Hungary’s ongoing demographic decline: an increase in birth rates is the only hope

Hungary’s population of 9.6 million has declined by nearly 8% since the political transition. In 2023, the country recorded the third-largest annual population decline among EU member states. This ongoing depopulation, which has persisted since the mid-1980s, is accompanied by demographic trends typical of contemporary Western societies: a low fertility rate leading to fewer births, and an ageing population. While Hungary is not alone in facing demographic challenges, what sets it apart is the distinctly pronatalist stance of its government. Since 2010, successive cabinets under Viktor Orbán have intensified family policy efforts aimed at boosting fertility rates, while rejecting migration as a tool to improve the country’s demographic outlook.

In the previous decade, Hungary succeeded in increasing its fertility rate, which rose from 1.23 in 2011 to 1.61 in 2021. However, results from the most recent census indicate that despite this improvement, Hungary experienced a record population decline of 334,000 individuals between 2011 and 2022. Since 2022, Hungarian birth rates have once again been falling, with the fertility rate dropping to 1.38 by 2024. Depopulation is now progressing at its fastest rate to date. Although the government continues to allocate substantial funding to pronatalist policies, the decline in births appears to be driven primarily by macroeconomic factors and prevailing public sentiment.

A record depopulation

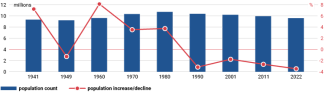

According to the results of the 2022 census, Hungary’s population stands at 9.6 million, reflecting a 3.4% decrease (334,000 individuals) over the past decade. This marks the largest decline ever recorded between two census cycles, which typically occur every 10 years (see Chart 1). The previous record drop occurred in the 1980s, when the population decreased by 3.1%.[1] This means the most recent figures surpass even the demographic decline of late Kádár-era Hungary, a period known for the rise of consumerist attitudes symbolised by the popular phrase ‘car or child’ (kicsi vagy kocsi in Hungarian). The latest data from 2023 confirms the continuation of this downward trend, with the population recorded at 9.59 million. Projections based on a trend-based scenario – assuming a continuation of current demographic patterns – indicate that Hungary’s population could fall to 8.5 million by 2050, amounting to a 13% decrease over the next three decades.[2]

Chart 1. Change in Hungary’s population between censuses conducted from 1941 to 2022

Source: Hungarian Central Statistical Office.

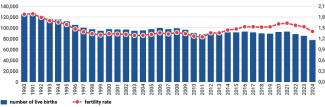

Hungary’s population size is primarily affected by a negative rate of natural increase – that is, when the number of deaths exceeds the number of live births. The country’s positive migration balance is not sufficient to offset this demographic loss. According to the prevailing demographic doctrine, equilibrium in this regard – meaning the number of births equalling the number of deaths – which ensures so-called simple generational replacement, requires a fertility rate of 2.1 (expressed as the ratio of live births to the population of women aged 15–44). In Hungary, this rate fell to a critically low level of 1.23 in 2011. A period of gradual improvement followed, with the rate rising to 1.61 by 2021.

Since 2022, Hungary has experienced a renewed decline in its fertility rate, dropping to 1.38 in 2024, a 9.1% decrease compared to 2023. Interestingly, in the two extreme years in terms of fertility – 2011 and 2022 – nearly the same number of children were born. This paradox results from a demographic shift: in 2011, more women gave birth to approximately the same total number of children as fewer women did in 2022, indicating a growing tendency among Hungarian women to have larger families. In 2024, only 77,500 children were born – the lowest figure since records began – representing a year-on-year decline of more than 7,000.

Chart 2. Trends in the number of births and fertility rate, 1990–2023

Source: Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH).

Although the decline in Hungary’s population in recent years has also been influenced by an increased number of deaths (particularly high during the COVID-19 pandemic), as well as periods of negative net migration, the most recent data primarily indicate a breakdown in the previously positive trend of rising fertility. Boosting the fertility rate has remained a top political priority for Fidesz, the party in power since 2010, which has committed substantial budgetary resources to an expansive set of family policy programmes. The government cannot be denied a degree of success in this area, particularly its achievement in reversing the downward fertility trend between 2012 and 2021, during which the fertility rate remained stable or increased.

