Poisoned gifts: humanitarian and development aid in Russia’s foreign policy

![Ил-76 МЧС России RIA Novosti archive, image #980006 / Alexey Kudenko / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [cropped]](/sites/default/files/styles/max_325x325/public/okladki/RIAN_archive_980006_Russian_humanitarian_aid_delivered_to_Turkey.png?itok=zw9oKdxK)

As the strategic rivalry between Russia and the Western world has intensified, Moscow has increasingly instrumentalised the humanitarian aid it provides in response to crises and disasters as well as its official development assistance (financial support granted by state institutions for long-term socio-economic development). Ultimately, it has turned both into a direct extension of its foreign policy, detached from the humanitarian principles that traditionally underpin aid activities.

The Kremlin actively uses these instruments to consolidate its strategic influence, thereby supporting the safeguarding of its interests, promoting its ideological agenda among the countries of the Global South, and countering the Western presence in developing nations. Russian humanitarian and development aid is therefore subordinated to Moscow’s ongoing political needs and assumes a de facto offensive character. Consequently, there are even cases when it harms recipients by exacerbating instability and worsening the very problems it purports to address.

Aid in the service of the Kremlin: the actors and their activity

In the Cold War era, the Soviet Union used humanitarian and development aid for countries of the so-called Third World (those not aligned with either the USSR and its satellite states or the Western bloc led by the United States) as a tool for achieving its objectives on the international stage.

In the 1990s, due to economic difficulties and a temporary reorientation of strategic priorities, the Russian Federation itself became a recipient of foreign aid and significantly reduced its use of this instrument towards developing countries. However, as it gradually regained its international standing and its relations with the West deteriorated, Russia increasingly returned to the use of aid as a foreign policy tool. This shift was reflected in successive editions of the Concept of the Russian Federation’s Humanitarian Policy Abroad (2007, 2014, 2023) as well as the Concept of the State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Sphere of International Development Assistance, adopted in the same years.

Viewing American and European aid programmes as manifestations of aggressive Western expansion,[1] the Kremlin – according to its own perception – responds by using humanitarian and development assistance as a foreign policy tool. This aid functions as a complement to its diplomatic, economic, military and informational-propaganda measures.

The latest version of the Russian Federation’s Humanitarian Policy Concept includes explicit references to the confrontational paradigm of international relations as represented by Moscow. The document speaks of an intensifying ‘struggle for cultural influence’, a ‘crisis of the existing international order’, and threats stemming from globalisation processes or attempts to discredit the idea of the Russkiy Mir (Russian World) by replacing it with ‘pseudo-values’.[2] The response to these challenges sees the application of a humanitarian policy defined more broadly than in the West (it has been expanded to include elements of cultural, scientific, and sports diplomacy etc.) and aimed at promoting Russia’s image and strengthening its influence through the use of soft power instruments.

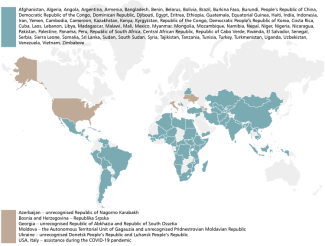

The Kremlin operates in the humanitarian and development spheres primarily in two regions: in the countries of the former USSR that it considers a priority (including para-states under its patronage), and across the Global South (Africa and the Middle East, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean). Additionally, a third area of focus includes countries with historical ties to Russia, such as Serbia and Mongolia. Moscow draws on the legacy of the Cold War era, such as positive memories of the Soviet Union and loans which it previously granted (see below). The vast majority of the recipients of Russian aid are either among the Russian Federation’s few allies or countries that maintain a benevolent neutrality towards it.

Map. States that received Russian humanitarian aid in 2020–2025

Source: author’s own analysis.

