Elections for the chosen few? Romania nears the end of its presidential campaign

On 4 May, the first round of the presidential election will be held in Romania. This will be the country’s second attempt in six months to elect a head of state. The previous vote, held at the end of 2024, culminated in scandal. On 6 December – just two days before the planned second round – it was annulled by a highly controversial ruling of the Constitutional Court. The decision, which sparked criticism both within Romania and internationally, found that Călin Georgescu – the far-right nationalist and pro-Russian frontrunner in the first round – had violated the principle of equal opportunity for candidates by manipulating social media algorithms. A similar argument was later cited by the Central Electoral Bureau (CEB) on 9 March, when it refused to register Georgescu for the re-run of the presidential race.

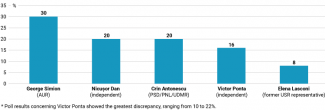

Of the eleven registered candidates, the clear frontrunner is George Simion, leader of the radical national-conservative Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR), who is backed by Georgescu. Polls suggest Simion could secure around 30% of the vote. He is likely to face one of the two main rivals in the second round: either Crin Antonescu, representing the governing coalition, or Nicuşor Dan, the independent mayor of Bucharest – both polling at around 20%. Former Prime Minister Victor Ponta, polling between 10% and 20%, stands only a slim chance of reaching the run-off. While the final outcome is unlikely to significantly alter Romania’s foreign policy, it may deepen the long-standing crisis affecting the country’s political elite.

A re-run overshadowed by controversy…

The May presidential election will take place under the shadow of one of the most serious political and constitutional crises in post-communist Romania’s history. The turmoil began in late November and early December last year with the unexpected electoral success of Călin Georgescu. Previously little known, the far-right politician had been polling at around 5% just a week before the first round, yet managed to secure as much as 23% of the vote. Both the government and Georgescu’s political opponents quickly began to suspect manipulation or external interference – primarily from the Kremlin.

This hypothesis gained further traction following the declassification of intelligence reports on 4 December – just ahead of the planned second round – by order of President Klaus Iohannis. Romanian intelligence concluded that Georgescu’s electoral breakthrough was the result of a complex and large-scale social media campaign, primarily on TikTok. According to the reports, the scale of the operation suggested the involvement of an unnamed ‘state actor’. The manipulation techniques used in the campaign reportedly resembled those previously employed by Russia against Ukraine.[1]

Two days after the publication of the intelligence reports, the Constitutional Court – despite having previously validated the result of the first round – decided to annul the entire election and order a re-run. The judges based their decision partly on the declassified reports, concluding that Georgescu had engaged in manipulation by employing ‘opaque and election law-violating digital technologies and artificial intelligence’ in his campaign. This, they argued, breached the principle of equal opportunity among presidential candidates.[2] They also highlighted the lack of transparency in the financing of Georgescu’s campaign, which the candidate himself claimed had not involved any expenditure.[3]

The annulment met with widespread domestic criticism. Many commentators and opposition politicians regarded it as a politically motivated attempt by the ruling mainstream political forces – comprising the centre-left Social Democratic Party (PSD) and the centre-right National Liberal Party (PNL) – to eliminate an ‘outsider’ candidate. The public response was largely one of confusion and disapproval. By the end of December last year, nearly two-thirds of Romanians considered the Constitutional Court’s decision to be wrong.[4]

The Romanian government was also criticised by the international community. On 14 February, during a speech at the Munich Security Conference, US Vice President J.D. Vance openly condemned the annulment of the election in Romania, arguing that the decision was based on ‘flimsy suspicions of an intelligence agency’. The American official also expressed scepticism about the state of Romanian democracy, suggesting that it ‘wasn’t very strong’ if Russia could ‘destroy it with a few hundred thousand dollars of digital advertising’ on social media.[5] Earlier, on 27 January, the Venice Commission had also voiced its concerns over the Constitutional Court’s ruling.[6] In its report, the commission stated that such decisions must not rely solely on classified intelligence, as this fails to ensure the necessary level of transparency.

…and without the leading candidate

In the months following the Constitutional Court’s ruling, doubts continued to grow over the legitimacy of the annulment of the elections. The investigation into campaign-related manipulation, launched in late 2024, did produce evidence of Georgescu’s ties to domestic far-right circles and to a controversial group of mercenaries led by Horațiu Potra – his personal bodyguard. However, despite sustained efforts, the Romanian state failed to credibly demonstrate any links between Georgescu and the Kremlin, or to prove that his campaign had been financed by Russian entities. This reinforced his image as an anti-establishment figure and cast him as a ‘martyr’ persecuted by the political elite. Consequently, Georgescu’s popularity nearly doubled – rising from 23% in November 2024 to between 40% and 45% in January and February this year.[7]

Given his strong support, the candidate had no intention of withdrawing from the race. According to his campaign team, he submitted his application for registration with the Central Electoral Bureau (CEB) on 26 February. That same day, however, he was detained by police and taken to the prosecutor’s office, which formally charged him with multiple offences. Chief among them were participation in an anti-constitutional conspiracy and membership of an organisation with antisemitic leanings.[8] Although the authorities did not place Georgescu in pre-trial detention, they imposed a travel ban and restricted his access to social media platforms.