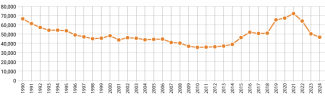

The latest demographic data also show a rise in the number of marriages in Hungary. The number of marriages reached a historic low in 2010, with only 35,000 marriages registered. Since then, a steady increase was observed, culminating in a sharp surge from 2019 onward – by 2021, over 72,000 marriages had been recorded, representing an increase of more than 50% compared to a decade earlier. The Hungarian government heavily promoted this success in recent years. However, the sudden drop to 64,000 marriages in 2022 and a further decline to just 50,000 in 2024 pose a narrative challenge for the authorities.

Chart 3. Number of marriages in Hungary, 1990–2024

Source: Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH).

The upward trend in marriages recorded from 2011 to 2021 was clearly correlated with formal requirements linking access to family benefits to marital status. These benefits included tax relief and preferential mortgage loans for first-time homebuyers, even for childless couples, provided they declared the intention to have children. This ‘marriage boom’ was largely driven by the fact that in earlier years, cohabitation had been the predominant form of partnership among Hungarians. Consequently, there was an increase in the number of couples willing to marry for purely pragmatic reasons, primarily to qualify for state support. Over time, however, this surplus of eligible couples was exhausted, and for this reason, the positive trend in the number of marriages did not prove sustainable.

The persistence of positive demographic trends in previous years (particularly the rise in fertility rates, but also the increase in marriages) served as tangible evidence for the Hungarian government of the effectiveness of its conservative family policy. These developments allowed it to showcase Hungary’s success on the international stage. During the period of demographic prosperity between 2010 and 2020, Hungary recorded the second-largest increase in the fertility rate among 52 OECD countries – a 21% rise, second only to Latvia.[3] However, the collapse of this positive trend in the past two to three years, despite no major changes in government policy, suggests that the declining willingness of Hungarians to have children is likely rooted in factors beyond pronatalist policy alone. These broader influences include GDP levels, consumer inflation, and the purchasing power of wages.

Three decades of pro-natalist policies: different concepts, one goal

Unlike other post-socialist countries in the region, where systemic family policy solutions were introduced gradually, Hungary entered its new political era drawing heavily on the legacy of the extensive Kádár-era welfare system. Generous state transfers have continued to characterise Hungarian family policy. Although these benefits were partially curtailed in the mid-1990s by the liberal and socialist governments through a programme of budget cuts (the so-called Bokros Package), the first Orbán government (1998–2002) reinstated a more generous social policy. Family benefits were increased by 20%, and a thirteenth salary was introduced.[4] As early as 2000, Fidesz leader Viktor Orbán declared that the standard for Hungarian families should be “three rooms, three children, and four wheels” (három szoba, három gyerek, négy kerék), a phrase that later became a campaign slogan.

The left-wing governments that ruled Hungary from 2002 to 2010 initially continued the previous administration’s family policy efforts, including further increases in benefits (for instance, the childbirth allowance was raised to 225% of the minimum wage[5]). However, in the following years, their focus shifted more towards promoting the labour market participation of mothers, expanding the number of childcare and educational institutions, and combating child poverty (including among Roma children, as the Roma minority accounts for approximately 6–7% of the country’s population). Due to the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, which hit Hungary particularly hard, the real value of family allowances – including the key GYES benefit (see Appendix) – declined by more than 15%.[6]

After returning to power in 2010, the conservative Fidesz–KDNP coalition made achieving a fertility rate of 2.1 by 2030 one of its key political goals. The Orbán government reinstated the two-year GYED parental leave and the three-year GYES leave, both of which had previously been reduced by the socialist administration as part of its crisis response. At the same time, it limited the ability of mothers receiving benefits to engage in full-time employment. New measures included tax relief for large families, introduced despite the existence of a flat income tax system in Hungary. Since 2016, the government has also offered preferential loans to couples who declare their intention to have children (babaváró hitel), as well as to families with more than two children who wish to purchase their first home or build a house through the CSOK programme (családi otthonteremtési kedvezmény). This programme also provides safeguards against job loss.