Russia does not have a centralised agency specialising in humanitarian and development assistance. Instead, it prefers to distribute aid through a broad network of entities directly or indirectly subordinate to Moscow.[3] The involvement of non-governmental organisations was minimal even before the final dismantling of Russian civil society structures, which coincided with the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[4]

The group of state actors involved in this aid includes: the parliament, various ministries (e.g. those responsible for emergency situations, foreign affairs, finance, agriculture, health, defence, etc.), and government agencies (primarily Rossotrudnichestvo, but also Rospotrebnadzor, Rosrezerv, and others). It also encompasses state-owned corporations (such as Rostec, Rosatom, and Rosoboronexport), sovereign wealth funds (notably the Russian Direct Investment Fund – RDIF), regional authorities, diplomatic missions, and cultural institutions (e.g. so-called Russian Houses, which carry out propaganda-related tasks)[5].

Entities informally linked to the Kremlin include the Russian Orthodox Church (e.g. through the Patriarchal Exarchate of Africa), private companies (such as Uralchem, Rusal, and Lukoil), formally non-governmental organisations (such as the Russian Humanitarian Mission or the Akhmat Kadyrov Foundation, which is controlled by the leader of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov), and media outlets such as the African Initiative website, serving as a propaganda arm of the Africa Corps, which is subordinated to the Russian Ministry of Defence.[6]

In its humanitarian and development activities, Russia also cooperates with UN agencies (in 2024 it ranked 11th in terms of financial contributions to the organisation’s budget) such as the World Food Programme (WFP), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). This cooperation extends to the World Bank and institutions outside the UN system, such as the New Development Bank (established by the BRICS countries, Russia holds approximately 20% of shares), and the Eurasian Development Bank (created by the Eurasian Economic Union, Russia held 45% of shares in 2023). These institutions challenge the current global financial architecture and were founded as alternatives to Western-led international integration frameworks.

Due to the large number of actors involved, as well as the incomplete and often non-transparent nature of the data, it is impossible to estimate – even approximately – the total value of Russian humanitarian aid.[7] However, it is most likely several orders of magnitude lower than the assistance provided by Western countries.

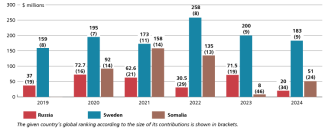

One illustrative example is Russia’s annual financial contributions to the UN World Food Programme (WFP). Russia donates significantly less than countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, the European Commission, or various Western European nations. At times Moscow’s contributions to the WFP are even lower than those made by some of the programme’s beneficiary countries.[8]

Chart 1. The contributions of Russia, Sweden and Somalia to the UN World Food Programme in 2019–2024

Source: World Food Programme.

Russian humanitarian aid is largely one-dimensional and symbolic, focusing more on immediate impact than on long-term engagement. The bulk of this aid consists of in-kind donations (such as food, medicines, and medical equipment), which contrasts with current global trends, where donors increasingly provide financial resources that offer recipients greater effectiveness and flexibility in their response efforts.[9] The humanitarian activities of Russian state-owned corporations and private companies in countries where they invest sometimes equate to the bribery of local decision-makers and elites, disguised as corporate social responsibility (CSR). For example, in 2011, the CEO of Norilsk Nickel presented then-President of South Africa Jacob Zuma with a mobile medical laboratory for the town of Nkandla, his hometown. Similarly, after South Africa’s Constitutional Court 2017 annulment of a previously signed intergovernmental agreement – tainted by clear signs of corruption – that would have allowed Rosatom to construct nuclear reactors, the Russian state-owned company shifted its engagement towards initiatives such as women’s health projects.

The total value of official development assistance (ODA) provided by the Kremlin is also unknown. In 2023, Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs estimated it at around $1 billion annually (by comparison, Poland allocated $2.6 billion in the same year). According to the most recent available OECD data, in 2019 Russia’s ODA amounted to approximately $1.2 billion, over half of which was directed through bilateral agreements. The main beneficiaries were countries with strong ties to Moscow: Cuba, Kyrgyzstan, North Korea, Syria, Armenia and Tajikistan. However, the value of Russian development assistance has likely declined in recent years. According to the OECD, in 2023 Russia was involved in 72 projects, down from 152 two years earlier. Its contribution to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) also dropped significantly – from around $16 million in 2019 to just $0.2 million in 2024.