The politician eventually submitted his candidacy a few days later, but the CEB rejected it.[9] Notably, the justification for the decision did not refer to the charges brought against him by the prosecutor’s office or to allegations of ties with Russia. Instead, the bureau cited the Constitutional Court’s ruling of 6 December. It argued that an individual such as Georgescu, who fails to uphold the principle of equal opportunity in presidential elections does not respect democratic norms or the constitution. These, it stressed, are requirements for the head of state and, by extension, for any presidential candidate.[10]

Georgescu’s anointed successor

According to public opinion polls, a significant portion of the electorate disenfranchised by Georgescu’s exclusion has shifted its support to George Simion, who currently enjoys around 30% backing. In the first round of the 2024 election, Simion had finished in fourth place with under 14% of the vote – well below the projected 20%. Following Georgescu’s unexpected success, he swiftly declared his full support for the far-right candidate. Once it became clear that a repeat election would be held, the AUR leader announced he would not run, stating he did not wish to compete against a like-minded candidate with strong public support.

At the same time, AUR – claiming that the cancellation of the election amounted to a de facto coup – began staging regular rallies in support of Georgescu under the slogan ‘Restore the Run-off'. This move appeared to stem less from ideological conviction than from political calculation. Simion, who also employs anti-establishment rhetoric, positioned himself as a defender of Romanian voters whose ‘right to vote had been taken away’, while portraying himself as a selfless figure uninterested in power. In reality, he likely anticipated that the Central Electoral Bureau would bar Georgescu from running and hoped to inherit a share of his support base by casting himself as the successor of his political narrative. To reinforce this image, Simion declared – following Georgescu’s disqualification – that he had no intention of running for president. He later reversed this position following a conversation with Georgescu, which served as a form of political ‘anointment’.[11]

Who is Simion?

The leader of AUR and current frontrunner in the May presidential election is a politician with distinctly nationalist views. George Simion has been active in Romania’s public life since the 2010s. In 2011, he founded Acțiunea 2012 (Action 2012), a socio-political movement consisting of over 30 organisations advocating for the unification of neighbouring Moldova with Romania. In 2019, Simion established the Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR), and in 2020 he succeeded in bringing the party into parliament with 9% of the vote. Four years later, AUR doubled its representation, securing over 18%. Once sceptical or even openly hostile toward the European Union, Simion now supports Romania’s continued membership, emphasising his ambition for the country to claim its ‘rightful place’ within the EU.[12]

Since January 2025, he has also held the position of vice-president within the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), one of the major groups in the European Parliament. He has cited Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni as a political role model and considers her party, Brothers of Italy, a template for his own movement.[13] Simion is also firmly pro-NATO and pro-American, and has openly expressed admiration for Donald Trump’s political camp. He frequently references statements from Washington that criticise the annulment of the Romanian elections, including remarks by J.D. Vance and Elon Musk.

Mainstream media and the political establishment have long accused Simion of harbouring ties to the Kremlin. This is one of the reasons why he has been declared persona non grata in both Ukraine and Moldova. These allegations, however, have not been substantiated. At the same time, Simion – like a significant share of the Romanian population – remains sceptical of Ukraine and of Bucharest’s policy of supporting Kyiv. Beyond alleged pro-Russian leanings, he has also faced accusations of sympathising with the Iron Guard and the Legion of Michael the Archangel – interwar and World War II-era Romanian fascist and antisemitic organisations.[14]

Other key candidates

The main rivals to Simion are Crin Antonescu, representing the ruling coalition of the Social Democratic Party (PSD), the National Liberal Party (PNL), and the Hungarian minority party UDMR; and Nicuşor Dan, the independent mayor of Bucharest, who is backed by the Save Romania Union (USR), a party he formerly belonged to.

According to available polls, Antonescu can expect to receive approximately 20–25% of the vote. The ruling coalition selected him as their joint candidate shortly after the annulment of the 2024 elections. Unlike the November race, in which each of the three parties fielded their own candidate, the coalition chose to unite behind a single figure in response to the surge in Georgescu’s popularity and, more broadly, the rise of anti-establishment movements. The governing coalition decided to run a single candidate, recognising that only a united front could realistically secure the presidency. However, due to internal rivalries between leading figures within PSD and PNL, none of the current leaders or high-profile politicians from these parties were seen as viable consensus candidates. Instead, the coalition turned to Antonescu – a once-prominent figure who had been absent from public life for a decade, and whose political career reached its peak in the early 2010s. In 2009, he became leader of the PNL and ran for president, placing third with 20% of the vote. In 2011, he was among the founders of the Social Liberal Union (USL), a political alliance that brought together PNL and the post-communist PSD for three years. During this period, the bloc made an unsuccessful attempt to impeach centre-right President Traian Băsescu.

