domestic produce continues to be stored in warehouses. The NAZ has argued that the import of sunflower seeds is another big problem. In 2022, it amounted to more than 1.5 million tonnes, which means that it has risen more than twenty-fold compared to 2021. The farmers and the ministry have stressed that the Bulgarian market, as well as the markets of other countries of the Black Sea basin, is unable to absorb such large volumes of grain and oilseeds. As a consequence, more than 60% of Bulgaria’s annual sunflower crops remains unsold and is being stored in warehouses. Agricultural organisations estimate that at this point the situation is similar as regards almost 4 million tonnes out of more than 6.5 million tonnes of Bulgaria’s annual wheat production. The lack of demand for domestically-grown cereals has provoked concern among Bulgarian farmers regarding this year’s harvest season which will begin in June. Grain production accounts for around 10% of the country’s GDP, and generates budgetary revenues of around 9 billion lev annually (around €4.6 billion). For more than a decade, alongside Romania and Serbia, Bulgaria has been one of the regional leaders in the grain trade.

In Slovakia, the inflow of much cheaper Ukrainian grain is not among the most important topics in public debate. Although the opposition has repeatedly used pro-Russian and anti-Ukrainian rhetoric and emphasised the issue of fighting the ‘cost of living crisis’, it has not referred to the Ukrainian grain problem. Despite this, the problem continues to affect the Slovak agricultural sector, which is putting pressure on the government to launch relevant actions.

On 31 March, Prime Minister Eduard Heger stated that the so-called ‘Solidarity Lanes’ established by the EU were mainly intended to facilitate the transport of Ukrainian grain to third countries. However, due to its much lower price, some Ukrainian grain has remained in EU member states (including Slovakia); this has caused trouble for local farmers seeking to sell their produce. In this situation, the prime minister has made attempts to divert the public’s attention away from Ukraine as the alleged source of the problem, saying that the problem would not have emerged had Russia not invaded Ukraine. The topic has not been extensively discussed nationwide, although it has occasionally been mentioned, for example by Boris Kollár, the head of the We Are Family party which co-forms the government. He warned that failure to take action may “decimate Slovak farmers”. He also stressed that Brussels should earmark funds for audits to ensure that Ukrainian grain is only transported via Slovakia “to Szczecin, Gdańsk and other EU ports”, and added that similar issues have had a negative impact on the Slovak public’s solidarity with Kyiv, which should be boosted.

The ministry of agriculture and rural development has stressed that “for several months” it has emphasised the “extremely serious situation faced by the European Union border countries, linked to the import of cheap agricultural products”. This concerns both direct import from Ukraine and indirect import via the neighbouring EU member states. According to press releases published by the ministry in the second half of March, Bratislava had long called on the EC to adopt an assistance package for the countries most affected by this problem.

At the beginning of March, the ministry responded to a request by domestic flour producers and launched a series of inspections at flour mills and bakeries. The purpose of these inspections is to check whether these facilities are using flour made from Ukrainian grain in an illegal manner. For example, this involves checking their quality marks and making sure that 75% of the flour they use is made from Slovak-grown grain. The foodstuffs inspectorate, which is supervised by the ministry of agriculture, has stated that although Ukrainian-made flour and Ukrainian-grown grain are safe for human consumption, it should be recalled that Ukraine does not apply the same production standards as those applied in the EU. Slovakia’s agriculture minister Samuel Vlčan has announced that during 2022 flour mills and bakeries received the biggest subsidies in history, and he therefore expects the local food producers to show “social responsibility towards their own country”.

As regards grain, Slovakia is self-sufficient. The country’s grain harvest amounted to 4.31 million tonnes in the 2021/2 season, and its domestic consumption was 2.58 million tonnes. Each year, Slovakia exports around 40% of its grain production. Its main export partners include the Czech Republic, Austria and Germany, and its main competitors in this export category are Hungary and Romania.