Financial tools: debt relief and new loans

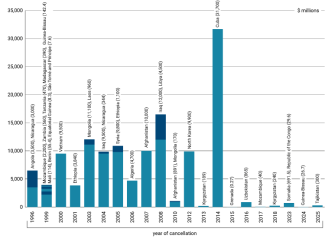

The practice of foreign debt cancellation by Moscow – one of the clearest examples of the instrumentalisation of aid – constitutes the bulk of Russia’s official development assistance. In 2019, cancelled debts accounted for over 60% of the total value. Most of the obligations which Global South countries owe to Russia date back to the Cold War era. In the early 1990s, the debt developing countries owed to Russia was estimated at approximately $110–120 billion.

The Kremlin pursues a policy of forgiving Soviet-era debts owed by countries it considers friendly, with political gain as the primary motivation. Given the minimal likelihood of recovering these debts, the policy does not represent a significant financial burden. In 2024, the Russian budget was expected to lose approximately 50 billion roubles (approximately $540 million) due to unpaid intergovernmental loans and accrued interest – relatively minor in comparison to projected federal revenues of approximately 37 trillion roubles (approximately $400 billion).[10]

Moscow also seeks to convert forgiven debts into economic benefits gained from the debtor country (such as arms purchases, granting Russian companies access to natural resources, and entry into local markets). For example, in exchange for writing off $4.7 billion of debt in 2006, Algeria signed contracts for the purchase of Russian military equipment worth $7.5 billion. Similarly, in 2008, after the Kremlin cancelled $4.5 billion in Libyan debt, Libya committed to buying arms from Russia valued at $4.6 billion.

Significantly smaller portions of the freed-up funds are allocated to humanitarian purposes. In 2014, Russia and Mozambique agreed that the remaining portion of the country’s debt – $144 million – would be used for development projects. Three years later, $40 million of that amount was allocated to fund school feeding programmes in Mozambique through the WFP. Similar agreements were concluded between 2011 and 2016 with Ethiopia, Madagascar, Tanzania and Zambia, though there is a lack of publicly available information on how the resources released under these arrangements were ultimately allocated.

Chart 2. Selected debts cancelled by the Russian Federation in 1996–2025

Source: author’s own analysis.

In recent years, the scale and pace of debt relief have declined. According to the latest statements from Russian officials, approximately $20 billion in debt has been written off for African countries since the collapse of the USSR. However, this same figure had already been cited as early as 2012, suggesting a stagnation in further debt forgiveness.[11]

On the other hand, Russia is intensifying its lending activity. In October 2024, the Russian authorities announced plans to provide loans totalling 1.6 trillion roubles (approximately $20 billion) to other states between 2025 and 2027. According to the latest available World Bank data (2022), the debt owed to Moscow by 37 countries reached approximately $29 billion – the highest level since 1999. In addition to Belarus, which regularly receives debt repayment deferrals and energy subsidies from Russia, the largest debts are held by Bangladesh, India, Egypt and Vietnam. It is therefore plausible that the Kremlin will in the near future step up its use of debt forgiveness as a political instrument. Notably, Rosatom is currently implementing nuclear energy projects in both Bangladesh and Egypt, funded through loans extended by the Russian Federation.

Offensive humanitarianism: the goals and mechanisms of action

By treating humanitarian and development policy as an extension of its foreign policy, Moscow seeks to secure its own narrow interests and disseminate its propaganda narrative – primarily across the Global South. Presenting its assistance within the framework of a struggle against a unipolar world order (implicitly: one favouring the West) and ‘neocolonial practices’, Russia simultaneously discredits Western support for developing countries and complicates its distribution. The Kremlin’s aggressive actions in this domain destabilise humanitarian conditions and generate serious risks to health, food security and broader human safety.