Since the transition period, Hungarian family policy has been marked by relatively generous benefits. However, left-wing governments generally favoured universal benefits, while Fidesz increasingly tied support to the labour market participation of mothers – and later, fathers as well. The last four terms of Viktor Orbán’s government have firmly established a shift toward this latter model, though not without adjustments over the past 15 years. The expansion of financial benefits to include tax and loan incentives, together with the integration of family support into housing policy, constitutes the most significant change. These measures have made middle-class families the primary beneficiaries of Hungary’s current family policy, as they are better positioned to access broader forms of support beyond basic allowances — including financial transfers that increase in line with income levels. By contrast, the poorest families, including many of Roma origin, benefit far less from the system.

Family policy instruments in Hungary have evolved over the years, but they have consistently remained focused on increasing the birth rate, with relatively high levels of financial resources allocated to their implementation. Family policy has been the main priority for the Hungarian authorities, and consequently, as early as the beginning of the 21st century, Hungary became the European leader in public spending on families relative to GDP.[7] According to OECD data for 2019, Hungary devoted 3.1% of its GDP to family-oriented measures, including 0.7% in the form of tax relief. However, the structure of this spending differs significantly from that in other countries. In Hungary, three-quarters of these expenditures are cash transfers (such as benefits and tax credits), while only one-quarter goes to services like nurseries and kindergartens. This contrasts with the Nordic countries, which maintain similarly high levels of overall family spending but prioritise services over cash support. According to the Hungarian government’s own statements, current spending on family policy amounts to as much as 5% of GDP. This figure likely relies on a different methodology than that used in the OECD’s comparative statistics.[8]

Demographic policy in Fidesz’s ideology

Demographic trends in Hungary – such as negative natural population growth leading to depopulation and an ageing population – do not differ significantly from those recorded in other Western countries. These trends are largely linked to transformations in lifestyle patterns typical of modern societies. Similar dynamics are evident across other Central European countries, where fertility rates also remain well below the threshold required for simple generational replacement. In 2023, the fertility rate was 1.16 in Poland, 1.45 in the Czech Republic, 1.49 in Slovakia, and 1.51 in Hungary — all substantially below the replacement level.

A distinctive feature of the Hungarian debate on demographic change is the historically rooted fear of ‘death of nation’ (nemzethalál)[9]. This collective anxiety stems from the so-called Herderian prophecy[10] formulated at the end of the 18th century, in which the German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder suggested — more as a marginal note than a definitive forecast — that the Hungarians, as a small nation wedged between Slavs, Germans, and Romanians, might not survive in the long term. Herder’s observation had a profound impact on Hungarian intellectual life during the era of national self-determination and continues to shape the collective imagination today. This sentiment is particularly resonant in light of the historical trauma of the Treaty of Trianon, which sealed the loss of two-thirds of Hungary’s pre-World War I territory.[11]

In the rhetoric of Fidesz – the ruling party in Hungary for four consecutive terms – family and children are portrayed as more than just elements of a traditional conservative worldview. The 2011 Hungarian Constitution explicitly frames the family as an institution whose support is a fundamental responsibility of the state, vital for the ‘survival of the nation’.[12] This framing gained even greater prominence following the 2015–2016 migration crisis, when demographic themes became central to the government’s narrative. As Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has emphasised:

‘We have demographic problems, but we don’t need migrants – we need Hungarian children. That’s why we oppose migration and support families’[13]. For Fidesz, boosting birth rates is seen not only as a means of ensuring the nation’s survival but also as a principal safeguard against ‘ideological threats from a liberal, multicultural West’. In this narrative, stimulating fertility among native Hungarians is presented as the only legitimate alternative to accepting non-European migrants, who, according to the party, endanger the ‘cultural integrity’ of European nations.

Over the past 15 years, Hungary’s pronatalist policy has evolved into an ideological ‘export product’ for the country. Combating Europe’s demographic crisis has been one of the central themes of Hungary’s presidencies of the Council of the European Union — both in 2011 and again in 2024. Since 2015, Hungary has hosted the biennial Budapest Demographic Summit, an international forum focused on demographic issues. The summit’s host until recently was President Katalin Novák (2022–2024), who had previously served as Minister for Family Affairs. The perceived successes of Hungary’s family policy – reflected in the temporary improvement in fertility statistics – have gained recognition among international conservative circles, particularly within Donald Trump’s political camp, with which Fidesz is ideologically aligned. One of the most vocal promoters of the Hungarian model is Tucker Carlson, the controversial former Fox News presenter.[14] Hungary’s demographic approach has also become a topic of discussion among Republican elites at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC), which has, for the past three years, held an edition of the conference in Budapest.