As a result, Antonescu has become the symbolic representative of the alliance between Romania’s two dominant ruling parties. This not only lends him credibility as the governing coalition’s candidate but also constitutes a significant liability in terms of public perception. The Romanian electorate is increasingly fatigued by the political forces that have held power since the 1990s. The fact that the PSD–PNL coalition was re-formed in 2021 and extended after last year’s elections has been widely perceived not only as a further consolidation of the old elite but also, by many of the parties’ own supporters, as a betrayal. Except for the 2011–2013 period when they temporarily governed together, PSD and PNL had long been principal rivals. Their renewed alliance has pushed segments of the electorate towards more radical and extreme parties and candidates who offer a promise of disrupting the entrenched political establishment.

Nicuşor Dan, who polls at around 20%, has served as mayor of Bucharest since 2020 and was re-elected last year. He has been active in public life since 2006, when he founded Save Bucharest Association – one of Romania’s first urban civic movements. The group advocated for preserving the capital’s architectural heritage and was engaged in combating corruption in local government. In 2015, this movement evolved into a political platform known as the Save Bucharest Union, which was soon transformed into a national political party – Save Romania Union (USR).

Dan’s political narrative consistently calls for the replacement of Romania’s ruling elite – or rather building a new one. He advocates for transparency, anti-corruption efforts, the protection of civil rights and the strengthening of the rule of law. Unambiguously pro-European and pro-Western, he distances himself from traditional ideological divides, avoiding affiliation with either the conservative or progressive camps. In 2017, a debate within USR regarding the party’s stance on abortion – where Dan advocated for ideological neutrality while others promoted a liberal position – prompted him to leave the party.[15] As a result, although Dan, like Simion, seems to belong within the broader anti-establishment camp, he represents a far more moderate alternative. Crucially, Dan is a strong supporter of enhancing European integration.

Though Dan is formally running as an independent, he is backed by several smaller political groups. Chief among them are Renewing Romania’s European Project (REPER), led by former Prime Minister Dacian Cioloș and composed largely of former USR members, and the People’s Movement Party (PMP), associated with former President Traian Băsescu. In April, USR’s leadership also formally endorsed Dan, despite previously fielding its own candidate – party leader Elena Lasconi.[16] The shift came in response to a sharp decline in Lasconi’s popularity. Although she placed second with 19% in the first round of the annulled 2024 election, April polls suggest she now commands no more than 8% support.[17]

The last of the major contenders is Victor Ponta, former Prime Minister of Romania and long-time leader of the Social Democratic Party (PSD), who is currently polling at 10–20%. Ponta seeks to capitalise on the growing public disillusionment with the political establishment and on prevailing conservative sentiments. Despite his roots in the political elite, he consistently attempts to position himself as an anti-establishment candidate, espousing views that closely mirror those of Donald Trump. Ponta frequently emphasises his strong ties with figures from the MAGA (Make America Great Again) movement and is a regular participant in events organised by its affiliates.

Forecast

There is little doubt that the presidential election will be decided in the second round. It is widely considered almost certain that George Simion will be one of the two final candidates. In addition to his projected 30% domestic support, he is expected to receive a significant share of the Romanian diaspora’s vote.[18] In the first round of the annulled election, 16% of all votes cast for Georgescu – who politically endorsed Simion – came from abroad. Simion’s likely opponent in the run-off will be either Crin Antonescu or Nicuşor Dan. Victor Ponta’s chances of advancing to the second round appear slim, particularly after a controversial remark he made during the final month of the campaign. On 9 April, he claimed that during the 2014 floods, while serving as prime minister, he had ordered the deliberate flooding of several Romanian villages to protect Belgrade, and that he was later rewarded with Serbian citizenship.[19]

In the anticipated second round, the key challenge for Simion’s rivals will be mobilising a broader electorate. Antonescu, backed by the governing parties with their extensive local structures, has a clear advantage over Dan in this regard. However, facing the coalition’s candidate would also be the most favourable scenario for the leader of AUR, as it would allow him to draw on his anti-establishment narrative and exploit public resentment towards the political elite blamed for annulling the 2024 election. Conversely, Dan may find it challenging to attract Antonescu’s supporters. A significant portion of the PSD’s traditional electorate – particularly from rural and economically disadvantaged areas – holds conservative and often nationalist views. These voters are unlikely to support the Bucharest mayor, who is perceived as a liberal and a representative of the urban intellectual elite.