During the civil war in Syria, Russia provided military support to the regime of Bashar al-Assad, operating in the humanitarian sphere independently of, and even in competition with, UN-coordinated frameworks. It consistently obstructed cross-border aid initiatives aimed at areas of the country not controlled by government forces.[12] In 2019, at the UN Security Council, with support from China, Russia blocked further deliveries through Jordan and Iraq, and in 2023 it did the same for deliveries via Turkey. In a similar move, in November 2024, citing Sudan’s sovereignty, Moscow vetoed a Security Council resolution that called on the warring parties in the ongoing internal conflict (at one point, the Kremlin simultaneously supported both sides) to cease hostilities, protect civilian infrastructure, and ensure the delivery of humanitarian aid.[13]

Humanitarian and development aid provided by the Kremlin can serve as a smokescreen when conducting hybrid operations. In 2022, Rossotrudnichestvo – an entity subordinate to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and formally the closest equivalent to a foreign aid agency – was placed on the EU sanctions list due to its role in the invasion of Ukraine and occupation of its territory. Similarly, in early 2025, the Azerbaijani government decided to close the Russian House in Baku, which operates as part of Rossotrudnichestvo, reportedly due to its involvement in espionage activities.

Moscow also uses aid activities as instruments of pressure and control over neighbouring countries, particularly by supporting para-states located within the territories of former Soviet republics. In doing so, it entrenches the dependence of separatist republics whilst also gaining additional leverage to exert political influence over the states to which these entities belong in de jure terms. For instance, as many as 43 out of its 113 development projects in 2022–2023 were implemented in Abkhazia and South Ossetia (Russia has recognised their independence since the 2008 war with Georgia).[14]

The promotion of the Russian language and education in Russian is a key objective for the Kremlin. Moscow pursues these goals through initiatives such as free language courses (e.g. offered by Russian Houses), the establishment of branch campuses of Russian universities abroad, and the funding of scholarships for foreign students at Russian institutions. In 2024, over 130,000 foreign students went to study in Russia (mainly from the Central Asian countries and China), of whom 30,000 were granted tuition-free education. Notably, ten current world leaders (including the presidents of Angola, Namibia and Ghana) were educated in Russia or the former USSR.

The Russian Federation’s humanitarian and development activities also serve to mitigate reputational damage caused by the Kremlin’s expansionist foreign policy. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine significantly impacted global food security, and Moscow’s withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Initiative (which had enabled Kyiv to safely export agricultural produce by sea) further worsened the situation, sparking discontent among African countries.[15] In response, Moscow pledged to donate between 25,000 and 50,000 tonnes of grain each to Burkina Faso, Eritrea, Mali, Somalia, the Central African Republic and Zimbabwe, along with covering the cost of its transportation.

Russia has even exploited the economic sanctions imposed on it by the West in order to obtain propaganda gains from providing humanitarian aid. Following EU sanctions in 2022, the Latvian authorities blocked a shipment of approximately 200,000 tonnes of Russian fertilisers in the port of Riga (a total of around 260,000 tonnes were halted across the EU in the year the invasion began). The owner of the cargo, Uralchem Group, decided to donate it free of charge to countries of the Global South under the auspices of the World Food Programme (WFP). Between March 2023 and December 2024, a total of 190,000 tonnes of fertilisers were delivered to Malawi, Kenya, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Burkina Faso and Sri Lanka. The operation was accompanied by a propaganda campaign[16] and public accusations against the West. The Kremlin blamed Western countries for hypocrisy, deliberately obstructing humanitarian deliveries, and causing harm to the Global South through sanctions against Moscow,[17] despite the fact that the EU, to Ukraine’s dismay, relaxed restrictions on the export of Russian fertilisers.[18]