The politicisation of migration processes

Although the Hungarian authorities are firmly opposed to immigration, this does not mean that incoming populations are entirely unwelcome. This particularly applies to ethnic Hungarians living abroad. Since its first term in office, the Fidesz government has pursued a policy toward Hungarian minorities in neighbouring countries, officially aimed at strengthening those communities. Paradoxically, however, this policy has also led to measures that make it easier for ethnic Hungarians to return to the homeland. A turning point in this regard was the 2001 law concerning Hungarians living abroad. The introduction of the Hungarian Card can be seen as part of a broader strategy to mitigate domestic demographic challenges. This objective was further reinforced by 2007 legislation permitting residence for third-country nationals, as well as by the introduction of simplified naturalisation and dual citizenship in 2011.

Between 1990 and 2007, more than two-thirds of Hungary’s incoming population came from neighbouring countries with significant Hungarian minorities (notably Romania, Ukraine, Serbia, and Slovakia). The largest group arrived from Romania.[15] The 2011 legislation led to a sharp increase in the number of Hungarian citizens born outside the country, a trend recorded until 2016 (prior to 2012, only 2,000–3,000 such individuals were registered annually, but by 2015 this figure had risen to nearly 18,000). In recent years, the figure has stabilised at under 10,000 annually. It is estimated that without the influx of ethnic Hungarians from neighbouring states over the past few decades, Hungary’s current population would be lower by approximately 1 million individuals.[16] This migration has largely offset the country’s negative demographic trends – since the 1990s, more people have moved to Hungary than have left it.

The number of Hungarian citizens emigrating over the years shows a gradual increase in outflows after 2007, with notable peaks in 2011 and again in 2014–2015. Following these waves, a decline in emigration has been recorded since 2016. Between 2000 and 2023, the net international migration rate – measured per 1,000 inhabitants – was negative in only three years: 2013, 2014, and 2016, when more people left Hungary than entered. However, it is important to note that national statistics on Hungarian emigration tend to be significantly lower than so-called mirror statistics from receiving countries. According to Eurostat data, approximately 370,000 Hungarians were living in the European Union as of the end of 2021 — a figure that has remained relatively stable for several years. The largest Hungarian population resides in Germany (approximately 190,000), having overtaken the United Kingdom following Brexit. In Austria, the Hungarian population reached approximately 100,000 in 2021.

Chart 4. Hungary’s migration balance, 2000–2023

Source: Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH).

Hungary’s sharply anti-immigration rhetoric emerged during the height of the 2015 migration crisis, when around 400,000 refugees passed through the country within just a few weeks — the vast majority continuing on to wealthier Western European nations. In response to this influx, the Hungarian government sought to position itself as a defender of the Schengen Area. Soon after, it decided to construct a 175-kilometre fence along the border with Serbia. This barrier became a symbol of the government’s resistance to accepting ‘illegal’ immigrants and to complying with EU asylum legislation. Consequently, in June 2024, the European Court of Justice imposed a fine of €200 million on Hungary, along with a daily penalty of €1 million for each day of delay in aligning its laws with EU regulations. The Hungarian authorities have regularly launched anti-immigration billboard campaigns and frequently suggest in media messaging that immigration is directly linked to terrorism, crime, and rising unemployment.

Despite the government’s strong anti-immigration rhetoric, Hungary is increasingly becoming a destination country for immigration. This shift is driven by a growing labour shortage, which in recent years has become an urgent issue for many sectors of the Hungarian economy – particularly construction and transport – and a serious constraint on industrial growth. According to forecasts, the Hungarian labour market will require an additional 300,000 workers by 2035. Data from the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH) shows that in 2024, nearly 251,000 foreign nationals were residing in Hungary. Of these, 139,000 came from Europe and 92,000 from Asia. In 2023, the numbers stood at 144,000 and 65,000, respectively, indicating a sharp increase in immigration from Asia alongside a decline in arrivals from Europe. The law on the temporary stay of third-country nationals, passed in December 2023, regulates the inflow of migrants from 15 non-EU countries. While their arrival will not resolve Hungary’s depopulation problem, it will help address the labour shortage – for example, by supplying workers to new Chinese factories producing lithium-ion batteries and electric vehicles. The introduction of such measures points to a pragmatic turn in government policy, even if it contradicts earlier narratives – in this case, the rejection of migration from different cultural backgrounds.