In Hungary, the issue of Ukrainian grain is mainly raised by agricultural organisations, while the government has focused on accusing the European Commission of showing an inadequate response to this crisis. Although relations between Hungary and Ukraine have cooled down due to disputes over the Hungarian minority in Zakarpattia and Budapest’s stance on the war, so far the grain issue has not been used to criticise Kyiv. The government has also emphasised the joint stance adopted by the region’s states, as well as the leadership shown by Poland, which enables it to refute the accusations of a crisis in regional cooperation.

In 2022, Hungary’s grain production was exceptionally low (down 36% compared to 2021) because of a severe drought. According to figures compiled by the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, by October 2022 Hungary had imported more than 1 million tonnes of grain and oilseeds from Ukraine; for comparison, in previous years the volume had been 50,000–60,000 tonnes. The unprecedented amount of Ukrainian grain transported to Hungary has resulted in a surplus in Hungarian silos and destabilised the grain market, it has contributed to a considerable fall in the price of this commodity.

In mid-February, the Hungarian agriculture ministry accused Brussels of “being nothing more than a passive observer” to how Ukrainian-grown grain bound for North Africa and the Middle East gets stuck in Europe, resulting in serious market disruptions. István Nagy is one of five regional agriculture ministers who have asked the EC to launch anti-dumping measures intended to stabilise the situation on the local agricultural markets.

The critical discourse from the government and the agricultural sector focuses on doubts regarding the amount of grain imported from Ukraine, its quality and its potential health hazards (in the context of Ukraine using chemicals which are banned in the EU). According to a press release published by the agriculture ministry, an inspection of the food chain safety of agricultural products imported from Ukraine is ongoing. As part of this inspection, 156 companies have so far been audited, although the results have not yet been published. UBM, one of Hungary’s leading grain traders, has announced that regardless of the inspection, all the products unloaded will be tested for compliance with animal feed safety regulations and the principles of good manufacturing practice (GMP). The tests will be carried out by an independent entity accredited by the London-based Grain and Feed Trade Association (GAFTA).

A joint statement by the Association of Hungarian Farmers and Farming Co-operatives (MAGOSZ) and the Hungarian Chamber of Agriculture (NAK) published in February 2023 indicates that a “critical situation” has emerged on the Hungarian agricultural market due to the unwise decisions Brussels has taken. These organisations suggest that the standards applied to imported agri-food products should be raised significantly (for example, Ukrainian exporters should be required to prove that their products have been produced using pesticides allowed in the EU).

Ukraine’s prospects in the context of agricultural production

In 2022, Ukraine’s agricultural production was almost 40% down on 2021, mainly because of the Russian invasion. The decrease was particularly evident as regards various cereals (mainly corn and wheat), but was less prominent in the oilseed segment.

Chart 5. Comparison of production levels of the main types of cereals and oilseeds in 2021 and 2022

Source: Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine, State Statistics Committee of Ukraine.

The forecasts for 2023 suggest exports of agricultural products will fall further as a result of reduced production. As regards grain, production is estimated to decrease by around 15%, down to 46 million tonnes. In 2023, the total area under cultivation will likely shrink by around 7 million hectares (24%) compared to 2021, from 29 million to 22 million hectares. This results from some regions of Ukraine being occupied and some fields mined, which prevents farmers from carrying out their work. It seems that this factor will contribute to a drop in agricultural exports from Ukraine to the neighbouring countries. Other such factors include the re-introduction of tariffs and tariff rate quotas which the Central European leaders have proposed in their joint letter, and the agreement reached on 7 April between Warsaw and Kyiv regarding the halt in Ukraine’s export of some types of cereals to Poland.

Another potential problem is that Russia may break off the grain corridor agreement. It seems unlikely because Moscow has already prolonged the agreement twice, although should this happen, pressure on the land border between Ukraine and its neighbours will once again increase.

Sławomir Matuszak, Kamil Całus, Krzysztof Dębiec, Ilona Gizińska, Łukasz Kobeszko, co-operation: Tadeusz Iwański, Andrzej Sadecki