On the other hand, Russia’s ‘vaccine diplomacy’ during the COVID-19 pandemic ultimately ended in failure. In August 2020, Russia became the first country in the world to register a COVID-19 vaccine – Sputnik V. Although the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF), responsible for its production and promotion, launched an aggressive campaign bordering on marketing and propaganda, concerns over the transparency of clinical trials prevented the vaccine from being approved by either the World Health Organization (WHO) or the European Medicines Agency (EMA), damaging Sputnik V’s credibility. Nor was the vaccine authorised for use in China and South Africa, while in Brazil, following the emergence of controversy, its use was permitted only in a limited capacity. Moreover, costing $20 for two doses, Sputnik V was significantly more expensive than its Western counterparts.

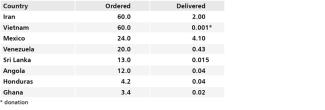

Sputnik V was approved for use in over 70 countries – including, against EMA recommendations, in Hungary and Slovakia – and its production outside Russia was launched in 13 countries (with agreements signed in 23). However, Moscow significantly overestimated its production and distribution capabilities. Although commercial contracts were signed for approximately 800 million doses of the vaccine, by mid-2022 only just over 100 million had been delivered. In the same period, the EU supplied 2.2 billion doses, China over 1 billion, and the United States more than 700 million. Russia (which did not take part in COVAX, the international vaccine distribution initiative for developing countries) donated only 1.5 million doses of Sputnik V to 19 countries, whereas the United States donated 542 million doses to 117 countries, the European Union 475 million to 104, and China 130 million to 95.[19]

Delays in deliveries led to tensions between the RDIF and its clients, particularly in Latin America. Argentina threatened to terminate its contract, while Guatemala withdrew from the agreement altogether.

Table 1. Examples of limitations in the deliveries of Sputnik V in mid-2021 (millions of doses)

* donation

Source: author’s own analysis.

The Kremlin attributed the failure of its vaccine diplomacy to anti-Russian propaganda and Western pressure on the countries of the Global South.[20] In reality, however, it exposed the fundamental weaknesses of Moscow’s humanitarian policy. Short-term actions and a focus on engaging (often pro-Russian) elites – while neglecting cooperation with non-governmental organisations and rejecting collaboration with Western countries in international formats – proved ineffective. Corruption scandals surrounding the distribution of Russian vaccines in several African countries further highlighted the lack of transparency in the Kremlin’s humanitarian operations.[21] In April 2025, media reports emerged alleging that in 2022, Kirill Dmitriev, head of the Russian Direct Investment Fund (and Vladimir Putin’s point of contact with the Trump administration on plans for economic cooperation), had requested a two-month extension of the expiration date for 6 million doses of the Sputnik Light vaccine in order to distribute them as humanitarian aid to Africa.[22]

To cover up the revealed shortcomings in its humanitarian and development assistance, the Kremlin organises disinformation campaigns targeting the West. Its efforts are aimed at undermining trust in medical initiatives funded by the United States and European nations and are particularly dangerous to public health in developing countries. For example, General Igor Kirillov, commander of the Radiological, Chemical and Biological Defence Forces (killed in an attack in December 2024), spread claims that the US was conducting military biological experiments in the Global South and considering the artificial release of the Ebola virus in Central Africa. These narratives were then amplified by the Russian propaganda apparatus.[23] Meanwhile, the African Initiative, through local bloggers, conducted a social media campaign aimed at discrediting British malaria vaccines.[24]

Moscow’s focus on its rivalry with the West not only significantly diminishes the quality of its humanitarian assistance, but may also destabilise the humanitarian conditions in developing countries and exacerbate existing problems. The severity of the future negative consequences of Russia’s activities will therefore be directly proportional to the intensity of its confrontation with the United States and European countries.

[1] Ю. Саямов, ‘Иностранная помощь как инструмент внешней политики’, Международная жизнь, no. 12, 2023, interaffairs.ru.