Outlook: Is this the right path?

The attractiveness of a country’s parental benefits system is relative and should be assessed in the context of the prevailing economic situation. From the perspective of working beneficiaries, a key consideration is the cost-effectiveness of staying at home with a child – the extent to which income is replaced depends not only on the benefit amount, but also on inflation and the resulting real purchasing power. In Hungary, persistently high inflation since 2022 has reduced the real value of benefits, and housing-related programmes have become less suitable for many families in the face of ongoing economic uncertainty.

The years 2012–2019, during which Hungary maintained a stable or rising fertility rate, also coincided with a period of economic prosperity marked by growing GDP and the rapid expansion of the middle class. One economic indicator that shows a clear inverse correlation with fertility is the rate of inflation. Low inflation tends to accompany a higher fertility rate, and vice versa. In 2022 – the year when the previously positive fertility trend broke – Hungary experienced a sharp surge in inflation, reaching an average annual rate of 14%.

In addition, the authorities in Budapest are currently grappling with an economic slowdown – with technical recession occurring twice in the past two years – and a high budget deficit, projected at 5.4% of GDP for 2024. In the short term, this may compel the government to implement cuts in welfare spending. Some reductions have already been announced: the CSOK housing subsidy programme for large families will now apply only in rural areas, and the preferential loan programme for married women expecting a child has been tightened by lowering the upper age limit for eligibility from 41 to 30. From the perspective of Hungary’s overall family policy system, these are not major cuts. This suggests that neither the reversal in demographic trends nor current economic turbulence has provoked a change in the government’s strategic orientation on family policy. On the contrary – in his state of the nation address on 22 February, Prime Minister Orbán announced, as part of his election promises, lifetime income tax exemption for mothers of at least two children. With parliamentary elections scheduled for spring 2026 and the growing strength of a new opposition, the ruling party is expected to continue prioritising family support as one of its most important social welfare programmes and key tools for maintaining public support.

Chart 5. Relationship between the fertility rate and the consumer price index (CPI) 2010–2023

Source: É. Anita, ‘Sosem született még ilyen kevés magyar gyerek – ezért pukkadt ki az orbáni családpolitika’, Válasz Online, 11 November 2024, valaszonline.hu.

Due to the structure of its social welfare policy, Hungary is regarded as a country of ‘premature prosperity’ – one in which welfare services were established during a period of economic growth. Consequently, during periods of stagnation or decline, the country’s limited economic capacity becomes more evident, in turn influencing decisions regarding childbearing.[17] A similar effect occurred during the global financial crisis of 2007–2009, which not only brought Hungary to the brink of financial collapse but also had a negative impact on demographic indicators. From this perspective, the current state of the Hungarian economy, along with prevailing public sentiment, clearly does not support fertility growth. Government measures that once served as motivation to expand families have now largely lost their effectiveness.

The exhaustion of Hungary’s current family policy model in the realities of the economic crisis necessitates the search for alternative solutions. Migration could represent a remedy for the country’s ongoing population decline. However, migration from neighbouring countries with Hungarian minorities, which has long supported demographic stability, can no longer be relied upon, as its potential has largely been depleted. To address this, Budapest would need to become more open to accepting immigrants from beyond Europe. While migration from the Middle East appears unlikely due to the ideological opposition of the Hungarian authorities, the admission of contract workers from China and Southeast Asian countries (particularly the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia) is becoming an increasingly realistic option, and one Hungary is now embracing more willingly.

APPENDIX

Hungary’s family support system

An extensive system of parental leave and benefits remains the foundation of Hungary’s family policy, now accessible to both parents. Families can access three main types of support: CSED (formerly TGYAS), GYES, and GYED. The first – CSED (csecsemőgondozási díj) – is the equivalent of maternity leave. It lasts for 24 weeks, and women covered by social insurance (i.e. those who have worked for at least one year within the two years prior to giving birth) are entitled to receive 70% of their previous salary. Once maternity leave ends, one of the parents becomes eligible to apply for either GYES (gyermekgondozást segítő ellátás) or GYED (gyermekngondozási díj).