Regardless of the final outcome of the May election, the events of the past six months will have far-reaching and systemic consequences for Romania’s political landscape. The annulment of the presidential election, followed by Georgescu’s exclusion from the re-run – without a convincing justification for either action – has further eroded already low levels of public trust in the authorities and state institutions. These institutions, primarily the Constitutional Court, face growing accusations not only of politicisation and acting in the interests of the ruling parties, but also of inefficiency and incompetence. Even among Georgescu’s opponents – those who consider the repetition of the election and his disqualification legitimate – there is widespread criticism of the state apparatus, and in particular the intelligence services, for allowing the crisis to unfold in the first place and for their role in the ensuing chaos. Together, these developments have deepened long-standing public fatigue and disillusionment with the political establishment. In the near future, this may lead to a significant reshaping of Romania’s power structures and could ultimately contribute to the removal of the current ruling elite from power.

Chart. Polling support for the leading candidates in Romania’s presidential election (4 May 2025)

Source: Averaged results of polls conducted between 3 and 17 April 2025 by seven public opinion research institutes in Romania.

[1] The declassified intelligence reports are available on the official website of the President of Romania.

[2] ‘Hotărârea nr.32 din 6 decembrie 2024 privind anularea procesului electoral cu privire la alegerea Președintelui României din anul 2024’, Constitutional Court of Romania, ccr.ro.

[3] For more on the annulment of the elections in Romania, see: K. Całus, ‘Romania; Constitutional Court annuls the presidential election’, OSW, 9 December 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[4] M. Roman, ‘62% dintre respondenți consideră că anularea alegerilor prezidențiale a fost o decizie proastă – sondaj IRES’, G4Media.ro, 28 December 2024.

[5] ‘Vice President JD Vance Delivers Remarks at the Munich Security Conference’, White House, 14 February 2025, youtube.com.

[6] Urgent report on the cancellation of election results by constitutional courts, Venice Commission, 27 January 2025, venice.coe.int.

[7] ‘Călin Georgescu are un scor de 45%. Este sondajul de ultimă oră făcut de specialiști’, Realitatea.net, 6 March 2025.

[8] ‘Călin Georgescu, pus sub control judiciar, după 5 ore de audieri. Un magistrat este cercetat alături de politician. Acuzațiile aduse’, Digi24.ro, 26 February 2025.

[9] K. Całus, ‘Romania: new presidential election without Georgescu’, OSW, 18 March 2025, osw.waw.pl.

[10] Georgescu contested the Central Electoral Bureau’s decision at the Constitutional Court, but in its ruling on 11 March this year, the court chose to dismiss the complaint.

[11] Georgescu de facto endorsed two politicians: George Simion and Anamaria Gavrilă, the leader of the pro-Georgescu Party of Young People (POT). However, the two agreed not to compete against each other. Instead, they decided that the candidate with lower support in a specially commissioned confidential poll would withdraw in favour of the other. As a result, on 19 March, Gavrilă announced her withdrawal from the presidential race.

[12] ‘Apărătorii Patriei Române în Europa. Noi, românii, suntem APĂRĂTORII SECULARI AI EUROPEI’, George Simion, 2 March 2024, georgesimion.ro.

[13] A. Draghici, ‘George Simion, discurs alături de Giorgia Meloni pe care a numit-o 'leoaica Europei': Modelul nostru politic nu este Ursula von der Leyen’, Stiripesurse.ro, 17 December 2023.

[14] For more on Simion and AUR, see: K. Całus, ‘A shift further to the right. Radical parties are gaining popularity in Romania’, OSW Commentary, no. 592, 29 April 2024, osw.waw.pl.

[15] At the time, Dan stated that he wanted ’USR to be a party where both conservatives and progressives can find their place. If we can’t maintain that, I’m leaving’.

[16] D.L. Bularca, S. Pricop, ‘Liderii USR anunță retragerea sprijinului acordat lui Lasconi în alegeri: Doar Nicușor Dan poate împiedica tur 2 Simion-Ponta. Din păcate, ea vrea să continue’, HotNews.ro, 9 April 2025.

[17] T. Marinescu, ‘SONDAJ Crin Antonescu urcă o poziție în clasament. Singurul candidat în fața căruia Simion ar lua mai multe voturi’, Adevarul.ro, 15 April 2025.

[18] Unlike the mainstream parties, AUR has for years been highly effective in reaching this segment of the population – primarily through the internet. Moreover, a significant portion of Romania’s emigrants believe that the country’s economic mismanagement by successive elites forced them to leave. AUR also appeals to the diaspora through its rhetoric centred on national dignity, which resonates with many emigrants who often feel undervalued or overlooked by the political establishment at home.

[19] D. Vulcan, ‘Victor Ponta spune că a primit cetățenia sârbă după ce a salvat Belgradul, în 2014, prin decizia de a inunda sate românești’, Europa Liberă România, 10 April 2025, romania.europalibera.org.