[2] ‘Концепция гуманитарной политики Российской Федерации за рубежом’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 14 September 2022, mid.ru.

[3] J. Robinson, ‘Russian Foreign Humanitarian Assistance. Identifying Trends Using 15 Years of Open-Source Data’, Marine Corps University Press, 13 April 2022, usmcu.edu.

[4] ‘Russia’s humanitarian aid policy’, European Parliament, May 2016, europarl.europa.eu.

[5] I.U. Klyszcz, ‘Rossotrudnichestvo in Africa: Propaganda and Soft Power’, EU vs Disinfo, 22 October 2024, euvsdisinfo.eu.

[6] See M. Bartosiewicz, P. Żochowski, ‘The Wagner forces under a new flag: Russia’s Africa Corps in Burkina Faso’, OSW, 31 January 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[7] Ю.К. Зайцев, А.Ю. Кнобель, ‘Российская гуманитарная помощь в 2024 году’, Институт экономики и политики имени Е.Т. Гайдара, 24 November 2024, iep.ru.

[8] Contributions to WFP in 2024, World Food Programme, wfp.org.

[9] M.T. Page, P. Stronski, ‘How Russia’s Hollow Humanitarianism Hurt Its Vaccine Diplomacy in Africa’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 28 April 2022, carnegieendowment.org.

[10] ‘Путин разрешил «дружественным» странам не возвращать России еще $600 млн долгов’, The Moscow Times, 29 July 2024, moscowtimes.ru.

[11] К. Солянская, ‘Подарок для Африки’, Газета.Ru, 18 October 2012, gazeta.ru.

[12] J. Robinson, ‘Exploring Russia’s Views on Humanitarian Aid in Syria’, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 4 January 2023, washingtoninstitute.org.

[13] ‘Russian Federation Vetoes Security Council Resolution Aimed at Strengthening Measures to Protect Civilians, Increase Humanitarian Aid Access in Sudan’, United Nations, 18 November 2024, press.un.org.

[14] I.U. Klyszcz, ‘Russia’s Self-Serving Aid Policy: Influence, Opacity, and Propaganda’, International Centre for Defence and Security, 6 March 2025, icds.ee.

[15] M. Bartosiewicz, ‘Mutual disappointment: the Russia-Africa summit’, OSW, 2 August 2023, osw.waw.pl.

[16] J. Surtees, ‘Growing foothold: how Russia donates fertiliser to deepen African alliances’, The Guardian, 13 March 2023, theguardian.com.

[17] ‘О безвозмездной передаче российских удобрений беднейшим странам’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 22 October 2023, mid.ru.

[18] J. Barigazzi, B. Brzeziński, B. Moens, S. Savage, ‘EU agrees to ease Russia fertilizer curbs after row, angering Ukraine’, Politico, 15 December 2022, politico.eu.

[19] J. Borrell, ‘Vaccinating the world: between promises and realities’, European External Action Service, 19 June 2022, eeas.europa.eu.

[20] ‘Vaccine Diplomacy vs Vaccine Hypocrisy’, Embassy of the Russian Federation in South Africa, oldrussianembassyza.mid.ru.

[21] M.T. Page, P. Stronski, ‘How Russia’s Hollow Humanitarianism Hurt Its Vaccine Diplomacy in Africa’, op. cit.

[22] J. Barnes, J. Rushton, ‘Putin’s top Ukraine negotiator plotted to send expired Covid vaccines to Africa’, The Telegraph, 27 April 2025, telegraph.co.uk, after: webarchive.org.

[23] ‘What Has Russia’s Late General Kirillov Said About West's Biological Activities in Africa?’, Sputnik Africa, 17 December 2024, en.sputniknews.africa.

[24] A. Blomfield, ‘How Russian interference threatens to derail malaria vaccines in Africa’, The Telegraph, 3 November 2024, telegraph.co.uk.