The GYES benefit is available to uninsured individuals until the child reaches the age of three (or longer in the case of multiple births or disability). It is a flat-rate allowance, amounting to 28,500 forints per month (approximately €71) per child, regardless of income. This benefit can also be claimed by the child’s grandparents when the child is between one and two years old. Parental leave and the GYED benefit, on the other hand, are intended for insured parents. Following the end of maternity leave, one of the parents is entitled to receive GYED until the child reaches the age of two. In this case, the allowance is 70% of the parent’s earnings, with a cap set at 407,000 forints gross per month (approximately €1,000).

Hungarian families also benefit from an extensive system of tax relief. Married couples filing jointly can claim a monthly tax allowance of 10,000 forints (approximately €25) for one child, 20,000 forints (approximately €50) for two children, and 33,000 forints (approximately €83) for three children. These amounts are set to increase in two stages by 2026 — to 20,000, 80,000, and 66,000 forints respectively. Mothers of four or more children are permanently exempt from paying income tax. Starting in October 2025, this exemption will also apply to mothers of three children, and from 2026, to those with two children. An interesting feature of the Hungarian system is its link between family size and retirement. Women who have raised five or more children are entitled to early retirement — up to seven years before the standard retirement age.

[1] It is worth noting that while the censuses of 1980 and 1990 were conducted at 10-year intervals, the gap between the 2011 and 2022 censuses was eleven years

[2] L. Bálint et al., ‘Population trends in Hungary in the last decade with an outlook’, Scienta et securitas, yearbook III, no. IV, 2022, p. 321.

[3] S.R. Larson, ‘Hungary: Europe’s Pro-Family Leader’, The European Conservative, 10 January 2023, europeanconservative.com.

[4] T. Inglot, D. Szikra, C. Rat, Continuity and Change in Family Policies of the New European Democracies: a Comparison of Poland, Hungary and Romania, ed. National Council of Eurasian and East European Research, Seattle 2011, p. 20.

[5] 2002. évi XXXIII. törvény a családok támogatásáról szóló 1998. évi LXXXIV. törvény módosításáról (XXXIII law of 2002 on amending the LXXXIV law of 1998 on family support).

[6] T. Inglot, D. Szikra, C. Rat, op. cit., p. 25.

[7] ‘OECD Family Database’, OECD, 19 December 2024, oecd.org.

[8] P. Szalai, K. Nagy, M.Zs. Varga, ‘Revealing the Facts: a Brief History of Family Benefits in Poland’, Hungarian Conservative, 13 April 2024, hungarianconservative.com.

[9] N.G. Miklós, ‘Bár megállítható a népességfogyás Magyarországon, Orbán célja elérhetetlen’, 24.HU, 12 September 2022.

[10] Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744–1803) was a German philosopher and writer, whose views greatly influenced the concept of nation states.

[11] A. Sadecki, The long shadow of the Treaty of Trianon. Hungary’s struggles with the past, OSW, Warszawa 2020.

[12] ‘Magyarország Alaptörvénye’ (Hungary’s constitution) [in:] Magyar Közlöny, year 2011, no. 43, p. 10658.

[13] Viktor Orbán in an interview with Kossuth Rádió, 27 January 2020.

[14] ‘Fox News praises Hungary’s family policy’, About Hungary, 18 February 2019, abouthungary.hu.

[15] I. Gödri, ‘Nemzetközi vándorlás’ [in:] Demográfiai portré 2015. Jelentés a magyar népesség helyzetéről, J. Monostori, P. Őri, Z. Spéder (ed.), Budapest 2015.

[16] T. Kopyś, ‘Upolitycznienie procesów depopulacji i migracji na Węgrzech po 1989 roku’, Politeja, no. 1(76), 2022.

[17] B. Pająk-Patkowska, K. Patkowski, ‘Węgry w latach 1990–2011. Polityczne, ekonomiczne i społeczne przyczyny kryzysu’ [in:] Środkowoeuropejskie Studia Polityczne, 2012, no. 3, p. 263–286.